Feature

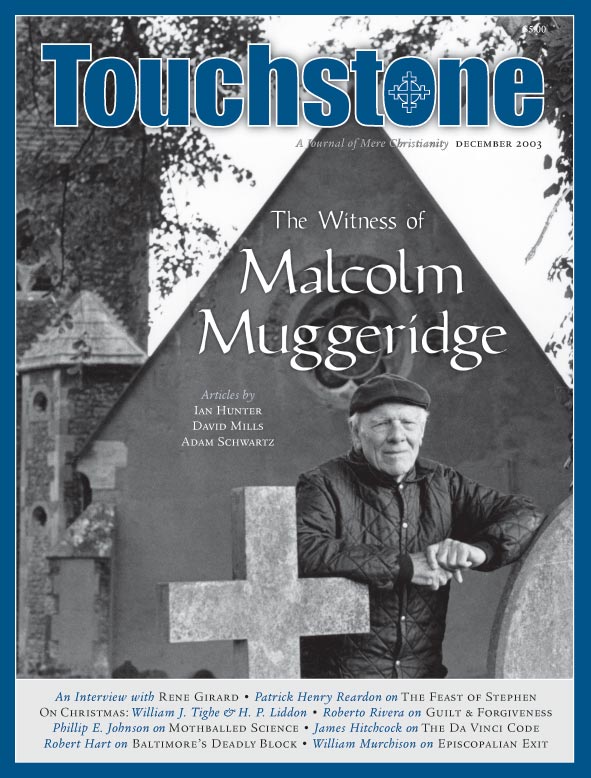

Vanity Fair’s Thanatos Syndrome

Malcolm Muggeridge, Modern Capitalism & the Culture of Death

by Adam Schwartz

Like many of his forerunners among the famous converts of the last century, Malcolm Muggeridge was an acute social critic whose spiritual pilgrimage was spurred on in crucial ways by his qualms about twentieth-century culture’s direction. Among his principal anxieties was the materialistic ethic he associated with modern capitalism, one he judged corrosive of the core social institution, the family, and one especially manifested in the eugenic impulse. He therefore reproved Western consumerism consistently, and eventually decided that orthodox Christianity was the best—perhaps the only—basis for resistance.1

He sensed early in his life (he was born in 1903) a need to choose to pursue either the quality of life or the sanctity of life, and he chose the latter. He found it to be part of the way of love and the imagination, whereas the former belonged to an ethic animated by power and the will. He increasingly felt that modern Western society privileged the quality of life over its sanctity, and he condemned the culture of consumerist concupiscence that arose from this choice.2

Greed the Mainspring

Muggeridge argued consistently that greed is the mainspring of Western capitalist society and “about the most contemptible of all” such bases, generating an economically lucrative but ethically hollow culture in which the pursuit of happiness was merely the pursuit of pleasure.3 Such a hedonistic civilization was “the most horrible and degraded that ever existed on the earth” and should not be considered civilized.4 He often dubbed the affluent West a gilded “pigsty” and a “zoo.”5

Initially, Muggeridge found consumerist capitalism destructive of individual freedom and integrity. At times he invoked Hilaire Belloc’s idea of “the servile state,” arguing that twentieth-century Western man’s pursuit of pleasure in security would lead him to forsake his freedom voluntarily, creating a “freely constructed concentration camp.”6 Echoing C. S. Lewis and George Orwell, he feared in 1954 that so surrendering personal liberty would entail the “final obliteration of the individual as we know him today” and the advent of a race of mass-minded slaves in thrall to sensuality and the passions: “Leviathan’s belly [is] warm and secure, but dark and confined.”7

Muggeridge regarded the British welfare state as a manifestation, rather than a mitigation, of capitalist materialism’s deadly cultural effects. He contended that the welfare state embodied consumerism’s “shallow and fatuous” ethos, and he thought that concentrating state power to facilitate social security would exacerbate the self-enslavement already fostered by dependence on oligopolies for an everlasting stream of consumer goods and the financial wherewithal to purchase them, leaving Westerners “sleepwalking into our own Gulag, incarcerating ourselves in our own high-rise prisons.”8

Besides threatening man’s liberty and identity, Muggeridge averred, capitalism also spawned an inhuman homogenization and humorlessness, a utilitarian aesthetic inimical to genuine imaginative art, and an unjust distribution of wealth. The latter grew, in part, from the misapplication of Darwin’s model of animal biological development (the “survival of the fittest”) to human society. He concluded that when future eras surveyed the twentieth-century West, they would see a society ruled not by men like gods, but “men like apes . . . and even that will seem rather hard on the apes.”9

Muggeridge was convinced that a culture so seemingly at odds with human nature was unsustainable. Modern Western society was a “nightmare,” one afflicted with a neurosis or madness arising from its consecration of the pleasure principle and its consequent denial of life’s essentially tragic nature.10 He thus felt that wealth was bringing widespread individual and collective despair, especially in places of exemplary affluence like Scandinavia and America, concluding in 1983 that “to believe in man’s capacity to create his own circumstances is a doctrine of despair.”11

Unsurprisingly, then, he considered consumerist capitalism an incarnation of, and contributor to, the “death wish” of the modern West, which was seeking to commit civilizational suicide. As early as 1940, he detected a Western craving for “violence and bloodshed” in entertainment to relieve the “boredom and desolation of mechanized life,” making carnage the “poetry of mass production.”12 By 1958, he was asserting that “the trouble with capitalism is . . . that for the sake of a shilling today it will advance causes which will destroy it tomorrow,” such as trading with Communist states.13

Four years later he speculated that “perhaps the pursuit of happiness will end in extinction,” and by 1970 he was certain that “a neurotic passion to increase consumption” could only precipitate such a culturally self-destructive climax: “We press on through the valley of abundance that leads to the wasteland of satiety, passing through gardens of fantasy; seeking happiness ever more ardently, and finding despair ever more surely.”14

Consumer Idolatry

Muggeridge linked much of this cultural malady to secularization. “Faith and its sacred texts are of the desert, not of affluence; on sandy wastes and rocky mountain tops men think of God; in the lush, sheltered plains forget Him.”15 By 1981 he identified consumerism as ego-cenctric idolatry: “In the twentieth century, man’s created the most disastrous of all images which is himself and he falls down and worships him. . . . Never in human history have the unworthwhile things of life been presented so alluringly, through advertising. . . . [T]his is Vanity Fair into every single person’s sitting room, hours and hours of it, day after day.”16

More specifically, Muggeridge regarded this self-worship as sex-worship. Sex, he said, “is the mysticism of materialism.” A consumerist culture enshrines sex as one of its “tribal gods” and then exploits it in advertisements to nurture the system of chronic getting and spending: “In a society whose most pressing need is to create wants and desires, sexual appetite is obviously a valuable adjunct to salesmanship.” Besides making sex a stimulant to consumption, a consumerist culture also uses it as a narcotic: “Nothing is more calculated to induce acceptance of the social and economic status quo than erotic obsessions. . . . Unfolding the month’s playmate in Playboy magazine, any tendency to think and question things is automatically extinguished.”17

Muggeridge thought a culture founded on such fantasies was part of the illusory “Legend” rather than substantial “Life,” and was hence inherently friable.18 But he also saw that in the mid-twentieth century such a culture seemed to conquer all others. He wrote in the late 1950s that “for the first time in the history of the world 99.99 percent of mankind want the same things—viz.: American way of life.” He thought this civilization was symbolized by “the logos of our time,” ubiquitous neon signs advertising Food, Beauty, Drugs, and Gas: “the means to sustain life, to reproduce it, to protract it, and to achieve mobility. These are our Four Pillars.”19

Muggeridge held that orthodox Christianity offered the lone satisfactory alternative to this ethic. “If only the people had been up to supporting their Catholic Church, there would have been no capitalist system, because you couldn’t have had a capitalist system without usury.”20 He thought orthodox Christianity contravened what Max Weber called modern capitalism’s hallmark, its stress on constantly increasing production: “It is difficult to see how [this] concept of a continuously expanding economy can be fitted into the Christian canon. . . . The basic difficulty remains that Christian doctrine calls for abstinence whereas our way of life requires indulgence. . . . Between Madison Avenue and Gethsemane there would seem to be a wide and impassable gulf.”21

Specifically, Muggeridge felt that orthodox Christian rebellion against the worship of the Gross National Product on behalf of the gospel would supply remedies to many of materialism’s malignancies. To him, Christianity valued the sanctity of life more than its quality, because it taught that “in all creation the hand of God is seen . . . in the first stirrings of life in a fetus and in the last musings and mutterings of a tired mind.”22 Hence “happiness—which usually means pleasure—as an end or pursuit runs directly contrary to the Christian way of life,” for Christianity is “the dispensing rather than the consuming society.”23

He consequently judged Christian charity a more radical and more humanistic (and thus more salutary) balm for social injustice than the welfare state, because it is inspired by belief in man’s eternal destiny, and his ensuing unique individual dignity, instead of concern merely for his material well-being. “Welfare is for a purpose . . . whereas Christian love is for a person. The one is about numbers, the other about a man who was also God.” He argued that those who prioritize the soul treat bodily needs more tenderly than do materialists.24

He affirmed that transcendent relationship is more crucial to human flourishing than ameliorating temporal poverty: To say “‘Dadda’ to God is what people need even more than [the] minimum wage.”25 Muggeridge therefore located authentic freedom not in the fulfillment of material desires, but in humble obedience to and service of this Father, “when you can kneel down and say ‘Thy will be done’ and really mean it in the fullest and most absolute sense, that whatever God wills is the best thing . . . ‘whose service is perfect freedom.’”26

Christianity’s Cure

Muggeridge also argued that orthodox Christianity could ease modernity’s psychic ills. He thought its affirmations of Original Sin and asceticism could help restore sanity by revealing consumerism’s inability to quench human desires and thereby could quiet restlessly concupiscent minds and hearts: “It is the children of affluence, not deprived monks, who howl and fret in psychiatric wards.”27 He similarly saw in the Christian idea of sex as a “sacrament of love” a compelling counterweight to the treatment of sex as a commodity used to serve (and acquire) wealth and power.28

The Cross is the antidote to narcissism: When “contemplating God in the likeness of man” upon it, “with all our earthly defenses down and our earthly pretensions relinquished . . . we may understand how foolish and inept is man when he sees himself in the likeness of God.”29 Worldly despair can only be cured by otherworldly hope:

I only began to hope when I ceased to be a materialist. . . . Material hopes cannot survive because they are material—that is, subject to corruption . . . [but] men [are] not made happy or unhappy, serene or unsettled by their circumstances whether physical or social or economic, but according to their sense of sharing a destiny which transcends their earthly circumstances, and consequent brotherliness between one another.30

As Muggeridge regarded Christianity as his age’s last, best hope of cultural renewal, he cautioned the contemporary churches against their growing willingness to accommodate modern mores. From the 1930s, he noticed a tendency among twentieth-century Protestants to baptize “romantic materialism” by transforming “creeds into political programs, and transcendentalism into utopianism,”31 and he was alarmed when he saw the Catholic Church also adopting “a kind of consumer religion” in the aftermath of the Second Vatican Council.32 As he put it in the late 1960s,

The Christian Church is inevitably involved in this death of our civilization. . . . If you consider the death symptoms, the foremost is an increasing preoccupation with the material things of life. Here the Churches go with the popular trend, and endorse, and even enhance, our affluent society’s materialist standards . . . [and they therefore] will expire with our expiring civilization.33

This suicidal disavowal of traditional Christianity’s distaste for materialism became a central stumbling block in Muggeridge’s own spiritual journey, as he complained for years that “an aspiring Christian today is left in a kind of catacomb of his own making,” being unable to find any corporate citadel of unalloyed orthodoxy.34 In such circumstances, he felt, it was better to sing a solo version of “Backward Christian Soldiers” (the title of one of his most famous essays) than to join the chorus of any church and its bare ruined choirs.35

Muggeridge localized this sensed conflict between consumerism and Christianity in the fate of the traditional family and sexual morality. He deemed family life “the most agreeable form of happiness . . . available to us here on earth,” and by the 1950s he upheld the orthodox Christian position that “the family is, and ever must be, the basic and true unit of society.”36 Indeed, his disaffection with Communism stemmed partly from the early Soviet attempt to abolish the traditional family, which Muggeridge felt had left only “teeming misery” as its legacy.37

The Unfolding of the Death Wish

Yet he became increasingly anxious that the West was engaged in a similar assault. He argued that its favoring of the quality over the sanctity of life engendered sensualist attitudes inimical to the family: “The quality of life means simply gorging, fornicating, and never having children and so on.”38 Moreover, because the affluent “have no material obstacles to shedding relationships,” an acquisitive society erodes and degrades ties between spouses and between parents and children.39

He found it unsurprising that a culture that made sex a commodity considered the marriage bond a contract rather than a covenant, and regarded the family as “a factory farm whose only concern is the well-being of the livestock and the profitability of the enterprise.”40 Such sub-human conceptions of the core human institution were a further indication of the modern West’s death wish.41

In fact, Muggeridge anticipated John Paul II’s idea of “the culture of death.” His belief that the sanctity of life mattered more than its quality led him to posit that either “no lives are worth living or that all lives are worth living, but not that some lives are worth living and others not.”42 By contrast, modern Western society subscribed to the eugenic principle that only lives that are economically efficient and materially productive are worth sustaining, and he was not surprised to see it condoning abortion and euthanasia—what he (injudiciously) called the “humane holocaust”—in the name of the quality of life. “The logical sequel to the destruction of what are called ‘unwanted children’ will be the elimination of what will be called ‘unwanted lives.’”43

Similarly, he foresaw the possibility of the terminally ill and the mentally ill and retarded having their organs harvested to be transplanted into more industrious citizens, and feared that a hedonistic polity would use genetic engineering to create a homogenous population of “the model ad-man with his everlasting smile exposing his perfect teeth.”44 The West’s growing acceptance of all these practices and beliefs was of a piece with its deepening environmental degradation, possession of nuclear weapons, and perpetration of the psychological violence of propaganda: They all reflected a drive towards “death, destruction and darkness, not life, creativity and light . . . a death wish inexorably unfolding.”45

For Muggeridge, one crucial expression of the death wish was artificial contraception. He believed that sundering sex’s procreative from its unitive function fostered many of the trends he feared. “The purpose of [sex] is procreation, the justification of it is love; if you separate sex from procreation and love, very rapidly you turn it into a horror.”46 For example, he argued that only a society characterized by this bifurcation could simultaneously sanction in vitro fertilization and abortion.47 He judged this contraceptive mentality an essential element of consumerist society’s eugenic bent, as it allows “all our procreation [to be] done in test tubes” by genetic engineers eagerly creating an army of ad-men while “leaving us free to frolic with our sterilized bodies as we please, unconstrained” by “unwanted children.” He regarded contraception as “the crowning glory of the pursuit of happiness through sex,” but deemed this quest for an “unending, infertile orgasm” a “death-wish formula if there ever was one.”48

Muggeridge also charged that his epoch’s exponents of contraception were driven in part by greed. He held that the beneficiaries of Western capitalism had devised the “fantasy” of overpopulation to avoid redistributing their wealth by instead urging and enabling the poor in distant lands to reduce the size of their families: “They ask for bread and we give them contraceptives.”49 Similarly, the healthy wealthy of the West increasingly regarded euthanasia—“considered medical execution”— as cheaper and more cost-effective than paying higher taxes or insurance premiums to provide extended palliative care to the aged and the infirm.50

In his view, these beliefs and measures were human sacrifices to the idol of Mammon that portended the ultimate death wish. “If the eugenicist’s dream were ever to be realized . . . God would really be dead. The only way God could die would be if we retreated so far into our egos and our flesh, put between us and him so wide a chasm, that our separation became inexorable.”51

The Basis for Life

Muggeridge relied on both nature and grace to combat this “Thanatos syndrome.” From at least 1940, he criticized efforts to ease legal restrictions on divorce and abortion, and in 1949 he rebuked Orwell for favoring assisted suicide for the elderly.52 In his later years, he wrote an anti-euthanasia play (Sentenced to Life), became a pro-life activist and a vegetarian, and refused routine medical procedures (like cataract surgery) that he saw as an unhealthy denial of the aging process by a materialistic society dedicated to the quality of life.53 He also noted the irony that a culture so fearful of mortality’s inevitability was the same one that endorsed death as the best way to dispose of its “unwanted” members.54

But he also felt that a culture of life required a firm religious basis and assistance from the institutional churches. In 1978, for instance, he conceded that, absent belief in God, there is no compelling ground for condemning euthanasia.55 He was thus disturbed by what he deemed the Christian churches’ growing accommodation of the “permissive society” and its “New Morality” favorable to contraception, divorce, and abortion, particularly during the “sexual revolution” of the 1960s and 1970s.56

He was hence deeply moved when Pope Paul VI issued Humane Vitae in 1968, regarding this reassertion of traditional Christian sexual ethics as “the most amazing, amazing gesture to have been made in the circumstances of the twentieth century . . . it was an extraordinary step to take, against the whole trend of things.”57 Despite his qualms about the Catholic Church’s rapprochement with modernity, the moral teachings of Paul VI and John Paul II convinced Muggeridge that Rome, alone among current Christian bodies, would continue to rebel corporately against hedonistic materialism on behalf of the sanctity of life.

Although he claimed to have always found this Catholic approach to the modern moral crisis appealing, it was not until 1982 that he was persuaded fully that, whatever its other changes, the church would remain constant in its respect for life at all of its stages.58 In November of that year, he was received into the Catholic Church, saying that its uncompromising belief in the sanctity of life “made me feel that I must at the end of my days stand up and be counted with this Church which alone, alone in the whole world, defends this principle.”59 Ultimately, then, Muggeridge held that the orthodox Christian crusade for life against modern materialism could not be sustained by individual partisans striking from isolated catacombs, but required reinforcement from the world’s most ancient guerrilla army.

Despite his often jeremiac appraisals of the “century of bones,” as a poet has described it, Muggeridge discovered in his adopted faith a font of lasting Christian hope. Judging twentieth-century Western capitalism and its culture to be toxic to traditional Christianity and its civilizational mores and institutions, especially the family, he was dismayed by what he saw as the widespread acceptance of a hedonistic mindset and its eugenic implications, thinking that this ethic augured a culture in potentially terminal decline.

Redemption’s Source

Yet Muggeridge remained engaged with his age. Not only did he identify the most pressing manifestations of this materialism’s impact and relate these effects to deeper social, economic, and spiritual causes, but he proposed orthodox Christianity as the best source of cultural redemption. To him, a civilization of love could emerge even from the ruins of a culture that had gotten its death wish, if it was built on the love that founds the sole abiding City.

As distressed as Muggeridge was by the West’s current course, then, he did not despair of God’s providential grace and its ability to redeem his post-Christian time, making him “a tactical pessimist and a strategic optimist.”60 As he wrote, echoing his beloved St. Paul and John Henry Newman:

Whatever the darkness, however profound the sense of lostness, the light of Christ’s love and the clarity of his enlightenment still shine, and will continue to shine, for those that have eyes to see, a heart to love, and a soul to believe. . . . I am a participant in His purposes, which are loving, not malign, creative not destructive, orderly not chaotic—and in that certainty a great peace and a great joy.61

A short version of this article was presented at Muggeridge Rediscovered: The Malcolm Muggeridge Centenary Conference, held at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, on May 22–23, 2003.

Notes:

1. For Muggeridge’s social criticism, see Adam Schwartz, “The Muggeridge Conundrum,” Touchstone (March/April 1998), 39; and David Virtue, “The Collision of Two Minds,” Touchstone (Jan./Feb. 1999), 33. For a synopsis of orthodox Christian opposition to industrial capitalism in twentieth-century Britain, see Adam Schwartz, “Swords of Honor: The Revival of Orthodox Christianity in Twentieth-Century Britain,” Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture 4 (Winter 2001), 19.

2. See, e.g., Like It Was: The Diaries of Malcolm Muggeridge, ed. John Bright Holmes (Collins, 1981), 425, 495; Jesus Rediscovered (Doubleday, 1969), 35–36; A Fireside Chat with Malcolm Muggeridge, ed. Michael Davies (Neumann Press, 1984), 11; Confessions of a Twentieth-Century Pilgrim (Harper & Row, 1988), 49, 57.

3. Jesus Rediscovered, 170. See also Things Past, ed. Ian Hunter (London: Collins, 1978), 52, 83; Like It Was, 497; Jesus Rediscovered, 66, 159, 213; The Most of Malcolm Muggeridge (Simon & Schuster, 1966), 354–355.

4. Jesus Rediscovered, 112. See also Things Past, 161, 53.

5. Jesus Rediscovered, 144; Things Past, 219, 233; Gregory Wolfe, Malcolm Muggeridge: A Biography (Hodder & Stoughton, 1995), 305.

6. Like It Was, 506. See also Things Past, 102; and Fireside, 11.

7. Things Past, 110, 112. See also Like It Was, 476.

8. Things Past, 85; “Operation Death-Wish” (1977), in Orthodoxy, ed. R. Emmett Tyrell, Jr. (New York: Harper & Row, 1987), 410–411.

9. Jesus Rediscovered, 75. See also ibid., 90, 172, 183–184; Like It Was, 512; Confessions, 70; Most, 70; Things Past, 217, 229.

10. Things Past, 72, 164, 217, 227; Jesus Rediscovered, 57, 67, 156; Most, 227, 154–155.

11. Fireside, 66. See also ibid., 35; and Jesus Rediscovered, 67, 158.

12. The Thirties (1940; reprint, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989), 95.

13. Like It Was, 496. See also ibid., 311, 392; Jesus Rediscovered, 77, 89–90, 158–159.

14. Things Past, 140, 227, 238. See also Confessions, 144; and Something Beautiful for God (1971; reprint, Harper & Row, 1988), 13.

15. Like It Was, 521. See also Fireside, 11.

16. Quoted in Joseph Pearce, Literary Converts (HarperCollins, 1999), 396. See also Things Past, 232; Like It Was, 392.

17. Most, 35, 41–42; Jesus Rediscovered, 42. See also The Thirties, 19; Things Past, 233–235; Fireside, 49.

18. Most, 366–367; Like It Was, 496, 512.

19. Like It Was, 481, 506; Things Past, 125–126. See also Most, 230.

20. Fireside, 20.

21. Most, 223.

22. Confessions, 67.

23. Jesus Rediscovered, 63; Something Beautiful, 88.

24. Something Beautiful, 11; Things Past, 72–77. See also Like It Was, 345.

25. Quoted in Wolfe, 71.

26. Fireside, 36–37. See also Jesus Rediscovered, 114–115.

27. Jesus Rediscovered, 156. See also Most, 154–155; Jesus Rediscovered, 150–157.

28. Quoted in Wolfe, 395.

29. Jesus Rediscovered, 78.

30. Things Past, 36.

31. The Thirties, 19; Jesus Rediscovered, 36.

32. Fireside, 38. See also Jesus Rediscovered, 117.

33. Jesus Rediscovered, 207. See also ibid., 64–65, 123, 134–144; Most, 157.

34. Things Past, 179.

35. The essay appears in Most, 152–157.

36. Things Past, 187; Jesus Rediscovered, 205. See also Wolfe, 271.

37. Things Past, 41. See also Fireside, 4.

38. Fireside, 12.

39. Jesus Rediscovered, 203.

40. “Why I Am Becoming a Catholic,” The Times, 27 November 1982.

41. See, e.g., Jesus Rediscovered, 77; Things Past, 216, 228; Fireside, 51.

42. Quoted in Wolfe, 338. See also Something Beautiful, 13.

43. The Times, 2 February 1975.

44. Confessions, 12. See also The Thirties, 40; Jesus Rediscovered, 58, 74–75; Things Past, 212, 229, 245.

45. Things Past, 227–229. See also Jesus Rediscovered, 90; “Death-Wish,” 411.

46. Jesus Rediscovered, 205.

47. Fireside, 54.

48. Things Past, 233–235. See also Fireside, 18.

49. Jesus Rediscovered, 206. See also Something Beautiful, 13.

50. Jesus Rediscovered, 88. See also Confessions, 144.

51. Something Beautiful, 92.

52. The Thirties, 226–227; Like It Was, 357. See also Jesus Rediscovered, 201.

53. See Wolfe, 330, 393, 416; Pearce, 403.

54. Confessions, 142–144.

55. Wolfe, 394.

56. See, e.g., Jesus Rediscovered, 139; Wolfe, 395.

57. Fireside, 20.

58. “Becoming a Catholic.”

59. Fireside, 17. See also ibid., 50; Confessions, 140–143.

60. Like It Was, 479.

61. Jesus Rediscovered, 66; Things Past, 245.

Adam Schwartz is Assistant Professor of History at Christendom College.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor