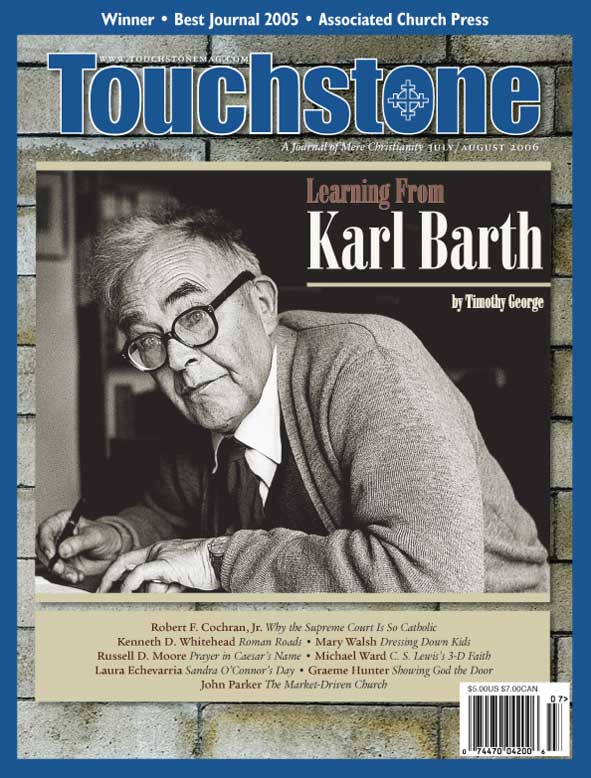

An Ecclesiastical Mind

An Evangelical Appreciation of Karl Barth

by Timothy George

The Church runs like a herald to deliver the message. It is not a snail that carries its little house on its back and is so well off in it, that only now and then it sticks out its feelers, and then thinks that the ‘claim of publicity’ has been satisfied. No, the Church lives by its commission as a herald; it is la compagnie de Dieu.

— Karl Barth, Dogmatics in Outline

I was first introduced to the thought of Karl Barth in an undergraduate course on “contemporary” theology. We were asked to read The Word of God and the Word of Man, a collection of Barth’s early sermons and addresses, and though I was not then, and still am not now, a Barthian with a capital “B,” Barth grabbed me right from the start.

Unlike Bultmann’s demythologizing and dismantling of the biblical worldview and Tillich’s abstruse philosophy of religion—they, and a few others, were the “canon” in those days (the sixties)—here was a theology that spoke to the heart, that held high the revelation of God in Holy Scripture, and that was also presented in such a provocative, passionate, and personal way. Here was theology presented as though something eternally important was at stake. Here was a theology that mattered.

Barth’s New World

When I began formal theological studies at Harvard Divinity School, Neo-Kantian and liberationist paradigms prevailed there, and Barth, when mentioned at all, was treated as only of antiquarian interest. But my doctoral studies propelled me back to the Reformation, especially to the connection between the doctrine of election and ecclesiology, and this in turn forced me back to Barth. I remember plowing through Barth’s discussion of predestination in the second volume of his Church Dogmatics and discovering there “a strange new world” I had not encountered before.

True, I shared many of the standard Evangelical reservations about Barth, such as his tilt toward universalism and his challenge to biblical inerrancy, but I knew that I had something to learn from him, especially about the Church. Even though I would not have called him “the great Church Father of Evangelical Christendom, the one genuine Doctor of the universal Church the modern era has known,” as the editors of the English edition of his Church Dogmatics did shortly after his death in 1968, it was clear that I had encountered a titanic figure whose work, I believed, Evangelicals could ill afford to ignore.

From his early days as a young country pastor in Switzerland, Barth understood theology as a spiritual discipline within the community of faith, “the scientific self-examination of the Christian church with respect to its distinctive God-talk,” as he put it at the very beginning of the first volume of Church Dogmatics. But despite this commitment, he could be acutely critical and negative in his statements about the Church. This was especially so in his early writings, where the gospel is depicted in stark opposition to the Church.

The two realities cannot co-exist, for “the gospel dissolves the church and the church dissolves the gospel,” he wrote in his Commentary on Romans, published in 1922. “In the Church,” he declared,

the ‘Beyond’ is transfigured into a metaphysical ‘something’ which, because it is contrasted with this world, is no more than an extension of it. In the church, all manner of divine things are possessed and known, and are therefore not possessed and not known. . . . In the church, faith, hope, and love are directly possessed, and the Kingdom of God directly awaited, with the result that men band themselves together to inaugurate it, as though it were a thing which men could have and await and work for.

The Church, Barth seems to say, has become not a means to God but rather a substitute for God, an idol. He put it like this: “Only when the end of the blind alley of ecclesiastical humanity has been reached is it possible to raise radically and seriously the problem of God.”

Blessed Terribleness

Failures and abuses, no matter how great, were mere trifles compared to what in the commentary Barth calls “the blessed terribleness” of “the Church which is the very Word of God—the Word of beginning and end, of the creator and redeemer, of judgment and righteousness.”

In this dialectic the Church is divided into two parts: the Church of Esau and the Church of Jacob. By this designation Barth does not refer to confessional differences, say, between Roman Catholics and Protestants, nor to theological camps such as conservatives and liberals. Drawing on Paul in Romans 9, he refers instead to the distinction grounded in divine predestination.

The Church of Esau is “observable, knowable and possible,” whereas the Church of Jacob, where the truth of the gospel triumphs over all human deceit, is

unobservable, unknowable, and impossible . . . capable neither of expansion nor of contraction; it has neither place nor name nor history; men neither communicate with it nor are excommunicated from it. It is simply the free grace of God, his calling and election; it is beginning and end.

Here we are at the headwaters of Barth’s dialectical ecclesiology. It is not hard to see why those with a vested interest in the Church—any church—would respond to Barth’s rhetoric with consternation and reproach. If the Church is utterly unknowable, unobservable, so detached from history that one cannot speak of it properly, then very practical questions ensue: To whom do we pay our tithes (or church taxes in the state churches of Europe)? Who shall train the church’s ministers, and how? Who shall write the church’s liturgy, and lead its worship, and send out its missionaries, and do its pastoral care? Such questions arise naturally for Protestants, Catholics, Quakers, and Anabaptists alike.

It has always seemed to some of Barth’s critics that his “bifurcation” of the Church would lead inevitably to ecclesial nihilism. But this is to miss the deeper point Barth is making. It was necessary to be so decisively against the Church, he believed, precisely in order to be so unreservedly for it. Even in Romans, where the language of diastasis—positing a Yes for every No, and vise versa—reaches fever pitch, Barth always remains with both feet firmly planted within the physical, finite, fallen, Esau-like church.

We must not, because we are fully aware of the eternal opposition between the Gospel and the church, hold ourselves aloof from the church or break up its solidarity; but rather, participating in its responsibility and sharing the guilt of its inevitable failure, we should accept it and cling to it.

We must bear the tribulation of the Church as participant-observers. Only through sharing its anguish are we able to pray for revival and work for reformation.

In Part Heretically

Interpreters of Barth do not agree themselves as to what extent his thought is marked by steady development or by major breaks and new trajectories. Barth himself pointed to some significant shifts in his thinking along the way, although late in his life he could also claim continuity and once boasted that, unlike Augustine, he had not found it necessary to publish a volume of retractations.

In any event, he later recognized that some of the language he had used in Romans was a little over the top. He admitted in The Humanity of God, published in 1960 (he died in 1968), that he had spoken “somewhat severely and brutally, and moreover—at least according to the other side—in part heretically.” What is clear is that he found a more constructive way to describe the Church and its role in relation to the gospel and to the revelation of God in Jesus Christ. “If I am a theologian,” he wrote late in his life, “I must try to work out broadly what I think I have perceived as God’s revelation. Yet not I as an individual but I as a member of the Christian church. This is why I called my book Church Dogmatics.”

From the 1920s onward the image that came to dominate his ecclesiology was that of herald or witness. To be sure, this image can be found in his earlier writings as well. Already he had discovered Matthias Grünewald’s famous depiction of the Crucifixion, originally painted for the chapel of a hospice at Isenheim. Grünewald was an early sixteenth-century painter from the Rhineland who may possibly have embraced the message of Luther near the end of his life.

What drew Barth to this painting was Grünewald’s portrayal of John the Baptist. John stands at the right of the cross with an open Bible in one hand while he points with the other to the tortured figure of Christ in the agony of death. In faded red letters behind John are the Latin words: Illum oportet crescere, me autem minue, “He must increase, while I must decrease” (John 3:30). In his famous typology of modern ecclesiologies, Models of the Church, Avery Dulles has rightly characterized Barth’s approach with the rubric, “The Church as Herald.” This image became even more important in Barth’s opposition to the “anti-Christian counter-churches” of Nazism.

Barth’s Real Church

After the war, in 1948, Barth addressed the first General Assembly of the World Council of Churches, which met in Amsterdam. He spoke on the appointed theme: “Man’s Disorder and God’s Design.” He criticized the post-war optimism that prevailed in many ecumenical circles. “We shall not be the ones who change this wicked world into a good one. God has not abdicated his Lordship over us.”

One of those who listened to Barth’s remarks was a young 29-year-old evangelist from America who had come to the assembly as a representative of the Evangelical revival movement Youth for Christ. His name was Billy Graham. Over the next fifty years, Graham rather than Barth would take the lead in shaping the worldwide Evangelical movement. Barth heard Graham preach on one occasion and referred to him as a “jolly good fellow,” but criticized his Evangelical salesmanship. Barth appreciated the missionary zeal and vitality of the Evangelicals, but he considered their lack of serious interest in the Church and its theology a serious weakness.

In the same year Barth spoke in Amsterdam, he also traveled to Hungary to deliver an important lecture on “The Real Church,” published two years later in the Scottish Journal of Theology. It reflected both his intense engagement with Roman Catholicism and his wider ecumenical involvement at this time. His ecclesiology, set forth in this seminal essay, would both compliment and challenge Evangelical understandings of the Church. In this essay, we can identify five major themes that reflect Barth’s thinking about the Church, themes he would continue to reflect on and develop during the next two decades of his life.

First, the real Church becomes visible only through the power of the Holy Spirit. Barth here sounds a note that recurs frequently in his writings about the Church: The Church is an object of faith, as all Christians affirm in the Apostles’ Creed, credo ecclesiam. Thus, the Church is not like the state, the family, or the municipality in which we live, all of which are human communities that can be defined empirically, studied sociologically, and the like.

Although one can also study the Church as a religious community, that is, apart from a commitment of faith, this is not the Church confessed by Christians in the creed. That Church is an event, a happening, that can only be seen by the eyes of faith when the Holy Spirit “enables her to step out of and shine through her hiddenness in ecclesiastical establishment, tradition, and custom.” Just as a neon sign remains dark and obscure until a current of electricity floods it with color, light, and movement, so too the Church is a lifeless form apart from the energy and vitality given to it by the Holy Spirit.

Jesus the Head

Second, Jesus Christ is the Lord as well as the Head of the Church which is his Body. The real Church is the congregation of lost sinners called together by Christ and bound to him through the miracle of divine grace. The connection between Jesus Christ and his Body on earth is genuine and inviolable, so much so that Barth would later refer to the Church (in a very Catholic-sounding phrase) as the “earthly-historical form of the existence of Jesus Christ,” as he put it in the fourth volume of his Church Dogmatics.

But the risen, ascended Christ does not surrender his lordship even to the Body of which he is the Head. The Body is here on earth; the Head is in heaven. The Body functions amidst the ambiguities and temptations of a world in which the powers of darkness have not been finally vanquished; the Head abides in the glory of the Father. What Barth is reacting against here is the temptation to make the Church into an object of faith alongside Christ, a temptation that needs to be resisted on both sides of the confessional divide.

In an earlier writing, an essay titled “Church and Theology,” Barth refers to the fact that in some monastic communities the place of honor at every mealtime in the refectory is properly furnished with tableware, linen, and a chair which is always left unoccupied, just as at the Jewish Passover a chair is reserved for the yet-to-come Elijah. He uses this example to underscore the “not-yet” character of churchly existence in this present age. “God has spoken in his Son, we are now God’s children; but ‘it does not yet appear what we shall be’ (1 John 3:2).” The empty chair at the table reminds the Church, the Bride of Christ, to await the return of her Bridegroom and not to succumb to the heresy of an overly realized eschatology.

It has seemed to some Barth critics that his talk about a Christ who is in some sense remote from the history of his community on earth—“separated from it by an abyss which cannot be bridged”—leaves him vulnerable to a semi-deist concept of Christ. But here, as elsewhere, Barth wants to say both here and there.

In the fourth volume of Church Dogmatics (in the section “The Growth of the Community”), he responds to such critics by emphasizing the other side of this dialectic. What, he asks, “does it mean to speak of there and here, height and depth, near and far, when we speak of the One who is not only the true Son of Man but also the true Son of God, the man who, exalted by the self-humiliation of the divine person to being as man, exists in living fellowship with God?” It means, he continues,

that in the man Jesus who is also the true Son of God, these antitheses, while they remain, are comprehended and controlled; that He has power over them; that He can be here as well as there, in the depth as well as in the height, near as well as remote, and therefore immanent in the communio sanctorum on earth as well as transcendent to it.

The Word’s Creation

Third, the real Church is the creature of the Word and always stands under the authority of Holy Scripture. As a Protestant theologian in the Reformed tradition, Barth understands the Church to be creatura verbi, a “creation of the Word.” He affirms the Reformation principle of sola scriptura in the sense that the prophetic and apostolic witness, which constitutes the content of the Bible, as inspired and illuminated by the Holy Spirit, is the sole basis for the church’s teaching and life.

Fourth, the real Church exists under the Cross and does not seek its own glory. Barth’s writings about the Church can be understood as a protest against every form of ecclesial triumphalism. The Church is always ecclesia in via: the Church on the road, the Church under the Cross. Thus, the real Church has no interest in vaunting itself or in acquiring the accoutrements of worldly power, prestige, or wealth. The Church is God’s shanty, not God’s palace. “The splendor of the church can only consist in its hearing in poverty the Word of the eternally rich God and making that Word heard by men.”

Such a church will be marked more by its fidelity to the gospel than its numerical success or recognition by the media. Fresh from his appearance at the first General Assembly of the World Council of Churches, Barth remarked that “the smallest village church” would be more important than the whole Amsterdam Assembly if its members acknowledge what is said about the Church in question fifty-four of the Heidelberg Catechism:

I believe that, from the beginning to the end of the world, and from among the whole human race, the Son of God, by his Spirit and his Word, gathers, protects, and preserves for himself, in the unity of the true faith, a congregation chosen for eternal life. Moreover, I believe that I am and forever will remain a living member of it eternally.

Fifth, the real Church lives for the sake of the manifestation of God’s grace and glory in its mission and witness to the world. The Church of Jesus Christ was never intended to be a quarantined company detached from the disparities and messiness of history. In a later section of the Church Dogmatics, Barth devotes a lengthy section to “The People of God in World-Occurrence.”

The Church that has been called out from the world, he argues, is the same Church that is also sent back into it. In a sense, the Church might be thought of as an advance party for the kingdom of God; in it, God’s purpose and plan for all humanity is foreshadowed and realized in some measure. “The community lives and grows within the world—an anticipation, a provisional representation, of the sanctification of all men as it has taken place in Him, of the new humanity reconciled with God,” he wrote in “Church and Theology,” later published in Theology and Church.

As the divinely appointed herald of God’s good news to all persons everywhere, the Church is charged with communicating God’s great “Yes” to the world. The Church must not forget God’s “No” either, but it must always lead out with the “Yes.” The “No” we must speak, Barth says, will become audible enough if we occupy ourselves with washing of feet, care for the poor, embrace of the homeless, and other acts of service in Jesus’ name.

Eventful Witnesses

Something should also be said about Barth’s sacramental theology. He never lived to complete his long-awaited study of the Lord’s Supper, and there is very little about this important subject in the many pages of the Church Dogmatics. Barth’s writings on baptism, however, created quite a stir during his own lifetime and have continued to generate further discussion and controversy.

In 1943 Barth published a short treatise, “The Teaching of the Church Regarding Baptism,” in which he called into question the traditional practice of infant baptism. In the final fragment of the Church Dogmatics, he returned to this theme and went even further in rejecting not only infant baptism but the last vestiges of a sacramental understanding of baptism.

Taken together, baptism and the Lord’s Supper are “eventful witnesses to God’s righteous action in Jesus Christ,” as he wrote in Learning Jesus Christ Through the Heidelberg Catechism, a late work. Through these Jesus-appointed ordinances, believers receive the confirmation of their faith and the community receives the confirmation of its origin in Jesus Christ and its life through him.

Barth was fond of quoting a statement from the Augsburg Confession to the effect that the sacraments of the Church are truly efficacious ubi et quando visum est Deo, “where and when God so wills it.” In all of his thinking about the sacraments, Barth wanted “to avoid any suggestion that the action of the Church can be substituted for the action of Christ through the Holy Spirit,” as the theologian John Yocum has put it.

One further word may be said about Barth’s view of the Lord’s Supper. In an interesting article on “Protestantism and Architecture,” Barth suggested that at the center of an Evangelical church building there should be a simple wooden table, slightly elevated, but distinctly different from an altar. Attached to this table, or placed very near it, would be the pulpit and baptismal font. This kind of arrangement, Barth thought, would demonstrate to the congregation the coinherence of Word and sacrament.

In this sense, baptism and the Lord’s Supper are another form of proclamation. No less than the preacher’s sermon, they, too, herald the Word of God; indeed, sacraments are “the visible words of God.” Though he called himself a neo-Zwinglian with reference to baptism and the Lord’s Supper, Barth could nonetheless affirm that these two “eventful witnesses” are not empty signs.

“On the contrary,” he writes in the fourth volume of the Church Dogmatics, “they are full of meaning and power. They are thus the simplest, and yet in their very simplicity the most eloquent, elements in the witness which the community owes to the world, namely, the witness of peace on earth among the men in whom God is well-pleased.”

Evangelical Lessons

What can Evangelicals learn from Karl Barth about the Church? Much, I think, if we are willing to listen.

First, by grounding the Church so completely within the Trinitarian and Christological framework of his theology, Barth presents a very high ecclesiology, one that stands as a corrective to the rugged individualism and “Jesus-in-my-heart-only” piety that marks too much of Evangelical life today.

In the eternal election of Jesus Christ, God chose the Church, the community, to be the Body and Bride of his Son. During his earthly ministry, Jesus summoned individuals one by one to follow him and be his disciples, but he always intended for them to follow him in the company of others. “From the very outset Jesus Christ did not envisage individual followers, disciples and witnesses, but a plurality of such united by him both with himself and with one another.”

Thus, Barth reminds Evangelicals of the corporate character of Christian existence. He teaches us that the Church is not a mere option or add-on to the Christian life, but that it is integral to the eternal purposes of God and indispensable for faithful discipleship.

Second, Barth’s emphasis on the Church as herald or witness resonates strongly with Evangelical perceptions. Historically, Evangelicals have emphasized both the supreme authority of Scripture for the life of faith and the centrality of preaching in the worship of the Church. But the Bible is frequently praised more than used in evangelical worship and programs of evangelism. He never forgot the connection between preaching and theology he had learned as a young pastor in rural Switzerland, and his later sermons to prisoners in the Basel jail show the importance of preaching not only about the Bible, but from it.

Barth’s doctrine of Scripture has been strongly criticized by many Evangelicals, for the disjunction he presents between revelation and the biblical witness seems, despite his best intentions to the contrary, to open the door to the kind of subjectivism and liberalism against which he himself reacted so vigorously. His actual use of the Bible, on the other hand, is from an Evangelical perspective not only extensive but exemplary.

Visible Witness

Third, Barth reminds Evangelicals that baptism and the Lord’s Supper are powerful proclamation events, not mere rituals or optional add-ons to the Christian life. Many Evangelicals will also appreciate what he called his “cautious and respectful de-mythologizing” of sacramentalism, and some, especially those with baptistic convictions, will applaud his disavowal of infant baptism. On the Lord’s Supper, he would have done better to follow Calvin rather than Zwingli, but even here his somewhat minimalist theology can help Evangelicals, many of whom have an even lower view of the Lord’s table than he did.

Barth did refer to the Lord’s Supper as the “common nourishment” of the community of faith. He also, following Calvin, called for its weekly celebration and once said, in Learning Jesus Christ through the Heidelberg Catechism: “Wherever the Supper is celebrated, there Jesus Christ himself is present. And where he is present, there the relation between God’s food and drink and the earthly bread and wine is real.”

Fourth, Barth can help Evangelicals see that faithful witness is more important than “visible results.” Evangelicals have sometimes touted their commitments to mission and evangelism at the expense of a serious interest in ecclesiology. It was Brunner, not Barth, who said that the Church exists for mission just as a fire exists for burning, but this sentiment matches Barth’s understanding as well. He would also remind Evangelicals that the true missionary work of the Church is about more than “drawing large crowds and enjoying success,” and he would surely chide the Evangelical church for its penchant to produce “propaganda on behalf of its own spatial expansion” rather than an unadulterated witness for the gospel. It is hard to imagine his reaction to a few hours of American televangelism.

Finally, Barth can help Evangelicals appropriate the riches of the wider Christian tradition without sacrificing their Reformation heritage. Barth increasingly found genuine Christian fellowship and theological comradeship more easily among his Catholic contemporaries than with his mainline Protestant colleagues. While I would fully expect him to be critical of various joint statements issued by Evangelicals and Catholics in recent years, I also believe that he would rejoice that this conversation is taking place, and that he would encourage its continuation. He would hope, I believe, that such an engagement would—when and where God so wills it—transform both communities in the interest of the one and only gospel of Jesus Christ and for the glory of God alone.

In a short piece Barth wrote shortly before his death, “Starting Out, Turning Around, Confessing,” published in Final Testimonies, he wrote that “the distinctive mark of this one movement of the church” is

taking place or is visible today in the Roman church, or I would prefer to say, the Petrine Catholic and the Evangelical Catholic confessions—for we are Catholic too. For the moment it is surprisingly more visible and even spectacular in the Petrine than in the Evangelical confession. But however that may be, there is this one movement of the one church, in our case of the two confessions.

Uneasy Tension

Going to church with Karl Barth can be good for the Evangelical soul. His ecclesial theology can help Evangelical believers in search of a sturdier doctrine of the Church to move beyond the mere functionalism of “how to” Christianity that American Evangelicals have mastered, and are in danger of being mastered by.

Evangelicals may visit Basel on their way to Canterbury, Wittenberg, Rome, and Constantinople, and perhaps even Schleitheim, knowing that the ultimate goal of such a pilgrimage is none of these but rather that City that hath Foundations. Such an Evangelical ecclesiology will be good not only for Evangelicalism’s soul, but for that of Christianity itself.

Throughout history, the Church has always lived in uneasy tension between the poles of identity and adaptability. The Church can, and often has, shipwrecked on either side of this divide. By emphasizing identity so strongly, the Church can become a holy huddle, cut off from its environing culture and bereft of any sense of urgent mission to the world. Evangelicals have sometimes succumbed to this temptation, resulting in separatism, fundamentalism, and isolation.

Today the greater danger is at the other extreme. In the valid concern for reaching out with the good news of Christ, the Church has taken on board too much of the world’s agenda. It has become too accommodated, even assimilated, to the spirit of the age and in the process is in danger of losing its very soul.

If he were here today, Karl Barth might refer the Evangelical church to these words from his explosive commentary on Romans, originally addressed to a situation perhaps not entirely different from our own:

He who hears the Gospel and proclaims it . . . knows that the church means suffering and not triumph . . . He sees the inadequacy of the church growing apace, not because of its weakness and lack of influence, not because it is out of touch with the world; but, on the contrary, because of the pluck and force of its wholly utilitarian and hedonistic illusions, because of its very great success, and because of the skill with which it trims its sails to the changing fashions of the world.

“The Real Church” was published in The Scottish Journal of Theology in 1950 (pp. 337–353). “Protestantism and Architecture” can be found in Theology Today, July 1962 (http://theologytoday.ptsem.edu/jul1962/v19-2-criticscorner2.htm). Yocum’s comment can be found in his Ecclesial Mediation in Karl Barth.

Timothy George is dean of Beeson Divinity School of Samford University (www.samford.edu) and an executive editor of Christianity Today (www.christianitytoday.com). A different version of this essay is appearing in Karl Barth and Evangelical Theology, edited by Sung Wook Chung, forthcoming from Baker Academic.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor