Pilgrims Giving Thanks

Cherishing the America We Were Not Made For

This Thanksgiving, the Wall Street Journal will reprint, as it has every year for more than four decades, an account of the Pilgrims, those zealous and indomitable English separatists who left their refuge in Holland to settle in what was truly, for them, a New World. The text in question comes from Nathaniel Morton’s 1669 book, New England’s Memorial, and Morton’s title is still highly appropriate today, even if we live in a time when the words “New England” have come to elicit a more complicated set of associations, so that the title is likely to be read in a double-edged way.

I will not duplicate the Journal’s efforts here, except to note that Morton’s understated yet harrowing account is well worth rereading every year. For one thing, it offers powerful testimony to the courage and resolution required of those involved in this undertaking.

But just as importantly, it serves as a reminder of the remarkable lengths to which these forebears were willing to go, to establish a Christian way of life for themselves and their offspring. It is right that we should regularly remember them, and give thanks for them, as remarkable presences in that cloud of witnesses whose voices and examples help us orient ourselves.

Our Puritan Teachers

What can we learn from them? To begin with, some of the weight and cost of being “pilgrims and strangers here below.” The Pilgrims “looked not much on [earthly] things,” including the comforts they had enjoyed in the “goodly and pleasant city of Leyden,” but instead “lifted up their eyes to Heaven, their dearest country, where God hath prepared for them a city.”

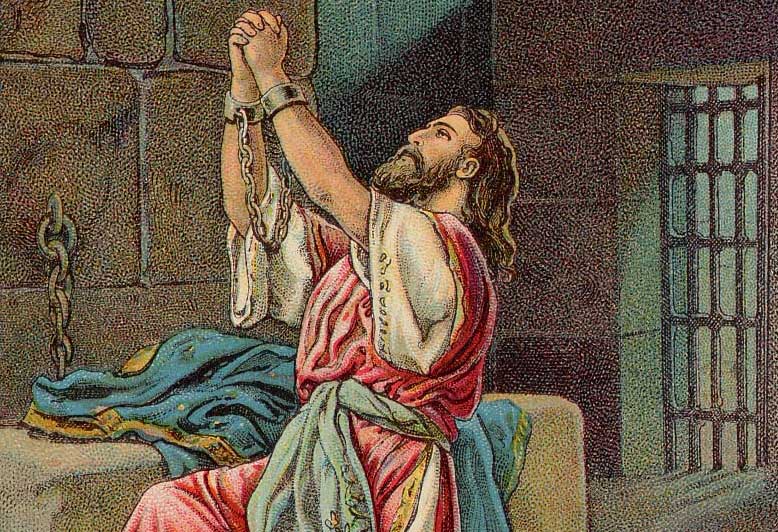

I am especially riveted by Morton’s description of the arriving Pilgrims’ predicament. After a long and perilous Atlantic crossing, they found themselves confronting a cruel and unforgiving winter landscape, more severe than anything they had ever known, with “no friends to welcome them, no inns to entertain or refresh them, no houses, or much less towns, to repair unto to seek for succour,” only “a hideous and desolate wilderness.”

And when they looked behind them, they saw the “mighty ocean which they had passed, and was now as a main bar or gulf to separate them from all the civil parts of the world.” Whatever way “they turned their eyes (save upward to Heaven) they could have but little solace or content in respect of any outward object.”

The scene inspires awe. How did they manage? It is at such points that all strictly material explanations of history fail and fall mute. The Pilgrims, and the Puritans who followed them, sustained themselves with the certain conviction that they were reenacting, through the gritty determination of their own lives, the primordial pattern of biblical displacement and exile and restoration.

Those stories were the very warp and woof of their existence, the meat and drink that kept them going when the entire universe of “outward objects” could offer nothing encouraging or consoling or sustaining, only a wild and mocking barrenness. Without that biblical pattern that was the source of meaning for this endeavor, the great Puritan migration to North America would never have occurred, and certainly never have been as successful as it was.

And we would consequently have been a very different people. It is because of them that those stories, including their own story, are part of the warp and woof of this nation too. Critics of the concept of “Christian America” are right, of course, albeit in a more limited way than they imagine. The founding of this nation can’t be reduced to religious tenets and motives.

But it cannot be understood, then or now, without frequent recourse to them. A group of people who knew themselves to be “pilgrims and strangers here below” from the very outset of their enterprise thereby established a safeguard against the tendency to confuse the nation with the Kingdom. Let us be thankful, this Thanksgiving, that this insight, among so much else that they bequeathed us, has not been lost.

Prophetic Contempt

It is now fashionable among certain Christians to demonstrate their “prophetic” devotion to Christ by expressing their contempt for the American nation-state and its works, in favor of identifying American Christians as “a peculiar people” or “resident aliens.” I will admit to having some occasional sympathy for such sentiments, particularly when I contemplate some of the unlovely features of our culture. And such critics do us all an important service, if only in reminding Christians that they are first and foremost citizens of heaven.

But I think the harshness of their judgments too often misses the mark, and falls short of Christian maturity. They can speak with a glib dismissiveness and sloganeering that reflects the feckless and juvenile tone of today’s political partisanship, adopting their judgments without a sense of their weight and their cost.

Normally one ought to try to overlook the way something is said, in the interest of discerning the substance being conveyed, however imperfectly, but tone is sometimes inseparable from substance, and even good ideas can be vitiated by being adopted and proclaimed wrongly. A self-indulgently expressed critique may be worse than no critique at all, precisely because it serves to undermine its own cause. It may, like a weakened bacterial strain, only strengthen the immune system it would challenge.

Peculiar Snobs

There is all the difference in the world between a cosmopolitanism that builds upon, and transcends (sometimes at great personal expense), one’s more provincial and local loyalties, and a cosmopolitanism that never had any such loyalties to begin with, a cosmopolitanism that offers itself as a perpetual superior pose, a lifelong adolescent revenge against the village by the village expatriate.

The latter form of cosmopolitanism is the stock in trade of the secular academy, as close to an established faith as one can find there. Yet it has its appeal to certain Christians too, and hence its dangers. Calling ourselves “a peculiar people” or “resident aliens” should not become a religiously sanctioned way of giving the finger to our neighbors.

One of these Christians’ most overused words is “idolatry.” It should be used far more sparingly. Not every powerful earthly attachment is a form of idolatry.

On the contrary. The Incarnation demands that we cherish what we have, what we have been given, here and now—the day-old bread on our table, the tangled families in which we find ourselves, the often-exasperating work of our hands, the disappointing churches in which we worship—even as we are called to remember, and live in the light of, what is beyond them. We are called to cherish what we have, as a foretaste of what we have been promised.

The virtues of patriotism are secondary but real—as real and as imperative as the virtues of any of our proper loyalties, short of those to God himself. We should be thankful for the peerless gift of this rich and abundant land. With all its faults, it has been a refuge for all humanity: an island of prosperity and order and democracy in a cruel and violent world, and a place where the most vital of all liberties, the freedom to worship God in spirit and truth, has been cherished and enshrined in our fundamental institutions.

We constantly fail to appreciate the magnitude of this legacy—and the responsibilities entailed in it. We should live in gratitude and faithfulness to it, even as we build upon it in our own ways. We should strive to be worthy of our forebears’ hopes, their dreams, their sacrifices, and their love. We should pray for the strength and wisdom and discipline to be good stewards of this gift. And yes, we are obliged to improve and purify and preserve it, so that the generations to come will also have reason to be thankful that we were here.

Not Made for America

Yet even as we give thanks for our nation, the example of the Pilgrims reminds us that this beautiful place is not our home. That we were made not for it, or for any other earthly nation, but for God alone.

That even this great nation, like all things here below, is imperfect, and will perish someday. That even as we make our homes, plant our gardens, stock our kitchens, and raise our families here, there will come a time when those families are no more, when even the least trace of our yet-unborn children and grandchildren will have vanished, our houses will be torn down, and every token of the earth’s grace and beauty will have decayed into dust and been scattered in the air. That this city on a hill is, like every earthly city, not a city for us to abide in.

Thanksgiving is a time to love our country for the right reasons. It is, on the simplest plane, where God has placed us. That alone makes it a gift we did not deserve, and makes love of country something deeply akin to neighbor-love.

But there are also specific reasons to love it. It is a nation that does not—yet—put Caesar in God’s place, and is still—for now—a land where the knowledge of God’s Word and kingdom has been given a special protection. Indeed, it has been a bulwark to pilgrims and seekers through the years, and remains so today, despite many threatening forces.

We are fortunate to be citizens of a nation founded, in part, by pilgrims, a paradox that in some sense captures the essence of the matter. Long may it prosper, and may we always have hearts capable of gratitude for what we have been given. But may we also always be pilgrims, who seek God’s kingdom first.

Wilfred M. McClay holds the SunTrust Chair of Humanities at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, and is the author of The Masterless: Self and Society in Modern America (North Carolina) and A Student's Guide to U.S. History (ISI Books). He is a member of the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on America from the online archives

more from the online archives

35.4—Jul/Aug 2022

The Death Rattle of a Tradition

Contemporary Catholic Thinking on the Question of War by Andrew Latham

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor