Pilgrim Johnson

The Author of the 250-Year-Old Dictionary Was a True Man of the Word

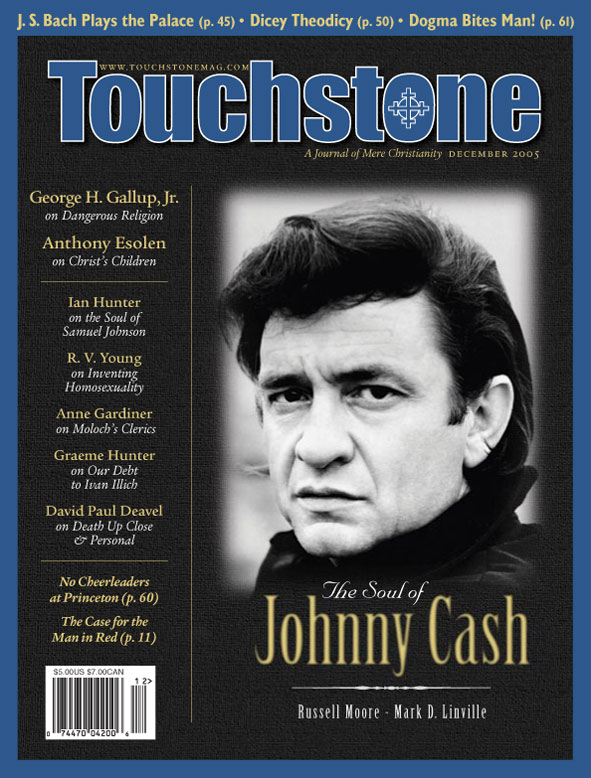

by Ian Hunter

Two and a half centuries ago this year, the first comprehensive Dictionary of the English Language was published. The lexicographer (def. “a writer of dictionaries, a harmless drudge”) was Dr. Samuel Johnson, better known then as an essayist and moralist, and (as is more obvious now than then) a serious Christian in a deistic, even skeptical age.

Nine years earlier, a bookseller named Robert Dodsley asked the 36-year-old Johnson about compiling a dictionary. Dodsley considered it a rebuke to national pride that England lacked anything to equal the great dictionaries of France and Italy, each the product of teams of academics. At first Johnson declined, but when a consortium of London booksellers offered 1,575 guineas (today about $150,000), the chronically impoverished Johnson relented.

The contract called for the dictionary to be delivered in three years. When a friend remonstrated that it took “40 scholars of the French Academy 40 years to complete their Dictionary” (actually, they took 55 years), Johnson replied: “Sir, thus it is: This is the proportion . . . forty times forty is sixteen hundred. As three to sixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman.”

Johnson Patronized

Johnson launched himself on “this vast sea of words” on June 18, 1746, assisted by six amanuenses, five of whom were Scots, in the garret of a house (17 Gough Square) just off Fleet Street. His plan called not just for defining words, but determining their derivations, and illustrating correct usage by apt quotation from the best English authors (Shakespeare, Swift, and Milton predominate in the Dictionary).

For so immense an undertaking it was natural that Johnson should seek a patron. Dodsley suggested Johnson dedicate his much-delayed Plan of the Dictionary—in effect a solicitation for subscribers—to the Earl of Chesterfield, a member of the House of Lords, a former ambassador, and a widely regarded arbiter of public taste. “If any good comes of my addressing it to Lord Chesterfield,” Johnson told a friend, “it will be ascribed to deep policy, when, in fact, it was only an excuse for laziness.”

For nine years Johnson slogged on, his only encouragement from Chesterfield an early gift of ten pounds. Then, on the very eve of publication, Chesterfield wrote two letters to The World, commending the Dictionary and appearing to claim some credit as its patron. This was too much for the proud Johnson, whose stinging reply ranks with the most celebrated letters ever written:

Seven years, my Lord, have now past since I waited in your outward rooms, or was repulsed from your door; during which time I have been pushing on with my work through difficulties, of which it is useless to complain, and have brought it at last, to the verge of publication, without one act of assistance, one word of encouragement, or one smile of favour. Such treatment I did not expect, for I never had a Patron before. . . .

Is not a Patron, my Lord one who looks with unconcern on a man struggling for life in the water, and, when he has reached ground, encumbers him with help? The notice which you have been pleased to take of my labours, had it been early, had been kind; but it has been delayed till I am indifferent and cannot enjoy it; till I am solitary, and cannot impart it; till I am known, and do not want it.

Johnson had few illusions about the reception of his Dictionary. In the preface he wrote: “Every other author may aspire to praise; the lexicographer can only hope to escape reproach.” As it turned out, Johnson’s work was to be considered authoritative, at least until James Murray’s great Oxford English Dictionary appeared over a century later.

Personal Dictionary

Johnson’s Dictionary differs from today’s dictionaries in several respects, not least in its personality. It is frequently acerbic. “Cant,” for example, is “high sounding language unsupported by dignity of thought.” His definition of “excise” will, at least for Canadians, seem a model of concision: “a hateful tax levied upon commodities, and adjudged not by the common judges of property, but by wretches hired by those to whom excise is paid.”

And it is often funny. Johnson defined “pension” as “an allowance made to anyone without an equivalent,” then elaborated: “In England it is understood to mean pay given to a state hireling for treason to his country.” He famously defined “oats” as: “A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.”

Johnson made no claim to infallibility. He defined “pastern” as “the knee of a horse” and when challenged by a lady in Plymouth to explain why, replied, “Ignorance, madam, pure ignorance.”

Of course, the Dictionary has dated since 1755. Indeed archaisms are half its charm. It is full of lovely, long-lost words, like “clapperclaw” (to scold), “ninnyhammer” (a simpleton), and “wamble” (to roll with nausea).

Sometimes Johnson’s definitions were more abstruse and impenetrable than the word being defined; for example, for “network,” Johnson gave: “anything reticulated or decussated, at equal distances, with interstices between the intersections.”

Johnson concluded his Preface with a note of stoic resignation, a note sounded frequently in his late writings. The Dictionary

was written with little assistance of the learned, and without patronage of the great; not in the soft obscurities of retirement, or under the shelter of academic bowers, but amidst inconvenience and distraction, in sickness and in sorrow . . . if our language is not here fully displayed, I have only failed in an attempt which no human powers have hitherto completed. . . . I have protracted my work till most of those I wished to please have sunk into the grave, and success and miscarriage are empty sounds: therefore I dismiss it with frigid tranquility, having little to fear or hope from censure or from praise.

Humbling words, these, particularly given the magnitude of Johnson’s achievement: more than 40,000 words defined, etymologies provided, usage illustrated; two volumes, 2,300 pages; original price four pounds, ten shillings. By the end of the project, the tempers of everyone were frayed: “Thank God I now have done with him,” bookseller Andrew Millar said when the last, hand-corrected proof sheets arrived from Johnson. When informed of Millar’s comment, Johnson said: “I am glad he thanks God for anything.”

From Birth to London

Samuel Johnson was born in September 1709 in the cathedral town of Lichfield in Staffordshire. He was the first of two sons of an impecunious bookseller, Michael Johnson (then 52), and his wife Sarah (40). The birth was difficult. His parents doubted he would survive and arranged to have him christened that night in the room where he was born.

Sarah was unable adequately to nurse her son, and a wet nurse was contracted, with disastrous results: Sam developed a tubercular infection of the lymph glands, then known as “scrofula” (def. “a deprivation of the humours of the body which breaks out in sores, commonly called the king’s evil”). His vision deteriorated so badly that, when he was two, his mother took him to be “touched” by the queen at St. James’s Palace in London. These were just about the last days when people believed in the efficacy of “royal touch” as a cure.

So prodigious was young Sam’s intellect and recall that his parents frequently made him perform for visitors, a showing-off that he hated. Years later Johnson told his friend Mrs. Thrale: “This is the great misery of late marriages, the unhappy produce of them becomes the plaything of dotage . . . teased with awkward fondness . . . forced to divert a company, who at last go away complaining of their disagreeable entertainment.”

In 1728 Sam left for Pembroke College, Oxford. Here he passed four terms composing poetry, arguing, studying, and cutting lectures. When his tutor fined him for sliding in Christchurch meadow when he should have been in class, Johnson replied: “Sir, you have sconced me twopence for non-attendance at a lecture not worth a penny.”

It was at Oxford that Johnson first read William Law’s A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1726). He later told his biographer James Boswell: “I took up [ A Serious Call] expecting to find it a dull book, as such books generally are, and perhaps to laugh at it. But I found Law was quite an overmatch for me; this was the first occasion of my thinking in earnest of religion.” It was “the finest piece of hortatory theology in any language.” In the Dictionary, Johnson quotes Law 196 times.

After his attenuated studies at Oxford, Johnson spent seven years as a schoolmaster, acquiring in the process a wife, Elizabeth Porter, twenty years his senior, a woman of scant wealth and less beauty. Yet Johnson remained devoted to his “Tetty” until her death in 1752, and faithful to her memory ever after; the tenderest, and often the most self-lacerating, of his prayers were composed on significant anniversaries, especially on the anniversary of her death.

Johnson the Hack

Finally Johnson resolved “to become an author by profession.” With his sometime pupil, David Garrick, who would rise to fame as the most celebrated actor of his generation, he set out in March 1737 to walk from Lichfield to London. Johnson’s first paid (albeit meagerly) journalistic employment was on the Gentleman’s Magazine, to which he contributed odes, epigrams, obituaries, book reviews, and, under the title “Debates in the Senate of Lilliput,” what were supposed to be records of parliamentary debate.

Johnson, however, seldom went near the House of Commons and, in any case, reporting of parliamentary proceedings was then a crime. Instead, Johnson relied upon such vagrant reports as might reach him and upon his own imagination. So lucid were the speeches he composed that politicians to whom they were attributed delighted to adopt them as their own. Only once did Johnson reveal the truth. When he heard dinner guests praising a recent speech of William Pitt’s, and going so far as to compare Pitt’s eloquence to Demosthenes’, Johnson muttered: “That speech I wrote in a garret.”

Years of poverty followed. All the schemes, heartbreak, and failures of would-be authors were familiar. “Writers who lived men knew not how, and died obscure, men marked not when.” When he came to compile the Dictionary, Johnson needed look no further than his own experience as a self-described “Grub Street hack” to define “Grub Street”: “A street . . . much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries, and temporary poems; whence any mean production is called Grub Street.”

It was Johnson’s essays, first in The Rambler in the early 1750s (whose authorship Johnson initially hoped to keep anonymous lest his own life disgrace what he wrote), then in The Adventurer and The Idler, which built his reputation as moralist and sage. After the Dictionary appeared in 1755, his stature as England’s pre-eminent man of letters was unassailable. King George III granted him a pension of 300 pounds annually.

By the time an impetuous young (22) Scottish lawyer, James Boswell, appeared on the London literary scene in the year 1762, Johnson, now 53, was a celebrated literary lion. It was at a bookshop in Russell Street that Boswell lay in wait to meet Johnson.

Boswell, aware of Johnson’s supposed antipathy to Scots, begged the owner not to disclose his origins. But not to be deprived of an opportunity for sport, he introduced Boswell as “a young gentleman from Scotland.” “I do indeed come from Scotland, Sir,” Boswell said, “but I cannot help it.” “That, sir,” replied Johnson “is what I find a great many of your countrymen cannot help.”

Boswell was crestfallen, but a friendship began that day that would forever change the lives of both men. “Give me your hand. I have taken a liking to you,” Johnson greeted Boswell a few days later. Boswell devoted the rest of his life to collecting and assembling material about Johnson, then to the writing, publication, and revising of what became (in the modern sense) the first, and arguably the greatest, biography in the English language: The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D, first published on May 16, 1791, seven years after Johnson’s death.

The flaw in Boswell’s Life is his over-reliance on Johnson’s later years. Johnson’s last eight years occupy three-quarters of the Life. It tends also to over-emphasize the irascible “John Bull” figure, the debater who tossed and gored opponents, the adversary who “talked for victory, who gave no quarter and expected none.” This obscures the deeper, religious Samuel Johnson.

Religious Johnson

The religious Samuel Johnson may be thought of as an equivalent of G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis in the mind and style of the eighteenth century. He may strike many contemporary readers as moralistic, but even if so, he offered great insight into the life of the Christian in this world, as a few quotations may show.

As C. S. Lewis wrote a friend, “I find Johnson very bracing when in my slack, self-pitying mood.” Describing his effect as a writer, Lewis noted that “the amazing thing is his power of stating platitudes—or what in any one else would be platitudes—so that we really believe them at last and realize their importance.” G. K. Chesterton, who both resembled and admired him (and wrote a play about him called The Judgment of Dr. Johnson), warned the readers of “this splendidly sane man”: “do not be in haste to call a comment antiquated; you never know when it will be new.”

Johnson’s explanation of God’s forgiveness is made in the moralistic way, but effectively still. It was, he wrote in The Rambler, “the first and fundamental truth of religion.”

For though the knowledge of his existence is the origin of philosophy, yet, without the belief of his mercy, it would have little influence upon our moral conduct. There could be no prospect of enjoying the protection or regard of him whom the least deviation from rectitude made inexorable for ever; and every man would naturally withdraw his thoughts from the contemplation of a creator, whom he must consider as a governor too pure to be pleased, and too severe to be pacified; as an enemy infinitely wise and infinitely powerful, whom he could neither deceive, escape, nor resist.

Johnson was concerned with death to a degree that a materialistic age like ours (and his) may find morbid, but yet a version of our Lord’s own warnings, put in the terms of his time. “The great incentive to virtue is the reflection that we must die,” he wrote in an essay for The Rambler, and suggested that

Every funeral may justly be considered as a summons to prepare for that state into which it shows us that we must some time enter; and the summons is more loud and piercing as the event of which it warns us is at less distance. To neglect at any time preparation for death is to sleep on our post at a siege; but to omit it in old age is to sleep at an attack.

On a more practical level, he commented with sense and wit on the Quaker rejection of fancy dress:

Oh, let us not be found when our Master calls us, ripping the lace off our waistcoats, but the spirit of our contention from our souls and our tongues! Let us all conform in outward customs, which are of no consequence, to the manners of those whom we live among, and despise such paltry distinctions. Alas, Sir (continued he), a man who cannot get to heaven in a green coat, will not find his way thither the sooner in a grey one.

Much more could be said to illustrate Johnson’s spiritual insight and wisdom. Boswell’s book abounds with it, in transcriptions of Johnson’s conversation and in literally hundreds of witty and often insightful apothegms. Here are a few, taken almost at random from the Life of Johnson. On men and marriage: “Marriage is the best state for a man in general; and every man is a worse man, in proportion as he is unfit for the married state.”

And: “To find a substitution for violated morality was the leading feature in all perversions of religion.” And also: “Keep always in your mind, that, with due submission to Providence, a man of genius has been seldom ruined but by himself.” And finally, he wrote of pride that it is “a corruption that seems almost originally ingrafted in our nature. . . . It mingles with all our other vices, and without the most constant and anxious care, will mingle also with our virtues.”

Johnson Unconsoled

Johnson never derived much consolation from his Christian convictions. In his journals, he often recorded the hope that he might recover from “the general Disease of my life.” His 1761 Easter Eve Journal entry is typical: “I have led a life so dissipated and useless, and my terrours and perplexities have so much increased, that I am under great depression. . . . Almighty and merciful Father look down upon my misery with pity.”

Three years later, on Easter 1764, he records: “Let me not be created to misery. . . . Deliver me from the distresses of vain terrour.” And again two years later: “O God! . . . Grant that I may no longer be disturbed with doubts and harassed with vain terrours.”

There are possible explanations for Johnson’s religious melancholy. On a late (1784) visit to an Oxford friend, Dr. Adams, Boswell records how he “with a look of horror” acknowledged that he was “much oppressed by the fear of death.” When Adams remonstrated that God was “infinitely good” and therefore to be trusted, Johnson replied: “I cannot be sure that I have fulfilled the conditions in which salvation is granted; I am afraid that I may be one of those who shall be damned (looking dismal).” Adams asked him what he meant by “damned.” Johnson replied, “(passionately and loudly): Sent to hell, Sir, and punished everlastingly.” This exchange occurred within six months of Johnson’s death.

Also, the text in Luke 12:48, “To whom much is given, of him much will be required,” haunted Johnson. He was not falsely modest; he knew his gifts were great, and he feared that, in any divine accounting, his achievements would be found incommensurable. Mrs. Thrale, whom Johnson loved (and near the end of his life perhaps hoped to marry), wrote: “He knew how much he had been given, and filled his mind with fancies of how much would be required, until his impressed imagination was often disturbed.”

To the fears that preyed upon his imagination—fear of losing his faculties, fear of being alone, fear of dying—Johnson proposed to “confirm myself in the conviction of the truths of religion.” To accomplish this he was forever writing resolutions: “To rise by eight or earlier” and “To form a plan for the Regulation of my daily life” are typical.

Yet it should be remembered that Johnson spoke as he did from a deep belief in divine mercy as well as justice. Prayer he considered “a reposal of myself upon God, and a resignation of all into his holy hand.” In one of his Rambler essays, speaking in the voice of a hermit, he described at length and in detail (and with an insight similar to The Screwtape Letters) the course of the sinful life. Yet he ended the passage with a call

not to despair, but . . . remember, that though the day is past, and their strength is wasted, there yet remains one effort to be made; that reformation is never hopeless, nor sincere endeavours ever unassisted; that the wanderer may at length return after all his errours, and that he who implores strength and courage from above shall find danger and difficulty give way before him. Go now, my son, to thy repose, commit thyself to the care of Omnipotence, and when the morning calls again to toil, begin anew thy journey and thy life.

A Church of England Man

Johnson often upbraided himself for failing at “publick worship,” but the banal homilies on offer he found nearly beyond endurance. He once told Boswell that “he went more frequently to church when there were prayers only than when there was also a sermon.” And he told a friend: “I am convinced I ought to be present at divine service more frequently than I am; but the provocations given by ignorant and affected preachers too often disturb the mental calm which otherwise would succeed to prayer.”

Johnson was suspicious of solitary worship, as he was of any individualism or cultic enthusiasm. He was a Church of England adherent, steeped in and devoted to the liturgical treasures of Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer (“the genuine offspring of piety and prayer”).

“To be of no church is dangerous,” he maintained. “Religion, of which the rewards are distant and which is animated only by Faith and Hope, will glide by degrees out of the mind unless it be invigorated and re-impressed by external ordinances, by stated calls to worship, and the salutary influence of example.” The solitary believer, he said to Mrs. Thrale, is “probably superstitious, and possibly mad.”

When informed of a young woman who had abandoned the Church of England to become a Quaker, Johnson was unusually rude: “I hate the arrogance of a young wench who sets herself up for a judge on theological points, and deserts the religion in whose bosom she was nurtured.” When his interlocutor insisted that the young woman’s belief was sincere, and this was demonstrated because she had sacrificed a “noble fortune” for her beliefs, Johnson growled: “Madam, Madam, I have never taught myself to consider that the association of folly can extenuate guilt.”

The Pilgrim

The most perceptive of Johnson’s modern biographers, Walter Jackson Bate, noted that Johnson lived daily with “a stark existential dread” that seems almost to belie his religious beliefs. When a friend pointed out that Christ’s death and resurrection provides “evidence, good evidence” of immortality, Johnson gloomily muttered: “I like to have more.” Arthur Murphy told Boswell that he had often heard Johnson saying aloud these lines from Measure for Measure: “Ay, but to die and go we know not where;/ To lie in cold obstruction and to rot.”

Did Johnson ever achieve any spiritual serenity? This is a difficult question. Since he recorded his prayers and meditations, there is an ample evidentiary archive, but the evidence is inconclusive. As early as 1765 he resolved, as noted already, “to consider the act of prayer as a reposal of myself upon God, and a resignation of all into his holy hand.” Yet even his last prayer, composed the very day he died (December 13, 1784), refers to “my imperfect repentance” and seeks pardon for “the multitude of my offences.”

Boswell, however, relates the story of his “tranquil” death in this way:

The Doctor, from the time that he was certain his death was near, appeared to be perfectly resigned, was seldom or never fretful or out of temper, and often said to his faithful servant, who gave me this account, “Attend, Francis, to the salvation of our soul, which is the object of greatest importance”: he also explained to him passages in the scripture, and seemed to have pleasure in talking upon religious subjects.

Charity, we are told, covers a multitude of sins, and, despite his occasional outbursts, Johnson was the most charitable of men. A friend wrote: “He frequently gave all his silver to the poor, who watched him, between his house and the tavern where he dined.” Mrs. Thrale said that he never spent money on himself, but gave all he had away.

Johnson’s house was a home to indigents, many of whom—Dr. Levet, the slum physician; Anna Williams, the blind poetess; and Frank Barber, a former slave—lived on his hospitality for years. Johnson couldn’t bear to see children sleeping in the streets, and pressed coins into their hands when he passed. When he was asked why he gave money to beggars, Johnson replied only: “Why, Madam, to enable them to beg on.”

Johnson loved John Bunyan’s classic, The Pilgrim’s Progress (the phrase “the pilgrimage of life” occurs in both his essays and sermons). It was one of only three books, he maintained, that readers wished were longer ( Gulliver’s Travels and Robinson Crusoe were the others). And perhaps Johnson is best understood as a pilgrim, on a solitary, difficult trek, like Bunyan’s pilgrim, from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City. In the Dictionary Johnson had defined “pilgrim” as “a wanderer, particularly one who travels on a religious account.”

All his life, Johnson traveled on a religious account, and pilgrims beyond number have since drawn upon his account without diminishing it.

Readers interested in reading quotes from Johnson arranged by topic should see www.samueljohnson.com/topics.html.

The Marital Realist

by David Mills

Samuel Johnson spoke often of marriage, and with a realism expressing a shrewd spiritual insight into the facts of human life, which are often the facts many of us do not see. In The Rambler, he warns of married men and women who regret their marriages, or at least speak as if they do, not realizing that their feelings may have little to do with their marriages but much with the natural course of life. They “relate the happiness of their earlier years, blame the folly and rashness of their own choice, and warn those whom they see coming into the world against the same precipitance and infatuation.”

Then he offers an insight that is obvious when you hear it said, but not until then.

But it is to be remembered, that the days which they so much wish to call back, are the days not only of celibacy [he speaks of a different time than ours] but of youth, the days of novelty and improvement, of ardour and of hope, of health and vigour of body, of gaiety and lightness of heart. It is not easy to surround life with any circumstances in which youth will not be delightful; and I am afraid that, whether married or unmarried, we shall find the vesture of terrestrial existence more heavy and cumbrous the longer it is worn.

The same is true of his analysis of marital arguments, also from The Rambler. Such arguments, bitter as they often are, might make us think

that almost every house was infested with perverseness or oppression beyond human sufferance, did we not know upon how small occasions some minds burst into lamentations and reproaches, and how naturally every animal revenges his pain upon those who happen to be near, without any nice examination of its cause. We are always willing to fancy ourselves within a little of happiness, and when, with repeated efforts, we cannot reach it, persuade ourselves that it is intercepted by an ill-paired mate, since, if we could find any other obstacle, it would be our own fault that it was not removed.

Johnson’s realism was not cynicism, however, and takes some surprising turns. In one long passage from The Rambler, he listed all the foolish reasons people marry someone to whom they are neither suited nor agreeable, such as “the avaricious and crafty taking companions to their tables and their beds, without any inquiry but after farms and money; or the giddy and thoughtless uniting themselves for life to those whom they have only seen by the light of tapers at a ball.”

But then he notes: “I am not so much inclined to wonder that marriage is sometimes unhappy, as that it appears so little loaded with calamity; and cannot but conclude that society has something in itself eminently agreeable to human nature, when I find its pleasures so great that even the ill choice of a companion can hardly overbalance them.” This is less true now, when divorce is so easy, but there is a truth in it that gives hope.

Johnson’s realism was indeed realistic, and in a way we modern men, tainted by romanticism as we are, may find disturbing. He understood a good marriage to be a matter of the will to love, and not the feelings so highly valued even in his day—feelings he knew, as he makes clear many times, depend upon features like beauty that pass away even in this life.

It depends upon virtue. Marriage, he wrote in the Rambler, “is the strictest tie of perpetual friendship, and there can be no friendship without confidence, and no confidence without integrity; and that he must expect to be wretched, who pays to beauty, riches, or politeness, that regard which only virtue and piety can claim.”

He once suggested to his friend James Boswell that “marriages would in general be as happy, and often more so, if they were all made by the Lord Chancellor, upon a due consideration of characters and circumstances, without the parties having any choice in the matter.”

And thus, as Boswell records in his Life of Johnson, when asked, “Do you not suppose that there are fifty women in the world, with any one of whom a man may be as happy, as with any one woman in particular?”, Johnson answered, “Ay, Sir, fifty thousand.”

The romantic who wants a soul mate, and indeed thinks he deserves one, and does not realize that what he thinks makes a soul mate may simply be the fetching way she tilts her head or the shape of her torso, snarls or scoffs. The man who wants a Christian marriage listens.

A Voice of All FleshFor Johnson is immortal in a more solemn sense than that of the common laurel. He is as immortal as immortality. The world will always return to him, almost as it returns to Aristotle; because he also judged all things with a gigantic and detached good sense. One of the bravest men ever born, he was nowhere more devoid of fear than when he confessed the fear of death.

There he is but the mighty voice of all flesh; heroic because timid. [On his deathbed] there was no part of the sociable and literary Johnson, but of the solitary and immortal one. I will not say that he died alone with God, for each of us will do that; but he did in a doubtful and changing world, what in securer civilizations the saints have done.

He detached himself from time as in an ecstasy of impartiality; and saw the ages with an equal eye. He was not merely alone with God; he even shared the loneliness of God, which is love.

— G. K. Chesterton

Ian Hunter is Professor Emeritus in the Faculty of Law at the University of Western Ontario. He is the author of biographies of Robert Burns, Hesketh Pearson, and Malcolm Muggeridge.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on biographical from the online archives

more from the online archives

27.3—May/June 2014

Religious Freedom & Why It Matters

Working in the Spirit of John Leland by Robert P. George

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor