Sanger’s Victory by Allan Carlson

Sanger’s Victory

How Planned Parenthood’s Founder Played the Christians—and Won

by Allan Carlson

Margaret Sanger was born in 1879 in Corning, New York, and raised in a stridently socialist, feminist, and atheist home. Her father “deplored” the Roman Catholic Church. In 1913 she journeyed to Europe to study contraceptive techniques. The following year, she launched her publication The Woman Rebel under the masthead, “No Gods, No Masters.” The same year she also popularized the phrase, “birth control.”

On July 5, 1915, Sanger gave a speech at the Fabian Society Hall in London, in which she asserted that “the basis of feminism was a woman’s right to be an unmarried mother.” She ridiculed reform efforts to support motherhood—“better baby funds, Little Mothers leagues, milk stations for babies, child nurseries for the children” and “mothers’ pensions”—as so many slaps in the face of women.

Her object, she said, was to give working women “a class independence which says to the masters, produce your own slaves—keep your religion, your ethics and your morality for yourselves.” She also threw a little popular eugenics into the speech, citing Friedrich Nietzsche’s warning that the world was becoming peopled by a ludicrous species, “a gently grunting domestic animal called man.”

But over the next few years, Sanger shifted tactics. In order to cultivate people of wealth and influence, she subdued her socialist proclivities. She focused on making birth control available, combining social action, civil disobedience, and feminism with conservative financial support. In 1917, she opened her first birth control clinic in Brooklyn. Arrested, tried, and convicted under New York’s mini-Comstock law, she spent thirty days in the Queens County Penitentiary, becoming a celebrity in the process.

Sanger also revised her case for birth control. Part of this meant perfecting her negative message. She showed a “special genius” in confronting her religious, scholarly, and political foes with the brutal realities to be found in some women’s lives. As she remarked, “How academic, how anemically intellectual and how remote from throbbing, bleeding humanity all of these prejudiced arguments sound, when one has been brought face to face with the reality of suffering.”

It also meant finding a positive vision of birth control that would break through traditionalist opposition. The Great War of 1914–1918 came to her aid. It shattered moral and religious certainties, allowing Sanger to offer instead a “new” morality attuned to the times, for “morality is nothing but the sum total, the net residuum, of social habits, the codification of customs,” she wrote.

Sanger added that when children were “conceived in love and born into an atmosphere of happiness,” parenthood was “a glorious privilege and the children will grow to resemble gods.” Now avoiding praise of unwed mothers, she instead argued that “we want mothers to be fit. We want them to conceive in joy and gladness. We want them to carry their babies during the whole nine months in a sound and healthy body and with a happy, joyous, hopeful mind.” Still using the language of eugenics, she asserted that through birth control, “mothers will bring forth, in purity and joy, a race that is morally and spiritually free.”

Choosing an Enemy

But to finally succeed, Sanger needed an enemy; the Roman Catholic Church fit the bill perfectly. Sanger correctly perceived that pre-1914 fears of Roman Catholic expansion in America would swell into a wave of anti-Catholicism after the war. The Ku Klux Klan enjoyed explosive growth after 1918, with membership climbing briefly into the millions and with “Catholic hordes” among its foes. At the level of law, the new immigration act of 1924 was, as a committee report put it, an effort “to guarantee, as best we can at this late date, racial homogeneity in the United States”; by this, the law’s architects implicitly meant white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant.

Opposition to Catholicism also suited Sanger personally. Her father had tutored her on the presumed evils and dangers of Rome. Moreover, her study of and involvement in socialist activities before the war had taught her the value of a clearly identified foe when launching a social-political movement. Already marginalized in American life, Catholics were the obvious choice. In her desire to gain a sacred canopy for birth control, she could easily play on four-century-old antipathies between Protestants and Catholics to bring the former to her side.

As historian Herschel Yates, Jr., has noted, Sanger’s “battle with the Roman Catholic Church was an ideological one.” The early Christian community, Sanger argued in Woman and the New Race (1920), was actually anti-natalist, focused on celibacy and conversion. Only later would it use the “sex force for its own interest,” to produce laymen who would sustain, financially and otherwise, a growing ecclesiastical order. While pagan Roman women had considerable freedom, she said, the Christian Church now “exhorted women to bear as many children as possible.” She added:

If Christianity turned the clock of general progress back a thousand years, it turned back the clock two thousand years for women. Its greatest outrage upon her was to forbid her to control the function of motherhood under any circumstances, thus limiting her life’s work to bringing forth and rearing children.

The Church, she went on, “has always known and feared the spiritual potentialities of woman’s freedom.” As another writer put it in an early issue of the Birth Control Review, “the [Catholic] church . . . prefers myths to facts, tradition to experience, darkness to light.” This focus on Catholicism’s reputed war on science and knowledge would later blossom into an appeal to Protestants to break ranks with Catholics, since, it was asserted, the birth control movement was only seeking what “any good Protestant” would want but was “prohibited from achieving . . . by an alien, half-Americanized Roman Catholicism.”

Clarifying the Catholic View

A clarification of the Roman Catholic position on birth control actually played into Sanger’s hands and set the stage for two decades of jousting between Sanger and her major, post-Comstock foe: Father John A. Ryan.

Among American Protestants and Catholics alike, there was relatively little public discussion of contraception between the passage of the federal Comstock law in 1873 and Comstock’s death in 1915. His resolution of this issue and his suppression of the trade in contraceptives seem to have been supported by a broad consensus of American Christians.

Sanger’s activism opened a new debate. In 1915, Fr. Ryan—a professor of social ethics at Catholic University of America and the champion of a “living family wage”—received an invitation to join the nascent Birth Control League. He responded:

I regard the practice which your organization desires to promote as immoral, degrading, and stupid. The so-called contraceptive devices are intrinsically immoral because they involve the unnatural use, the perversion of a human faculty. . . . Such conduct is quite [as] immoral as self mutilation or the practice of solitary vice.

The letter subsequently appeared in an article for Harper’s Weekly, where author Mary Alden Hopkins labeled it as the only extant evidence of contemporary American Catholic belief regarding birth control. While Fr. Ryan tried to clarify matters in a letter to the editor, the episode clearly inspired him to write a more complete account of Catholic teaching in light of new press attention in America to “birth control” and “contraception.” Addressed to his fellow priests, his essay in Ecclesiastical Review “set forth the new emphases in American Catholic Policy on birth control,” arguments that would stand unchanged for over five decades. Indeed, historian Kathleen Tobin asserts that Ryan’s essay and advocacy were the primary reasons “that the Catholic Church in America developed such a vocal stance against birth control.”

Ryan’s article declared that there “is no possibility of a legitimate difference of opinion among Catholics” regarding contraception, while acknowledging that many of the laity were “considerably tainted” by the practice. Why did the Church condemn “all positive methods of birth prevention”? It was clear that the “generative faculty” had as its “essential end the procreation of offspring.” When this faculty was so employed that the fulfillment of its purpose was impossible, “it is perverted, used unnaturally, and therefore sinfully.”

What harm was done? Ryan replied that the “moral order is violated . . . the sanctity of nature is outraged; the natural law of the human organism is transgressed.” By degrading the wife to the level of a prostitute, birth control also led to a “loss of respect toward the conjugal partner, and loss of faith in the sacredness of the nuptial bed.” As head of the Social Action Department of the National Catholic Conference, Ryan subsequently drafted a “Pastoral Letter” reiterating these arguments, which the American bishops duly sent out in 1919 to priests and the laity.

The Town Hall Incident

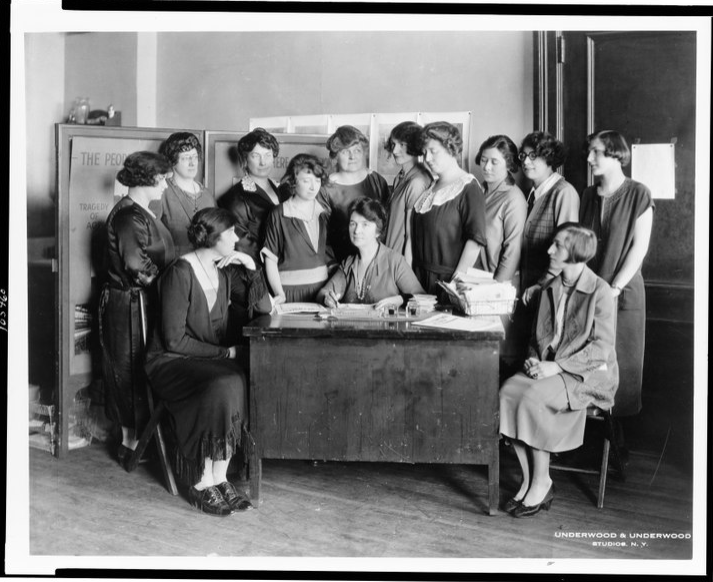

In late 1921, Sanger won a huge public relations victory over the Catholic Church in the so-called Town Hall incident. The occasion was a conference in New York City designed to launch formally the American Birth Control League. Sponsors of the session included such notables as novelist Theodore Dreiser and the English statesman Winston Churchill. Two days of organizational and medical meetings took place without incident.

Then, on a Sunday evening, a mass meeting was to be held in Town Hall on West 43rd Street. The subject was “Birth Control: Is It Moral?”

According to Sanger’s autobiographical account, when she and her colleagues pulled up to the Town Hall’s doors, they were blocked shut, and a policeman told her, “There ain’t going to be no meeting. That’s all I can say.” But with a confused crowd milling about, Sanger managed to slip inside, where she found the hall half-filled. A policeman pulled her from the stage, and then, Sanger claims, a man who identified himself as Monsignor Dineen, secretary to Archbishop Patrick Hayes, strode to the platform and told her associate Anne Kennedy, “This meeting must be closed.” When Anne asked what right the archbishop had to interfere,” Dineen allegedly replied, “He has the right.”

With the crowd shouting, “Defy them! Defy them!” the police then arrested Sanger and two other speakers. According to some accounts, the arrestees insisted on walking to the precinct station, accompanied by hundreds of their followers. Anne Kennedy brought along the reporters, completing the political theater.

A subsequent investigation determined that the police had acted responsibly, without pressure from Archbishop Hayes. However, the story quickly gained momentum as a tale of Catholic oppression of free speech. A few days later, after the New York Times published Archbishop Hayes’s Christmas letter, in which he denounced birth control, Sanger was invited to write a reply. She sharpened the argument that she would employ for the next two decades:

There is no objection to the Catholic Church inculcating its doctrines to its own people, but when it attempts to make these ideas legislative acts and enforce its opinions and code of morals upon the Protestant members of this country, then I do consider its attempt an interference with the principles of this democracy, and I have a right to protest.

Elsewhere, she crowed about the incident: “The clumsy and illegal tactics of our opponents made the whole country aware of what we were doing. . . . Thus our first national conference was crowned with triumph.”

Church Control vs. Birth Control

In vain did Catholic advocates note that as of 1921 not a single Protestant denomination or group had endorsed birth control; all remained formally opposed to the practice. In vain did they point out that existing laws against contraceptives were the uniform product of nineteenth-century Evangelical Protestant political influence.

Instead, Sanger set the new terms of debate. As she wrote in her autobiography, “Ever since the outburst of religious intolerance at Town Hall, it [has] been apparent that in the United States the Catholic hierarchy and officialdom were going to be the principal enemies of birth control.” The Town Hall incident, she went on to explain in the Birth Control Review, “has shown up the sinister control of the Roman Catholic Church, which attempts—and to a great extent succeeds—to control all questions of public and private morality in these United States.”

She continued, “All who resent this sinister Church Control of life and conduct . . . must now choose between Church Control and Birth Control.” Neutrality was not a choice. “You must make a declaration of independence, of self-reliance, or submit to the dictatorship of the Roman Catholic hierarchy . . . a dictatorship of celibates.”

In subsequent years, certain Catholic organizations would apply economic or political pressure to suppress birth control meetings. In 1922, the Knights of Columbus put pressure on the mayor of Boston to prevent a lecture by Sanger. Similar episodes occurred in Albany (1923) and Syracuse (1924). In other cities, the Knights used the threat of economic boycotts to get meeting halls closed off from birth control advocates. In Milwaukee, pressure came from the Catholic Women’s League. Sanger delighted in reporting on them, for they underscored her claims to speak for liberty in the face of “Romanist” machinations.

Whither the Protestants?

Another of Sanger’s brilliant strategies was simply to ignore Protestant writers, preachers, and churches that continued to denounce birth control. By demonizing the Catholic Church alone (although she also lashed out at Missouri Synod Lutherans) and by claiming to defend the Protestant conscience from Roman oppression, she left the impression that Protestants were on her side, in the apparent hope that this would become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Historian David Kennedy notes that the debate over birth control did grow during the 1920s, particularly among Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Methodists, Northern Baptists, and the other denominations that had formed the Federal Council of Churches of Christ (FCCC) in 1908. This debate became entwined with a broader struggle for power between theological liberals and conservatives, as the Evangelical consensus of the nineteenth century unraveled.

The church most vulnerable to doctrinal change proved to be the Episcopal Church. But that was not clear in 1908 when the Lambeth conference—an international gathering of Anglican bishops, normally held every ten years—adopted a statement labeling “self-restraint within marriage” a “man’s right,” and calling for the prohibition of all “neo-Malthusian appliances,” the prosecution of those who enabled “preventive methods,” a tighter regulation of midwives, and a national recognition of “the dignity of motherhood.” In 1920, the next (war-delayed) Lambeth conference delivered “an emphatic warning against the use of unnatural means for the avoidance of conception.” The bishops specifically condemned that teaching which “encouraged married people in the deliberate cultivation of sexual union as an end in itself.”

As early as 1916, the Moody Bible Institute’s Christian Workers Magazine began editorializing against birth control. Commenting on a sermon by A. C. Dixon, it denounced the Malthusian argument that the Great War had been caused by overpopulation, saying, “that theory is from the devil.” It also favorably described a speaker “of the Federated Catholic Societies” who traced the birth control issue back to the “detestable act” of Onan and who blamed “socialist leaders, aided by the anarchists and other neo-Malthusian ‘uplifters,’” for bringing on “the national agitation of this wickedness in the name of social betterment.” The journal positively quoted the unnamed Catholic: “If men would only read and believe the Bible, and obey God who revealed it they would find that they might in a holy and proper way multiply and replenish the earth.”

Other commentaries followed. Published by the Bible Institute of Los Angeles, The King’s Business quoted evangelist R. A. Torrey: “Be fruitful and multiply. This command has never been abrogated. One of the sins that threatens our national life today is the sin of disobedience to this command.” In 1920, the Christian Workers Magazine blasted childless marriages, arguing from the Bible that “the happiness of man and woman” was only a secondary purpose of marriage; its “prime purpose is to produce healthy children.” In Our Hope, the editors described a 1925 gathering of birth control movement leaders as one where “the scheme of limiting births was endorsed by infidels, professional men, and preachers.”

Fundamentalists Speak Out

Leading fundamentalist preachers also took on birth control. The Rev. Mark Matthews of Seattle denounced the childless home as “a menace to good government.” The “natural” home was one “filled with children. Nature demands that the home be crowned with child life.” He blamed “misguided, superficial women” for the “wicked and malicious actions” of birth prevention.

John Roach Straton of New York, sometimes labeled “The Protestant Pope” by journalists, wrote in 1920 that “we are witnessing the widest wave of immorality in the history of the human race.” He denounced the Flappers, or the “New Women”: “They wanted to be . . . men’s casual and light-hearted companions; not broad-hipped mothers of the race, but irresponsible playmates.” He blasted birth control as “artificial interference with the sources of life” and labeled the Birth Control League of New York a “chamber of horrors.”

The Rev. J. C. Masse of North Carolina dismissed birth control as “legalized concubinage.” The fundamentalist Presbyterian Clarence E. MacCartney condemned birth control as a violation of natural morality, adding: “where men are interested in the New Birth . . . they will have little time or taste to discuss Birth Control.” MacCartney was particularly incensed by emerging clerical supporters of birth prevention:

Should the recommendations of many Protestant ministers today be followed, it will come to this. . . . After a second or third child has been brought into the home . . . the Protestant minister will be summoned to strangle it, so that the firstborn will have a chance to go to college.

Billy Sunday, the greatest evangelist of the era, was a fierce foe of birth control. Perhaps influenced by his own precarious childhood, Sunday idealized the home and the place of the mother within: “It remains with womanhood today to lift our social life to a higher plane.” He scorned those “married women who shrink from maternity,” and referred to the “birth control faddists” as “the devil’s mouthpiece.” Women who used pessaries wore “the Mark of Cain.”

While anti-Catholicism grew among liberal Protestants, the fundamentalists tended to be remarkably praiseworthy of the Church of Rome. In denouncing divorce, Billy Sunday declared, “I am a Catholic” on this question. Moody Bible Institute publications regularly praised Catholic sexual ethics. And in 1929, John Roach Straton stood alongside Fr. William J. Duane, the president of Fordham University, at a rally protesting a proposed New York law to legalize the giving of birth control information to married couples. Straton congratulated the Catholic Church for its opposition to both divorce and “race suicide.”

Sanger Courts Eugenicists

The high tide of the “science of eugenics” came in 1930, precisely correlated with the first official Protestant approval of birth control. This was not a coincidence. As historian Kathleen Tobin explains, “the religious debate over birth control did not begin with the legalization of contraceptives, it began with eugenics.”

The process was complex. On the eugenics side, many prominent advocates opposed or distrusted birth control. They feared that only the better educated and “more fit” would practice contraception, leaving the “unfit” to breed. Eugenicist Henry Fairchild Osborn called birth control “fundamentally unnatural” and concluded that “on eugenic as well as on evolutionary lines I am strongly opposed to many directions which the birth control movement is taking.”

The convergence of birth control, eugenics, and Christianity followed two tracks. On the first, Margaret Sanger courted the eugenicists. In the early 1920s, birth control remained contentious and was still broadly seen as vile and immoral. In contrast, eugenics stood as a popular and seemingly obvious new science aimed at the production of healthier, stronger, and more intelligent children. Few denounced it; even leading Catholics admired the eugenicists’ elevation of marriage.

At the Second International Eugenics Conference in 1921, Sanger enthusiastically embraced eugenics, arguing that “the most urgent problem today is how to limit and discourage the overfertility of the mentally and physically defective.” She emphasized how the legalization and distribution of contraceptives would assist this goal. Indeed, early issues of the Birth Control Review featured on its masthead, “Birth Control: To Create a Race of Thoroughbreds.”

The 1921 conference also launched the American Eugenics Society (AES), which had 1,200 members by 1930. Sanger soon had an important ally in Leon F. Whitney, who served as the AES Executive Secretary. An enthusiastic supporter of Sanger, he repeatedly pushed for formal linkages between his group and the American Birth Control League.

Eugenicists Court Christians

On the second track, the eugenicists courted the Christians, with notable success. Writing in Applied Eugenics, analyst Paul Popenoe called Christianity the “natural ally of the eugenicist.” Florence Brown Sherbon declared that “one of our eugenic apostles is the preacher.” It was the “job of the preacher,” she said, “to tune the soul of man to the new universe.”

Toward that end, the AES recruited religious leaders to its Advisory Council. A prominent catch was the Rev. Harry Emerson Fosdick, the Baptist pastor of New York’s prestigious Riverside Church (his most prominent parishioners were the Rockefellers, who later became decisive advocates for birth control). Also joining the council were William Lawrence, an Episcopal bishop, and Fr. John Cooper, a professor of theology and social ethics at the Catholic University of America.

In 1925, the AES created the Committee on Cooperation with Clergymen; it quickly became the largest and best funded of its fourteen committees. Chaired by the Rev. Henry Strong Huntington, the brother of Yale geographer and eugenicist Ellsworth Huntington, the committee had 29 members by 1927, including Charles Clayton Morrison, editor of the Christian Century; Methodist Bishop Francis John McConnell; and the Rev. S. Parkes Cadman. The latter two would serve as successive presidents of the FCCC during the late 1920s. Roman Catholic members actually included Father John A. Ryan, the leading Catholic foe of birth control.

When the Christian Century listed 25 “men of prophetic vision, of pulpit power” in 1925, seven were members of the AES committee (an eighth, Newell Dwight Hillis, was also a prominent eugenicist). About 80 percent of the AES’s total budget supported this committee’s work, including funding for a highly successful, biannual Eugenics Sermon contest.

Eugenics & the Social Gospel

Liberal Christians needed little convincing, though, for eugenics played directly into the ideals of the Social Gospel, especially the post-millennial goal of creating the Kingdom of God on earth through human action and social reform. Eugenics allowed leading Protestants to reconcile their fear of being displaced by Roman Catholics with the optimism of the Social Gospel. Birth control would be their tool. While few Protestants openly called for family limitation among Roman Catholics and other “inferior” peoples, this was their implicit goal. Eugenics gave them scientific, “progressive” cover.

Christian eugenicists mobilized a battery of arguments. Some were straight out of the “hard” eugenics playbook. Writing in the Methodist Quarterly Review, C. L. Dorris charged that “too many physically, mentally, and morally defective” persons were entering society. Marriages needed to be planned for their “racial consequences.” Drawing from Havelock Ellis, Dorris concluded that since “the birth of a child is a social act,” the community can “demand that the citizen be worthy.”

However, the more powerful Protestant appeals were to eugenics as the true path to the Kingdom. The Rev. William A. Matson, a Methodist pastor in Livingston, California, wrote that “we have assumed that if we could sufficiently advance education, sanitation, and social surroundings the Kingdom of God would come.” It did not work, for “that is like trying to strengthen the pillars of society by painting them.” Only eugenics could strengthen the pillars themselves—human beings—and open the way to the Millennium.

A. G. Kellor, a lay Christian preacher and professor of sociology at Yale University, welcomed “the contraception of the present” as “the enlistment of science in the service of a higher standard of living,” and he praised “companionate marriage” as sensible.

MacArthur’s “Ideal Society”

Even bolder voices emerged. The family of Rev. Kenneth MacArthur, pastor of the Federated Church of Sterling, Massachusetts, actually won the “Fitter Family Contest—Average Family Class [four children],” held at the Eastern States Exposition in 1925 and sponsored by the AES. In a subsequent sermon, Rev. MacArthur noted that a generation of church leaders, “open-minded idealists,” have dared “to dream of a new social order, a world made up of Christ-like men and women.” He continued: “This structure of the temple of God among men must be built of the best human material.” Brashly, he declared:

Now, eugenics offers a way, consistent with Christian principles, of freeing the race in a few generations of a large proportion of the feeble-minded, the criminal, the licentious, by seeing to it by means of surgery or segregation, that persons carrying these anti-social traits shall leave behind no tainted offspring.

Both poverty and ignorance were the consequence of “low-grade human beings.” Eugenics aimed at producing “a super race” marked by intelligence, health, and good will. It also provided a synthesis of the Christian “Law of Love” with Darwin’s “Survival of the Fittest,” binding “ministry to the feeble-minded” with a plan of action that would prevent them “from pouring their corrupt currents into the race stream.”

Importantly, MacArthur also insisted that “eugenics can set the church people right on the whole question of birth control.” There “must be legalized control of the human race” before overpopulation led to war. He continued: “The church in its striving after a better world cannot afford ignorantly to condemn this powerful weapon of birth regulation which has thus far largely been an injury to the race but which has great capacities for racial improvement.”

He urged Christian philanthropists to subsidize Protestant ministers so they “could afford large families,” while introducing “birth control for less desirable stocks and segregation [in institutions] for the patently unfit.” In this way, “without any massacre or anything contrary to the love of Christ, race progress may go on to an ideal society, until we all attain to the fullness of the stature of Christ.”

“Assisting” God with Eugenics

In his popular sermon, “The Refiner’s Fire,” the Rev. Phillips Endecott Osgood of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Minneapolis cast Jesus as the ultimate eugenicist, the “Refiner” of men: “He was superlatively concerned to better the qualities of human living” and he saw children as “the near edge of the future, the beginning of the ultimate.” Marriage and childbearing should be reserved “for those who are wholesome and normal.” The unfortunate victim of a hereditary malady should deny himself parenthood and so “become a redemptive helper of the next generation.”

This meant that the Church would also “have to take its stand on the question of birth control.” He added: “In our cooperation with the Refiner’s work, we must accept heredity as our major factor.”

Another sermon published in Eugenics, this one by Edwin Bishop, pastor of Plymouth Congregational Church in Lansing, Michigan, also wove together the themes of evolution, birth control, eugenics, and the Kingdom of God. Bishop insisted that men and women were summoned to assist God in the task of transformation: “Shall we humans not realize what God is trying to do for us and how He suggests that we participate with Him in conscious evolution?” He believed that Jesus had a program “for self-fulfillment for the individual and for the race,” which could only be accomplished with “more knowledge and practice of simple eugenic laws.”

Bishop’s “practical suggestions” included the “right” of a state “to insist on sterilization” of “those notoriously unfit to marry and reproduce.” And, “as a corollary, the knowledge of birth control should be widely and freely disseminated so that among certain groups in our civilization there may be not more but fewer and better children.”

Shifting Protestant Views

Were these only peculiar or extreme manifestations of early-twentieth-century post-millennial theology? In fact, these prize-winning sermons were simply the ablest written and most open examples of a broad shift in liberal or mainline Christian thought. In her brilliant and disturbing recent book, Conceiving Parenthood: American Protestantism and the Spirit of Reproduction, historian Amy Laura Hall shows how “eugenics gained popular support in large part through the endorsement of mainstream and progressive Protestant spokespersons.”

More importantly, Hall uses a meticulous study of 150 images of families found in both mainstream and Protestant media during the middle decades of the twentieth century to reveal how these churches injected a form of “soft” eugenics deep into American culture. She shows convincingly that this vision—resting on a eugenic form of birth control that emphasized child-spacing and precise gender balance—dominated mainline Protestant expectations through the 1950s.

The first signs of shifting Protestant views regarding birth control appeared—with some irony—in that para-church organization which had launched the career of Anthony Comstock: the Young Men’s Christian Association. As early as 1910, certain YMCAs were offering classes on “responsible parenthood” for “the betterment of the race,” which may have included instruction in the value of birth control.

Such attitudes spread within the organization. As an official in Hamilton, Ohio, reported: “Our local Y.M.C.A. is not sponsoring this work by official action, but sex education, including Birth Control for married persons, is accepted as a natural part of our program and that is sanction enough.” He praised “any technique . . . that will release sex from slavery to the procreative function [and] that allows normal sex function without fear of unwanted pregnancy.” Perhaps unaware of the origin of the Comstock laws, he also expressed personal interest in the “revision of legislation to make the dissemination of Birth Control knowledge legal.”

Sanger’s Preachers

There were other early recruits among the Social Gospel Protestants. Sanger won the support of Harry Emerson Fosdick (as noted earlier, a friend of the American Eugenics Society). As he wrote in his autobiography, “I was associated with the planned parenthood—birth control—cause early in Mrs. Margaret Sanger’s campaign, and on a few occasions have had opportunities to serve it.” Fosdick also blasted the “powerful, obscurantist” force of the Catholic Church for standing in the way of human progress.

Other early backers and correspondents with Sanger included the Rev. Howard Melish, a prominent Episcopalian in Brooklyn; the Rev. E. McNeill Poteat of the Southern Baptist Convention; the Rev. James Oesterling, superintendent of the Inner Mission Society of the Evangelical Lutheran Synod of Baltimore (who complained to Sanger about “colleagues who practice but do not preach birth control”); and the Unitarian leader, Rev. John Haynes Holmes.

A few articles indirectly favorable to birth control also appeared in the Christian press. A 1921 editorial in the Christian Advocate, a Methodist periodical, condemned Roman Catholic behavior in the Town Hall incident and praised the “earnest men and women” of the American Birth Control League, “whose laudable zeal for the welfare of the race has led them to advocate the artificial limitation of births.” A similar anti-Catholicism linked to soft eugenics appeared in the Baptist journal The Watchman—Examiner in 1926.

Still Officially Opposed

Later individual endorsements appeared in a symposium on “The Churches and Birth Control,” published in 1930 in the Birth Control Review. Soft eugenic language was common. The Rev. Jay Ray Ewers of Pittsburgh’s East End Christian Church, asked, “Why should the well-to-do be able to practice . . . Birth Control while the knowledge is forbidden to those who need it most?” The Rev. William W. Peck of the First Unitarian Church in Albany, New York, called it “the churches’ duty to advocate the cause of better-born children.” The Rev. Robert S. Miller of the Church of Our Father in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, defended the “two rights of childhood . . . the right of the child to be well born and the right not to be born at all.”

In a characteristic exaggeration, the editorial accompanying the symposium celebrated “the increasing support of all other [i.e., non-Catholic] denominations” and concluded that “with the churches in the vanguard, the cause of Birth Control is assured.” In fact, as of spring 1930, only one local American Christian group had formally embraced birth control (or two, if you count the Universalists). In April of that year, the New York East Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church endorsed a report of its Social Service Committee, which declared:

In the interests of morality and sound scientific knowledge we favor such changes of the law in the States of New York and Connecticut as will remove the existing restrictions upon the communication by physicians to their patients of important medical information on Birth Control.

A few months earlier, the Universalist General Convention, meeting in Boston, had approved a report calling birth control “the power to control the future of the race,” making it “one of the most practicable means of race betterment.”

That was it. The vast array of Protestant denominations—including the bulk of the Methodists—remained officially opposed to contraception.

Lambeth Breakthrough

This would begin to change over the following twelve months. Margaret Sanger’s first true “breakthrough” came with the Anglicans. She played a direct role here. Among her correspondents in the 1920s were several friendly Episcopalian bishops, whom she encouraged to push for change. After the House of Bishops of the Protestant Episcopal Church again in 1925 approved a resolution condemning birth control, an opportunity appeared. As Sanger reports in her autobiography, “some of the wives of these same bishops had come to me in New York and asked my help in educating their husbands.” This she attempted.

That 1925 meeting of the House of Bishops also expressed support for stricter marriage licensing so as to prevent “the marriage of persons of low mentality and infected with communicable disease.” This form of soft eugenics may have reflected the influence of William R. Inge, the dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and the leading Anglican intellectual of his generation. As early as 1917, he wrote an essay on “The Birth Rate” for the Edinburgh Review, in which he declared it futile to try to suppress a practice that most people believed to be useful and innocent. In a 1922 essay for the Birth Control Review, he dismissed talk of “race suicide” as absurd; the decline in the birthrate was “made necessary” by decreasing infant mortality and increased life expectancy.

Considering the higher fecundity of Roman Catholics when compared to Protestants, he proclaimed that a “high birth-rate always indicates a low state of civilization,” which he saw in Ireland, Italy, Poland, and other Catholic lands. In the face of primitive Catholic fecundity and with “England now breeding from the slums,” the eugenic case for birth control grew urgent. Inge traveled to America in early 1925, lecturing on behalf of eugenic groups.

In his speech to the 1921 Lay Church Conference, Lord Dawson of Penn, physician to the British king, lashed out at the Lambeth bishops. “The love envisaged by the Lambeth Conference is an invertebrate joyless thing,” he stated, “not worth the having. Fortunately it is in contrast to the real thing as practiced by clergy and laity.” Lord Dawson concluded: “Birth control is here to stay. . . . No denunciations will abolish it.” A year later, a confident C. V. Drysdale could tell the Fifth International Neo-Malthusian and Birth Control Conference that organized opposition among the Anglicans to birth control was over.

All the same, debate over birth control at Lambeth in August 1930 was heated. Opposition came in particular from (in Sanger’s words) “colonial and missionary bishops from distant quarters of the Empire.” Opponents also included a majority of the American delegates. However, on a vote of 193 to 67, with 46 abstaining, the Anglican bishops approved Resolution 15:

Where there is a clearly felt moral obligation to limit or avoid parenthood, the method must be decided on Christian principles. The primary and obvious method is complete abstinence from intercourse (as far as may be necessary) in a life of discipline and self-control lived in the power of the Holy Spirit. Nevertheless, in those cases where there is such a clearly felt moral obligation to limit or avoid parenthood, and where there is a morally sound reason for avoiding complete abstinence, the Conference agrees that other methods may be used, provided that this is done in the light of the same Christian principles.

So ended the 1,800-year-old Christian consensus on birth control.

An Echo in America

The first American echo of Lambeth came from the Federal Council of Churches of Christ in March 1931. As late as 1929, the FCCC’s Committee on Marriage and the Home had published a pamphlet deploring “the obsession of the stage and present day literature with sex, the disturbed condition of the home, a disquieting increase in divorce, and a growing laxness in the relation of the sexes,” developments “affected by a widespread and increasing knowledge of birth control.”

But around 1931 the Committee on Marriage and the Home issued a new report called Ideals of Love and Marriage, in which it concluded that a mother “needs to be out of the home as well as in it” and that “mothers, in order to provide their offspring with maximum opportunities in a fluid society, should have fewer children and ‘mother’ them less.”

This same committee composed a statement on birth control that affirmed “the rightfulness of intercourse in itself without the purpose of children.” Largely based on this principle, the statement reached the conclusion that “the careful and restrained use of contraceptives by married people is valid and moral.” The committee adopted the statement by a vote of 23 to 3.

Margaret Sanger was ecstatic. Upon the release of the FCCC statement, she proclaimed: “Today is the most significant one in the history of the birth control movement.” Meanwhile, she said, the Lambeth statement “was inevitably to lead the way toward the crystallization of a universal Protestant acceptance of the moral necessity of birth control.”

For its part, the Birth Control Review called the FCCC statement “epoch-making” and predicted that it would have “a profound effect on the various legislatures and on the mores of the country.” Incorrectly but significantly, it added: “Let it be remembered that it is the Catholics, not the non-Catholics, who have drawn the religious issue, and forced us to pit numbers against numbers.”

The FCCC Opposed

In fact, though, Sanger’s victory was very incomplete (which she surely knew). To begin with, the new birth control report almost tore apart the FCCC. Following a wave of lay and clerical protests, the Northern Baptist Convention resolved that the FCCC “did not speak for the Baptist denomination in endorsing birth control,” and it cut its financial contribution to the council.

In the Presbyterian Church USA, a revolt spread at the presbytery level; when the church assembly met in late May, conservatives elected one of their own as Moderator and they nearly succeeded in pulling the PCUSA out of the council. Down South, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States did vote, by 175 to 79, to withdraw from the FCCC, pointing to the birth control report as a sign of the futility of winning consensus on moral and political issues within “the Protestant Church.”

The FCCC report also generated a storm of protest among the Methodists. The Methodist bishop of Atlanta announced that the FCCC committee, in “sanctioning birth control under certain conditions, did not represent the Methodist Episcopal Church South.” Meeting in Atlanta in October 1931, the Sixth Ecumenical Methodist Conference received a report on “Marriage, Home and Family” drafted by the Rev. J. C. Broomfield. It condemned “the new abandon with which we write and talk on . . . such subjects as the science of eugenics, the education of youth in matters of sex, birth control, the use of contraceptives, [and] companionate marriage.” At the 1936 General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, delegates approved a resolution stating that “it is the major responsibility of Protestant Christianity to urge Christian people to recognize the importance of reproduction rather than . . . birth control.”

The Reformed Church–General Synod also threatened to leave the FCCC, pointing to the “unnecessary pronouncement of ‘Birth Control’ and ‘Usurpation of Authority’ as revealed in the ‘deliverance’ upon a moral question such as Birth Control.” And the United Lutheran Synod of New York resolved that the statement “expressed views distinctly opposed to the moral and spiritual teachings of the Lutheran Church;” it also came close to severing ties with the FCCC.

Secret Contributions

Indeed, financial pressures on the FCCC grew so acute that the group secretly asked Margaret Sanger to help raise emergency funds to cover the costs of lobbying those Protestant bodies opposed to birth control. She agreed, writing to a friend:

I want to send $300.00 to the Committee on Marriage and the Home. . . . This added to Mrs. Lawrence’s contribution will make $500.00, with which they can start something. I don’t want to give my check for various reasons so I am endorsing the enclosed check over to you . . . send it in as your contribution.

She added that she might be asking her correspondent to do this again, “because I am quite certain that the project of keeping the Committee working on Birth Control will be more worthwhile than any other single thing that we can do.” Between 1931 and 1934, Sanger and her second husband secretly donated about $2,000 (a hefty sum for the time) to the FCCC.

Even the post-Lambeth American Episcopalians proved wobbly. At the September 1931 General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church, delegates implicitly rejected birth control, approving a resolution stating that “there is no bond of unity so compelling, so rich and so joy-giving as that of children,” affirming “the necessity of children in the home,” and labeling “procreation” as the purpose of intercourse.

Three years later, Sanger resolved to try again. She dispatched her lobbyists to the Episcopalian convention, and sent copies of her agonizing Motherhood in Bondage to every American Episcopal bishop. On a close vote, the convention approved a resolution giving indirect support to birth control. Revealingly, though, it succeeded this time only by appealing to eugenics, endorsing “the efforts now being made to convey such information as is in accord with the highest principles of eugenics, and a more wholesome family life, wherein parenthood may be undertaken with due respect for the health of mothers and the welfare of their children.”

The Catholic Response

The most important reaction to the Lambeth statement was Pope Pius XI’s encyclical Casti Connubii, released on December 30, 1930. The pope saw the Catholic Church “standing erect in the midst of the moral ruin which surrounds her.” He acknowledged the reasons given by married people for wanting to restrict family size and then responded:

But no reason, however grave, may be put forward by which anything intrinsically against nature may become conformable to nature and morally good. Since, therefore, the conjugal act is destined primarily by nature for the begetting of children, those who in exercising it deliberately frustrate its natural power and purpose, sin against nature and commit a deed which is shameful and intrinsically vicious.

Given the link between birth control and eugenics among some Protestants, Pius also used this encyclical to clarify Catholic teaching on the latter. Referring to coerced sterilizations, he wrote: “Those who act in this way are at fault in losing sight of the fact that the family is more sacred than the state and that men are begotten not for the earth and for time, but for heaven and eternity.” Accordingly, it was “wrong to brand men with the stigma of crime” for wanting to marry despite hereditary defects.

Father John Ryan concluded from this that forced sterilization was “authoritatively declared to be intrinsically wrong,” and he resigned from the American Eugenics Society clergy committee with a blistering public note, calling its proposals “abhorrent for religious, moral, and social reasons.”

A Prescient Editorial

In a far less official, but more pointed manner, the Catholic journal Commonweal blasted the FCCC statement “as the liquidation of historic Protestantism by its own trustees, the voluntary bankruptcy of the Reformation.” Its editors acknowledged that this document had come from the theologically liberal side of the Protestant camp and that many in the churches involved were still opposed to birth control (including “the great Lutheran Church”). However, as the editors stated in prescient fashion, “it is likely that the struggle of the orthodox will be futile; that at best they will only be able to maintain a failing rear-guard action as they retreat to dig themselves in for their last battle.”

Indeed, the editors continued, liberal Protestantism had now become in practice “pagan humanitarianism, it is the creed of social science, built on the shifting and unstable experiments . . . of materialistic science.” These churches had in practice surrendered “a supremely important moral problem into the hands of a clique of birth control advocates.” The editors concluded by predicting that

legalized contraception would be a long step on the road toward state clinics for abortion, for compulsory sterilization of those declared unfit by fanatical eugenicists, and the ultimate destruction of human liberty at the hands of an absolute pagan state.

Opposition to birth control within the mainline Protestant churches did fade away by the end of the 1930s, partly for the reasons predicted by the editors at Commonweal and partly because of a 1936 decision by the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. In United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries, the judges now interpreted the federal Comstock law to allow “conscientious and competent physicians” to provide birth control information and devices “for the purpose of saving life or promoting the well-being of their patients.” The great Evangelical project of defending marriage and procreation through law, recently bolstered by Catholic activism, largely came to an end. Going forward, birth control would be primarily a moral issue, not a legal one.

A Guiding Principle

Indeed, Margaret Sanger had achieved her goals. As Kathleen Tobin notes, “Sanger ignored critics who said she would achieve success more quickly if she stopped antagonizing Catholics and in doing so she accelerated much of the non-Catholic support of her movement.” Her embrace of eugenics was also tactically brilliant, attracting Protestant clerics looking to racial improvement as a way of building the Kingdom of God on earth. At key points, such as the American Episcopalian turn in 1934, the eugenic argument proved decisive.

Where were the fundamentalists during the 1930s? In many respects, they were outsiders looking in, suspicious of Roman Catholic motives and appalled by the behavior of their Protestant brethren. Prior denunciations of birth control were allowed to stand, with little new said. To the degree it did grapple with family issues, the Southern Baptist Convention focused on denouncing divorce. Other fundamentalist writers called for a return to the Bible, leaving out the specifics.

A remarkable exception to all of these generalities was an editorial on “Birth Control” that appeared in 1931 in the Moody Bible Institute Monthly. It opened with enthusiastic praise for Pius XI: “We trust we shall not be accused of going over to Roman Catholicism if we speak approvingly of the late Encyclical of the Pope.” Indeed, “we wish all the great denominational bodies of Protestantism would be as positive and bold.”

The Moody editors also pointed approvingly to a recent speech in New York by the Catholic journalist “Gilbert Chesterton,” in which Chesterton labeled the “new morality a ‘filthy thing’ which ‘avoids birth and abandons control.’” As the encyclical taught, the laws of marriage “are made of God, not man” and “children should be received with joy and gratitude from the hand of God.” The editors concluded:

We cannot in this brief editorial go into all aspects of this grave subject, or even touch upon them, but we can warn our readers who have been redeemed by the precious blood of Christ and whose bodies are therefore the temples of the Holy Ghost, to see to it that they glorify God in their bodies which are His (1 Cor. 6:20). “Whither therefore ye eat, or drink, or whatsoever ye do, do all to the glory of God” (1 Cor. 10:3), is a principle to guide such in the contracting of marriage and afterwards in bearing its responsibilities as well as enjoying its blessings.

This clear, Bible-based rejection of birth control among the fundamentalists would face new challenges after World War II.

Select Sources

• Tom Davis, Sacred Work: Planned Parenthood and Its Clergy Alliances (Rutgers University Press, 2006).

• Peter Fryer, The Birth Controllers (Secker and Warburg, 1965).

• Amy Laura Hall, Conceiving Parenthood: American Protestantism and the Spirit of Reproduction (Eerdmans, 2007).

• Esther Katz, ed., The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume I: The Woman Rebel, 1900–1928 (University of Illinois Press, 2003).

• Esther Katz, ed., The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 2: Birth Control Comes of Age, 1928–1939 (University of Illinois Press, 2006).

• David M. Kennedy, Birth Control in America: The Career of Margaret Sanger (Yale University Press, 1970).

• Christine Rosen, Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement (Oxford University Press, 2004).

• C. Allyn Russell, Voices of American Fundamentalism: Seven Historical Studies (Westminster Press, 1976).

• Kathleen A. Tobin, The American Religious Debate Over Birth Control, 1907–1937 (McFarland and Co., 2001).

Allan C. Carlson is the author of numerous books, including Family Questions: Reflections on the American Social Crisis and The American Way: Family and Community in the Shaping of the American Identity. He attends St. Paul Lutheran Church in Rockford, Illinois. He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS

full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone

online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on abortion from the online archives

30.3—May/June 2017

Known Trespassing

on the Misuse of Property Rights to Justify Slavery & Abortion by Robert Hart

24.1—January/February 2011

Sanger's Victory

How Planned Parenthood's Founder Played the Christians, and Won by Allan C. Carlson

more from the online archives

31.2—March/April 2018

Watchful Dragons

Neil Gaiman’s Brush with Narnia Lingers by Russell D. Moore

31.1—January/February 2018

Beggars Before Christ

on Taking the Measure of the Deserving & the Undeserving Poor by Martin Bordelon

32.2—March/April 2019

What Gives?

on Properly Rendering Things to Caesar & to God by Peter J. Leithart

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor

Support Touchstone

00