Shakers Without Salt

John E. Murray on the Loss of Religious Charisms

The first Shakers came to America from England in 1774, and until early in the nineteenth century, their numbers grew at a rate comparable to that of the earliest Christians or of the present-day Mormons. Their missionary efforts spread the faith throughout New England, and in 1800 news of the great Kentucky Revival inspired them to send a team of missionaries there who met with great success. Eighteen of their communities lasted at least 75 years, and many lasted more than a century.

Their growth slowed dramatically, however, and their number peaked some time about 1850, after an intense few years of spiritual activity known internally as the Age of Manifestations, and then began a steady decline. Today about as many Shakers keep the faith in Sabbathday Lake, Maine, as came to America two and a quarter centuries ago.

What accounts for this cycle of growth and decline? The earliest Shakers demanded much from their fellow Believers—celibacy, surrender of private property, public confession of sins—but also delivered a high-reward religious experience. Shouting, speaking in tongues, writing prophecies from the long dead, ecstatic dancing, and other such spiritual phenomena provided powerful evidence that to live as a Shaker placed one in close proximity to God. A moral of their story is that a high-cost, high-reward religion is eminently viable.

While scholars have proposed many causes for their decline, most can be disposed of easily. The reason wasn’t celibacy; the sect grew many fold while practicing celibacy. It wasn’t contamination by contact with markets; in fact, they used markets cleverly to expand their wealth and reserve time for worship (by employing hired hands to produce necessaries and tradables).

No—after the 1840s the Shakers simply lost their charism. Maintaining a high-cost, high-reward church is no small task, and an active spiritualism would seem to be an especially high-maintenance spirituality. They had shaken, and danced, and screamed, and grown, but they stopped doing all these things at about the same time.

After mid-century, their religious life changed dramatically. By later in the nineteenth century, Stephen Stein wrote in his sympathetic general history of the Shakers, The Shaker Experience in America, their worship resembled standard Protestant services: Scripture reading, sermon, and hymns. Therein lies the key to the Shaker decline: The descent into generic, nonsectarian worship doomed them. Why would people want to become Shaker, with all its attendant sacrifices, if the religion they experienced could be had down the road in a typical Christian church that only expected them to show up occasionally and not jettison their family and wealth?

After the Shakers withdrew from active spiritualism, people who were seeking religious experience simply did not find the benefits of being a Shaker worth the high costs. And so the Shakers dwindled in number.

Shakers & Catholics

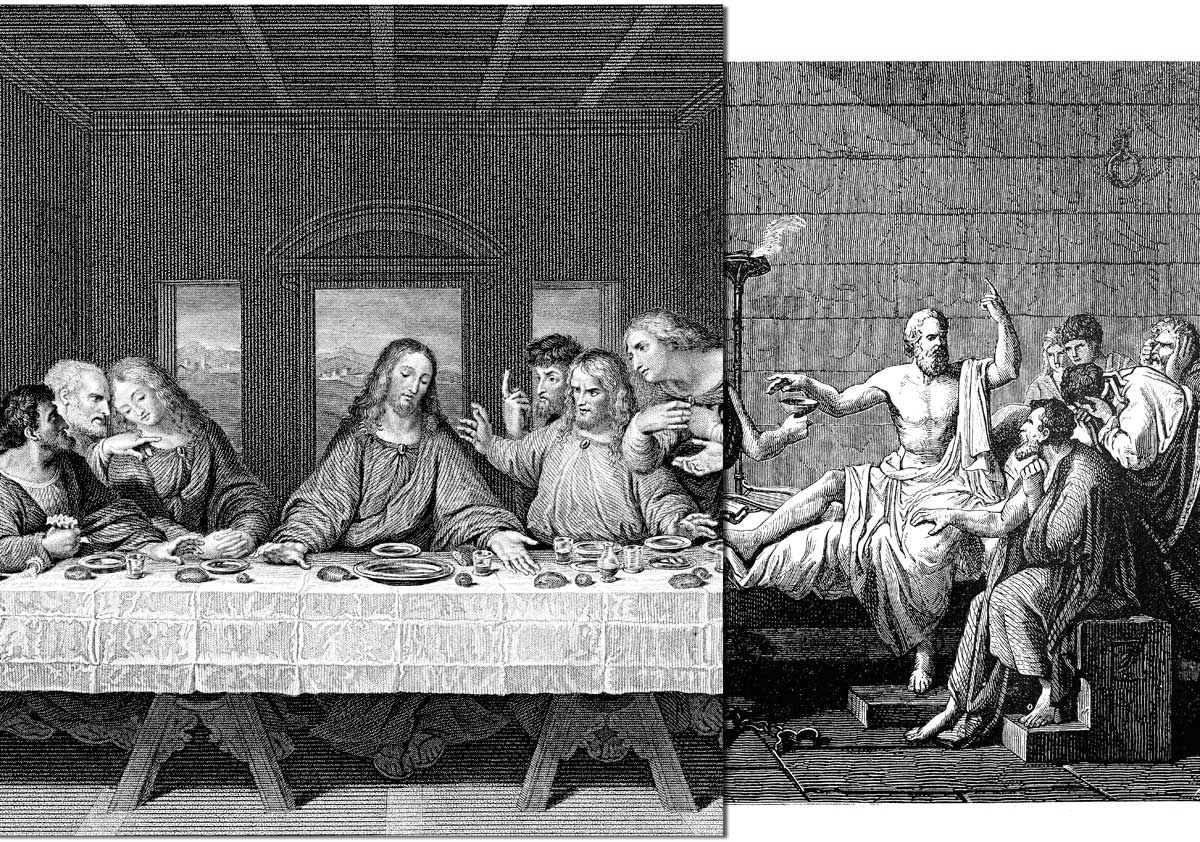

How similar is the arc of Shaker history to the recent history of American Catholicism? Prior to Vatican II, worship was unified and Catholics knew their charism, which was in fact an entire worldview, involving sin, grace, and redemption. In particular, it centered on the Real Presence in the Eucharist. In church buildings, sight lines of perspective ran directly to the Tabernacle, as real a demonstration of the centrality of the Eucharist to church and Church alike as could be imagined. Bells at the Consecration and patens at the reception reinforced the literal belief that the hosts had now become Christ’s body. All provided powerful evidence that to live as a Catholic placed one in close proximity to God.

Just as the Shakers had created problems for themselves, after Vatican II, Catholicism gave up much of what made it distinctive. Liturgically this was immediately obvious to at least one outside commentator, Jaroslav Pelikan, who as a Lutheran observed that the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy marked the end of the liturgical reformation—and the reformers had won. The result was lex orandi, lex credendi with a vengeance.

It was but a short step from the reformed Mass to the more recent claims of one Jesuit theologian that the “ultimate real presence” resides in the folks in the pews. In my diocese of Toledo, the head art and architecture official, a priest, was quoted in the local paper as desiring that “we should reverence Christ in each other and not make a beeline for the Tabernacle.” Such faithlessness indicates a loss of charism—exactly what the Shakers experienced.

Nobody needs another rant about the state of Catholic Liturgy, and it is beyond my competency to make theological arguments regarding it. However, as a social scientist, I have to wonder about the empirical consequences of what the English Dominican Aidan Nichols calls “the liturgical abuses that have been so sorry an aspect of Western Catholicism in the last thirty years.” If a serious, active body of Christians like the Shakers declined following their loss of charism, why would we expect things to be any different for the Catholics?

The sociology of religion can help explain why two prominent efforts to make the Mass more user-friendly had the unintended consequence of driving attendance into the ground. First, the reason for lay attendance at Mass seems to have changed from presence at bloodless sacrifice to joining in the gathering of the community. Second, the two great commandments seem to have been reversed, so that exhortation to greater love of neighbor has eclipsed (the word is Jesuit theologian Edward Collins Vacek’s) love of God.

The resulting shift of focus from worshipping God to socializing with man has made the Mass like any other activity pursued in large groups. Presumably, the revisers intended to make the Mass more attractive, but by giving short shrift to its defining characteristic—bringing together God and man—their changes actually gave layfolk more reasons than ever to sleep in on Sunday mornings.

With the expansion of the Liturgy of the Word and the de-emphasis of the Liturgy of the Eucharist, what Catholics experience resembles even more that Shaker death knell—a generic Christian Scripture-sermon-hymn worship service—just as Pelikan foretold. No longer did the Mass offer the high reward symbolized by the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist and all the things that went with it, such as special devotions and prayers, mysterious liturgies, and dim churches lit by candles.

In their place Catholics have gained ad hoc com-mentary, homilies on the importance of social work, choirs that expropriate prayers properly belonging to the people, entry and exit of various groups of people, and hand-holding. The combination makes Mass attendance a chore for many Catholics. Truly, as Andrew Greeley has observed, “Lay people must love the Eucharist to come back to this kind of stuff.”

Future Consequences

Given this state, the future doesn’t look good. After all, as Pelikan implied, the experience of the Protestant mainline provides as good a forecast as any. In The Churching of America, Roger Finke and Rodney Stark describe the consequences of conducting a low-demand, low-reward faith: United Methodists, down 11 percent in the last two decades; Presbyterians (USA), down 22 percent; Episcopalians, down 23 percent. Nor are these recent phenomena. From 1940 to 1985 the mainline denominations’ share of all Americans attending church was in sharp decline as well.

The Evangelical experience could hardly be more different. To take one example, the most recent data from the Church of God in Christ (COGIC), a prominent African-American denomination, show an increase in membership of nearly 10 percent per year, for two decades. Members of the COGIC now outnumber Episcopalians and Presbyterians (USA) combined. Other Evangelical denominations achieved similarly astounding growth rates from 1940 to 1985, from a growth rate of 32 percent for Southern Baptists to that of 371 percent for Assemblies of God. A key to their growth is their sense of distinctiveness.

Much of the difference in mainline versus Evangelical fates can be traced to differing emphases on the importance of a church’s distinctive identity. Throughout the twentieth century, faltering mainline denominations desperately sought mergers with each other in the name of ecumenism. The most consistent characteristic of merging denominations, besides dramatic declines in membership, was, according to opinion surveys, a lack of perception on their members’ part that their church had a unique identity.

Recently the Wall Street Journal reported that several mainline denominations have commissioned extensive marketing research surveys to see what their faithful want and are following this up with ad campaigns to restore “brand” recognition of what each denomination is about. The fundamental problem ignored in this process is that several of these churches are at the same time pursuing ecumenical initiatives that would allow sharing of clergy, fuzzing of any remaining doctrinal boundaries, and, in general, removal of such distinctions as would lead to “brand” recognition. Rather than trying to understand their loss of charism, it seems, these churches would muddle along without any.

The consequences of generic religion as seen in Shaker history and in mainline denominations are emerging in American Catholicism as well. By one rough measure, the Catholic Church in America is holding its own. The number of Americans identifying themselves as Roman Catholics has risen from 55 million in 1989 to 62 million in 1998, or at about the same rate of increase as the American population as a whole.

On the other hand, weekly Mass attendance, a more refined measure of something that officially remains an obligation for Catholics, has plummeted from about 75 percent in the 1950s to half that today. Most of the decline occurred in the late 1960s, just after implementation of the Vatican II reforms. Pockets—large pockets, like the archdiocese of New York—may have attendance rates closer to 20 percent. And needless to say, we are all familiar with the “vocations crisis” among priests and religious.

Grim Trends

The loss of distinctiveness that came in the wake of Vatican II, and in particular, the transformation of the Mass from sacrifice to gathering, and its emphasis on love of neighbor to the virtual exclusion of love of God, must have played a role in these grim trends. Prior to the council, the Catholic Church, although huge, had many characteristics of a sect—not in the pejorative everyday meaning, but in the strict sociological meaning that stands sect in contrast to church. The Catholic Church was exclusive, intensely otherworldly, and made its followers aware of their close relationship with God (and Mary, the angels, and individual saints).

It required much of its followers: lifelong monogamous marriage, preferably to a fellow Catholic, weekly attendance, frequent Communion and thus confession, and abstinence from meat on Fridays. It was, in short, a high-cost, high-reward religion, and it prospered.

Some who deny the importance of quantitative measures of religious activity suggest that the quality of religious experience has improved for Catholics, who can now hear Mass in English and participate in all kinds of lay ministries. The Shakers offer some perspective on the notion that dipping one’s toe in the water and scuba diving are more or less the same thing. While few Shakers remain, the interest of many others in things Shaker has led to what Stein calls the “World of Shaker.”

The World of Shaker is a congeries of satellite historical, commercial, and educational enterprises that touch on the edge of the Shaker world but are distinct from it. Auctions of Shaker-made furniture, catalogs of knocked-off furniture, books, and all variety of kitsch constitute this most interesting phenomenon of popular culture.

The World of Shaker is part of what Stein further calls the “myth of Shaker,” the image of the Society as serene, idealistic, and ingenious. As one proponent of the World of Shaker writes, “when we look at them, we see something of ourselves.” Such attempts to erase the distinction between being a Shaker and being a fan of the Shakers hammer home the vast difference between the two. What the Shakers considered most crucial to their way of life—celibacy, common property, public confession, and spiritualism—repels most Americans and indeed most denizens of the World of Shaker.

But the Shaker experience was of whole cloth: Ripping out a thread, however colorful, leaves one with only a thread. The parallel I observe here is with the notion of the “good enough Catholic,” who would like access to the easy and pretty parts piecemeal without engaging the entire experience. This approach might be better described as the World of Catholic.

A Sign of Hope

But let me offer a sign of hope taken from the sociological literature on the vocations crisis among the religious orders. As is well known, membership in Catholic orders, especially of nuns, has been falling even faster than the numbers of mainline Protestants. From a peak of 175,000 sisters in 1965, fewer than 100,000 remained in 1995, and that does not begin to describe the demographic shifts toward more elderly congregations of nuns.

Interestingly, not all congregations are shrinking. Sociologists of religion Roger Finke and Patricia Wittberg have applied the same social scientific theory that I used above to explain the Shaker decline to examine why some religious orders have declined, in terms of their ability to attract new members, while others have not. Certain patterns emerge, differentiating the growing from the declining orders, that are remarkably similar to those characteristics that distinguish growing from declining Protestant denominations.

Orders that (1) maintained a continuity to their pre-conciliar spiritualities, (2) maintained a formation process for novices that excluded other orders, (3) tended to live together in physical proximity, and (4) did not join the liberal Leadership Conference of Women Religious had significantly more members in formation than other congregations, and the magnitudes of difference were huge—factors of two to four. Sister Wittberg summarized: “Historically and currently, those orders that have retained distinctive charisms based on some particular spiritual emphasis have been the most successful in avoiding the periodic extinctions that have afflicted religious communities.” And in their most recent joint work, Finke and Wittberg suggest that it is these orders, a source of renewal in troubled times past, that offer the greatest potential to lead Catholicism back to a vital, growing, high-tension faith.

For a Christian church to direct its faithful in the first instance toward love of God, as its Founder recommended, is hard work. It seems that he graces our churches with particular gifts through which to praise him. Concentration on the divine might be easier with fewer worldly distractions that would occlude those gifts. Yet the pleasures of the world can all too easily replace an active love of a sometimes reticent God. Bound together in a church with fellow sociable human beings—all made in the image of One who loves human beings—it is understandable how the one might be conflated with the other.

Our history as religious beings suggests, though, that to forego special charisms for praising God in favor of rather ordinary social interactions in the guise of loving our neighbor dooms both efforts, to pray and to gather.

John E. Murray is associate professor of economics at the University of Toledo. An earlier version of this essay was given as the address at the annual Catholic Faculty and Staff Assembly at the university.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor