Feature

The Cup of the Lord

Reflections on the Difference Between Martyrdom & Suicide Thirty Years After Jonestown

This past November 18th marked the thirtieth year since the massacre at Jones-town, where nearly a thousand members of the People’s Temple—followers of the charismatic preacher and activist Jim Jones—committed suicide in the jungles of Guyana. Most died by voluntarily drinking cyanide-laced Kool-Aid, thus establishing the common American colloquialism we know today cautioning against the manipulative and destructive effects of brainwashing.

Thirty years later, it is just as easy as ever to write off Jonestown as yet another example of cultic exploitation of a group of people who were naïvely utopian, overly credulous, or psychologically vulnerable. And yet there remains a certain perennial fascination with the event: Whether because it seems to provide an ever-fresh source of sensationalistic scandal to documentarists, or because it remains an ever-potent reminder of the dangers of overly premeditated communitarianism, it continues to haunt the American psyche, and especially the psyche of American Christians.

Why does the People’s Temple massacre maintain its hold on the American Christian psyche? I see two main reasons: first, because we rightly see it as a particularly perverted outgrowth of the distinctive sect-welcoming atmosphere of American Christianity; and second, because its grotesque deformation of the faith was in itself so undeniably demonic. It is the latter reason I want to take as the focus of some reflection.

Sacrifice to Demons

The Apostle Paul writes to the Corinthians—a community whose scandals might have rivaled Jonestown’s—“You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons too; you cannot have a part in both the Lord’s table and the table of demons” (1 Cor. 10:21). The Eucharistic parallelism of the Jonestown massacre—the fact that the community assembled in their customary place of worship and lined up in the aisles to drink from a common cup that would irrevocably manifest their fidelity—must strike even the least sacramental of believers as diabolically blasphemous.

Even on the most basic human level, one senses a degree of evil here that, though not unprecedented or unsurpassed, stings and bewilders in its forthrightness. Those who cannot bring themselves to call it demonic must at least feel the inadequacy of any less robust term for the sacrifice of the community’s children and elderly, which Jones made sure took place before the others.

“My opinion,” said Jones once the vat was ready, “is that you be kind to children and be kind to seniors and take the potion like they used to take in ancient Greece and step over quietly because we are not committing suicide; it’s a revolutionary act.” “Everybody keep calm and try and keep your children calm,” we hear one of Jones’s followers say; “let the little children in and reassure them. They’re not crying from pain. It’s just a little bitter tasting. They’re not crying out of any pain.” “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these” (Matt. 19:14).

“Look children, it’s just something to put you to rest,” we hear Jones say as the cup is administered. “We’re doing all of this for you,” we hear another woman cry out. “They worshiped their idols, which became a snare to them,” reads Psalm 106. “They sacrificed their sons and their daughters to demons. They shed innocent blood, the blood of their sons and daughters, whom they sacrificed to the idols of Canaan, and the land was desecrated by their blood.” “Children, it will not hurt,” exhorts Jones in his final mania. “Hurry, hurry, my children, hurry. All I think ( inaudible) from the hands of the enemy. Hurry, my children, hurry.”

For the Christian, it is insufficient simply to diagnose Jones or his followers with a specific—perhaps tailor-made—psychological disorder, nor will it do simply to let the atrocity speak for itself. Jonestown is neither a puzzle to be solved nor a historiographical curiosity. As Stanley Hauerwas once remarked,

what happened at Jonestown was not just a mistake but a form of the demonic that must be recognized and condemned. What went wrong at Jonestown is not that people died for what they believed but that they died for false beliefs and a false god. Their willingness to take their own lives demonstrates the demonic character of their beliefs.

Participation in Christ

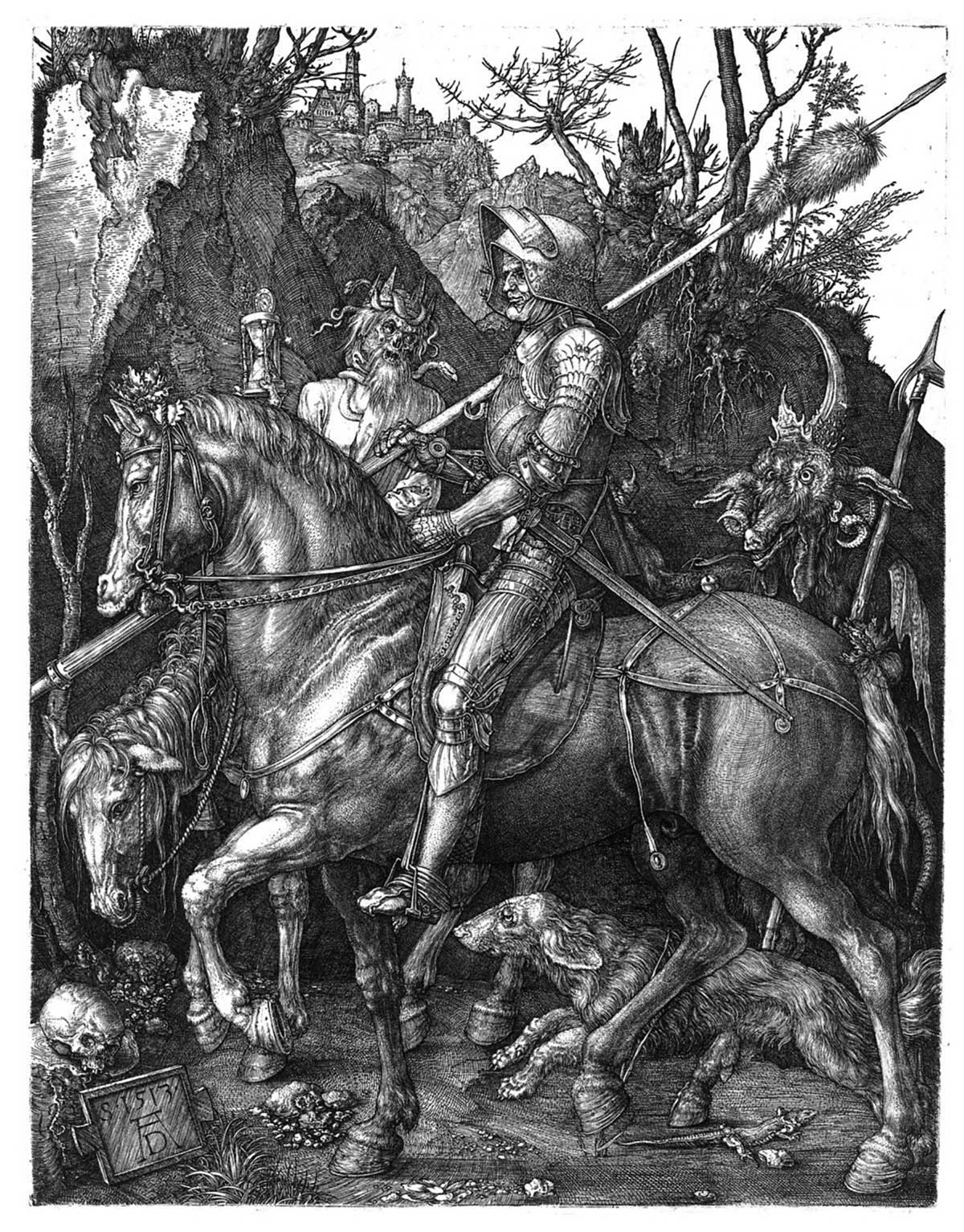

And so we must call it demonic, and render to it the aversion and contempt that is its due. But an important question should still nag at us: What exactly marks the difference between the demonic willingness of Jones’s followers to take their own lives and the Christian’s willingness to lay down his life for Christ?

In other words, what—theologically speaking—distinguishes this cup of demons from the cup of the Lord of which Christ’s followers are to partake? Paul reminds the Corinthians that “when you drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death” (1 Cor. 11:26), a death we in fact participate in through baptism (Rom. 6:3), and through the suffering and death we ourselves accept on behalf of Christ’s body (Rom. 8:17; 2 Tim. 1:8; 1 Peter 4:13).

Paul portrays this participation in Christ’s sacrifice as the path by which one may come to participate in his resurrection. “I want to know Christ,” he declares to the Philippians, “and the power of his resurrection and the fellowship of sharing in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, and so, somehow, to attain to the resurrection from the dead” (Phil. 3:10–12).

Elsewhere he tells the Colossians, “I am now rejoicing in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am completing what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church” (Col. 1:24). For Paul, the Church’s koinonia flows from its ongoing participation in Christ’s self-emptying sacrifice, an association that culminates in the fellowship of the Lord’s cup.

John the Evangelist confirms and extends this notion. “This is my commandment,” says Jesus in the Gospel of John, “to love one another as I have loved you. No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (John 15:12–13). He explicitly develops this concept so as to include sacrifice on behalf of others. “I have set for you an example, that you should do as I have done for you” (John 13:15). Indeed, the willingness to die for one’s friends is a part of his very definition of love: “We know love by this,” he writes, “that [Christ] laid down his life for us—and [so] we ought to lay down our lives for one another” (1 John 3:16).

Looking to the Saints

And yet Jonestown reminds us that we cannot ignore the potential dangers to which an unqualified endorsement of ultimate self-sacrifice can lead. Many modern critics have pointed out the various ways in which attitudes of self-denial and abnegation may contribute to pathologies of self-deception and exploitation.

Some feminist thinkers in particular, such as Brita Gill-Austern, argue that “the equation of love with self-sacrifice, self-denial and self-abnegation in Christian theology is dangerous to women’s psychological, spiritual, and physical health, and . . . contrary to the real aim of Christian love.” Liberation theologians have even argued that such theological concepts have helped perpetuate the unjust suffering of entire communities and peoples.

What should be the response of Christians to these challenges in light of tragedies such as Jonestown? In the face of so many examples in which the willingness to lay down one’s life for another has indeed occasioned sinful exploitation, how can Christians still defend the idea that such a willingness lies at the heart of the love that God has shown us and that he calls us to show to others?

Christian tradition suggests that the most economical, reliable, and ultimately compelling way to answer such a question is to look at how such theological ideals have been historically embodied in the lives of the saints, especially the martyrs. Let us therefore briefly examine a counter-narrative to Jonestown that is perhaps less well known in the American context: the martyrdom of

St. Charles Lwanga and his companions in late nineteenth-century Uganda.

Lwanga & His Friends

Marks of their legacy are everywhere in East Africa, where their memory continues to exert a transforming influence upon the society and culture. Charles Lwanga and his companions belonged to the Baganda people, a relatively advanced society ruled by a single leader called the Kabaka, who claimed authority over every aspect of civil and private life. Charles and his companions were servants in the court of Kabaka Mwanga.

The young men befriended one another naturally enough, living and working in the same setting. Their proximity also provided a fertile environment for the growth of their common faith. Those who had access to the missions would memorize verbatim enormous passages from Scripture or the catechism in order to instruct their fellow servants who were unable to leave the Kabaka’s compound.

As the Kabaka’s paranoia was nearing its peak, the royal pages would nevertheless risk death in order to secretly escape and visit the missions in the middle of the night. When it became apparent that they were in imminent danger of persecution, the catechumens sought baptism by the hundreds. Most were granted their wish, but many of the Kabaka’s servants could not escape because of tightened security. Charles Lwanga himself baptized over thirty boys on the night before their sentencing.

Kabaka Mwanga’s final fit of fury came in underwhelming and almost humorous fashion. He returned from a failed hippopotamus hunt and was in foul spirits. Seeing that none of his servants were around, he demanded to know where they were. One servant for whom he was asking in particular was a boy named Mwafu who had on past occasions succumbed to his sexual advances but had resisted since his conversion. When Mwafu returned and explained that he was with another servant named Ssebuggwawo, “learning religion,” the Kabaka proceeded to beat Ssebuggwawo to the verge of death with a large stick, and the final persecution was thus set in motion.

When the climactic moment came, the Kabaka is said to have asked those “who pray” to remain where they were, and those “who do not pray” to step forward and line up beside him. All but two of the servants (who were Muslim) stood their ground.

Dying Hand-in-Hand for Jesus

The Kabaka’s head chancellor pleaded with a personal assistant who had sided with the Christians: “Don’t be a fool. When have you learnt to pray? Don’t try to make us believe that you are one of them!”, to which the servant is said to have replied, “Most certainly I am. . . . Charles has been my instructor, model and protector, and I wish to die with him for Jesus.”

Not all were so unwavering, however. A survivor of the ordeal named Denis Kamyuka would later report that the youngest of the martyrs—Kizito, only 14 or 15—was terribly shaken by the Kabaka’s violence toward Ssebuggwawo. “From time to time,” Denis wrote, “an involuntary shudder shook his small frame. Charles tried to reassure him, his voice sweet and persuasive, ‘When the moment arrives, I shall take your hand like this. If we have to die for Jesus, we shall die together hand in hand.’”

But when the moment did arrive, the mood was quite different. Father Siméon Lourdel would give his own description of the boys being led out on the 37-mile march that would take them to the execution site, where they would be burned:

“They were bound so tightly,” he wrote . . . “that they could scarcely walk and kept knocking against one another. I saw little Kizito laughing at the odd situation. He looked happy, as if he were at play with his friends. . . .”

They spent the nights on their death march in this bondage, huddled together outside or in a tiny shack. Yet many apparently managed to sleep. “But if one of us happened to wake up,” Denis Kamyuka remembered,

he whispered to his neighbour, “I say, are you awake too? Tomorrow we are going to fight our battle; let us be firm in our resolve to die for Jesus Christ.” Each time we woke up, we recited our prayers. The Our Father and the Hail Mary were continually on our lips.

Denis would also recall the culminating moment when his friends entered the fire:

My eyes filled with tears and my throat was dry and constricted with emotion. . . . “Good-bye, friends,” they called, “we are on our way.” When [the executioner] saw that all was ready, he signaled to his men to station themselves all round the pyre, and then gave the order, “Light it at every point.” The flames blazed up like a burning house and, as they rose, I heard coming from the pyre the murmur of the Christians’ voices as they died invoking God. . . . The pyre was lit towards noon. . . . They prayed until they died.

Abandonment of Communion

In contrast to the friendship that sustained the Ugandan martyrs, there seems to have been a distinct counter-dynamic at work in the deaths at Jonestown, a depraved form of friendship that had its roots in Jones’s upbringing, during which he reports spending most of his time alone. In his adolescence, Jones became embittered by the neglect of his family and by the deaths of two people close to him.

When his adopted daughter Stephanie was killed in a car accident, his bitterness hardened into a practical atheism. Though he was a head pastor at the time, he confided to his close associates that he nonetheless did not believe in a God who would have allowed such suffering. In the eulogy he gave at his mother’s funeral, he coldly confessed, “The fact that she’s dead doesn’t change the fact that I resent her for bringing me into the world.”

Jones’s life was one long abandonment of communion with others, a drawn-out suicide committed in progressive stages over many years. He abandoned the many religious congregations of his hometown, which he thought inhospitable. As a pastor and preacher, he would later condemn those same churches (and in many cases quite justifiably) for their continued practice of racial segregation.

But he soon came to abandon religious tradition as a whole, and with it orthodox Christology, scriptural authority, and even theism. This steady distancing from religious tradition was paralleled by an increasingly radical alienation from established institutions in general, which eventually led to his exile from the United States and from society as a whole. He would eventually abandon his family and the very notion of family in favor of communalistic ideals and rampant promiscuity. In time, of course, Jones would abandon his own existence, along with that of his commune.

Death as Self-Assertion

What really separates this self-destructive alienation from a persistent willingness to “lay down one’s life for one’s friends?” For Friedrich Nietzsche, the only difference between a Charles Lwanga and a Jim Jones would be that the latter had greater consciousness of his own will-to-power. Both Nietzsche and Jones saw suicide as the ultimate assurance of the ability to determine the course and meaning of his own life: “The thought of suicide is a powerful comfort,” Nietzsche remarks in Beyond Good and Evil; “it helps one through many a dreadful night.” In Twilight of the Idols, he would explain further:

To die proudly when it is no longer possible to live proudly. Death freely chosen, death at the right time, brightly and cheerfully accomplished amid children and witnesses: then a real farewell is still possible, as the one who is taking leave is still there . . . all in opposition to the wretched and revolting comedy that Christianity has made of the hour of death.

In Human, All Too Human, Nietzsche would even rework the text of Luke 14:11 to read, “Everyone who humbles himself wills to be exalted.” For both Nietzsche and Jones, there can be no real sacrifice of self, only more circuitous or surreptitious strategies for its assertion. The noble person might conceive of dying at the hands of a friend (a worthy adversary), but dying for a friend makes no sense at all.

Like Nietzsche, Jones thought of suicide as an act of unconditioned will on behalf of personal honor. In his last recorded words, Jones assures his followers that “nobody has taken our life from us. We laid it down. We got tired. We didn’t commit suicide, we committed an act of revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world.”

Martyrs like St. Charles Lwanga, on the other hand, never spoke of their death as something they chose. When the Kabaka asked Charles whether he was resolved to profess himself a Christian, he replied, “Yes, quite definitely,” but added the caveat, “If you choose not to regard that as a crime, we shall be grateful to you, but we shall never cease to be Christians, whatever the outcome.”

Self-Created Heroes

Christian martyrs willingly sacrifice their lives only because they have first sacrificed their selves. “For you died,” Paul reminds the baptized at Colossae, “and your life is now hidden with Christ in God” (Col. 3:3). The identity of the saints is in a very real sense tied up entirely with another self, and they are willing to give and suffer all in order to preserve that relation.

For “self-created” heroes such as Jones, however, such constitutive dependence upon another is merely an encumbrance to be overcome. And, of course, the ultimate other to be overcome in this vein is God himself. In a sermon Jones gave to the People’s Temple in California, he boldly declared:

Why are there hungry children if there is a god? What’s your god ever done? Two out of three babies in the world are hungry. . . . He never heard your prayers. He never gave you food. He never gave you a bed. He never gave you a home. The only happiness you ever found was with me.

“If there is a god,” he would later proclaim, “or one who is decent and just and righteous, then I am the only one you’ll ever see who is like that.” Thus, Jones and the Kabaka bear a striking resemblance, not only in their absolute demand for allegiance, but also in the debilitating paranoia that leads both to induce mass slaughter. In both cases, the claim to absolute autonomy rendered friendship impossible because neither figure could acknowledge any common ground beyond themselves within which authentic mutuality could unfold.

Friendship of the Solitary

In his book The Politics of Friendship, Jacque Derrida goes beyond even Nietzsche’s heroic paradigm in providing what I see to be a haunting picture of Jonestown’s demonic imitation of divine friendship. One of Derrida’s primary points of reference is the Aristotelian aphorism, “O friends, there are no friends,” which Nietzsche (and Montaigne before him) took to refer to the solitude of greatness. From this solitude Derrida extrapolates his vision of the great person’s universal yet distanced friendship with humanity, a “friendship without memory of itself . . . bondless friendship . . . for the solitary one on the part of the solitary.”

For Nietzsche, an encounter with a friend was a welcome but temporary interruption of the great man’s solitude. Yet for Derrida, friendship always plays out within the world of the self. Friendship, like any act of the self, is always a unilateral assertion. Derrida thus describes the ideal friendship as an asymmetric, infinite gift, invoking the adage of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra: The friend “hath always a complete world to bestow.”

For Derrida, the exemplary friend provides for others a comprehensive vision of reality, a horizon, a self-created kingdom in which others may dwell as vassals. According to him, the great friend “gives a world, he gives all, he gives that in which all gifts may appear.”

This is precisely the sort of friendship Jones offered his followers: the gift of a world he himself embodied, in which they could live, move, and have being. One of his sermons even proclaims this totalistic aspiration: “I am peace; I am justice; I am equality; I am freedom; I am god.” Here we see in Jones what John Caputo has called Derrida’s “messianic . . . Dionysian rabbi,” a “slightly Jewish Zarathustra.”

A New Creation

But what about the messianic figure at work in the story of Charles Lwanga? Isn’t Jesus the original, more-than- slightly Jewish Zarathustra? After all, wasn’t he the first to say such things as “live in me”; “remain in me”; “I am the way, the truth, and the life?”

Here the paradoxical mystery of the Incarnation confronts us. In Christ, God extends himself in friendship to humanity. The universal “all” in which every particular subsists particularizes itself in the form of a man in order to establish a personal relation with each particular human being. It is the mark of the fallen angels’ rebellion to refuse this humility in disgust, and so attempt to un-create and re-create a world in which their own will might serve as a final limit.

One may thus construe the tragedy of the fallen world as a kind of self-enclosed quest for domination in the face of a Creator’s relentless self-emptying friendship, culminating in the shameful death of the Logos through whom all things came to be. And it is the same drama that in a sense characterizes human friendship as such.

St. John’s answer to whether the risk of befriending such a God is worth taking is the death of Jesus on the cross. For John, true friendship can only be identified in reference to that particular event. The Logos in whom all things came to be is the same Logos whose self-sacrifice allows friendship to unfold in a fallen world.

Christ’s friendship thus opens up nothing less than a new world, a new creation, revealing the Word’s willing self-sacrifice for friends as nothing less than the logic of God’s creation from the beginning. God’s “self-creation” is nothing else and nothing but the gift of self: the creation and redemption of other selves.

For the Christian, then, the ideal of self-sacrificial death is central, and so must be preserved and jealously guarded. As Jonestown reminds us, there is much at stake in the character of our deaths: They have the potential to be either the highest exemplification of God’s love or an unspeakable utterance of demonic sacrilege.

Near his end, Jones came to see that the only way to make the absorption of his followers final was to will their deaths as a part of his own. He admitted as much during one of his final suicide rehearsals: “I wanted to die, I guess. You care for people, you die, you die. So hell, death isn’t a problem for me anymore. . . . The last orgasm I’d like to have is death if I could take you all with me.”

Thirty years later, we can reaffirm our condemnation of this sacrilege by turning to Jesus’ own preparation for death: Seeing his end was near, he gathered his friends, shared a meal with them, recounted once again the redemption of Israel’s firstborn and—giving thanks—gave them the wine that would become his blood poured out for their sins. And in case they missed it, he arose and washed them clean. •

The quotations from Jim Jones are from the “Jonestown Suicide Tape” as transcribed by Mary McCormick Maaga in Hearing the Voices of Jonestown, and from Rebecca Moore, A Sympathetic History of Jonestown . Stanley Hauerwas is quoted from his “Self-Sacrifice as Demonic: A Theological Response to Jonestown” in Violence and Religious Commitment: Implications of Jim Jones’s People’s Temple Movement. Brita Gill-Austern is quoted from her “Love Understood as Self-Sacrifice and Self-Denial: What Does It Do to Women?” in Through the Eyes of Women: Insights for Pastoral Care . The quotations and descriptions of the martyrdom of Charles Lwanga and his companions are from J. F. Faupel, African Holocaust: The Story of the Uganda Martyrs.

Patrick Mahaney Clark is a doctoral candidate in Moral Theology at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. He is currently completing a dissertation on martyrdom as a moral and theological virtue. He and his wife Jennifer and their three children attend St. Michael's Byzantine Catholic Church in Mishawaka, Indiana.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on martyrdom from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor