Standing with Christ

A Response to R. Albert Mohler, Jr.

by David Mills

I told some of you yesterday that the middle part of Dr. Mohler’s talk would set the cat among the pigeons. For one thing, to reject ECT is just not done in polite ecumenical circles. But as a Catholic, I found the paper quite bracing, and not least his claim, certainly not politically correct even in these circles, that there are certainly true Christians within the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches, but that these true believers must in some sense come to the simplicity of faith through means other than the official teaching of their churches. I found that enormously bracing. Such clarity and honesty pleases me because it is so rare and because it is so kind. I do not believe what Dr. Mohler believes, but I am grateful that believing it, he has so loved his neighbor as to say it.

Before I respond to the paper, I want to say one thing about Christian divisions. The scandal of division is not necessarily so scandalous as we tend to think. We are always told that it is a great scandal to the world and a reason people do not become Christians, but I think this is not quite true. I speak as someone who came to Christ in high school but was so badly formed that I only came to a recognizably Christian mind some years later, in my twenties. In fact, I remember, in one of the more idiotic acts of my youth, leaving out the Virgin Birth when I said the Creed in church on Sundays because it seemed to me unnecessary and unproven.

As an unbeliever, and then as a stupid believer, I never found the argument against Christianity that I heard people make from the fact of Christian division the least bit compelling. And that for two reasons: First, it seemed to me obvious that something as old and as big and as complicated as the Church would be divided even if it were true. This seemed to be built into the thing, built into the nature of fallen humanity. This may only express the historical fatalism left over from my Marxist youth, but it seemed to me obvious.

Second, and more important, the argument did not compel me because I saw that the Christians I knew, and the ones I read, clearly maintained the divisions because they were men of principle who would not buy peace at the expense of what they thought to be the truth. They were all one in the love of truth in a world that valued camaraderie and compromise over truth, and I found that integrity compelling. It was for me a sign of the Kingdom. And I found Dr. Mohler’s integrity a sign of the Kingdom.

I feel, I should say, like a living experiment in living with the gulf that J. Gresham Machen described, because I speak as a Catholic serving the Lord at a decisively Anglican and Evangelical seminary. It was a seminary founded about thirty years ago with the aid of people like J. I. Packer and John Stott. (I should say also, having become a Catholic recently, that I speak as someone with great gratitude for the liberality and generosity of the dean and academic dean, who found this person suddenly jumping ship and did not sack him.)

I feel quite deeply and quite personally these stresses we have been talking about in the conference, because my colleagues are people I love and respect, and people with whom I have stood under fire in the ecclesiastical wars of the Episcopal Church, and people with whom I share in a common ministry, but from whom I am separated. We are brothers, blood brothers, who do not eat from the same table, and this is painful. I say this so that you do not think that I express my agreement with Dr. Mohler’s thesis with any pleasure except the pleasure of truth.

To the paper. I am going to address the middle part of the paper, which is the most important for our concern. It is the setting-cats-among-pigeons part of the paper. I should note that in my comments I will be leaving out the Orthodox. All of my comments apply to the Orthodox, but sometimes in a slightly different way, and to make all the needed qualifications would make the argument quite labored and confusing.

Dangers & Differences

I want to make just four comments expanding on his paper. First, Dr. Mohler argues in effect that the sentimental form of conservative ecumenism really covers over serious dangers—not just problems or misunderstandings but real dangers. It covers them somewhat as the snow over a junkyard covers the old cars and hides the ragged metal edges and the broken glass. It is an illusion and a dangerous one—you can put a picture of this junkyard covered with snow on a calendar, but you should not run through it. Reality can hurt, and it is best we know this. Dr. Mohler has said clearly, but not explicitly, that being a Catholic is dangerous, and anything that obscures this fact, no matter how well-intended, is a very problematic enterprise. And I think he is right, as a Southern Baptist, to say so.

Second, Dr. Mohler’s argument implies, I think correctly, that the differences between the traditions are not resolvable except through deep conversion—through a paradigm shift or a change of mind, a radical reorientation or turning around of one side or the other. To put it bluntly, Christian unity would mean the end of Protestantism or the end of Catholicism. I would like to hear him say, “Hail Mary, full of grace,” but if he comes to say it, he will not be a Baptist anymore. He would like me to stop saying it, but if I do, I will not be a Catholic anymore.

I stress this because some advocates of what is often called “the new ecumenism” very naively assume that this new mutual respect, and this agreement on mere Christianity and co-belligerence, will lead to Christian unity because both sides, Protestant and Catholic, are simply a ways apart and have only to move a little to meet in or near the middle. They do not understand the nature of the differences. They think of Protestantism and Catholicism as points on a spectrum and not, as is more the case, as opposite banks of a canyon or opposite shores of an ocean.

Forgive me if I am being unfair to some Evangelicals, but I often hear them talk about the rediscovery of the saints as if this brought them substantially closer to Catholics, and argue that their new love for the saints’ example is enough for Christian unity. They seem to think that a high view of the saints is all that is required, perhaps because, in coming this far, they have moved a long way from the mainstream of Evangelicalism and therefore feel they must be near the center of things. But the saints have a very different place in Catholic theology and piety, which the Evangelical will never ever accept, except by ceasing to be an Evangelical. The two cannot meet halfway; they have different understandings of the saints and different places for them in their faith.

In the same way, many ecumenically open Evangelicals insist that Catholicism would be all right if only Catholics would stop adding things to the Bible, and think this a minor concession. They do not understand—even when you explain it to them—that it is a fundamentally different enterprise to do what they suggest, one that reduces Catholicism to a style of Evangelicalism.

So we cannot meet halfway because we have profoundly different minds and imaginations. The world, this world and the next, looks very, very different to the Protestant and to the Catholic.

Let me just mention one problem that makes our relations even more complicated. My beloved friend and colleague, Steven Hutchens, admitted yesterday that he might be wrong about Mary, as indeed he is. He wins points for open-mindedness, but the Catholic cannot say, in turn, that he might be wrong about Mary, not only because the Marian doctrines are to be held de fide, but because they are integral to what the writer Rosemary Haughton has called “the Catholic thing.”

If Dr. Hutchens is right to think he might be wrong, the Evangelical can grow into Catholicism and so be, on this issue at least, genuinely open-minded. The Catholic cannot be open-minded in the same way without apostatizing. This is an effect of the difference in minds, or imaginations, or paradigms that is often missed or ignored, and makes our conversations confusing and unfruitful. The Evangelical in many cases can offer to be open-minded in the way that the Catholic simply cannot be, not because the Catholic does not want to be open-minded but because he has certain commitments that leave him “close-minded.”

Here I should correct a misleading impression that some seem to have gotten from both Fr. Richard John Neuhaus’s and Dr. Robert George’s addresses, judging from the conversations I’ve heard. Fr. Neuhaus and Dr. George both noted that in Ut Unum Sint the Holy Father has put even the papacy up for discussion, and both said that they did not know what the future unity would look like. But we do know much about what John Paul II’s vision would look like, at least in outline. It will still be papal, with belief in transubstantiation, invocation of the saints, etc. The future of the papacy does not include a revision of the papacy and the teaching of the Catholic Church that would ever please Evangelicals, and probably not please the Orthodox either. One should not hope that Christian unity will be advanced by the pope ceasing to be the pope, which is what some seem to have taken from Fr. Neuhaus’s and Dr. George’s remarks.

Core Problems

Third, extrapolating from Dr. Mohler’s argument, but I think in conformity with it, I would ask if the idea of core doctrines or mere Christianity—even as explained last night by Dr. Timothy George—is actually helpful. I would like to ask you if these ideas, which we naturally gravitate to, are in fact unhelpful and misleading.

I have not worked this out for myself (which is the prudent speaker’s way of saying, “Don’t expect a coherent answer if you ask me about this later”), and I offer it mainly as a suggestion for future thought, but it does seem to me that if the shared core ideas or the commitments of mere Christianity are developed in such radically different ways by the different traditions, these radically different developments will in turn radically affect how the core ideas themselves are understood. The Catholic will therefore mean by “mere Christianity” something significantly different from what the Evangelical will mean.

It is a difference both will often fail to see, not only because with genuine good will they presume agreement, but also because they are both using the same language. If I am right about this—and I offer it only as an intuition or suggestion—the fact that we all develop mere Christianity in such different ways will fundamentally change how we understand the idea and content of mere Christianity itself. If I am right, the idea of mere Christianity—or core doctrines or core ideas—becomes less and less useful as a way of understanding our relation across this gulf.

Fourth, I think neither the Catholic nor the Evangelical (the Mohlerian Evangelical anyway) would accept without great reservation what Dr. Oden has called “the ancient ecumenism.” Remember the four-fold criteria Dr. Oden offered the other night for finding agreement between Catholics and Evangelicals on praying to and/or with the saints. One of his criteria was an appeal to the ancient exegesis of the relevant Scriptures.

For the Catholic, his appeal to the exegesis of the early Christian writers is inadequate because, among other reasons, the Church did not stop developing in the early centuries, and it is only by knowing where she got to that we know which strand of the ancient thought on the matter was the right and the orthodox and the Catholic one. This is not to mention the fundamental difference in minds: The Catholic would look at the church’s liturgical practice as well as to Scripture for evidence of the original Christian teaching, and on this issue it is the liturgical practice that is most revealing. The Catholic would find Dr. Oden’s method inadequate because it does not take account of the development of the whole Church through history.

The Evangelical, on the other hand, would not grant such authority to the ancient exegesis. This Dr. Mohler has said quite clearly, and Dr. Timothy George seemed to suggest last night. His respect for the Fathers does not extend quite that far, because he believes—if I understand him rightly—that the Fathers did not always read Scripture as its authors intended.

In other words, by its method, this “ancient ecumenism” answers the question of unity in ways neither side finds acceptable. I bring this up because an equivocal view of tradition seems to me to be a central claim and a crucial support of much of the “new ecumenism,” but in the end, the new ecumenism seems to me neither fish nor fowl. It is traditional without being submitted to the tradition as a Catholic would wish, and yet claiming more authority for the tradition as the interpreter of Scripture than the Evangelical would wish.

The Evangelical, of the sort represented by Dr. Mohler and many of my colleagues at Trinity, sometimes feels that the traditionalizing Protestant is surrendering belief in a self-authenticating Scripture without realizing it. The Catholic sometimes feels that the traditionalizing Protestant—for whose traditionalizing we say bravo—wants to use tradition without the required commitment. To use an image of Fr. Patrick Reardon’s, their use of tradition is like teenagers having sex in the back seat of the car: They have not reached the level of commitment required before they take the pleasure. A Catholic sometimes feels that the traditionalizing Protestant wants the fun of tradition without paying the price of submission.

I am not sure, if I may pitch my own cat among the pigeons, if it is really a plausible or workable method, this four-fold test of the “ancient ecumenism.” Think of what are called “sex and gender issues,” like headship in the family and the church, contraception, and divorce and remarriage. We have heard the renewal groups in the mainline churches described as bearers of this “new ecumenism.” But their success, as Dr. Oden described it yesterday, is predicated on their complete approval of the headship of women—which both Dr. Mohler and I think a clear rejection of New Testament teaching, and one that fails the four-fold test of the ancient ecumenism.

A renewal movement that tried to restore the ancient Christian practice would go down in flames. But if we—Dr. Mohler and I and the other editors of Touchstone—are right about this, these renewal movements have institutionalized a great error, indeed a rebellion against God’s order, which is really a final barrier to Christian unity. And that is not to mention what would happen to them if they tried to restore the ancient Christian practice of marital chastity, particularly the rejection of contraception.

In other words, the real test of the ancient or new ecumenism will be its ability to restore the once-universal Christian practices that are now countercultural even among practicing Christians. It is not enough—it does not go very far at all—that it has been formed around opposition to secularism and homosexuality, for these are not yet countercultural among Christians.

Is There Hope?

So now that we have lots of dead pigeons lying at our feet and two very satisfied cats, let me close by asking: Is there hope for us together? Is there hope for the fruitful alliance of the hardboiled Catholic and the white-knuckled Evangelical? Is there hope for us together, given these reservations first Dr. Mohler and now I have expressed from different sides?

Well, of course. I agree with everything that Dr. Mohler has said about the cooperation of those who share what he called basic world-view concerns. I think that the last part of his paper was exactly right all down the line. I would add just three points.

First, I think we can take hope in the fact that there are other signs of unity behind or beyond the doctrinal. One is our own shared imagination or mind: the way we understand the world. There, I think, you find us—the sort of people gathered here, I mean—all much closer to each other than our doctrinal commitments would suggest. We are divided, for example, in our understanding of the authority of tradition, but we all look to tradition with a reverent and an open mind. We all sit at the feet of our elders. We all love our fathers. This separates us not only from the modernizing Christians but also from many conservatives.

I can think of two Evangelical patriarchs I know fairly well. They are both very strong Evangelicals, both sons—devoted sons, articulate, learned sons—of the Reformation, but one has a mind that submits itself to history, that looks back, that weighs everything in terms of what has been said before. In fact he told me once that in his twenties he struggled with becoming a Catholic, precisely because he was concerned about the nature of tradition, the authority of history, and so on. Even when he takes a decidedly Reformational point of view, he is always conscious of the entire sweep of history, and only breaks with that sweep of history for (what seem to him) very good reasons, and unwillingly.

But for the other Evangelical patriarch, any question really does come down to him and his Bible. If he came to the conclusion that the Bible taught something, and you said, “But sir, no one in church history has ever thought this,” he would say without any hesitation, “Well, it’s time we got it right.” I am afraid I am not exaggerating. I have had this discussion with him. History has no real weight for him, and he will break with it without a second thought.

These two patriarchs illustrate the different minds. As I said, one thing that does draw us together is this shared imagination and mind we have, of which one example is our looking to history. There is a commonality between me and this Evangelical patriarch and Fr. Reardon and Dr. Mohler, that we do not share with modernizing Christians or liberals, but we also do not share it with many conservatives for whom history has no weight.

Another way of describing the unity we have behind or beyond the doctrinal differences is the one Dr. Mohler mentioned at the end of his talk. It is the presence of a doctrinal mind: a mind that cares about Christian truth and its proper and exact formulation. Here are people you can talk to with some hope of getting somewhere. And this again separates us not only from modernizing Christians—who often, as you know, hate dogma while being among the most wildly dogmatic people in human history—but also from many conservative Christians who think doctrines are merely mind games that help intellectuals resist the Holy Spirit.

There is a real unity and a reason for hope for greater unity in this shared doctrinal mind, this mind that cares about truth. If you are a Catholic, you can recognize this sort of mind in a Baptist—even though you are divided from him very strongly on theological lines—and instantly feel him an ally and a brother. He is your kind of guy, and you recognize him as being different not only from the liberals but also from many conservatives who like your doctrine much more than he does.

Grace & Love

My second addition to the insights Dr. Mohler offered at the end of his paper is that being Christians, and being doctrinally minded Christians, we know how ideas work and how God works. Because we know how ideas work in the human mind, we can accept with some equanimity the errors of our friends. As G. K. Chesterton said, “A bigot is not the man who thinks he’s right—every sane man thinks he’s right. A bigot is the man who cannot understand how the other man came to be wrong.”

And because we know how God works, we do not condemn other believers, however defective their understanding. Each of us knows that if we are right, we are right by an act of grace—an undeserved, an utterly and completely undeserved, act of grace—and we cannot say why others have not been given the grace we have. It is not often for any obvious want of sanctity. I was helped to a serious faith in part by the example of a saintly Baptist deacon, and though I think that now, as a Catholic, I see things and know things that are of the gospel and of God that he does not see, yet he is a saint. The fact that I think I am right and he is wrong has nothing to do with obvious sanctity. It has to do with the gift of grace we simply can’t explain.

Third, the love of Christ itself is a gift of discernment. I think this is what C. S. Lewis meant in the statement Dr. Mohler quoted, though I share his reservations about Lewis’s claim that we are all closer at the center. It does sound and risk being sentimental and sappy. I think that what Lewis was getting at (and putting it, I think, badly) is that the love of Christ itself is a gift of discernment. It helps us know who our friends are, and reminds us that they are our friends even when we have come to points of doctrinal division. This clarifying love is not sentimental: It will speak the sort of hard word Dr. Mohler spoke. But it will help the speaker to say it, and the hearer to receive it, and still remain friends, even brothers.

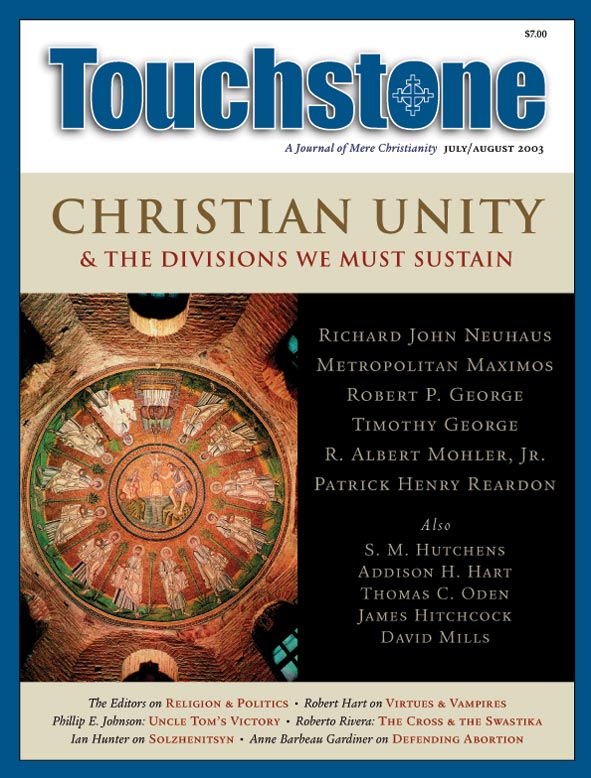

The editors of Touchstone, for example, are a very diverse group, and have sometimes come close to sundering arguments because the divisions are so deep and we are talking about things that matter deeply to both sides. We have had some fairly profound divisions over the place of Mary in particular, of the sort where people are tempted to throw their pen on the floor, storm out of the room, and slam the door on their way out.

Even when we have those sort of disagreements, we have been restrained and set back to work, and keep working together, because we love the Lord and we love each other. We love each other because we love the Lord, and we love the Lord in part because we love each other. We can stand shoulder to shoulder—in our case in the production of a magazine of co-belligerence—though we know that some of those in that line are profoundly mistaken, because we are all together looking at the Lord Jesus Christ.