A Stunted Ecclesiology?

The Theory & Practice of Evangelical Churchliness

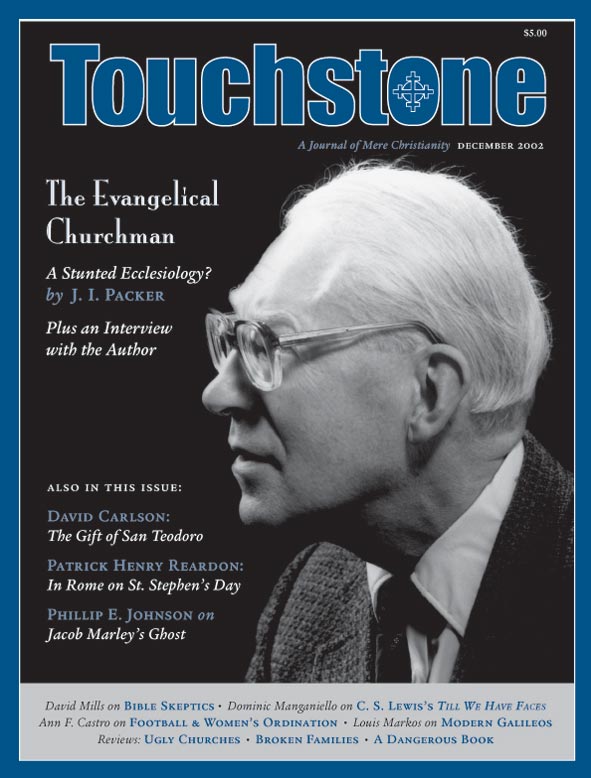

by J. I. Packer

About a half-century ago North American evangelicals began to speak of the evangelical church. They still do. The phrase denoted, and denotes, the worldwide fellowship of congregations and Christians who profess evangelical beliefs and maintain an evangelical style of piety and pastoral care, centering upon conversion, Bible-reading, evangelism, fellowship with God in assurance and trust, and fellowship with other believers in the shared joy of born-again life. The currency of the phrase marks the mutation of the former self-image of evangelicals as the marginalized faithful remnant within liberal-led Protestantism into a sense of being truly the core of God’s church on earth.

Evangelicalism is more and more viewing itself as the main stream, in relation to which non-evangelicals, whether so by adding to the biblical faith or subtracting from it, are deviating eddies, and evangelical vocation is more and more seen as involving prayer and labor for the leavening and reinvigorating of non-evangelical communities by evangelical truth. This mutation continues to broaden and deepen. It shows a remarkable recovery of confidence and, so I think, of churchliness too.

What is in the mind of evangelicals when they speak of the evangelical church? They are not using the singular noun in what would be a secular way, that is, to signify a statistical and organizational collective, though of course the global evangelical fellowship is that, and may be so viewed if sociology is one’s concern. But in fact their use of this phrase is voicing the same sort of claim to authenticity as Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians express when they identify themselves as belonging to the church. This small c use of the word church (large c reduces it to a group label) carries the thought of the one body of Christ on earth, of which all believers are in some sense members, but which takes its most proper form in the circle of communion to which each of the adjectival qualifiers (Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and now evangelical) is pointing.

Believers using any one of these three distinguishing labels for self-identification express thereby, in an informal and subtextual way, their belief, not that God is content to have three communities of saints side by side, but that here is the particular road that ideally all God’s people would be taking together. The ecumenical exchanges of the past century have brought an awareness of this churchly inkling (often not more, but never less) as undergirding the sometimes perplexing phenomenon of separation justifying itself; and when evangelicals speak of the evangelical church, the same inkling is involved. There is here, in fact, a recognizable renewal of the sense of churchly reality that lay at the heart of the sixteenth-century reformation.

A comparable renewal has taken place among evangelicals in Britain, and I see myself as a product of it. English by birth, Canadian by choice, Christian by conversion and Calvinist by conviction, I speak as an evangelical who finds his home in the worldwide Anglican church family precisely because historic Anglicanism in its essence represents evangelical churchliness so well. (Present-day Anglicanism in the West is dreadfully out of shape and out of sorts, but that is another story.) In what follows, however, I attempt to generalize about all global evangelicalism as it is today.

This, be it said, is a tall order, for since the Second World War evangelicalism has become a massive network of pulsating energies, largely charismatic in style and constantly adjusting its cultural forms. Statisticians say there are something like half a billion evangelicals in the world, twice as many as there are Orthodox and almost half as many as there are Roman Catholics, and to speak representatively for this multinational pluriform constituency is not an easy task. But I shall try my best, and I apologize in advance to any evangelicals who may feel I am off-key as far as they are concerned.

The Principles of Evangelicalism

What does evangelical mean on evangelical lips? It is an umbrella word, covering and connecting belief, spirituality, purpose, and action, both personal and corporate. The quadrilateral account of evangelicalism as biblicist, cross-centered, conversionist, and evangelistic has gained wide acceptance in recent years. I myself profile evangelicalism in terms of six belief-and-behavior principles, thus:

1. Enthroning Holy Scripture, the written word of God, as the supreme authority and decisive guide on all matters of faith and practice;

2. Focusing on the glory, majesty, kingdom, and love of Jesus Christ, the God-man who died as a sacrifice for our sins and who rose, reigns, and will return to judge mankind, perfect the church, and renew the cosmos;

3. Acknowledging the lordship of the Holy Spirit in the entire life of grace, which is the life of salvation expressed in worship, work, and witness;

4. Insisting on the necessity of conversion (not of a particular conversion experience, but of a discernibly converted condition, regenerate, repentant, and rejoicing);

5. Prioritizing evangelism and church extension as a life-project at all times and under all circumstances; and

6. Cultivating Christian fellowship, on the basis that the church of God is essentially a living community of believers who must help each other to grow in Christ.

I think this profile remains accurate, and I will assume it in the rest of this essay.

The evangelical emphasis on the uniqueness of Holy Scripture as the verbalized revelation of God, and on its supreme authority over God’s people, is sometimes misunderstood as a commitment to the so-called restorationist method in theology. This method sets tradition in antithesis to Scripture, and places the church’s heritage of thought and devotion under a blanket of permanent suspicion, thus reducing its significance to zero and encouraging all who seek truth and wisdom from Scripture to dismiss tradition as mere morbid pathology and a hydra-head of destructive mistakes. There is no denying that individual evangelicals of highest integrity, if sometimes limited learning, have followed this method, at least in their own view of what they were at.

The Role of Tradition

But the authentic evangelical way has always been to see tradition as the precipitate of the church’s living with the Bible and being taught by the Holy Spirit through the Bible—the fruit, that is, of the ministry that the Holy Spirit has been fulfilling in the church since Pentecost, according to Jesus’ own promise. Seeing it so, mainstream evangelicals value highly what they see as the positives of tradition, as witnesses their constant drawing of inspiration from the thought and service of such past leaders as (for instance) Augustine, Bernard, Luther, Calvin, Edwards, Whitefield, Wesley, Spurgeon, Carey, and Hudson Taylor. Similarly, they treasure the hymns of such as Isaac Watts, Charles Wesley, and John Newton, and many also value liturgical forms from the classic Anglican Book of Common Prayer and the literature of Celtic spirituality—all of which are elements in the tradition of the church. Jaroslav Pelikan’s felicitous description of tradition as “the living faith of the dead” in contrast to traditionalism, “the dead faith of the living,” is, so far, a thoroughly evangelical estimate.

Because evangelicals know that Christian minds, like Christian hearts, are as yet imperfectly sanctified, they expect some of the Christian community’s traditions to prove mistaken and misleading, and they see the need to test all of them accordingly. But because evangelicals know that the Holy Spirit’s guidance into truth was and is a reality, they expect to discover that tradition is full of truth and wisdom, and to find that even controversy in the church’s past, however bewildering and unhappy in the short term, brought clarity out of confusion about what honors God, benefits souls, and builds the church. Thus they treat tradition as an archive of past ventures in expounding and applying the Bible, and so as a resource to help them in their own exegetical and theological work.

Evangelicals do not regard tradition, or any part of it, as infallible, any more than they view present-day expositions of Scripture from pulpits, platforms, and podiums, and in printed pages, as in any way infallible. Their goal is canonical interpretation, that is, understanding reached by letting the corpus of canonical writings elucidate itself from within, as the various books link up with and throw light on each other. Evangelicals know that the Bible, thus canonically interpreted, must itself be the assessor of all attempts to expound and apply it. So, as the eighth of the Anglican Thirty-nine Articles says, even “the Three Creeds” (Apostles’, Nicene, and Athanasian) “ought thoroughly to be received and believed,” not simply because the church commends them, but because “they may be proved by most certain warrants of Holy Scripture.”

Evangelicals value tradition, then, as a repository of God-given insight—that is, of ripe skill in listening to what the Bible says and verbally reproducing it in ways that transcend the limitations and relativities of particular cultural backgrounds. Thus, evangelicals value Nicene Trinitarianism and Chalcedonian Christology and Augustine’s analysis of sin and grace, all of which were wrought out in the Greco-Roman intellectual world, and they value also the Reformers’ Christocentric bibliology, soteriology, and ecclesiology, which were wrought out in the intellectual world of Europe’s Renaissance. The evidence for that is the long series of theological treatises and textbooks affirming the general Reformational point of view that have been written during the past half-millennium; though coming from a wide variety of geographical and denominational sources, they are extraordinarily similar in substance on all of these basic themes.

Churchliness & Dissonance

I am making a case for the genuine churchliness of today’s evangelical church, a churchliness that is directly in line with that of the churches that separated from Rome at the time of the Reformation. It is a case, I believe, that urgently needs to be made, both because this recovered churchliness is a significant fact that is often overlooked and because much evangelicalism is in a state of cognitive dissonance about it, affirming churchliness yet retaining an ethos and mindset that seems to observers to deny it. Roman Catholic, Orthodox, high Anglicans, and leading ecumenists often say that evangelicals have an inadequate view of the church. Is that true? In theory, no, but in practice the answer often appears to be yes.

Churchliness means recognizing the centrality of the church and the primacy of the corporate in the purpose of God. The corporate means the negating of individualism in conscientious togetherness of life and action in, through, under, and for our Lord Jesus Christ. Locally, that means mutual involvement, openness, dependence, and ministry within the congregation; ecumenically, it means realizing brotherhood with all Christians worldwide, plus “all the company of heaven” as the historic Anglican Prayer Book puts it, in ongoing adoration of the Father and the Son through the Spirit. The local-church aspect of this is adumbrated in Ephesians 4:11–16; the universal-church aspect is reflected in Hebrews 12:22–24 and Revelation 7:9–12 and 14:1–5.

To be sure, the gospel message individualizes, and faith is always an individual, personal matter, and in the God-centered relationships of love and service formed within Christian community, each person’s individuality and selfhood is deepened and enhanced. At the same time, however, through the ministry of the Holy Spirit, the self-sufficient individualism to which sin in our spiritual system gives rise should be step-by-step snuffed out, and the glory of God in and through the community’s life should increasingly become the focus of each believer’s longings and prayers. This process is precisely a growing into, and an expressing of, churchliness. Is it a regular mark of evangelicals, as it certainly was of the magisterial Reformers? I, for one, have to say: nothing like sufficiently. And that is, in effect, to say that evangelical churchliness is as yet a stunted growth.

Confessionally and conceptually, evangelical ecclesiology is full and strong. Consider, for instance, the account of the church given by the Amsterdam Declaration, representing the common mind of some 11,000 evangelists and church leaders gathered together in the opening year of the third millennium:

The church is the people of God, the body and bride of Christ, and the temple of the Holy Spirit. The one, universal church is a transnational, transcultural, transdenominational and multi-ethnic family, the household of faith. In the widest sense the church includes all the redeemed of all the ages, being the one body of Christ extended throughout time as well as space. Here in the world, the church becomes visible in all local congregations that meet to do together the things that according to Scripture the church does. Christ is the head of the Church. Everyone who is personally united to Christ by faith belongs to his body and by the Spirit is united with every other true believer in Jesus.

The classic exponents of Reformation ecclesiology, John Calvin of Geneva and Richard Hooker of England, would have nothing major to add to that. Yet, as was said, observers will feel there is cognitive dissonance here: Evangelicals who subscribe to such statements do not seem in practice to rate churchliness a factor in full-orbed Christian discipleship, and rarely do they display a personal formation that is fully churchly. Strong individuality within an equally strong frame of corporateness is indisputably the New Testament ideal for Christian living; why then do evangelicals, strong as they are on individuality in Christ, appear weak when it comes to the corporate awareness that should flow from seeing the church as central in the plan of God? What is the problem here?

In broadest terms, this problem of today has three sources. First, evangelicalism was always in part reactionary against Roman Catholicism, and reaction restricts and constricts those reacting. Evangelical rejection of the Catholic mode of churchliness, which is essentially sacramentalist, breeds a tendency to undervalue churchliness as such. Out goes the baby with the bathwater. Second, reinforcing this, European pietism, which has decisively shaped English-speaking evangelicalism since the eighteenth century, was very much a reaction against the deadness of state churches, and in effect redefined churchliness as close fellowship among spiritually lively groups—a view that evangelicals readily embrace without considering its sectarian overtones. Third, twentieth-century wrenching of leadership out of evangelical hands and away from evangelical principles, which has significantly deadened some older denominations, has given new appeal to the pietistic (even separatist) path. This is how Christian concern to cultivate spiritual life has come to hinder the converted from developing a fully churchly heart.

Stunting Elements

To be more specific, there are five elements in the characteristic evangelical mindset of our time that work against thorough realization of what has been called the “abundance ecclesiology” of Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, where the church is declared to be the fullness of Christ, the beloved bride for whom he laid down his life, and is to grow as a single new man in Christ (you can hardly have a more corporate image than that!), moving always into the maturity that is the measure of Christ’s own stature (see Eph. 1:23; 4:11–16; 5:25–27). All five are matters of proper Christian priority that have unhappily triggered improper reactionary antitheses.

Factor one is evangelical salvation-centeredness. No one should fault evangelicals for their loving attention to the task of unpacking the gospel message that “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners” (1 Tim. 1:15). Nothing is more important than that the gospel is fully grasped, and exploring it and emphasizing it is a thoroughly churchly activity. But it has led to a habit of man-centered theologizing, which sets needy human beings at center stage, as it were, brings in the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit just for their saving roles, and fails to cast anchor in doxology, as Paul’s expositions of the gospel lead him to do (see Rom. 11:33–36; 16:25–27; Eph. 3:20–21; 1 Tim. 6:13–16; cf. Rev. 5:9–14).

Too often we evangelicals relegate the truth of the Trinity to the lumber-room of the mind, to be put on display only when deniers of it appear, rather than being made the frame and focus of all adoration. The church then comes to be thought of as an organization for spiritual life support rather than as an organism of perpetual praise; doxology is subordinated to ministry, rather than ministry embodying and expressing doxology; and church life is thought out and set forth in terms of furthering people’s salvation rather than of worshiping and glorifying God. The antithesis is improper and false, to be sure, but the man-centered mindset is real, and is one facet of a stunted churchliness.

Factor two is evangelical word-centeredness. No one should fault evangelicals for valuing Scripture and doctrine and preaching in the way that they do—or, at least, used to do, for catechism, adult Bible schools, and serious learning of the historic faith are currently in eclipse among us, to our own great loss. But our stress on text and talking has marginalized and dumbed down the sacraments, so that their message about the crucified and living Lord as the life of the church is muffled, and the Eucharist becomes an extra, tacked on to a preaching service, rather than the congregation’s chief act of worship, as Calvin and Luther and Cranmer thought it should be. The word-sacrament antithesis, most certainly, is also false, but evangelicals’ disproportionate word-centeredness is a fact, and is a further facet of a stunted churchliness.

Factor three is evangelical life-centeredness—using “life” in the spiritual sense whereby, in historic pietism as in Holy Scripture, it means responsive, satisfying personal fellowship with God, the fruit of regeneration in the heart and the first installment of the coming bliss of heaven. No one should fault evangelicals for flagging this as the most vital matter of all, doubly not when they, and those to whom they speak, belong to moribund congregations or denominations that settle for something less than spiritual life in their adherents. Martin Bucer, the Strasbourg reformer who midwifed Calvin’s understanding of the Lord’s Supper and helped Cranmer to envision a pastorally adequate Church of England, was the pioneer evangelical thinker in this area: He urged that the spiritually lively folk should meet separately as ecclesiola in ecclesia (the little church within the church), to maintain their spiritual vitality in fellowship together.

English Puritanism and German pietism took this up in a big way. The perennial trouble, however, is that, by a process as understandable as it is regrettable, growing care for the health of the smaller body reduces concern for the quickening and renewing of the larger unit. Evangelicals have hewed to Bucer’s line diligently enough for the small group that meets to pray, study the Bible, and share experience to be labeled an evangelical institution, and this unhappy process has been observed to take place in these groups over and over again. Such a narrowing of care is a seedbed of sectarianism and ought never to occur—but it does, and it has to be listed as one more facet of modern evangelicalism’s stunted churchliness.

Parachurch & Independence

Factor four is the parachurch-centeredness that is nowadays virtually an evangelical trademark. No one should fault evangelicals for creating a plethora of parachurch ministries; they are needed if the work of the kingdom is to get done. Parachurch agencies supplement the ministrations of the church with auxiliary activities and specialist skills that local congregations lack. Missionary societies were first in this field, followed by societies for specialized service at home, and from these beginnings has grown today’s vast mix of parachurch bodies, ranging from the very small to the very large (Campus Crusade, Focus on the Family, the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, and such like). Everyone should be glad they are there, and rejoice in the work they do.

But sadly, by the same narrowing process described above, these agencies of God’s kingdom draw interest, prayer, enthusiasm, and money away from the wider-ranging, slower-moving, less glamorous realities of congregational life, so that the parachurch body comes to have pride of place in supporters’ affections and in effect to be their church. Here, again, the antithesis is improper in theory but potent in practice, and must appear as yet a fourth facet of evangelicalism’s stunted churchliness.

Factor five is the independent-church syndrome, which matches parachurch-centeredness but goes further. Evangelicals have created many independent congregations in recent years, and I would be the last to criticize them for doing so: After all, church-planting as such is a sign of health and growth. Nor should we fault the theology behind independent churches, which is that Christ the Lord himself must rule and guide each congregation by his Word and Spirit as directly as possible. Yet a problem lurks here. Independent congregations are such through declining connectional bonds with other congregations—such bonds, I mean, as synods, councils, superintendent ministers, bishops, and court systems provide. Abuse of these bonds, as seen, for instance, in American Anglicanism’s current agony under rogue bishops, is an argument not for abolishing authority networks, but for constitutionalizing them more wisely and electing operatives for them more discerningly.

No antithesis should be posited between connectional structures and the congregation’s responsibility to follow the will of Christ, for structural links holding congregations together as the apostles’ personal ministry once did would seem to be part of his will, whatever local problems may arise from acknowledging this. Links of this kind, within an agreed-upon frame of creedal soundness, are signs of the organic, space-time continuity of the body of Christ on earth, the catholic visible church of which each congregation is an outcrop, sample, and microcosm; such signs should not be cast off. When they are, sectarianism seems to threaten, and another aspect of stunted churchliness has made its appearance.

My hope is that in this new century the churchliness of evangelicalism will become evident. As my analysis shows, the difficulty here is more practical than theoretical. Evangelical ecclesiology is not stunted, but evangelical churchliness as a mindset and an ethos is, and without rethinking and adjustment this will continue, so that the credibility of the evangelical claim to mainstream status as church will remain suspect and perhaps be forfeit. Will the evangelical church gain credibility through change at these key points? Or will it continue partly at least to deny its name? We wait to see.

J. I. Packer is recently retired professor of theology at Regent College, a prolific author, and a well-known pastor, teacher, and lecturer. For more details about his fifty years in Christian ministry, please see the interview in this issue.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

28.3—May/June 2015

Of Bicycles, Sex, & Natural Law

Describing Human Ends & Our Limitations Is Neither Futile Nor Unloving by R. V. Young

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor