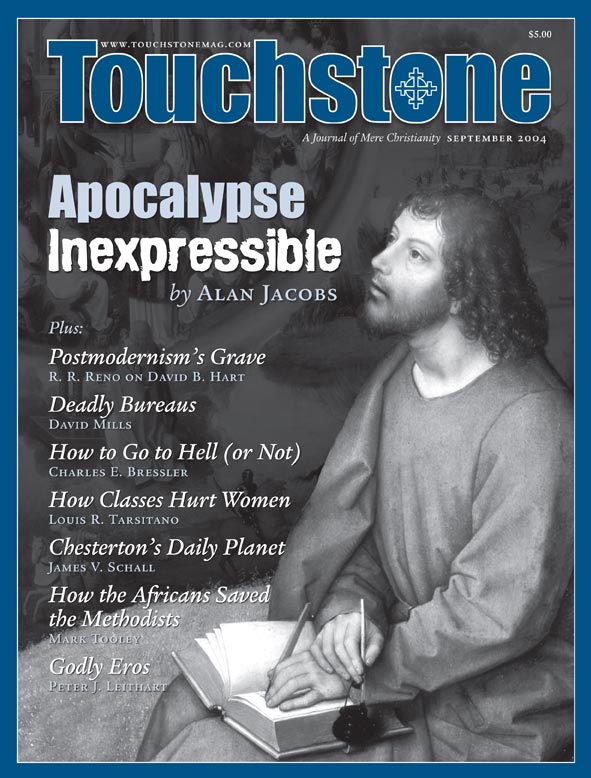

Feature

The Inexpressible Apocalypse

Maybe St. John Did, After All, Write the Final Word

I begin with a cartoon by the great Roz Chast that appeared in The New Yorker some years ago. It bears a headline: “The Four Press Agents of the Apocalypse.” I can no longer remember what the first three press agents say, but the words of the fourth I recall perfectly: “It’s a-comin’, and it’s gonna be big.”

We Puff or Sneer

It is always painful, I know, to be forced to endure the unpacking of a joke, but please bear with me: this one, I think, is worth unpacking. The idea behind the joke, of course, is that press agents devote their lives to making small things seem big, to blowing things up—“puffing,” as the ad-world jargon has it.

“Puff Graham,” the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst commanded his subordinates half-a-century ago, once he saw the charisma of the ambitious young evangelist—little imagining that long after people had forgotten Mr. Hearst (save, perhaps, as the model for Orson Welles’s Charles Foster Kane), Billy Graham would still be famous. Sometimes what the press agents puff can inflate beyond all expectation, and sometimes, believe it or not, there arise persons or events vaster than our powers of inflation, denigration, or praise.

Some years ago John Updike wrote, “We cannot imagine a Second Coming that would not be cut down to size by the televised evening news, or a Last Judgment not subject to pages of holier-than-Thou second-guessing in The New York Review of Books.” I must admit that when I reflect on the Last Judgment, I never wonder what the New York Review of Books would think about it. Presumably they would commission Garry Wills to write a long essay demonstrating how God had, through a combination of administrative mismanagement and mendacity, bungled the whole affair, which in any case should have been left to an ad hoc bipartisan task force overseen by a major activist/intellectual—Hillary Clinton, say.

In any event, if the cartoon mocks our inability to imagine events larger than our powers of puffery, Updike suggests our inability to imagine events beyond our powers of sneering diminution. For Updike, this deficiency of imagination stems from a governing fact of contemporary cultural life: “Our brains,” he writes, “are no longer conditioned by reverence and awe.” One might extend that remark by saying that our brains are conditioned by irreverence and a resistance to awe.

But there is a more fundamental point to be made than either Chast or Updike indicates: It is, simply, that the Apocalypse cannot be narrated. Apocalypse in the true sense is the end of history, and the end of history is the end of narrative; it is beyond our powers of storytelling because it is beyond story itself. Having said this, I may well have made the only point I am capable of making on this subject. But that is a question that I will return to near the end.

The validity of my claim that the Apocalypse cannot be narrated may only be tested once we are sure what we mean by “apocalypse.” It seems to me that, when that term is employed in literary discourse, it is used in two different ways, with different degrees of legitimacy and usefulness. It is used both for stories that depict the end of the world (these are usually secular) and for those (usually Christian) that depict the events leading to the Last Trump. The second will be our main subject.

The End of the World

First, we have depictions (usually uninformed by Christian belief) of the “end of the world,” by which is usually meant either the end of humanity or the end of life on this planet. Thus Neville Shute’s On the Beach or Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, to take a couple of famous examples. Narrative fiction is the typical, though not the exclusive, venue for such stories. (It is interesting to note that this kind of book is a staple of high-school reading lists.)

But such stories only occasionally deal with the actual arrival of The End. Instead, they tend to show that end narrowly averted, as in Michael Chabon’s wonderful novel for young people Summerland, or to show the new and fragmentary human society surviving the wreckage of the old.

The latter sort of story can even offer a kind of American optimism, the myth of Starting Over and Getting It Right. I would not call A Canticle for Leibowitz an optimistic work by any means, but there is the possibility of a certain sober hopefulness in the way it concludes, with human beings leaving this irredeemably broken world to begin anew elsewhere. It offers only the possibility of such hopefulness, though—one is equally free to imagine us doing as much damage to our new world as we did to this, our original habitation.

There are still bleaker visions. Two centuries ago Lord Byron wrote an astonishing poem, “Darkness,” that portrays something like the death of the universe:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguished, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

For a time some creatures manage to survive in this emptiness, but soon enough no life remains:

The world was void,

The populous and the powerful was a lump,

Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless—

A lump of death—a chaos of hard clay.

The rivers, lakes, and ocean all stood still,

And nothing stirred within their silent depths;

Ships sailorless lay rotting on the sea,

And their masts fell down piecemeal; as they dropped

They slept on the abyss without a surge—

The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The Moon, their mistress, had expired before;

The winds were withered in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perished! Darkness had no need

Of aid from them—She was the Universe!

It is an utterly chilling vision—even in A Canticle for Leibowitz and On the Beach some life remains on the ravaged earth, if not human life—but I would argue that even Byron’s depiction of ultimate horror is not truly apocalyptic, for at the heart of apocalypse is (as the word’s origin teaches) the idea of revelation, of unveiling. These works describe catastrophes, even what for the human race is the greatest of catastrophes—its annihilation—but in them is no element of disclosure. Nothing is unveiled.

They do not reveal anything to us we do not already know: That we are morally and now technologically capable of destroying ourselves and much of our world is hardly news. Such tales describe not the culmination, the transformation, the apotheosis, or the demonization of history, but simply its trickling into nothingness—history on its worst day. It is quite sad if you happen to be part of the story, just as it is quite sad when a business you work for closes its doors for the last time, but such an ending is not, strictly speaking, significant.

The Last Trump

The second use of the word describes depictions (usually Christian) of the events leading up to the Last Trump: Such stories tend to deal not with the End itself but with dramatic events that point towards it, that indicate its imminent arrival. In these, theological positions have literary consequences, because the way one conceives the nature of the End Times affects the way one tells the story. In particular, as we will see, certain kinds of stories emerge from Protestant dispensationalist thought that do not, or do not easily, consort with Catholic eschatology. And in the limits of these stories we see, I think, the reason apocalypse cannot be narrated.

In this second category would be Michael O’Brien’s Father Elijah, a Catholic work, and Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins’s dispensationalist Left Behind books. (The last book in the series, Glorious Appearing , however, broke with tradition on this point. The writers actually possessed the chutzpah, if that is the right word, to attempt to depict, in straightforward narration, the absolute end of history and the triumphant return of the Judge and King whose judgments brook no appeal and whose kingdom will have no end. That is more than St. John dared to do.)

Books in this category, while they vary greatly in literary and theological quality, do take the notion of unveiling, disclosure, seriously. We see in them what is distinctive about the Christian apocalyptic vision in the strong sense of the term, the sense associated with St. John’s Revelation: that the ultimate Unveiling is so comprehensively shattering that the very history whose meanings are suddenly visible must instantly end.

The history of this world, so the Apostle seems to teach us, cannot bear the weight of its full meaning. The arrival of that meaning in its completeness marks the end of the history itself. But such completeness is not instantaneous: The unveiling occurs either with a slow waxing of revelatory power or else gradually, in stages, according to one’s eschatology.

In Michael O’Brien’s Father Elijah (the first of a series), the priest of the title tells a friend: “The apocalypse is not melodrama. If it were, most people would wake up and see the danger they are in. That is our real peril. Our own times, no matter how troubled they may be, are our idea of what is real. It is almost impossible to step outside of it in order to see it for what it is.” This claim illustrates O’Brien’s belief that, as he puts it in the introduction to the novel, “the ‘end times’ begin with the Incarnation of Christ into the world, and there remains only a last battle through which the Church must pass.” Thus the first letter of John: “Little children, it is the last hour.”

For O’Brien, while John’s Revelation contains elements of prophetic prediction, it is primarily a guide to what now is, to the circumstances in which Christians at this very moment struggle. What is revealed is, above all, the meaning of the spiritual environment we now inhabit. For those closely attentive to the book of Revelation—and, O’Brien suggests, to John Henry Newman’s four sermons on the Antichrist, written when he was still an Anglican—there is an imperceptible clarifying of vision, a disclosure that enlightens the spirit as the dawn enlightens the physical landscape.

To Make Us See

I imagine that this passage from Newman’s second sermon on the Antichrist was strongly in O’Brien’s mind (and in that of his protagonist):

What we want, is to understand that we are in the place in which the early Christians were, with the same covenant, ministry, sacraments, and duties;—to realize a state of things long past away;—to feel that we are in a sinful world, a world lying in wickedness;—to discern our position in it, that we are witnesses in it, that reproach and suffering are our portion,—so that we must not “think it strange” if they come upon us, but a kind of gracious exception if they do not;—to have our hearts awake, as if we had seen CHRIST and His Apostles, and seen their miracles,—awake to the hope and waiting for His second coming, looking out for it, nay, desiring to see the tokens of it, thinking often and much of the judgment to come, dwelling on and adequately entering into the thought, that we individually shall be judged.

These he described as “acts of true and saving faith.” The “one substantial use of the Book of Revelations [sic], and other prophetical parts of Scripture,” is

to take the veil from our eyes, to lift up the covering which lies over the face of the world, and make us see, day by day, as we go in and out, as we get up and lie down, as we labour, and walk, and rest, and recreate ourselves, the Throne of GOD set up in the midst of us, His majesty and His judgments, His SON’S continual intercession for the elect, their trials, and their victory.

Newman is an interesting figure to invoke in this context. He writes at the outset of these four sermons that, in interpreting Revelation, “I shall follow the exclusive guidance of the ancient Fathers of the Church” and yet he admits soon after that “in this matter [that is, prophecy] there seems to have been no Catholic, no universal, no openly declared traditions; and when they [the Fathers] interpret, they are for the most part giving, and profess to be giving, either their own private opinions, or uncertain traditions.”

There were, in fact, at least two major traditions among the Fathers regarding the interpretation of Revelation: one historical, primarily futurist, seeing the book as presenting predictions of coming events; and the other being (by contrast) allegorical and ahistorical, understanding the book to offer always relevant disclosures of the condition of the Church amidst its enemies. (The second was promoted primarily by the Donatist theologian Tyconius and then affirmed and elaborated by, of all people, Augustine.)

Newman strikes the Augustinian note, with its emphasis on how “we are in the place in which the early Christians were.” But elsewhere in his four sermons he considers which of Revelation’s prophecies have been fulfilled and which remain to be fulfilled. Newman is divided between the futurist and the allegorical teachings of the Fathers.

And so is O’Brien. It is in the historically minded spirit that the pope asks Elijah, “Do you understand that in those days every human being will be put to the test? Each will be asked to render an account of himself? Do you realize how universal this trial will be? How dreadful will be the cost of faithfulness?” But in the novel few are so aware; few have the veil lifted from their eyes; few sense that history may be moving towards its culmination.

Persecution of the Church increases without anyone paying particular attention, in part because the suffering is subtle, cast in the forms of education, therapy, and training; and also in part because so many friends of the Antichrist (witting or unwitting) shape the policies and acts of the Church. The pope is beleaguered even within the Vatican, while the nameless president of an emerging world government carefully builds trust and accrues power. The world will end with a bang rather than a whimper, but most will be quite shocked when the bang happens.

LaHaye’s World

But things are very different in the theological and fictional world of LaHaye and Jenkins. By the fourth book in the series, Soul Harvest—which covers a period rather early in the seven years of the Tribulation—the writers are at pains to insist that there can be no uncertainty about the identity of Nicolae Carpathia or his hostility to God and God’s people. Their theological mouthpiece, the evangelist Tsion Ben-Judah, writes, “If there are still unbelievers after the third Trumpet Judgment, the fourth should convince everyone. Anyone who resists the warnings of God at that time will likely already have decided to serve the enemy.”

If O’Brien’s Elijah believes that “it is almost impossible to step outside of [our idea of the world] in order to see it for what it is,” LaHaye and Jenkins contend that at a certain point in the career of the Antichrist it will become impossible not to see the way things really are. The line between Christ and Antichrist will be unmistakably drawn; people will need to do no more than decide which side of the line they’re on.

And once they decide, it often becomes impossible to rescind that decision, as we see in the series’ penultimate novel, Armageddon:

“I’ve changed my mind, want to take it all back . . .”

“But you can’t.”

“I can’t! I can’t! I waited too long!”

Rayford knew the prophecy, that people would reject God enough times that God would harden their hearts and they wouldn’t be able to choose him even if they wanted to.

Incidentally, I have no idea what “prophecy” LaHaye and Jenkins are referring to. We are told in Revelation 9 that those who survive the plagues released by the seven trumpets do not repent of their sins, but that offers no warrant for this scene. In any case, this scene reveals that in the world of Left Behind, contra O’Brien, the Apocalypse is melodrama. People do indeed “wake up and see the danger they are in”—but many of them respond to that danger by blaming the Christians for all their misery and siding with the Antichrist.

To borrow Dante’s terms, in the Left Behind books the Evil One abandons froda for forza—fraud (deceit) gives way to the raw display of force. In the tenth book, The Remnant, the point is reinforced when the hero thinks, “For most people, doubt was long gone by now . . . there were few skeptics anymore. If someone were not a Christ follower by now, probably he had chosen to oppose God.”

It might appear that this picture of the End Times contradicts at least one of St. Paul’s statements, since in his second letter to the Thessalonians he writes of “those who are perishing” that “God sends them a strong delusion, so that they may believe what is false.” But in the reading of LaHaye and Jenkins, I infer, the “strong delusion” concerns the outcome of events, not their character.

That is, people will not be deluded into thinking that they are servants and lovers of Christ when they are in fact his enemies, but they will be deluded into believing that Christ can and will be vanquished. Thus, unbelievers in the last days mistake the balance of power in the universe, but do not justify their actions by self-deceiving claims that their cause is Christian or godly or virtuous.

Not a Thriller

The Left Behind books eliminate the element of self-deception as described by Paul and bring the two sides of the fundamental conflict into straightforward and open opposition. When LaHaye and Jenkins do this, and thereby turn their account of the End Times into an utterly conventional thriller, with all the apparatus familiar to readers and viewers of that genre, they are making literary decisions consistent with their theology. If the Last Days are intrinsically melodramatic, then a melodramatic literary genre—with its high suspense, intrigue, games of hide-and-seek, and perfectly differentiated Good Guys and Bad Guys—provides the right way to represent it, at least until the Glorious Appearing, when, presumably, the rules will change.

By contrast, the thriller elements in Father Elijah—disguises, fake identities, spies, electronic surveillance—seem, to me at least, rather at odds with O’Brien’s theology. Because of his distinctive talents and experiences, and the role he agrees to play for the pope, Elijah is almost the only person in the world experiencing the onrushing end of history as a thriller. I found it hard, when reading the book, not to keep recalling that in this book the vast majority of the world’s faithful Christians haven’t the first idea how close they are to the Lord’s return.

There is a sense in which O’Brien ought to be writing about them rather than about a figure out of melodrama like Father Elijah. He has said, echoing the sermon from Newman I quoted earlier, that “wanting neat fortune-telling packages about the near future is really in a sense undermining the spirit of vigilance. A great mistake is made by writers when they predict events, or interpret too subjectively the details and personalities of their times.” Yet these are just the matters about which his hero is, and must be, obsessively concerned.

Being so concerned with them does not come naturally to Father Elijah, though, the way it does to the Tribulation Force in the Left Behind books, and when both the scene and the tone of the novel shift and Father Elijah finds himself in a place of contemplation and prayer, where the meaning of events is disclosed to him through mystical visions rather than through clandestine meetings in shabby restaurants and secret documents hidden in ravaged houses, one senses that the priest and his creator are both more comfortable, more at home. The eternally relevant aspects of John’s Revelation evidently appeal to them more than the predictive ones.

I have given here but a cursory glimpse at these two fictional worlds; but it is enough, I hope, to show that theological positions have literary consequences, that the way O’Brien on the one hand and LaHaye and Jenkins on the other understood eschatology had specific consequences for their narratives, and that Protestant dispensationalist thought produces a different story than does Catholic eschatology.

Elijah’s Tension

But I want to return to Father Elijah for a few moments, to consider that book in more detail, because, as I have already suggested, its fictional method stands in a kind of tension with its eschatology. There is no such tension with the Left Behind books: Their narrative world is consistent with their authors’ (melodramatic) eschatology, and if you find the latter appealing, you will probably not have much quarrel with the former.

About them I will have little more to say, except this: LaHaye and Jenkins favor a step-by-step interpretation of the End Times derived from their belief that the visions given to Daniel and to St. John appear in strict chronological order, with each vision corresponding to a particular historical event. What this means for their fiction is that, from the very first book, the immediate coming of the Antichrist and the subsequent Tribulation are assured.

In this variety of dispensationalism, once the Rapture occurs, the Cosmic Clock starts ticking, and it will continue to tick (punctuated by a series of events that are utterly unsurprising to all readers of Scripture) until, seven years later, Christ returns in glory. Therefore, throughout the books we get many sentences like this: “They still had nearly five years until the glorious appearing of Christ to set up his thousand-year reign on earth”; “Buck longed for the end of all this and the glorious appearing of Christ. But that was still another three and a half years off”; and “From the commotion down front and from his view of the platform via jumbo screens nearby, it was clear to Mac that Nicolae [Carpathia, the Antichrist] had suffered the massive head wound believers knew was coming.”

But in Father Elijah we can never be so sure of anything. All the signs point towards the president of the Federation of European States being the Antichrist, and in one confrontation with Elijah, the president seems to confirm all those suspicions. Yet, even after that dramatic confrontation, O’Brien writes:

Within the box of time a drama had been enacted. The final scenes were approaching, but it might be that other births and deaths awaited this aging planet. Night and day. Seed time and harvest. Thrones rising and falling. The Word and the Antiword circling each other endlessly in a combat from which there was neither escape, nor relief nor truce. As long as man remained man, there would arise again and again the machinations of those who had no hope beyond the tactics of worldly power; always they would kill the gentle in their desperate efforts to rearrange the furniture on the stage. . . .

To the Desert

As Elijah meditates on these truths, his thoughts give way to a series of visions:

He saw many scripts and many audiences. Palaces fell and the dwellings of the humble rose again from the ruins. He saw a world covered with the activities of the holy angels, and the songs of man feebly greeting them, as the morning star greets the dawn. But he also saw dragons coiling about cities and devouring wave upon wave of human souls who dwelt in them, as if the city of man were the city of eternal strength. Cities built by men who would not be born for another ten thousand years.

The ache and the futility of it hit him hard.

You see that time must have an end, said the voice.

Elijah begins to plead for God to hold back his hand of judgment, just as Abraham pled for God’s forbearance towards Sodom and Gomorrah. But though the voice argues with Elijah for a while, in the end it falls silent. And the book concludes without any definitive answer being given to the question of whether this is the end of time, or just another episode in the circling combat of Word and Antiword. Even the name of the hero, intended to remind us of God’s promise at the end of Malachi that Elijah will return before “the great and terrible day of the Lord,” is not definitive—perhaps he is not that Elijah.

This move might seem rather surprising. But that shift of place and tone I mentioned earlier, which happens about four-fifths of the way through the book, is a great clue. The setting of the novel moves from cosmopolitan Italy to the countryside of Asia Minor around what was once the city of Ephesus. The apparatus of the thriller is suddenly and completely discarded in favor of a picture of desert spirituality; surveillance equipment gives way to fasts, meditations, visions; James Bond yields to St. John of the Cross.

De gustibus non disputandum est, of course, but to my taste this dramatic shift is an aesthetic failure—I sense the building of an escape hatch for an author who has set up a conflict he doesn’t know how to resolve. It makes me wonder if it was not a mistake for O’Brien to take up the elements of the thriller in the first place.

Yet the book’s change of gears is illuminating in that it brings the book’s literary form more into conformity with its author’s theology. For if the End Times did indeed begin with the birth of the Messiah, and all that remains is the Last Battle, then there is little point in reading the signs of the times with the kind of scrutiny counseled by dispensationalist theology. In O’Brien’s world, to engage in comparative studies of Daniel, Mark 13, First and Second Thessalonians, and John’s Revelation with the morning’s New York Times is a fruitless activity; one would better serve oneself and God by withdrawing into contemplation, seeking those texts’ ever-relevant disclosure of the spiritual structures that have given shape to the world since Bethlehem’s manger and will continue to do so until the last sands trickle through history’s glass.

The Dimming Earth

Moreover, it could be argued that not only the thriller but even the novel itself is fundamentally inappropriate as a vehicle for conveying this eschatological vision—that, as I said at the beginning, the Apocalypse cannot be narrated. The novel is above all a realistic medium, devoted to representing as faithfully and even minutely as possible the textures and themes of everyday life; yet what Newman counsels, and O’Brien’s Elijah exemplifies, is a loss of interest in those very everyday textures and themes, a dimming of the physical eye so that the inner eye can grow sharper, more discerning of spiritual truth. As the hymn has it,

Turn your eyes upon Jesus.

Look full on his wonderful face

And the things of earth will grow strangely dim

In the light of his glory and grace.

The lifeblood of realistic narrative is “the things of earth,” that physical surround that for Newman is but “the covering which lies over the face of the world.” Perhaps now, in what we might call “normal history,” that covering reliably reveals at least the basic outlines of the way the world truly is; perhaps now, then, we have reason to attend to the details of the created order. But the onset of the Apocalypse suggests, if indeed it does not promise, the collapse of the normal, an ever-growing sense that the covering now obscures the face of the world and must be torn away.

Christian theology has always depended on the distinction between general and special revelation—God’s two books, Nature and Scripture—but the last pages of Scripture suggest that the book of Nature will one day be closed, and closed forever. (Thus Revelation 6:14, when the sky rolls up like a scroll.) If the first pages of Scripture describe for us the making of the greater light to rule the day and the lesser light to rule the night, its last pages tell us that “they will need no light of lamp or sun, for the Lord God will be their light.”

The transformation of genre that occurs near the end of Father Elijah suggests that this closing of Nature’s book will be accomplished gradually—that “the things of earth will grow strangely dim” in preparation for the Second Advent of the one who will enlighten the eternal City. Or, to use Newman’s metaphor, the prayerful and discerning Christians will come to realize that the “covering” we call Nature now hides more than it reveals, and must be lifted—and that prayer, fasting, and meditation are the powers that lift it.

In The Last Battle, the conclusion to the Narnia series, C. S. Lewis has Aslan bring the chronicle of Narnia itself to a close. “All the stars were falling,” he writes. “Aslan had called them home.” Soon thereafter, Aslan commands the Time-giant to “make an end”; the Giant extends his arm and crushes all light from the sun; Peter, the High King, closes and locks the great Door; and Narnia is no more.

The children and their friends live now and always in Aslan’s country, and for a few pages—pages that are not, I believe, among the more successful in the stories—Lewis sketches for us what Aslan’s country is like. But it can be only a sketch. Aslan utters his famous final words: “The term is over: the holidays have begun. The dream is ended: this is the morning.” And then the final paragraph:

And as he spoke he no longer looked to them like a lion; but the things that began to happen after that were so great and beautiful that I cannot write them. And for us this is the end of all the stories, and we can most truly say that they all lived happily ever after. But for them it was only the beginning of the real story. All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnia had only been the cover and the title page: now at last they were beginning Chapter 1 of the Great Story, which no one on earth has ever read: which goes on for ever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.

Say No More

I have spoken of one book closing, yielding forever to another; Lewis writes rather that what we thought was a book, or a even series of books, is but the beginning of another, and an infinite, tale. Lewis is paying a massive debt here, but not primarily to John the Revelator (as the old song calls him) but to Dante the poet. For there are different ways for the world to end—just as, Eliot teaches us in “Little Gidding,” there are several places that are the world’s end.

For the earthly friends of Aslan who die in a train accident, this world ends and the door into Narnia is forever closed; for Dante, the unveiling of the cosmic hierarchies concludes with a vision of Divine Love which, in a different way, brings his world to an end. He is able to stammer out, fitfully, some fragments of vision, and among his last is that of a book—a codex, not a scroll, and therefore with many freely open pages that are yet bound together:

I saw how it [that is, Eternal Light] contains within its depths

All things bound in a single book by love

Of which creation is the scattered leaves;

But while he can tell us that his “heart leaped up in joy” at what was revealed to him, he soon can say no more of it—the “inexpressibility topos,” as the great medievalist E. R. Curtius called it, the ritual confession of the powerlessness of words. And then, when he thinks that all has been revealed to him, there is a last burst of enlightenment at which the poet, now utterly overwhelmed, falls silent.

We hear nothing of his return to the world of the living, no reflections on his marvelous journey; instead, we leave him at the world’s end, where words are not merely inadequate but rather impossible. If, as we draw closer and closer to the consummation of history or the limits of created being, our standard forms of narrative expression grow increasingly suspect, once those doors have been closed and locked, expression simply and utterly ceases.

In the end (a common phrase, but heavier than usual in this context) Dante may be our best guide to these vexing matters: He knows when to shut up. Generally speaking, we are not aware of anything that is intrinsically, necessarily, beyond our ability to speak of it. Only someone like Wittgenstein, whose mystical temperament was not wholly unlike Dante’s, could think to say, “That of which we cannot speak, we must pass over in silence”—and even Wittgenstein has typically been understood to be making, there, a comment on philosophical method, rather than confessing awe in the face of a world that dwarfs the resources of language.

In fact, I believe, Wittgenstein was speaking both of philosophy’s limits and the limits of expressive representation; and if we take Wittgenstein as we should, we will not only be shamed before the richness of the daily world, we will recognize the futility, even the frivolity, of trying to tell anyone anything about the world’s end. Perhaps, then, Roz Chast has shown us the best we can do: It’s a-comin’, and it’s gonna be big. •

“The Inexpressible Apocalypse” is a revised version of Jacobs’s address to Touchstone’s 2003 conference, “The Time Is Near: The Apocalyptic Imagination in an Age of Anxiety.”

A Plague of Denial

In the Left Behind books, the followers of the Antichrist seem to know who he is, but think he is going to win. I must say that this notion seems strange to me. I cannot, I find, imagine a Satan who does not employ deceit, or people who are not pleased to be deceived in order to place themselves on the side of the angels (as they think it).

I find myself meditating on the Old Testament prefiguring of the great Judgments to come: the plagues visited upon Egypt in the time of Moses. Again and again, when it seems impossible for Pharaoh to miss the message, he misses it. Denial may not be just a river in Egypt, as the saying goes, but in the book of Exodus it seems to be an Egyptian malady.

This kind of denial is often found in literary treatments of imminent catastrophe. In the Lord of the Rings, for instance, when Theoden King of Rohan refuses to accept that open war is upon him and his people, or in the Harry Potter books when Cornelius Fudge, the Minister of Magic, steadfastly denies that Lord Voldemort has returned until it is simply impossible to evade the truth any longer.

I would like to claim that no work of recent narrative art exposes this kind of denial more powerfully than that shocking, offensive, and (to me) deeply moving film Magnolia. The movie is best known for its introduction, two hours into a mostly sordid story of various forms of abusiveness, of a plague of frogs.

The frogs raining from the skies and splattering onto car windshields and asphalt, and crashing through skylights, and thumping cacophonously onto roofs and gas station canopies, are portrayed as a way for God—or Someone, Something Up There—to arrest the attention of people who are ruining their own lives and the lives of those around them. Hours before the frogs fall from the sky, it’s just rain that’s falling—though in torrents—and people sit in their living rooms or lie in their bedrooms or half-recline in their cars and softly sing: “It’s not going to stop / ’Till you wise up.”

But they don’t wise up, most of them. Even when it’s just rain pouring down, it does so hour after hour, in a way quite remarkable for southern California. And long before the rain began, a young African-American boy had rapped to Jim—the cop who, for all practical purposes, is the hero of this story—“When the sunshine don’t work, the Good Lord bring the rain in.”

Yet no one seems to notice the conditions; they always have their backs to the windows; turned inward, eyes downcast or vacant, they continue to eat away at their own guts, oblivious to the external world, muttering the lyrics to a song whose force they do not seem to feel. Only the crashing of frogs onto windshields and roofs and through windows and skylights—and in one case, right onto a man’s upturned face—is sufficient to shake at least some of them from their self-referential stupors.

I cannot conceive that this pattern of deceit and self-deceit, this way we have of wearing deep grooves of untruth into our bodies, souls, and spirits, will end until the world does.

Alan Jacobs is Professor of English at Wheaton College in Illinois. His books include A Theology of Reading (Westview Press), A Visit to Vanity Fair and Other Moral Essays (Brazos Press), and Shaming the Devil: Essays in Truthtelling (Eerdmans).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor