View

The Making

of Lent

On the Origins of the (More or Less) Forty-Day Fast by William J. Tighe

What is Lent and what is its purpose in the Christian year? Most Christians would probably give an answer along these lines: It is a 40-day period of fasting and ascetic effort—or at least of heightened religious awareness—by which Christians prepare for the annual celebration of Christ’s passion, death, and Resurrection in Holy Week and Easter. Others might add that it is also a time when converts are prepared for their baptism or reception into the Church at Easter. And a few more might say that it is the Church’s corporate imitation of Christ’s 40-day fast in the wilderness after his baptism by John in the Jordan.

In fact, Lent is all three of these things, but it appears to have originated, in Egypt, exclusively as the third of these, and originally to have had no connection with the Lord’s passing through death to life. But before pursuing its origins, let’s do some backtracking.

Lent in East & West

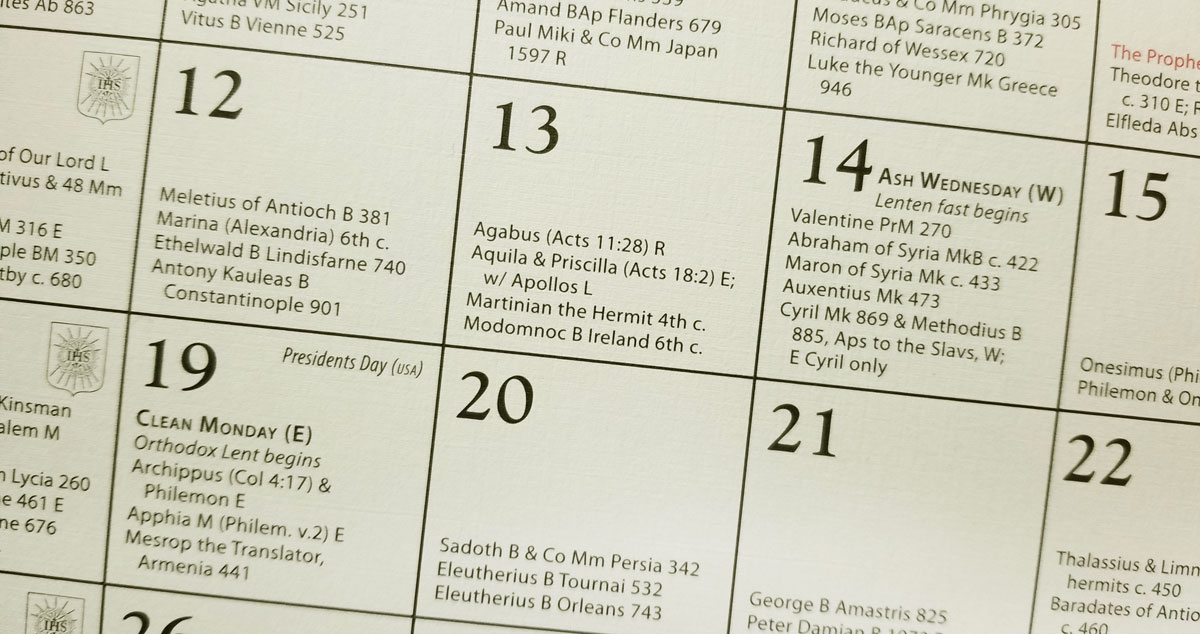

Let’s first imagine a year in which the Western Easter (calculated according to the Gregorian Calendar) and the Eastern Pascha (calculated according to the Julian calendar) coincide, which they usually do not, but in fact shall do in 2010, on Sunday, April 4. Let’s now compare the Eastern and the Western Lents.

In the West, among Catholics and Protestants alike, Lent will begin on Ash Wednesday, February 17, and end on Maundy Thursday, April 1. It is followed by the Holy Triduum of Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and Easter Sunday (April 2, 3, and 4). Sundays are not observed as fast days, so reckoning Lent as extending from Ash Wednesday to Maundy Thursday gives 38 days of fasting, to which the adding of Good Friday and Holy Saturday makes 40.

In the East, among both the Orthodox and Catholics of the Byzantine tradition, Lent, or the Great Fast, will begin after vespers on Sunday, February 14, and end on Friday, March 26, a period of 40 continuous fast days (with a slight relaxation on Sundays and on the feast of the Annunciation, March 25). It will be followed by two days outside the fasting season, Lazarus Saturday, March 27, and Palm Sunday, March 28, after which comes the separate fast of Great and Holy Week, running from Vespers on Sunday, March 28, to the great Paschal service of Matins and the Divine Liturgy in the night of Saturday–Sunday, April 3–4, which ends it.

In the West, Ash Wednesday and the immediately following Thursday, Friday, and Saturday were added to the beginning of Lent in the seventh century, when a concern arose with observing “40 fasting days” as opposed to “a fasting period of 40 continuous days, not all of which are observed with the same stringency.” Before that, Lent in Rome began a full week later than in Constantinople, on what was once known as Quadragesima Sunday, a Sunday anciently known in the West as Dominica in Capite Jejunii, the Sunday at the Head of Fasting. This is still the beginning of Lent in the Archdiocese of Milan and parts of adjacent dioceses, where the Ambrosian Rite (dating from the fourth century) is observed.

Preparation for Easter & Baptism

In both East and West, Lent was, for Christians, a period of ascetical preparation for the annual observance of the Lord’s “Passover” from death to life in Holy Week, and, for catechumens, a period of instruction and penitential asceticism leading up to their Paschal baptism. But now a curious difference between West and East comes into sight.

In Rome, these baptisms took place during the Easter Vigil, extending from late Saturday evening into early Sunday morning. But in Constantinople, they took place during the Holy Saturday liturgy (celebrated originally on Saturday evening but for most of the past millennium on Saturday morning), and not at the Paschal liturgy (beginning around midnight). More curious still, Lazarus Saturday, eight days earlier, is also a “baptismal day” in the Byzantine tradition.

Moreover, there is nothing specific about either the preparation of Christians to celebrate Easter, or the preparation of catechumens for their baptism, that points to a period of 40 days. At Rome in the early third century, and perhaps elsewhere, the prescribed fast for Christians preparing for Easter was limited to Friday and Saturday, although within the next century it had extended back to begin on Monday in Holy Week.

As for catechumens and their baptism, there is some evidence to suggest that in Rome at least, and possibly also in Jerusalem and adjacent regions, there was early on a three-week period of intensive preparation before Easter—perhaps related to the three-week period of preparation for Passover among Jews at this period.

St. Athanasius & the Fast

Although a full record of the acts of the Council of Nicaea of 325 does not survive, one of the actions attributed to it is the fixing, or prefixing, to Easter a fast of 40 days. Every indication is that this 40-day fast was of Egyptian origin, and, in its original purpose, was wholly unconnected with ascetical preparation for the celebration of the Lord’s passion, death, and Resurrection.

Rather, the ancient Egyptian fast was a commemoration and imitation of the Lord’s fasting in the wilderness for 40 days following his baptism by John the Baptist. This fast therefore began right after the feast of Epiphany, which celebrated the Lord’s baptism, and ended some considerable time, a matter of weeks, before Easter, but ended, nevertheless, with a climactic baptism of catechumens.

One of the duties of St. Athanasius the Great, as archbishop of Alexandria in the fourth century, was to determine annually for Egyptian Christians the date of Easter and the dates of the fast that preceded it. In his earliest such surviving letter, from the year 330, he announced that Easter would fall on Sunday, April 19, that the fast would begin on Monday, March 9, and that, within this fast, “the week of holy Easter” would begin on Monday, April 13. Interestingly, St. Athanasius includes all of Holy Week, including Good Friday and Holy Saturday in the fast, although he gives the last week separate mention in his letters.

This puts the Alexandrian practice of the fourth century together with that of Rome and Milan in considering Holy Week as the sixth and final week of Lent, as opposed to separating the two fasts by the interval of Lazarus Saturday and Palm Sunday, as was the practice of Constantinople by the latter part of the same century. (The practice followed in Antioch and Jerusalem at the time is unclear, although they both eventually conformed their practice to that of Constantinople.)

In a letter from 340 to Serapion, the bishop of Thmuis, Athanasius expresses concern that the Egyptian Christians not make themselves a laughingstock to the rest of the Christian world by not fasting when all other Christians are doing so, and he urges Serapion to proclaim the dates of the fast early and to teach and exhort the people to observe it. But in so doing, he never once mentions, as reasons for the fast, either following the Lord’s example or preparation for baptism. What is going on?

The answer may well be that this would have made too long a period of fasting to be bearable because, to the fast of 40 days that commemorated the Lord’s own fast, there would now be added the fast for the “new Nicene Lent.” The latter fast would begin shortly after, or even overlap, the commemorative fast.

This can be illustrated by returning to 2010 as our exemplary year. If a fast of 40 days were to begin on January 7, it would run through February 15. In the East, this date is also the first day of the pre-Paschal Lent of 40 days, while in the West, it is just two days before Ash Wednesday, February 17. This means that the whole period from January 7 to April 3 would be a continuous, or nearly continuous, period of fasting, which might well daunt or discourage even the most devout.

A Child of Egypt

January 6, Epiphany (meaning “manifestation”), or Theophany (meaning “manifestation of God”), was a great feast throughout the Christian East. It celebrated the manifestation of Christ as Messiah and as One of the Trinity—indeed, it manifested the Trinity itself—at his baptism in the Jordan, as well as his manifestation to the magi. Until the fourth century, when Eastern churches began to adopt the Western date of December 25, it also celebrated Christ’s hidden birth (manifested as it was only to his parents and the poor shepherds). In Egypt, this day was also the beginning of the church year.

That there was a fast following this feast, a very ancient Egyptian fast, can be demonstrated not only from documents of Egyptian provenance that precede the episcopate of St. Athanasius, but also from collections of church lore and memorabilia made by Coptic writers over the next thousand years, especially the fourteenth-century Abu ‘l-Barakat in his collection entitled The Lamp of Darkness.

From these sources it can also be shown that until 385, the Egyptian Church, unlike most other churches, did not practice Paschal baptism at all. In that year, the Patriarch Theophilus transferred the day of baptism to Holy Saturday from its “customary” and “appropriate” day, Friday of the sixth week of the pre-Nicene Egyptian fast that began immediately after Epiphany. These baptisms were the climax of that fast, and were followed by a festive weekend on which Sunday was “the Sunday of Palms”—a Palm Sunday that might precede Holy Week and Easter by as much as a month.

It thus seems that Lent, pursued backwards in twisting paths through time and history, has at last been disclosed to be a child of Egypt, a fasting period of 40 days that served both as a communal commemoration of Christ’s fast in the wilderness and as a preparation for the baptism of those to be received into the Church. It is the “ghost” of this baptismal day that survives in the baptismal elements of Lazarus Saturday in the Byzantine tradition.

In Egypt, the great fast originally had nothing to do with Easter; and Easter, strange as this may seem to Christians today, originally had nothing to do with baptism. It was the action of the Council of Nicaea that launched this fast into the Christian world generally. In variable and, at first, unstable ways, it was combined with older traditions of asceticism, Christian initiation, and the commemoration of the Lord’s passion, death, and Resurrection, before settling down into distinctive Eastern and Western patterns. •

William J. Tighe is Professor of History at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, and a faculty advisor to the Catholic Campus Ministry. He is a Member of St. Josaphat Ukrainian Catholic Church in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He is a senior editor for Touchstone.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on lent from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor