Feature

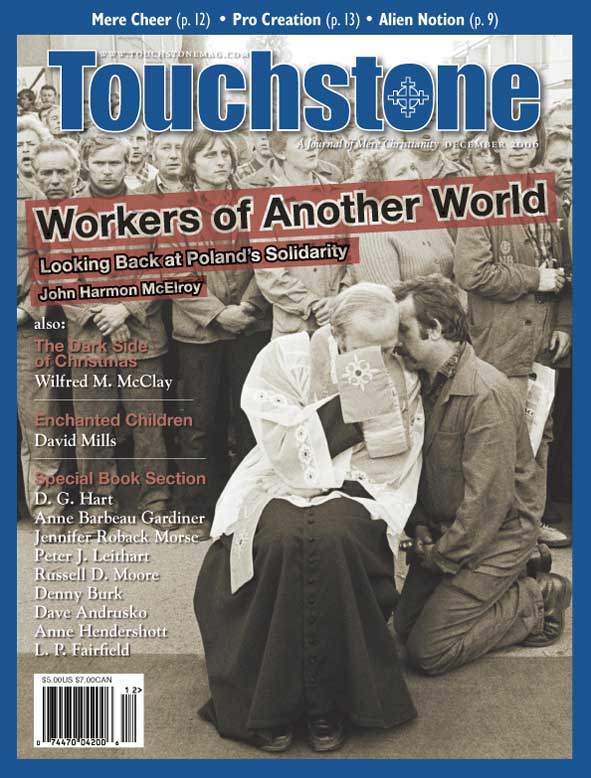

Workers of Another World United

A Personal Commemoration of Poland’s Solidarity 25 Years Later

The 1981 summer English Seminar in Poznan, Poland, had ended, and the twenty-six British and American instructors and the more than two hundred students had gathered for the farewell party. A young woman from one of my classes told me of John Paul II’s first visit to Poland as pope and the pilgrimage she and her classmates made to Czestochowa to worship with him at the shrine of their homeland’s holiest icon, “the Black Madonna,” at Jasna Gora.

“There we were with the Holy Father,” she said, “thousands of us, praying silently with him, and you could feel the power rising up through the trees.” From the way she said this, I knew that what she said was true, and that what she was describing was the power of the Holy Spirit, which in the summer of 1981 in Poland was as palpably present to me as the country’s tawny wheat fields, turbid rivers, and leafy woodlands.

In class, my students never spoke of religion. But there was something in the manner of a good many of them—a peacefulness of demeanor, a kindly way of addressing each other—that suggested the inner serenity of deeply held Christian beliefs. A couple of the instructors at the seminar called this “the Solidarity spirit.”

They were referring, of course, to the formative Christian spirit of the labor union the Poles called Solidarnos´c´ (“Solidarity” in English) that was also a national freedom movement whose general strike the previous summer (1980) had compelled the communist government of Poland to grant it legal status. Just a few months later, in December 1981, twenty-five years ago this month, the union would be outlawed and many of its leaders imprisoned.

But without the visit of John Paul II to Poland in 1979, there would have been no Solidarity in 1980. And without Solidarity in Poland in 1980, there would have been no disintegration of the Iron Curtain nine years later, no crumbling of the Soviet empire, and no dissolution of the Soviet Union itself in 1991.

A Sustaining Spirit

Inevitably, in a nation so deeply imbued over the centuries with the teachings of Roman Catholicism, almost all of the workers who joined Solidarity were communicants of that religion. But it was the elevation of John Paul II to the papacy and the powerful sermons he preached during his visit to Poland in 1979, on the Christian concepts of the dignity of human beings as children of God and the dignity of labor, that gave this national labor union its uniquely Christian spirit of solidarity and dedication to the principles of nonviolence and truth-telling. This spirit and these principles proved to be the main sustaining strengths of the union.

My students patiently explained to me the connection between Pope John Paul II’s visit to Poland and the founding of Solidarity. After the conclave of his fellow cardinals elected him head of the Roman Catholic Church in 1978, Karol Wojtyla naturally wanted to visit his beloved native country. And his countrymen wanted him to come. After all, it was no small matter in a country where 97 percent of the people professed Roman Catholicism that a Polish cardinal had become the first non-Italian pope in five hundred years.

The central committee of the Polish Communist party, however, did not share their fellow Poles’ happiness over Wojtyla’s election. Nor did they desire a papal visit. But popular sentiment for a visit was intense and widespread. If the party withheld permission, would that not look like weakness? Would that not seem like fear of one man and what he might do?

So permission was granted, with the proviso that the Catholic Church would have to organize the logistics for his travels in Poland without any help from the government. No state resources would be made available.

It would have been far better for the leaders of the Communist party in Poland and their continuance in power had they been able to honor the new Polish pope and pledge their support for his visit. But of course a communist government could not do that. In Poland under communism, as in the Soviet Union, the government never acknowledged God’s existence, and religious belief was not allowed to have anything to do with public life. The politics of communism is a strictly “secular,” i.e., atheistic, politics.

Faced with the novel mandate of being in charge of a national event, Polish Catholics gladly undertook the required tasks and marshaled the necessary material support for a series of massive public gatherings from one end of Poland to the other that were de facto challenges to the regime. An estimated 13 million Poles attended the outdoor Masses the pope conducted during his nine days in Poland. In his homilies, he spoke of freedom and workers’ rights.

The nationwide communications that were developed in coordinating the pope’s activities in Poland in 1979 became, the following year, the non-governmental network of communications that facilitated the astonishingly rapid growth of Solidarity.

National Christian Labor

In the history of organized labor, the Polish labor union Solidarity is unique. The closest thing to it might be the American Railway Union (ARU), organized and led by Eugene V. Debs in the 1890s.

The ARU was an industrial union, the organization of workers in an entire industry. It included workers who built the railroad cars and engines, laborers who laid and repaired railroad track, trainmen, switchmen, charwomen, and every other kind of worker in the railway industry. The American labor movement, however, did not go for industrial unions, but instead favored trade unions, the organization of workers according to trades, so that carpenters belonged to one union, steelworkers to another, and so on.

Solidarity was an organization of workers throughout a nation. It was a national labor union. The only prerequisites for joining were being Polish and having a job. Solidarity’s members included office workers and bricklayers, store clerks and dishwashers, schoolteachers and streetcar drivers, glassblowers and garbage collectors, journalists and electricians, coal miners and ballerinas, welders and movie directors. The unprecedented scope of this labor organization is indicated by the fact that representatives to its national governing body were elected not by trades but by cities and regions.

Eventually, 87 percent of the Polish workforce became dues-paying members of Solidarity. And the size of its membership, of course, was a large part, though not the primary component, of its strength in the 1980 strike led by Lech Walesa, the shrewd 39-year-old shipyard electrician who became Solidarity’s chief spokesman and leading negotiator. The other components of the union’s strength were its insistence on nonviolence and telling the truth.

The general strike in Poland in August 1980 was the only strike ever in a communist-ruled country that did not result in bloodshed. Repeatedly—in 1956, in 1968, in 1970, and again in 1976—Polish workers protested against high prices, low pay, and food shortages. Each protest involved street demonstrations and work stoppages, and each had been put down by military force. The strike pulled off by Solidarity in 1980 had a radically different configuration. It was a nationwide peaceful work stoppage.

In 1980, workers did not take to the streets carrying signs and banners of protest and images of the Black Madonna, the patroness of Poland. They stayed in their workplaces. With enormous courage and discipline, they passively dared the government’s troops to attack them there, where all they were doing was issuing written demands, praying, singing patriotic songs, confessing to the priests who came to minister to them, and receiving Holy Communion.

And of course this tactic of massively organized Christian nonviolence had a radically different result. On August 31, 1980, two weeks after the general strike began, several of Solidarity’s most important demands, including a forty-hour workweek and recognition of Solidarity as a legitimate union representing the interests of Polish workers, independent of the phony, communist trade unions set up by the government, were agreed to in formal accords signed by representatives of Solidarity and the government.

The name the Communist party had chosen for itself was “the Polish United Workers Party,” and that, the strike proved, was what Solidarity in truth was.

Devout Poles

To appreciate fully the appearance behind the Iron Curtain of a Christian-based labor union like Solidarity, enrolling ten million workers, certain facts peculiar to Poland’s modern history must be appreciated.

The principal one is that Poland vanished from the political map of Europe in 1795, having been gobbled up by the three imperial powers on its borders—Russia, Germany, and Austria—and did not reappear until 1919. (More than one of my students in Poland in 1981 thanked me, because I was an American, for Ronald Reagan’s support for Solidarity and for what Woodrow Wilson did for Poland at the Versailles peace conference after World War I by insisting on its restoration.)

That the nation survived its more than a century of suppression was due largely to the Catholic Church in Poland, whose schools kept Polish patriotism alive from generation to generation. During those years, being a devout Catholic became synonymous with being a good Pole.

The restoration of Polish sovereignty in 1919 was short-lived. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Poland was again dismembered, and after the war it was reduced to a captive nation in the Soviet empire. The war did more, however, than result in the imposition of a puppet government controlled from the Kremlin. As a consequence of World War II, Poland suffered the loss of a larger proportion of its population than any other nation in Europe.

World War II started with coordinated invasions of Poland from the west by Nazi Germany and from the east by the Soviet Union. The two invaders swiftly overran the country in 1939 and divided it, according to previous agreement, between them. Then, in 1941, Germany invaded Soviet-occupied eastern Poland, driving out the Red Army. Three years later, the Soviet counterattack entered eastern Poland and battled westward across the entire nation.

Because the country suffered four invasions during the Second World War, the slaughter of six million Poles in Hitler’s death camps in Poland (half of them Polish Jews), and four years of partisan warfare following World War II, it did not regain the level of population it had had in 1939 until 1978.

The devastation and death in Poland between 1939 and 1949 occurred before any of the students I had in class in 1981 were born. Nonetheless, they spoke to me of those events as if they themselves had survived the war.

Giving Hope

There were other signs of the ordeals the nation had suffered and was continuing to suffer. Some buildings in Poznan still showed the pockmarks of rifle and machine gun fire, and at every hand was evidence of the shortages the Polish people were putting up with. The food rationing. The dusty emptiness of shelves and display cases in stores. The rundown condition of public buildings. The vacant look of weariness on the faces of people standing in blocks-long lines outside stores with something to sell.

Poles in 1981 bought whatever was available, in as large a quantity as possible, for barter was a daily necessity of the stressful way of life in communist-governed Poland. It was called kombinowac´, “to make combinations.” A housewife, I was told, might spend up to five hours a day in queues and on the phone making combinations.

Then, too, there was the private tennis club for Communist party officials I passed every time I went to the US Consulate in Poznan, whose clay courts were always in use by male and female players dressed in fashionable tennis clothes. Students of mine informed me that Communist party bigwigs had taken over the hunting lodges and game preserves of the prewar Polish nobility; some party officials, I was informed, had yachts and villas on the Mediterranean, where they relaxed from the rigors of running Poland for the good of the people.

In 1981, in flying from West Germany to communist Poland, one left an animated world of color, light, and comfort and entered a dismal, half-dead, twilight world of stupefying ideology. It was from the despair that life under communism induced that Pope John Paul II roused his countrymen.

He gave them hope. He reminded them, and the rest of the world, that the dignity of man derives from the sanctity of human life, which derives from belief in God the Creator. He gave them faith in themselves as God’s creations. He told the long-suffering people of Poland to be unafraid of their oppressors. He inspired a nonviolent freedom movement in the largest communist-governed country in Europe outside the Soviet Union.

Pope John Paul II preached the need for liberating the soul, in opposition to the Marxist idea (which is the Darwinian idea) of man as only another animal, with only a material origin and physical needs. He preached peace, mercy, freedom, and self-determination; communism demanded slavish submission to a political party and central planning and in return delivered privation and moral degradation. In the communist takeover of Central Europe after World War II, many eggs had been broken but the promised omelet had not been produced. The pope’s message was that of St. Paul: be strong in Christ, be free through trusting in God’s truth.

Pope John Paul II would later write that his pastoral message to the world came down to a choice between “the culture of life” and “the culture of death.” Under his influence, the people of Poland in 1979 and 1980 chose life. Ten years after they made their steadfast commitment to that choice, the Soviet empire disintegrated.

Unmasking Evil

On December 13, 1981, sixteen months after signing the accords recognizing Solidarity as a lawful union, the communist regime outlawed Solidarity and declared martial law. Lech Walesa and tens of thousands of other elected leaders and supporters of Solidarity were rounded up (some of them killed in the process) and imprisoned.

When the Polish United Workers Party declared war on the united workers of Poland, 34-year-old Father Jerzy Popieluszko was assistant pastor of the Church of St. Stanislaw Kostka in Warsaw. A priest totally devoted to his vocation, sincere, gentle, and an extraordinarily gifted speaker, he was instantly liked by one and all.

He had become involved with Solidarity in 1980 when he answered the call of the striking workers at the giant steel plant in Warsaw for a priest to hear confessions and conduct Masses for them. He stayed with the steelworkers, spiritually ministering to them, until the strike ended, and he came away from the experience with a great affection for the workers, which they reciprocated. He later admiringly said to an interviewer: “Those people understood that their strength lay in God, in the unity within the Church.”

At the risk of being imprisoned under the provisions of the martial-law decree, which prohibited any expression of support for Solidarity, Father Jerzy decided to protest the government’s attempt to destroy the union. He announced in his church that on the last Sunday of each month his 7 o’clock evening service would be a Mass for Poland.

He conducted the first of these Masses in January 1982, six weeks after the government outlawed Solidarity. He told those who attended the services, which came to be known as “Masses for the Country,” such things as: “All of the wrongs committed against the people must be put right, and we should sit down at a table intending to find the way out together. The common goal should be reconciliation—the well-being of the country and respect for human dignity.”

He told them to be forgiving and to pray for their fellow Poles in the government, saying, “Let us be strong through love, praying for our brothers who have been misled, without condemning anybody but condemning and unmasking evil.” He said: “The source of our captivity lies in the fact that we allow lies to reign, that we do not denounce them . . . that we do not confront lies with the truth but keep silent or pretend that we believe in the lies.”

He said: “Let no one say that Solidarity has lost.” He said: “Solidarity is the unity of hearts, minds, and hands rooted in ideas which are capable of changing the world for the better. It is the hope of millions of Poles. The more that hope is united with the source of all hope—God—the stronger it becomes.”

Freed from Fear

Soon the Church of St. Stanislaw Kostka could not hold everyone who wanted to attend Father Jerzy’s Masses for the Country. The congregation spilled out into the churchyard, then into the square in front of the church. Loudspeakers were installed and priests brought in to distribute Communion. Finally, the congregation filled even the streets that led into the square in front of the church. As many as ten thousand people at a time came each month.

The government did not like having its propaganda called lies and Poles told to be unafraid to speak the truth. It did not like someone openly defying its ban on support for the outlawed union. What was it to do about this popular priest who would not obey the decree outlawing support for Solidarity, who put conscience above the power of the state, who fearlessly spoke out against the fear and the lies that were needed to maintain socialism in Poland?

The government’s propagandists denounced Father Jerzy in the government-controlled press. They said he was conducting “séances of hate” and “black masses” of an “anti-state character.” They complained that he publicly prayed for persons arrested under the martial-law decree and took up collections of money for their families; that he transformed “a religious gathering into a political demonstration, risking a breakdown of law and order”; that he abused “freedom of conscience and religion”; that he slandered “the supreme organs of the state authorities”; that he was “turning churches into places for anti-state propaganda harmful to the interests of the Polish People’s Republic.”

State security police tailed Father Jerzy wherever he went. His phone was tapped. He was repeatedly taken to the Ministry of the Interior for questioning. His car was vandalized. A bomb (which failed to explode) was thrown through a window next to his bedroom. Then the police “found” two hand grenades in his room, and an indictment was prepared on July 12, 1984, accusing him of possessing explosives. He was brought into court on this accusation but was neither tried nor imprisoned.

On October 19, 1984, Father Jerzy and his driver, while returning to Warsaw from Bydgoszcz, a town in northern Poland, were forced to pull over by three men. He and the driver were taken from their car, bound, and put in their abductors’ vehicle. Father Jerzy’s driver managed to open a door and throw himself out, and escaped. Eleven days later the young priest’s battered body was found, weighted down with rocks, in a reservoir.

A thousand priests were needed to distribute Communion to the 300,000 people who attended the funeral mass for Father Jerzy Popieluszko, whose last words in the final sermon of his life were: “Let us pray that we may be free from fear and intimidation, but most of all that we may be free from the desire for violence and vengeance.”

He was but one of hundreds of Poles who were murdered during the communist government’s unsuccessful attempt to eliminate Solidarity, including the auxiliary bishop of Gdansk and a university chaplain in Poznan. Around the time of his murder, five other priests were also kidnapped and either tortured or beaten, but not killed.

Solidarity’s Strength

Despite the government’s attempt to eradicate Solidarity, the people of Poland remained firm throughout the 1980s in their faithfulness to Solidarity’s Christian ideal of nonviolent resistance to evil. And the hundreds of Poles who sacrificed their lives in the 1980s in the cause of defending human dignity, and the many thousands more who lost their freedom and their livelihoods in the same cause, suffered not in vain.

The union members who were not arrested had carried on. They went underground. They continued to publish the truth about communism in Poland and the suffering its policies were causing. The lie that the Polish United Workers’ Party represented the interests of workers was forever exposed.

In going back on its promise to recognize Solidarity, the regime lost its moral authority, which is much more powerful than any authority based on weapons that can kill. In continuing to resist without violence, Solidarity gained a moral authority based on the conviction that man possesses, as God’s special creation, rights that the state cannot rescind, rights that take precedence over any interest of the state.

After nine years of nonviolent resistance, the spirit of Solidarity prevailed. Free elections were held in Poland in 1989. And candidates who ran for office on the Solidarity platform won a strong majority in the parliament. Lech Walesa was elected to the presidency of the new government.

Before my return to the United States from Poland in 1981, a student of mine took me to see the monument that Solidarity had erected in Poznan that year as a memorial to those who died in this city in 1956, in the first Polish workers’ protest against communist rule. The monument he wanted me to see consisted of a pair of towering metal crosses and a monolith, surmounted by an eagle symbolizing Poland, inscribed with the words “For Freedom, Law and Bread.”

On that day in 1956, Poznan’s main square was packed with townspeople and the workers who had marched into town that morning from the train repair shops and other industries on the city’s outskirts. Some of the crowd went to the government facility that jammed Radio Free Europe broadcasts into Poland and smashed its equipment, then went to a prison to free political prisoners. The first deaths occurred there, as the mob overpowered the guards and seized their weapons.

At noon, tanks from the local garrison arrived on the scene to restore order, but their crews went over to the side of the people they were supposed to shoot. The tanks were used to assault and destroy the local headquarters of the Communist party. At 8 o’clock that evening, military forces from outside Poznan moved in. They did not completely quell the uprising until 5 o’clock the next morning.

The museum next to the crosses, which documented, with photographs, this violent workers’ uprising, listed by name 77 people who died and indicated that another 50, whose names could not be ascertained, had probably lost their lives as well.

It was this sort of violence that Father Jerzy preached against and that the spirit of Solidarity prevented between 1980 and the elections of 1989, which marked the effective end of communist rule in Poland and of the Soviet era of empire. Every one of the earlier confrontations, beginning in 1956 and repeated in 1968, 1970, and 1976, ended in a bloody defeat for the protesters. The general strike of 1980, in which workers lay down on the job, prayed, confessed to priests, and took Communion, passively daring the government’s troops to attack them, succeeded.

Overcoming Fear

That is what I saw in Poland: Christian faith in God-given human rights overcoming the fear that communist governments employ as the basis for government: Fear of losing your job or not being promoted if you don’t act with political correctness according to communist doctrine and say what that doctrine requires you to say. Fear of not having your son or daughter admitted to a university if you deviate. Fear of being arrested as an enemy of the people if you criticize the party that theoretically represents the people. Fear of public humiliation and slander. Fear of imprisonment.

The people of Poland, both high and low, both intellectuals and workers, overcame their fear because of the faith in themselves as God’s creatures that John Paul II inspired and animated in them. What happened in Poland in the 1980s was Christian theology in action.

Something that a Solidarity officer named Lech Dymarski told me in 1981 epitomizes this change. When I asked him what he thought the future might hold for his country, he simply said: “The communists will never again be able to make us feel small.”

It was this sort of Christian self-confidence that Father Jerzy Popieluszko communicated in his public sermons, saying:

The essential thing in the process of liberating man and the nation is to overcome fear. . . . We fear suffering, we fear losing freedom or our work. And then we act contrary to our consciences, thus muzzling the truth. We can overcome fear only if we accept suffering in the name of a greater value. If the truth becomes for us a value worthy of suffering and risk, then we shall overcome fear.

Father Jerzy’s words and the government’s complaints about him are taken from Grazyna Sikorska’s Jerzy Popieluszko: A Martyr for the Truth (Eerdmans, 1985).

John Harmon McElroy is Professor Emeritus of the University of Arizona. As a Fulbright Professor of American Studies he taught at universities in Brazil and Spain. He is the author of Divided We Stand: The Rejection of American Culture Since the 1960s (Rowman & Littlefield), published earlier this year. He and his wife have four children and ten grandchildren. Because of his experience in Poland, he says, he has been a communicant of the Roman Catholic Church since 1983.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on communism from the online archives

19.10—December 2006

Workers of Another World United

A Personal Commemoration of Poland’s Solidarity 25 Years Later by John Harmon McElroy

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor