Grave Signs

Russell D. Moore on the Godly Waste of Christian Burial

I knew my grandfather’s funeral wouldn’t be elaborate or expensive. He was a big-hearted Baptist, generous with his grandchildren but spending little on himself. This was a man who refused the “luxury” of air-conditioning in south Mississippi, a place where most people consider air-conditioning a necessity.

He left instructions that he didn’t want anyone spending money on a casket, embalming fluid, or an elaborate funeral. He wanted to be cremated, the cheapest way possible to dispose of his earthly remains. No one asked my opinion on this, but I wept bitterly at the thought of this great man being reduced to ashes in the twinkling of an eye.

I could understand my grandfather’s request. He was a practical man who wanted to save money for his family. And the financial racket of cushioned caskets, catered “celebration services,” and steel-vaulted graves is a scandal, to be sure. What I couldn’t understand was how few of my fellow Christians joined in my horror at the thought of a Christian man’s cremation.

Of all the issues of controversy among Christians, I find few more incendiary than whether or not we should, well, incinerate the bodies of our loved ones. I find that Christians become agitated, defensive, and personally insulted more quickly on the question of cremation than on almost any other contemporary question. And I find this odd.

A Christian burial seems, in this culture, more and more nonsensical: a waste of money, a waste of otherwise usable land, a waste, perhaps, even of emotion, as we try to “hold on to the past” and fail to “move through our grief and get on with life.” But if someone had asked any previous generation of Christians or of pagans if cremation were a Christian act, the answer would have seemed obvious to them, whether they were believers or infidels: Christians bury their dead.

Today, however, an anti-cremation stance is often ridiculed by Christians as, at best, Luddite and, at worst, carnal. When I counsel a family to reject the funeral director’s cremation option, I am often asked: “Can’t God raise a cremated Christian just as he can raise a decomposed buried Christian?” The question is more complicated than whether God can reconstitute ashes. Of course he can. The question is whether we should put him in a position of having to do so in the first place.

Better to Bury or to Burn?

Stephen Prothero’s landmark study, Purified by Fire: A History of Cremation in America, demonstrates that cremation flourished before Christianity and withered away when the Church spread through Europe and beyond. Prothero argues that cremation was virtually unknown in early America, its proponents limited to anti-Christian “freethinkers” who saw in the act of cremation a defiant rejection of the resurrection of the body.

Most Christian cremation proponents dismiss the history of cremation ideology as irrelevant to the discussion, as simply a version of the genetic fallacy. After all, few Christians cremate with any thought of nineteenth-century debates, much less of ancient paganisms.

And the Church has toned down its previous horror at the thought of cremation. The Catholic Church, for instance, lifted its formal disapproval of cremation, stating in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, “The Church permits cremation, provided that it does not demonstrate a denial of faith in the resurrection of the body.” And the “freethinkers” among us are consumed with other things these days than funeral rites.

It is interesting, however, that cremation rates are high in areas of North America least touched by Christian memory: in the Pacific Northwest, for example. One would be hard-pressed to find a more predictable map of the so-called Bible Belt than to look at the states where cremation is still least socially acceptable: from the Catholic/Baptist gumbo of Louisiana through the mountains of eastern Kentucky and West Virginia.

This is not to say that Bible Belt Christians have a theological position on cremation; most don’t. There is an unthinking, almost instinctive revulsion, a revulsion that can thus be lost in the decades to come.

And, indeed, traditionalist Catholics and fundamentalist Christians may well be hyper-scrupulous when they see in cremation a pagan act. But the question very rarely is even considered: Were the atheists and Gnostics of yesteryear on to something when they saw in cremation a statement of belief, or the lack thereof? Were our Jewish and Christian forefathers doing something theologically and personally meaningful when they buried their dead?

Some Christians chafe at the discussion because there is no Bible verse forbidding cremation. This charge is especially relevant to a Protestant such as this author, who believes in the Reformation principle of sola Scriptura.

But sola Scriptura does not mean that Scripture is the only authority to which one should listen, but that Scripture is the final and non-negotiable authority, the norm that norms all other norms. I look to Mapquest, not to Leviticus, to find my way from Louisville to Chicago, but if Mapquest—or the Third Vatican Council or the Executive Committee of the Southern Baptist Convention—tells me there was never a City of Jericho, I submit to the authority of Scripture over theirs.

Moreover, sola Scriptura has never meant merely a concordance approach to the Bible (Where’s a verse on sex reassignment surgery? Not one? Then it’s fine? Well, no). There is a comprehensive storyline to Scripture, against which we must judge our actions, especially the actions of our churches as we testify to the reality of the gospel.

Burial Care

The question is not simply whether cremation is always a personal sin. The question is not whether God can reassemble “cremains.” The question is whether burial is a Christian act and, if so, then what does it communicate?

Of course God can resurrect a cremated Christian. He can also resurrect a Christian burned at the stake, or a Christian torn to pieces by lions in a Roman coliseum, or a Christian digested by a great white shark off the coast of Florida.

But are funerals simply the way in which we dispose of remains? If so, graveyards are unnecessary, too. Why not simply toss the corpses of our loved ones into the local waste landfill?

For Christians, burial is not the disposal of a thing. It is caring for a person. In burial, we’re reminded that the body is not a shell, a husk tossed aside by the “real” person, the soul within. To be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord (2 Cor. 5:6–8; Phil. 1:23), but the body that remains still belongs to someone, someone we love, someone who will reclaim it one day.

Our father Abraham did not “dispose” of the “container” previously occupied by his loved one. Moses tells us that “Abraham buried Sarah his wife in the cave of the field of Machpelah east of Mamre (that is, Hebron) in the land of Canaan” (Gen. 23:19, emphasis mine). His burial of his wife, returning her to the dust from which she came, honored our foremother, in precise distinction from the shamefulness with which our God views the leaving of bodies to decompose publicly (Is. 5:25).

The Gospel of John tells us that “Lazarus had already been in the tomb four days” (John 11:17). The Holy Spirit chose to identify this body as Lazarus, communicating continuity with the very same person Jesus had loved before and would love again.

After the crucifixion of Jesus, the Gospels present us with an example of devotion to Jesus in the way the women—and Joseph of Arimathea—minister to him, anointing him with spices, specifically anointing, Mark tells us, him and not just “his remains” (Mark 16:1), and wrapping him in a shroud. Why is Mary Magdalene so grieved when she finds the tomb to be empty? It is not that she doubts that a stolen body can be resurrected by God on the last day. It is instead that she sees violence done to the body of Jesus as violence done to him, dishonor done to his body as dishonor to him.

When Mary mistakes Jesus for the gardener, she tells him she is despondent because they “have taken away my Lord, and I do not know where they have laid him” (John 20:13). This body was, at least in some sense, still her Lord, and it mattered what someone had done to it. Jesus and the angelic beings never correct the devoted women. They simply ponder why they seek the living among the dead.

Graveside Eschatology

Scripture also tells us that there is a specifically Christian way to grieve, not “as others do who have no hope” (1 Thess. 4:13). Christian grief, the way the Christian community deals with its dead, signals what it believes to be true about the dead in Christ.

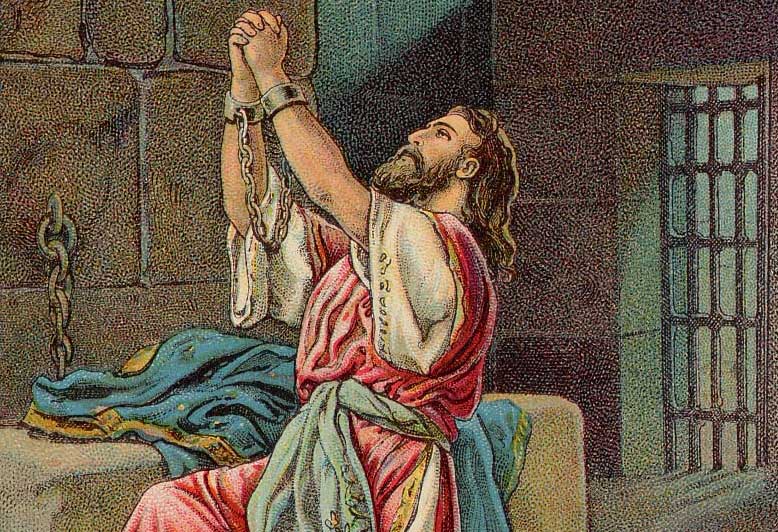

This is why God deems as faith Joseph’s committing his bones to his brothers for future transport into the land of promise (Heb. 11:22; Gen. 50:25). Why does this matter? Cannot God resurrect Joseph in Egypt, and deliver him to Canaan at the last day? Joseph of all the sons of Israel understood the providence of God (Gen. 50:20). But God saw in Joseph’s concern for his bones, that they be with the people of God in the land he promised them, to be an act of trust.

After all the years of wandering, the miracles, the suffering, the bloodshed, that brought the Israelites into the land, the capstone of the conquest of Canaan was the men of Israel burying the body of Joseph at Shechem (Josh. 24:32). Joseph’s eschatology was seen in the way he committed his bones to his brothers—and in the way they honored them as a testimony to his faith and theirs.

Burial is a fitting earthly end to the life of a faithful Christian, a Christian who has been “buried with Christ in baptism” and is waiting to be raised with him in glory (Rom. 6:4). A Christian burial does not mean that we are “in denial” about the decomposition of bodies—that is part of the Edenic curse (Gen. 3:19). It does mean that this decomposition is not what, in this act of worship, we proclaim as the ultimate truth about the one to whom we’ve said goodbye.

Burial conveys the image of sleep, the metaphor Jesus and his apostles used repeatedly for the believing dead (John 11:11; 1 Cor. 15:51; 1 Thess. 4:13–14). It conveys a message, a message quite different from that of a body already speed-decayed, a body consumed by fire.

The Voice of Jesus

We should not find it unusual when Christians are the last ones left to picture death graphically with the image of sleep. The metaphor of sleep doesn’t mean that the dead are unconscious, but that they will be awakened.

When Jesus was called to the home of the synagogue ruler’s daughter, he quieted the funeral mourners by saying, “She is not dead but sleeping.” And in one of the most poignant passages of Scripture, Luke tells us, “And they laughed at him, knowing that she was dead. But taking her by the hand he called, saying ‘Child, arise’” (Luke 8:53–54).

Christians at a burial site remind themselves and the watching world, by committing a seemingly “sleeping” body to the ground, that one day this same northern Galilean accent will ring from the Eastern skies—and “they that hear shall live” (John 5:25).

I suppose I shouldn’t find the heat that comes from the cremation debate all that surprising. It is deeply personal, especially for those of us with loved ones resting now in urns or scattered beneath oak trees or embedded in man-made reefs off the coast. What bothers me as a Christian minister is not so much that some of us are cremated as that the rest of us don’t seem to care.

Like the culture around us, we tend to see death and burial as an individual matter. That’s why we make our own personal funeral plans, in the comfort of our living room chairs. And that is why we ask the kind of question we ask about this issue: “What difference does it make, as long as I am resurrected in the end?”

Recognizing that cremation is sub-Christian doesn’t mean castigating grieving families as sinners. It doesn’t mean refusing to eat at the dining room table with Aunt Flossie’s urn perched on the mantle overhead. It doesn’t mean labeling the pastor who blesses a cremation service as a priest of Molech.

It simply means beginning a conversation about what it means to grieve as Christians and what it means to hope as Christians. It means reminding Christians that the dead in the graveyards behind our churches are “us” too. It means hoping that our Christian burial plots preach the same gospel that our Christian pulpits do.

I wish my grandfather hadn’t been cremated. As I preached his funeral, I wished I could join with centuries of Christians in committing his body, intact, to the ground. I hated his cremation, but I didn’t hate it as others do, as those who have no hope. Instead, I thanked a faithful God for a great man’s life.

And then I paused in recognition, knowing that one day the wisdom of the embalmers and the power of the cremators will be put to shame by the Wisdom and Power of God in the eastern skies above us. And I expect it will be glorious to see what the voice of Jesus can do to a south Mississippi funeral home’s medium-price urn.

Russell D. Moore is president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention. He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor