Interview

Violence & the Lamb Slain

An Interview with Rene Girard

by Brian McDonald

Rene Girard is both one of the twentieth century’s most prominent theorists of culture and a devout Roman Catholic. Born and raised in France, Girard received his Ph.D. in history from Indiana University and has lived and taught for most of his life in America.

He combines a “deconstructionist” and “debunking” analysis of the origins and bases of human culture with an essentially traditionalist affirmation of Christianity. His cultural analysis has been praised by secular critics, even as his insistence that this very analysis should lead to Christian affirmation has shocked them. Christians are pleased that a giant of modernist and postmodernist thought is a solid Christian, but some are disturbed that he seems to “debunk” the propitiatory view of Christ’s death on the Cross. A brief outline of his thought and its development may therefore be useful before presenting the interview.

Girard’s Thought

Picture two young children playing happily on their porch, a pile of toys beside them. The older child pulls a G.I. Joe from the pile and immediately, his younger brother cries out, “No, my toy!”, pushes him out of the way, and grabs it. The older child, who was not very interested in the toy when he picked it up, now conceives a passionate need for it and attempts to wrest it back. Soon a full fight ensues, with the toy forgotten and the two boys busy pummeling each other.

As the fight intensifies, the overweight child next door wanders into their yard and comes up to them, looking for someone to play with. At that point, one of the two rivals looks up and says, “Oh, there’s old fat butt!” “Yeah,” says his brother. “Big fat butt!” The two, having forgotten the toy, now forget their fight and run the child back home. Harmony has been restored between the two brothers, though the neighbor is now indoors crying.

It would not be much of an exaggeration to say that Girard builds his whole theory of human nature and human culture through a close analysis of the dynamics operating in this story. Most human desires are not “original” or spontaneous, he argues, but are created by imitating another whom he calls the “model.” When the model claims an object, that tells another that it is desirable—and that he must have it instead of him. Girard calls this “mimetic” (or imitative) desire. In the subsequent rivalry, the two parties will come to forget the object and will come to desire the conflict for itself. Harmony will only be restored if the conflicting parties can vent their anger on a common enemy or “scapegoat.”

With the lucidity characteristic of French thought before the “deconstructionist” writers, and a consistency reminiscent of Calvin, Girard shows, throughout the body of his work, how his theory of “mimetic” desire can illuminate and unify an extraordinarily disparate set of human phenomena. It can explain everything from sacrifice to conflict, from mythology to Christianity.

Mimetic desire accounts for the nature of human culture. Early human cultures, thinks Girard, must have been marked by violence as mimetic desire drew human beings into unceasing conflict. Ultimately, the object would disappear from view and be replaced by the conflict itself. Thus, most conflicts, either ancient or modern, are almost literally over “nothing,” with essentially identical rivals seeking only the prestige that comes from achieving victory over each other. (St. Augustine noted this in his Confessions, when he analyzed sports and games and marveled that the only object won in these contests was prestige gained through victory over a rival.)

Primitive societies would have few mechanisms for containing the spreading contagion of mimetic violence, so Girard concludes that such societies would have inevitably decimated themselves had they not found a mechanism for containing the conflict.

This mechanism he locates in another fundamental human characteristic: our propensity for “scapegoating.” At some stage in a cycle of mimetic violence, the community spontaneously turns on one of its members as the one who is to blame for it all. (Remember that point in innumerable movie Westerns where, in the midst of some scene of agitation and confusion, a finger gets pointed at someone and immediately a thicket of fingers is pointing at him and a lynch mob is instantly created?)

While mimetic violence divides each against each, scapegoating violence unites all against one. Thus the destruction of the scapegoat produces a genuinely unifying experience, the peace and relief of which makes such a profound impact that, over time, the hated scapegoat is turned into a god, and the community tries to perpetuate the peace-bringing effect of this original lynching by commemorating it ritually and sacrificially. Ultimately this ritualized violence becomes the basis for religion, mythology, kingship, and the establishment of those differences in role and status that are so essential to bring about internal peace. (Differentiation cuts down on mimetic rivalry since only “equals” can compete for the same object.)

Desire & Repentance

Girard’s key idea (if not the term) made its first appearance in Deceit, Desire, and the Novel (1959), the work that first brought him to prominence. In this analysis of great writers from Cervantes to Proust, Girard found that all the great novels dealt with the theme of what he then called “triangular desire” and ended with a kind of repentance: a protagonist awakening into a recognition of the wrong-headedness of a life built on the illusion of imitated desire and rivalry with others.

In Violence and the Sacred (1972), he moved from the realm of literature to that of culture itself, and added to his concept of mimetic desire that of scapegoating. This analysis of the way religion, mythology, and culture are built upon an unrecognized foundation of mimetically caused violence and scapegoating brought him considerable acclaim when it was published.

However, Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1979), though a best-seller in France, lost him much of that acclaim, for in this latter work Girard dared to assert that the shackles of sacrificial religion were broken for a large portion of mankind by the force of the biblical story in which a number of narratives reversed the classical mythological pattern by exonerating the scapegoat and showing the community to be guilty of gratuitous murder.

What most offended his secular audience was that he saw in the culmination of the biblical witness, the passion of Christ, a permanent exposé of the “the things hidden from the foundation of the world”—that both the order and disorder of human life are founded on the clashes of mimetic desire relieved by the lie of the scapegoat mechanism.

Hence, Girard identifies the foundational principle of culture as “Satan,” since it mirrors perfectly Christ’s description of “the Prince of this world,” who was moved by envy and was “a liar and a murderer from the first.” By laying down his life to expose and overthrow this kingdom built on violence and untruth, Christ also introduced the world to another kingdom, one “not of this world,” whose fundamental principles are repentance for sins instead of the catharsis of scapegoating and love of God and neighbor rather than the warfare of mimetic desire.

The death of Christ and its effects move Girard’s theory from “naturalism” to Christian affirmation, since he is convinced that the mindset of natural humanity is so wholly immersed in the “intervidual” psychology of sacrificial religion that only a divine revelation could break us free of it—or even make us recognize the suppressed lie at the basis of our existence. Hence, the very appearance of the Christ, and his successful exposure of the lies at the base of human life and culture, is a proof of his divinity, since “no human is able to reveal the scapegoat mechanism.”

Girard’s belief about the death of Christ may be no less controversial among Christians than his allegiance to Christ is scandalous to the secular world. Against the view of Christ’s death that would see him as a propitiatory sacrifice offered to the Father, Girard would argue that Christ’s death was intended to overthrow in its entirety the religion of propitiatory sacrifice, since he sees that religion as of the very essence of fallen man.

The Interview

The following interview was conducted by telephone and has been edited for clarity.

Brian McDonald: You were led to Christianity through a process that many people would find unusual: that of studying the structure of some of our great Western novels. Could you explain how the “shape” of novelistic works became a factor in your embracing of Christianity?

Rene Girard (RG): Yes. A great novel involves an experience that is spiritual; the novelist engages in reflection and comes to sense that his whole life has been based upon illusion. The character in a novel then experiences a conversion that involves a recognition that he is like those he despises. But this experience of the character is in reality a reflection of what has happened to the novelist. It is what makes him able to write the novel.

In language you use elsewhere, the novelist ceases to “scapegoat” his characters and identifies with them.

RG: Yes, yes. Now this experience of conversion is not necessarily the Christian experience of conversion, but it has that pattern. It has the Christian form in Crime and Punishment, but the same form, though not overtly Christian, takes place in Marcel Proust’s The Past Recaptured.

And you yourself?

RG: I would say that it is my own life I am describing when I discuss these matters.

I believe you have stated somewhere that this novelistic pattern originated in Augustine’s Confessions.

RG: Yes, this I think is true. Though the Confessions is different in that the conversion happened before the book was written. You see, I always think of it as something happening at the end. In my view the novelist writes the novel twice. The first time, he finishes it, but unlike God after creating the world, he looks at his work and says, “It is bad!” What is missing is something that must happen to the novelist himself. And when it happens, the novel is really viewed from a different perspective. But the pattern of conversion changing the way everything former is seen is established in the Confessions.

Reading Christ’s Death

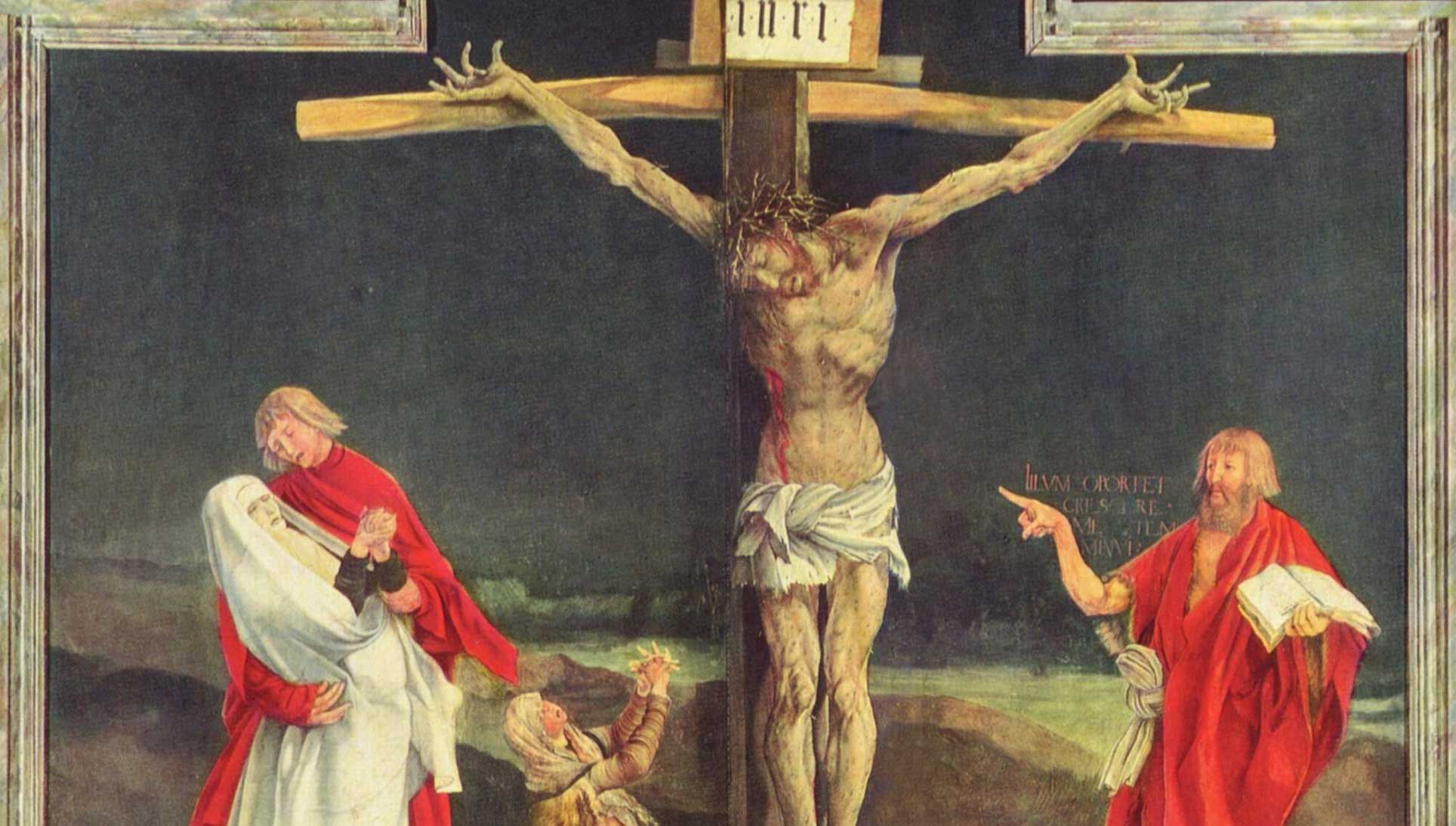

You have advocated what is seen as a “non-sacrificial” reading of the death of Christ that is significantly at odds with the usual understanding of that death as a “hilasterion” that satisfies the wrath and justice of God. Could you describe that view and how your study of the formation and maintenance of human cultures has led you to it?

RG: Oh, this is a question that will require a long answer! It is not quite true that I take what you have called a “non-sacrificial reading of the death of Christ.” We must establish first of all that there are two kinds of sacrifice.

Both forms are shown together (and I am not sure anywhere else) in the story of Solomon’s judgment in the third chapter of 1 Kings. Two prostitutes bring a baby. They are doubles engaging in a rivalry over what is apparently a surviving child. When Solomon offers to split the child, the one woman says “yes,” because she wishes to triumph over her rival. The other woman then says, “No, she may have the child,” because she seeks only its life. On the basis of this love, the king declares that “she is the mother.”

Note that it does not matter who is the biological mother. The one who was willing to sacrifice herself for the child’s life is in fact the mother. The first woman is willing to sacrifice a child to the needs of rivalry. Sacrifice is the solution to mimetic rivalry and the foundation of it. The second woman is willing to sacrifice everything she wants for the sake of the child’s life. This is sacrifice in the sense of the gospel. It is in this sense that Christ is a sacrifice since he gave himself “for the life of the world.”

What I have called “bad sacrifice” is the kind of sacrificial religion that prevailed before Christ. It originates because mimetic rivalry threatens the very survival of a community. But through a spontaneous process that also involves mimesis, the community unites against a victim in an act of spontaneous killing. This act unites rivals and restores peace and leaves a powerful impression that results in the establishment of sacrificial religion.

But in this kind of religion, the community is regarded as innocent and the victim is guilty. Even after the victim has been “deified,” he is still a criminal in the eyes of the community (note the criminal nature of the gods in pagan mythology).

But something happens that begins in the Old Testament. There are many stories that reverse this scapegoat process. In the story of Cain and Abel, the story of Joseph, the book of Job, and many of the psalms, the persecuting community is pictured as guilty and the victim is innocent. But Christ, the son of God, is the ultimate “scapegoat”—precisely because he is the son of God, and since he is innocent, he exposes all the myths of scapegoating and shows that the victims were innocent and the communities guilty.

You use the word “Satan” to describe the structural principle of human existence in which both disorder and order are built upon untruth and violence: disorder created by mimetic conflict and order restored and established by persecution and destruction of scapegoats. In the purely“anthropological” portions of your work, you seem to view this structure as a kind of necessity for early human beings. In the more “theological” portions of your work, you seem to treat it very much as what has traditionally been called Original Sin. Do you view the satanic structure as a kind of historical necessity—given the conditions of early human existence—or do you view it as a “fall” that could have been avoided? (Or is this a false either/or?)

RG: Well, I must stay within the scientific use. This is the language people speak and understand in this time. I am an anthropologist. As I view the process of hominization, it is a kind of historical inevitability. We don’t know of any other creature that practices sacrifice, and there seem to be neurological features that required this, based upon the fact that we are the most mimetic of all animals.

On the other hand, even if this had a kind of historical necessity, it is also a form of a lie. The scapegoat mechanism is something men “do but know not what they do.” It is indeed from that Original Sin and something from which redemption is required.

As a cultural theorist sticking within the limits of your discipline, you must bracket the question of Satan as a “personal” being. I am interested, however, in whether as a Christian you see Satan as a kind of “being” as well as a structure?

RG: (Laughs.) Well, I don’t know. Does it really matter? Whether Satan is a personal being or not, he is still the “prince of this world.” Existence is satanically structured whether or not he is a personal being. He is a liar and a murderer from the first, and the religion of murder and lie has founded our existence from the first. Perhaps we shouldn’t become too preoccupied with him, should we?

Besieged Christians

Most Christians have a siege mentality when confronted with modern and postmodern thought, finding the “unmaskings” of Freud, Nietzsche, Marx, or Derrida purely and simply as nihilistic threats to the gospel. However, you seem to have an essentially positive (if critical) reading of the trends of contemporary thought, believing that if its practitioners fully understood their own insights, they would find them leading toward the Christian revelation instead of away from it. If this is a correct assessment of what you are saying, what in contemporary thought seems most “retrievable” to you?

RG: Well, they are nihilistic. Nietzsche actually describes the full reality of Dionysian religion as sacrificial—and endorses it! But without the endorsement his thought is precisely what I am saying!

You have described yourself as a deconstructionist.

RG: Yes, but then one must have something to deconstruct to. Deconstructing when you are looking for the foundation underneath is a good thing.

In a striking phrase, you say that “Everything which happened to Jesus is now happening to the gospel texts.” Could you explain what you mean by this?

RG: The texts are scapegoated. They are blamed for what is wrong. And yet it is precisely these texts that have brought the scapegoating mechanism to light!

You assert that the Gospels appear to be myth but in reality are “poles apart” from myth. Why do they appear to be myth and why are they in reality “poles apart”?

RG: They appear to be myth because the death of Christ is presented as a sacrifice, and sacrifice of the scapegoat is the origin and theme of all mythology. But it is a sacrifice that refutes the whole principle of violence and sacrifice. God is revealed as the “arch-scapegoat,” the completely innocent one who dies in order to give life. And his way of giving life is to overthrow the religion of scapegoating and sacrifice—which is the essence of myth.

The heart of Christ’s sacrifice is shown in his prayer, “Not my will, but thine be done.” It was inevitable that if someone lived this life, he would suffer the death of a scapegoat, so the sacrifice was inevitable from the moment he began his ministry. But the end of that death would not be to make men feel confirmed in their lives, but to call men into question. Unlike the myths, we have a choice. Christ’s kingdom or the kingdom of Satan. When one does not accept Christ’s offer, he is of course a member of that kingdom.

Your thought at one end is extremely naturalistic and “unspiritual” (for instance, there is no inborn sense of the transcendent: the sacred is quite literally a “by-product” of our misunderstanding of the scapegoat mechanism). According to your theory, human culture seems to be explained without “remainder” as a product of wholly naturalistic combinations of biological and social forces. I do not fully understand the leap that allows you to affirm God, Christ, eternal life, and so forth, not as a revelation that simply “trumps” your naturalism (as Barth might do), but as a kind of end result of that process of thought when carried out to its logical conclusion.

RG: Well, we must speak the language of the times—which is naturalistic. My thought is no more reductionist than Paul’s when he says: “I determined to know nothing among you but Christ and him crucified.” Paul did not mean to say that there was nothing besides the death of Christ, but that all knowledge took place in understanding the crucifixion of Christ. It is from that death and the place of that death that all understanding comes. I believe that it is in that sense that my hypothesis, though I keep repeating it over and over again, is not reductionist.

Brian McDonald teaches literature at Indiana University in Indianapolis. A former Presbyterian minister who converted to Orthodoxy, he is married, with five children and attends Sts. Constantine and Elena Parish.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor