Devil Talk

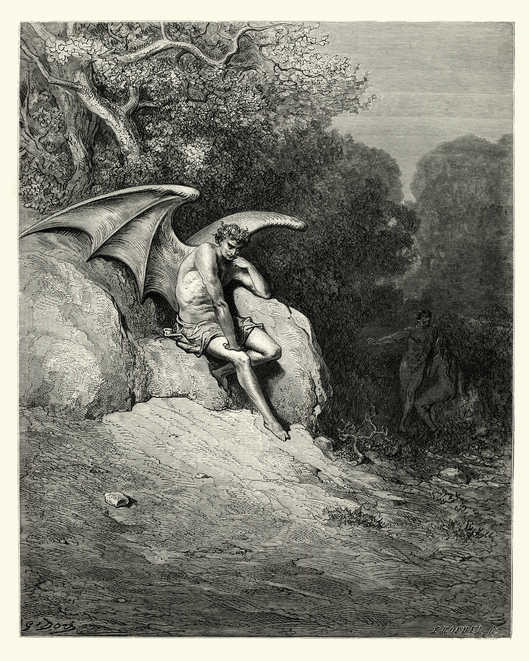

Milton’s Postmodern Satan & His Disciples

by Donald T. Williams

Suppose John Milton had asked himself, as he began writing Paradise Lost, “How would a person think who could do the kinds of things Satan has done? What view of the world could get a person to live that way?” If he had set himself just these questions, he could hardly have portrayed the answer in the philosophy of Satan more profoundly than he did.

Satan is not “unreasoning energy,” as one famous scholar put it. He reasons consistently and well, but perversely. And, as we will see, prophetically: His metaphysics and ethics, as they are generated by his epistemology, anticipate with stunning clarity late modernist and postmodernist thinking.

In three diabolical statements, Milton reveals the inexorable logic that explains why Satan did the kinds of things he did, and also the logic that would justify Satan’s actions to anyone who accepted his initial premise, or would condemn them for anyone who rejected it. These are statements that we hear, in different forms, today.

The Mind Its Own Place

The first words we hear from Satan record his shock at the contrast between the place where he finds himself and the place from which he has been expelled. Before he recovers enough to start putting his spin on the situation, he contrasts Hell’s “mournful gloom” with Heaven’s “celestial light,” its “horrors” most profound with “happy Fields/ Where Joy forever dwells.” Not to be deterred by anything so mundane as reality, Satan quickly turns to his rhetorical skills to salvage the situation, dramatically exhorting Hell to receive its new Possessor.

Possessor? To get the full effect, one must imagine an inmate just tossed into the Tower of London making this audacious speech while the Beefeaters roll their eyes and make significant gestures toward their heads as they pocket the keys, and hear Satan’s futile “Here at least we shall be free” echoing forlornly in the Tower’s hollow chambers. As Charles Williams said, “Hell is always inaccurate.”

Satan realizes that he needs to justify this defiance of reality, so he cuts quickly to the very foundation of the entire diabolical doctrine. His mind, he boasts, is not subject to change by so paltry a thing as place: “The mind is its own place, and in itself/ Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.” This is the first statement of the diabolical logic.

This claim is as philosophically audacious as the inmate’s claim to be the Tower’s new “owner” is legally absurd. Although Satan grudgingly admits that God has proven himself sovereign, and that this sovereignty includes the authority to “dispose and bid/ What shall be right,” he would have it that this situation only “now” obtains. Milton would have expected his readers to recognize in those words the centripetal force of Satan’s spin cycle.

Christian faith defines the Good as that which corresponds, not to God’s bare will, but to his will as the expression of his character, which is inherently good. Even Calvin, who is sometimes accused of teaching a bare voluntarism, held in the Institutes that God’s purpose in creation was “to manifest his perfections in the whole structure of the universe,” and “if it be asked what cause induced him to create all things at first, and now inclines him to preserve them, we shall find that there could be no other cause than his own goodness.”

If God is the creator portrayed in Genesis, it makes no sense to speak of good or evil except in relation to him. Satan’s claim thus denies God’s claim to be God. For if God created the world, the mind is not its own place; it is, like every other place, God’s place. God has already determined what is good, and for the mind to strike off in a different direction is both a perverse and a doomed enterprise.

Satan is rejecting what in The Abolition of Man C. S. Lewis calls “the doctrine of objective value.” “Until quite modern times,” Lewis explains,

all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it—believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence, or our contempt.

He then illustrates this with an example:

To call children delightful or old men venerable is not simply to record a psychological fact about our own parental or filial emotions at the moment but to recognize a quality that demands a certain response from us whether we make it or not.

One need not be a Christian to accept this view: In an appendix, Lewis documents an impressive consensus on it across the world in pre-modern times. But to be a Christian is to be logically committed to the objectivity of value because the doctrine of creation radically grounds the existence of objective value in the character and decrees of God, who not only spoke the world into existence but pronounced it “good.”

Milton’s Satan correctly realizes that to claim the right to choose—or, indeed, create—his own alternative values, he must eliminate that grounding. His claim that the mind is its own place is not merely a justification for his rebellion; it is his rebellion in its very essence.

Our Own Good from Ourselves

We can now see why I said that Satan’s metaphysics and his ethics are generated by his epistemology. He does not say, “This is the nature of reality; therefore, this is what we can know about it.” He says, “This is how I choose to know the world; therefore, this is what that world is like.”

In other words, he has decided that one does not discover truth, meaning, and value, as is proper for a creature; one creates them for himself, as is proper for God. The truth is not “out there,” but in the mind that is its own place.

From this subjectivist epistemology flows an antirealist metaphysic. This place where the demons now find themselves is not Hell because of objective realities like flames that give off “darkness visible.” It is Heaven because Satan says it is. What do these commitments do to Satan’s ethic, his conception of the good?

The answer is given, not by Satan himself, but by one of his minions, Mammon. Rejecting the thought of returning to Heaven to worship One whom they hate, he urges the demons to “seek/ Our own good from ourselves, and from our own/ Live to ourselves,” even if they must do so in Hell. This is the second diabolical statement.

With it, Mammon lays out the next logical step down the path Satan has chosen. If the good is that which corresponds to God’s will as the expression of his character, as Christianity teaches, then the search for the good must lead us out of ourselves, proximately to the grateful reception, as God’s gift, of that which he has made, and ultimately to communion with God himself.

But if the mind is its own place and the good is that which corresponds to its assertion of its own will, the search for the good must lead us into ourselves, for only there, in the mind’s own place, exist the Heavens we have tried to make out of our own Hells.

If God is the source of all goodness, all other beings are related to each other through him. Their common pursuit of a common good leading back to God is the source of community, of a common unity in the enjoyment of a shared good, which is the basis of love.

This is the life of Heaven, which the faithful angels enjoy and into which Adam and Eve are invited. But if the mind is its own place, it must reject all this and validate for itself any “good” it chooses.

And it must do so alone. For every other individual is in the same position, and even if two of them agree on the same good and seek it together, their community has no basis other than their own self-referential and arbitrary choices. How far can one trust another ego that is as committed to its own sovereignty, its own divinity, as one’s own is? That is why the demons have no understanding of love and grace. Devil may with devil damned firm concord hold, but they do so out of fear, as Satan admits.

It is noteworthy that Satan has a philosophy, but no political philosophy, though this lack is mightily obscured by the ubiquity of his political rhetoric. As one scholar has shown, Satan’s rhetoric parodies the goal of what Milton would have considered the “righteous” Puritan revolutionary who wanted to abolish kingship in favor of democracy, while his actual rebellion is that of tyrants as Aristotle describes them in The Politics: rebels who want to keep the same form of government (monarchy) but simply “wish it to be in their own control.”

The mind as its own place, egocentric by definition and design, leads naturally to isolation and fragmentation. The unity imposed on that fragmentation by Satan’s strength of will is the normal definition of Hell, though Satan may call it Heaven if he will.

Evil Be Thou My Good

If the mind is its own place, it can only seek its own good from itself. What kind of good can it expect to find? Satan is later tempted (privately) to repent, only to harden his heart and recommit himself to evil. But he finds that escaping the Hell he has chosen is not a simple matter of redefining it in the mind’s own place. Milton’s narrator deflates all of Satan’s big talk about making a Heaven of Hell by telling us that

horror and doubt distract

His troubl’d thoughts, and from the bottom stir

The Hell within him, for within him Hell

He brings, and round about him, nor from Hell

One step no more than from himself can fly

By change of place.

The ironic reprise of the word place can hardly be insignificant. Satan reproaches himself for his ingratitude to God in a soliloquy he would never have allowed his demons to overhear. This forfeiture of all that is truly good weighs heavily on him, so that “Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell,” a condition that threatens only to worsen eternally. Nevertheless, he will not repent because repentance entails submission. He thinks it better to reign in Hell than to serve in Heaven.

But where does this leave him? Satan accepts the fact that “all Good to me is lost.” He is under no illusions about who the ultimate Source of Good in the universe is, however many illusions he may generate for his followers. And so we reach the place to which Satan’s choice has inexorably led: “Evil be thou my Good.”

Satan’s premise that the mind’s secession from God’s rule to become its own place will allow it to make a Heaven of Hell has utterly failed, and it can be maintained henceforth only as the most cynical of lies. This third diabolical statement thus becomes the official philosophy and public policy of Hell.

Adam and Eve will discover bitterly when they subscribe to it that an inescapable logic of damnation flows from Satan’s original premise. “Evil be thou my good” is the inevitable result of the mind’s secession from the kingdom of Heaven. And though he stubbornly clings to his philosophy as the only alternative to “submission,” even Satan can no longer pretend—except to others—that what it has brought him is good.

Instructively Wrong

Satan is tragically and perversely wrong, of course, but he is wrong in a most instructive way. As C. S. Lewis wrote so perceptively in A Preface to Paradise Lost, “‘Evil be thou my good’ entails ‘Nonsense be thou my sense.’” It is no accident that Satan’s most faithful (post)modern disciples also offer us a world in which the establishment of meaning is endlessly deferred in a kind of reading that is a game without goals, the free play of a mind that is insistently its own place, leading nowhere because “there is nothing outside the text,” as Jacques Derrida famously put it.

Is the mind its own place or God’s place? Everyone must choose. One can follow God and have meaning or follow Satan and have Deconstruction. It is as simple as that.

Milton anticipated nihilistic, Derridean postmodernism three hundred years in advance by trying to figure out how Satan thinks. In the world of the poem, Heaven and Hell are not interchangeable, and the rejection of one lands a person inexorably in the other. The choice that is central to our own time is the one Milton wanted his seventeenth-century readers to ponder, the one he believed Adam and Eve had also faced, and Satan and the heavenly host before them.

We have only now caught up to the clarity with which Milton’s Satan presented that choice to himself (though he was not so forthright with Adam and Eve). Our first parents have already chosen for us in the Garden, but we are offered in Christ the opportunity to unmake that choice for ourselves: no longer, like Satan, to “seek/ Our own good from ourselves, and from our own/ Live to ourselves,” but to find again in our good Lord the Source of all that is true, beautiful, and good. •

The “famous scholar” quoted is E. M. W. Tillyard; the second scholar quoted is David Loewenstein, writing in the Spring 1992 issue of the Huntington Library Quarterly; the quotation from Charles Williams is taken from his “An Introduction to Milton’s Poems,” reprinted in Milton Criticism: Selections from Four Centuries, edited by James Thorpe; and the quotation from Derrida is taken from his Of Grammatology. A more scholarly version of this essay appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of The Journal of the Georgia Philological Association.

Donald T. Williams Ph.D., is Professor Emeritus of Toccoa Falls College and the author of Deeper Magic: The Theology Behind the Writings of C. S. Lewis (Square Halo Books, 2016) and Ninety-Five Theses for a New Reformation: A Road Map for Post-Evangelical Christianity (Semper Reformanda Publications, 2021).

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on philosophy from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor