Necessary Doctrine by David Mills

Feature

Necessary Doctrine

Why Dogma Is Needed & Why Substitutes Fail

by David Mills

Many perfectly serious Christians hate, just hate, to be thought “dogmatic.”

You know the sort of man I mean. He will end a discussion of first principles

by earnestly reassuring everyone with whom he has been arguing of his deep respect

for all those who disagree with him, with an eagerness that suggests not so

much a respect for differences as a fear that others may think him too sure

of his position.

I have heard some very conservative Christians end such a discussion—of

first principles, mind you—by declaring that all views on the subject

are of equal value and then looking all around with the perky smile of someone

who expects to be praised. I once heard a man finish explaining the inescapable

necessity of believing in the divinity of Christ with the sentence, “Of

course, this is only my opinion.” If I remember rightly, I could hear

a sigh of relief from the others.

What Makes Them Nervous

It is the specifically Christian doctrines that upset this sort of Christian.

Such Christians are themselves on many other matters very dogmatic: They believe

that eating ground glass is stupid, that you should not run in front of moving

trucks, and that hitting babies is wicked. They believe these, the last especially,

to be eternal and unchangeable truths and will say so in public.

But for some reason they do not like to say in public anything exclusively Christian.

Like those who boast of their belief in the authority of Scripture but are so

afraid of being thought “fundamentalist” or “literalist”

that they rarely quote a word from the Bible, these Christians (who are often

the same people) believe in a gracious God who loves mankind, but they do not

want even to talk about how that grace is given to men, or who exactly is the

Jesus who gives it, or how he is related to the Father and the Spirit, or (especially

to be avoided) how those who have received God’s grace are supposed to

live, or (even more to be avoided) what actions will separate us from that grace,

or (most to be avoided) why he is the only Savior of mankind and the others

imposters.

They like their doctrines “filed by title,” with the content left

unspecified. They like to talk about “the Incarnation,” but are

less comfortable saying “He was made man,” because that implies

“He, and no other, was made man” and “He, and not Allah, or

Buddha, or any of the Hindu pantheon, was made man,” and these imply “I,

though an unworthy sinner, know the truth, and you don’t.”

As I said, it is Christian doctrine that quiets their voices, lowers their eyes,

removes the conviction from their faces, and drives them to find some alternative

to saying out loud the stark and inevitably divisive words of the Christian

doctrines. They may well believe them, but they do not like to speak as if they

do. It would be useful to reflect on why they do this, but in this essay I want

instead to explain why their usual alternatives to doctrinal conviction do not

work.

When they explain their objection to doctrine, they usually insist that a concern

with right doctrine destroys both the unity of the Church and (sometimes or)

her ability to serve the world. They will point to the obvious faith of other

Christians and say that they do not want to be parted from them by a mere difference

in a few words, and they will declare that the world’s needs are far too

great to spend time disputing a few abstract ideas.

At the same time, and as a sort of theological support for this rejection of

theology, these people usually suggest that believers need a more immediate

and fluid relation to God, uninhibited by doctrinal restrictions. On the liberal

side, the former Episcopal bishop of Newark once said in his helpfully straightforward

way—he at least never minded being thought dogmatic—that doctrines

are merely “images that bind and blind us all.” On the conservative

side various charismatic leaders have been fond of saying that “theology

divides, but experience unites,” and of dismissing a theological argument

as “a mind game.”

Both treat holding to dogma as something that less enlightened people do. Dogma

is for the spiritual and moral dullards, people who do not have the vision of

the liberal or the revelation of the charismatic. People who cannot let go of

the past hold to the doctrines.

The same attitude reveals itself among mainline Christians in the now ritual

appeals to “our unity in diversity and diversity in unity” and (still

a staple after all these years) “dialogue” and (for that New Testament

effect) koinonia. It can be seen in its mildest form in the pained

look that crosses a mainline Christian’s face when someone is so ill-mannered

as to suggest that something might be true, even if he is careful not to add

that something is therefore wrong.

This attitude can also be seen in the pitying look many a charismatic leader

will give anyone who wants to judge some charismatic phenomenon by the words

of the Fathers. The questioner will be told that he is “quenching the

Spirit” or even “resisting the Spirit” because he wants to

discern what the Spirit is doing, using the truths he has revealed to us in

Scripture.

Now, many such Christians, especially the questing and questioning liberals,

are not nearly so hostile to doctrine as they honestly think they are. One is

allowed, in fact expected, to be dogmatic about liberal causes and enthusiasms,

but to demand continued dialogue when the liberal cause has not yet been won.

So dozens of Episcopal bishops want the Church to continue to talk about approving

homosexuality, which has not yet been officially approved—almost, but

not quite—but demand that every parish in their dioceses accept women

priests, which has been officially approved. The issue on which they

have not yet gotten their way is an issue to be settled through dialogue; the

issue on which they have gotten their way is a triumph of justice and true Christianity,

and dialogue therefore forbidden.

And even their appeal to dialogue on the still contentious issue depends on

a very dogmatic assertion of the nature of the Church as a body that should

not be divided by doctrinal disagreements. When they plead for more dialogue,

as if they were asking for something doctrinally neutral, they implicitly declare

that the continued institutional unity of the body is more important than its

unity in doctrine, which is to say, they insist on their own doctrine of the

Church without admitting it.

Divisive Doctrine

By “doctrine” I mean a statement about reality, natural and supernatural,

a description of what one believes to be true, not what one feels or suspects

or intuits or hopes or wishes. Doctrines explain how the world began, why it

is the way it is now, and where it is going. By “dogmatic” I mean

a type of conviction that the Christian takes for reasoned and humble certainty

and the world takes for arrogance.

The Christian doctrines are both elaborate and specific, even in the short form

of the Nicene Creed. The Christian doctrine is not just “Jesus is God’s

Son,” but that he is “one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten son

of God, begotten of his Father before all worlds, God of God, Light of Light,

very God of very God, Begotten, not made, Being of one substance with the Father,”

and so on. This statement about reality is both complex and detailed.

These doctrines are so elaborate because they express in propositions the truths

of God’s revelation, which comes to us first in a Person and then in a

very long book, as understood and articulated by many very learned and wise

and holy men, who had to answer a number of very dangerous errors so precisely

that no one could make those mistakes again even by accident. (In other words,

so that in the future such beliefs would be heresies and not honest mistakes.)

They are so specific because God acted in specific men and specific events.

He did not send fallen man a philosophy of life; he sent his only Son. And he

did not send his only Son as a spirit who spoke from the clouds, but made him

incarnate of the Virgin Mary. And this God-man did not just teach people for

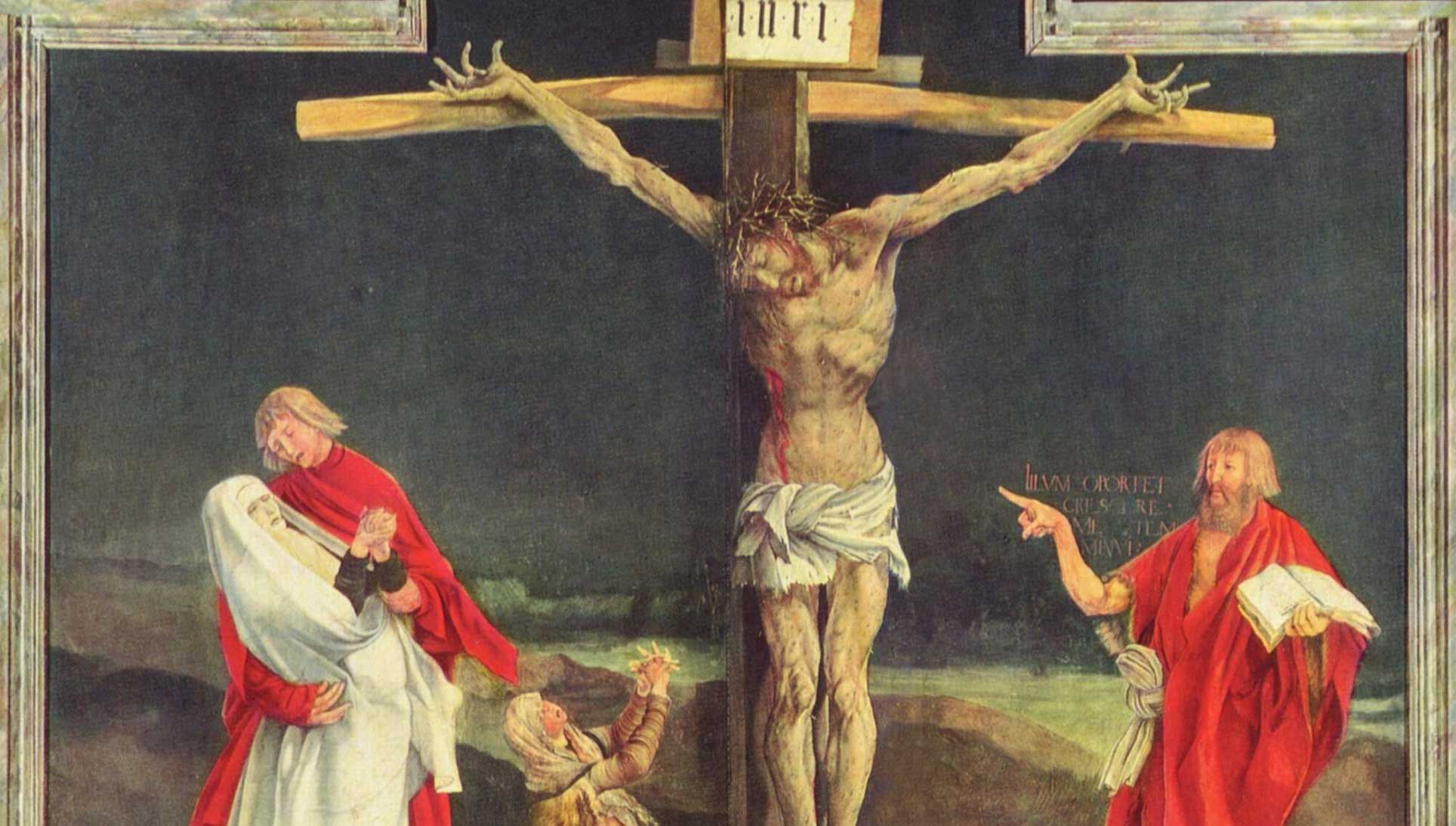

a few years and then disappear; he suffered, died, was buried, and rose again

on the third day. The doctrines are specific because the reality is specific.

Because Christian doctrine is both so elaborate and so specific, modern American

Christians tend to feel the whole collection is a bit overdone or academic or

of interest only to people who care about that sort of thing. They mean well:

They love Jesus and they just do not see why they should worry about doctrine.

It looks irrelevant. True religion can’t be that complicated.

But let me note another irony, similar to the fact that people who hate dogma

are inevitably themselves very dogmatic about a lot of things. Christians who

dislike dogma because it is so complicated will spend thousands of dollars and

hundreds of hours to learn all about the intricacies of the law or the chemical

processes of the digestive system or the way a jet engine works—because

they can see the point of that intricacy.

They are fascinated by the dogmatic complexity of the things they care about.

They expect the law to be complex, but for some reason they expect religion

to be simple.

Chesterton’s Monk

But religion ought to be even more complex than the law, because it deals

with even more aspects of human life. It has to answer many more questions.

As G. K. Chesterton put it in Orthodoxy:

This is why the faith has that elaboration of doctrines and details which

so much distresses those who admire Christianity without believing in it.

When one believes in a creed, one is proud of its complexity, as scientists

are proud of the complexity of science. It shows how rich it is in discoveries.

If it is right at all, it is a compliment to say that it’s elaborately

right. A stick might fit a hold or a stone a hollow by accident. But a key

and a lock are both complex. And if a key fits a lock, you know it is the

right key.

This is also why Christians insist on thinking about their faith. If you have

the key to the code, you will use it to decode the messages you receive. You

will use it to find out what you should know. “Suppose,” Chesterton

wrote in Heretics, “that a great commotion arises in the street

about something, let us say a lamp-post, which many influential persons desire

to pull down.” (Heretics, the “prequel” to Orthodoxy,

is a collection of short articles on contemporaries such as H. G. Wells,

George Bernard Shaw, and Rudyard Kipling.)

A monk is asked his opinion and is knocked down for beginning, “Let us

first of all consider, my brethren, the value of Light. If Light be in itself

good—”. Everyone rushes for the lamp-post and pulls it down in ten

minutes, and then

they go about congratulating themselves on their unmediaeval practicality.

But as things go on they do not work out so easily. Some people have pulled

the lamp-post down because they wanted the electric light; some because they

wanted old iron; some because they wanted darkness, because their deeds were

evil. Some thought it not enough of a lamp-post, some too much; some acted

because they wanted to smash municipal machinery; some because they wanted

to smash something. And there is war in the night, no man knowing whom he

strikes.

So, Chesterton concludes, “gradually and inevitably, today, tomorrow,

or the next day, there comes back the conviction that the monk was right after

all, and that all depends on what is the philosophy of Light. Only what we might

have discussed under the gas-lamp, we now must discuss in the dark.”

Doctrine, in other words, is like light: The more of it you have, the better

you can see. Those who insist on all these elaborate and complex doctrines merely

prefer walking in the full light of day to groping about and stumbling through

the gloom. We want to know not just that “God is love,” which can

mean nearly anything, but that the second Person of the Trinity died for our

sins and still rose from the dead. The first does not help us to see, the second

is the light by which we can see where we ought to go—it is, if you will,

the light unto our paths.

Doctrine Is for Sinners

Were we perfect, we would not need doctrine, though I think even the perfect

might well write creeds just for the joy of putting into words what they know

about their God. The Bible itself begins with the representative man and woman

walking and talking with God in the Garden, and ends with the redeemed crowded

round his throne singing his praises. Neither is said to have written systematic

theologies, but the latter at least sing him praises that are essentially doctrinal.

But we are not perfect. We are far, far more likely to err than to get things

right. We need doctrine, and yet it does not seem to do us much good. It does

seem pointless at best and pernicious at worst.

Doctrinal differences have broken friendships, destroyed families, divided churches,

even brought nations to war. Doctrinal certainty has led perfectly normal people

to kill and torture other people. A concern for doctrinal precision and the

inevitable squabbles seems to be a luxury the Church can no longer afford, when

the world finds the churches increasingly irrelevant to its needs and interests,

and souls are driven away from Christ by the sight of Christians brawling over

words.

There is a legitimate case to be made against doctrine. One can argue quite

persuasively that Christians should abandon it before their arguments hurt more

people and they waste more time and money arguing with each other when they

should be ministering to the world.

This would be true, it feels to most of us moderns as if it ought to be true,

but it isn’t. The Church cannot be unified, nor can it witness effectively

to the world without a common doctrine. Doctrine is another name for truth,

which means for reality, and human institutions will stay together and will

act effectively only if they live according to truth, for otherwise reality

will eventually destroy them. If a church abandons doctrine, people will get

hurt and more time and money will be wasted.

If any group of Christians is to be one body in any meaningful sense, and

if they are to get anything useful done, they have to be dogmatic. To stop

worrying about right doctrine is a luxury the Church cannot afford.

The Unity of the Church

First, the Church needs doctrine to ensure its unity. Almost all the Western

churches are deeply divided on fundamental questions, and those responsible

for keeping them alive usually propose four alternative sources of unity: a

common ethical standard, a common religious experience, a common ecclesiastical

process, and a common institution. None, however, can create unity when the

members disagree on doctrine. The mainline churches have all tried them in the

last three decades, and there is no reason for anyone else to try them again.

Though they will, of course, the alternative being repentance.

Now, each of the four methods I have just listed, judiciously applied, protects

a church from the natural disintegrating pressures suffered by any fallen human

institution. Working together or praying together or talking together does sometimes

reveal a deeper doctrinal unity obscured in the heat of battle by superficial

contradictions, differences in language, personal ambitions and hatreds, or

unquestioned assumptions.

There is something to be said for each of them, but they can only discover and

protect a unity that exists already, as happens when Baptists and Roman Catholics

meet to protest abortion and find that, though one is holding a rosary and the

other a big King James Bible, they love and serve the same Lord. These methods

cannot themselves produce unity.

If anything, by replacing a common doctrine, they make division and schism all

the more likely, by making everyone’s preferences and tastes and opinions

all the more important. You can pray with a man whose musical tastes you hate

if you are both bound by the same creed, but if you are not bound by an authority

above you who demands that you kneel at his side, you might as well leave him

for someone whose CD collection is similar to yours. You will define “common”

in the most convenient way.

A Common Ethical Standard

The first alternative that mainline Christians usually propose is a common

ethical standard. It is thought that however much people differ from one another

in doctrine, they all recognize the same moral laws. If they disagree about

the Resurrection, nevertheless they agree that murder and adultery and selling

nuclear weapons to developing nations are wrong. One does not hear this suggestion

very often these days, though several mainline leaders have recently suggested

that environmentalism will bring the Church together.

A common ethical standard cannot produce unity because a common ethical standard

requires a common doctrine. People act in certain ways because they believe

certain things to be true. If they did not believe them they would act differently.

In one of Chesterton’s Father Brown stories, the Master of an Oxford college

tells Father Brown that he prefers the old adage, “For forms of faith

let graceless zealots fight; he can’t be wrong whose life is in the right.”

That can’t be true, Father Brown replies.

How can his life be in the right, if his whole view of life is wrong? That’s

a modern muddle that arose because people didn’t know how much views

of life can differ. Baptists and Methodists knew they didn’t differ

very much in morality; but then they didn’t differ very much in religion

or philosophy. It’s quite different when you pass from the Baptists

to the Anabaptists; or from the theosophists to the Thugs. Heresy always does

affect morality, if it’s heretical enough. I suppose a man may honestly

believe that thieving isn’t wrong. But what’s the good of saying

that he honestly believes in dishonesty?

In the mainline churches, different doctrines have already led to irreconcilable

ethical standards. Those who accept St. Paul’s teaching believe sex outside

marriage is sinful; those who don’t, don’t. Those who believe that

everyone is created in the image of God oppose abortion on demand; those who

believe in the ultimate importance of individual choice support it. Those who

believe that creation reveals God’s intent believe homosexuality is a

perversion; those who believe creation is less significant than “God’s

inclusive love” believe it an honorable life. Without a common doctrine,

there is no common ethical standard, and no unity.

A Common Experience

The second candidate usually invoked to replace doctrine is a common religious

experience. All people, it is thought, have some sense of the divine, some feeling

for the “wholly other” or “ultimate concern,” though

they express it in the forms given them by their culture and experience. Traditional

doctrines are only inherited expressions of this sense, more or less helpful

and more or less relevant. If we can get behind these cultural forms to the

experience they tried to express, we will find that we all worship the same

God.

A common religious experience cannot produce unity because we cannot define

“religious experience” in any usefully limited way—after all,

people have sincerely claimed divine guidance to torture babies. “Experience”

is not specific enough to appeal to. To be able to say that this person has

experienced God but that person has not requires a doctrine, which defeats the

purpose of appealing to experience in the first place.

More importantly, on the testimony of religious people themselves, they do

not experience the same divinity. People who know and follow their religion

are usually more convinced of its unique truth, not less. The cultural forms

and inherited doctrines of each are different because a different God is worshipped

in each.

The proponents of a common religious experience respond by claiming to understand

peoples’ experience better than they, or by making some implausible claims,

as for example that a religion that asserts that God became a specific man who

was raised bodily from the dead to make men and women sons of God is really

the same as Buddhism, which looks forward to the extinction of the self. The

first claim is presumptuous and scientifically dubious, the second just nonsense.

In the mainline churches, the religious experiences have been so diverse as

to suggest that different Gods are being worshiped. Some members experience

God only in Jesus; others experience Him or Her or (I suppose) It in the deities

of pagan religions or in the depths of their own psyches or even (this proposed

by a tenured professor of theology at the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge)

in passionate and varied sexual episodes. Some experience God as the Father

outside us, others as the Mother of whom we are a part. Without a common doctrine,

there is no common religious experience, and no unity.

A Common Process

The third alternative, increasingly invoked as the first two fail, is a common

process, particularly of “dialogue” and (the new, improved version

of dialogue) “conversation.” Unity, it is thought, is not to be

found in our answers but in our questions, in opening ourselves to each other’s

unique insights, in coming to know each other better and in affirming each other’s

experiences and beliefs, with a vague promise that we might possibly come to

agree sometime in the future. Just talking to each other will by itself heal

our divisions.

This alternative also fails. A common process cannot produce unity because dialogue,

if it is sincere, must eventually come to discuss the members’ basic beliefs,

at which point they will have to disagree. About the fundamentals, people will

either agree or disagree. Dialogue cannot heal division if the source of division

is a doctrinal difference neither side can give up.

In the mainline churches, the process of dialogue has only delayed the official

recognition of fundamental differences. Their members may possibly respect each

other more (though possibly not), but respect is not unity. Two men fighting

a duel may respect each other greatly, but they will then try to kill each other.

When a process of dialogue has come to some conclusion in the church’s

legislative bodies—such as the votes in the Church of England and the

Episcopal Church to ordain women—it has only shown how profoundly divided

they are.

Even in conservative circles, Christians are asked to dialogue on women’s

ordination and increasingly on homosexuality. Some people believe that the experiences

of homosexual people cannot change the revealed judgment of homosexual acts;

others believe that the experiences are more revealing than Scripture. Some

people believe that headship in the community is to be held by males; others

that such a restriction is only a historical product that can be changed as

desired to serve new experiences and needs. Once these differences are clarified,

there really isn’t much more to be said. Without a common doctrine, dialogue

can only lead to disagreement and division, but not to unity.

A Common Institution or Heritage

The fourth alternative to doctrine as a source of unity, invoked when even

the third has failed, is a common institution. Unity of doctrine, ethical standard,

religious experience, and institutional process are all held to be impossible,

but it is thought that irreconcilable doctrines may be held together by shared

allegiance to the Church or the tradition or ethnic heritage, with the hope

held out that they might someday agree, and the implication that everyone will

change his mind somewhat in the process.

Anglicanism, for example, is said to be “comprehensive” or “inclusive”

(defined as doctrinally agnostic, which as a matter of historical fact is simply

untrue) and its mission to prove that people of profoundly divergent beliefs

can live together in harmony. Doctrinal ambiguity is said to be of the “genius

of Anglicanism,” which would have surprised the Reformers who died at

the stake for their doctrinal clarity and sent others thereto for theirs.

Institutional unity is, admittedly, unity of a sort. It means that no matter

what is preached each Sunday from the pulpit of the various churches, they will

all have the same name on the sign outside, and the same newspapers and pension

funds and seminaries. But all this kind of unity can possibly mean is drawing

the smallest boundary that includes everyone one wants to include, and true

and useful unity is more than the agreement to go about under the same name.

Unity is not a matter mainly of the external signs. I am not united with an

atheist because we both wear deck shoes and button-down collars, or the Holy

Father with a Hindu priest because they both wear colored clothes to lead worship.

It is a matter of what the signs—which often look very much alike—symbolize,

in other words, what doctrines they express.

No institution with a mission can afford such radical diversity or such a depleted

definition of itself. John Ashcroft and Hillary Clinton could both join the

same club, but not the same political party. A chess club could include those

who believe Scripture eternally authoritative and those who believe it must

be revised to satisfy new demands, but a church cannot.

And, as we will see, such a unity inevitably dissolves when an issue must be

addressed and action taken. Some people will prove at some point to have principles

and to expect their church to share them, and to use its influence to further

them. At which point, except for the terminally unprincipled (of whom there

are many, especially among the clergy), members divide and some refuse all appeals

to save the institution by withdrawing their demands.

In the mainline churches, the appeal to membership in the same ecclesiastical

institution has maintained a legal unity in which people grow farther from each

other while maintaining a nominal membership in a common body—until liberalism,

which in its newest forms is inherently intolerant, acquires enough political

power to purge the unenlightened. Even the most ardently “inclusive”

Episcopal liberals have decided that some Episcopalians are going to have to

conform or leave, because their doctrinal commitments are too different, and

therefore divisive, to be included.

Without a common doctrine, a common institution can only be a marriage of convenience,

and one that will almost certainly lead to divorce. Actually, as the liberals

now in power lose tolerance for those who hold to the received view of sex and

orders, it is just as likely to lead to murder, because one partner does not

want to divide the estate and would like to keep it for himself.

The Usual Alternatives

Thus the usual alternatives to doctrine as a source of unity are unable to bring

and hold together the people of the Church. Without a common doctrine, a common

ethics simply does not exist; a common experience produces behaviors too diverse

to call unity; a common process leads to disagreement and division, if it leads

anywhere; and a common institution is not unified in any meaningful sense. Mainline

Christians, and Anglicans especially, now know from painful experience that

none of these can hold a church together.

If the alternatives have failed, perhaps that to which they are an alternative

has more value than people have granted. Perhaps, if the mainline churches are

to be united, both within themselves and with their sister churches around the

world, they must first return to a common doctrine. Then all these things—an

agreed upon ethical standard, a shared experience of the divine, meaningful

dialogue, and a common loyalty to the Church—will be added unto them.

The Church’s Ministry

If doctrine is necessary to hold the Church together, it is also necessary if

the Church is to get anything done. The Church cannot act effectively without

knowing what it believes. It cannot convince its own members to work together

or those outside to come in, if it cannot give them a reason. To reach and to

serve the world, the Church must be dogmatic.

It cannot speak a word of judgment or a word of healing unless it can speak

dogmatically: unless it can say with confidence, “Thus saith the Lord.”

Otherwise its words are just opinions, of no more value or interest than anyone

else’s. And perhaps of less value, as based upon apparently preposterous

claims about the nature of things, which if not true are evidence of stupidity

or delusion.

The Church cannot speak a word of invitation, cannot demand repentance and offer

change and salvation, unless it can say with confidence, “Thus saith the

Lord.” The Church is not the only one offering salvation, and its version

is much less appealing and much more demanding than most versions the world

offers. All it has to offer, its only selling point, is that the story it tells

is true.

An Advocate of Dialogue

A parish I once attended was given as an interim rector an old-fashioned, sentimental

liberal for whom doctrine seriously held was divisive. He did not care what

you believed, as long as you were not so crass as to think your belief was true

for anyone else.

He was a great advocate of dialogue, and a firm believer in the institution

of the Episcopal Church. At statements of definite belief, even quotations from

Scripture, he would wince slightly and suggest in a soft, patient voice that

we should keep listening to each other before coming to any decision,

recognizing our diversity and being willing to give up our own personal agenda

to maintain community.

His elegant correction was usually enough to end debate, but it did not answer the questions that needed to be answered. He could not avoid decisions that had to be made on the basis of a clear and articulated doctrine. When the diocesan convention was to vote on the ordination of practicing homosexuals, his only response was, “That’s going too far,” but he could not explain why it was going too far. To have given a reason would have meant appealing to some doctrine, a practice he had worked hard to teach the parish to avoid.

Not having a doctrine of human nature, or at least not having one he was willing to admit to, he could only respond with a prejudice to a proposal that would either encourage immorality or liberate an oppressed people. He could not answer the crucial question of whether a revealed moral law excludes homosexual behavior or an inclusive God affirms it. To suffering people, he had nothing of value to say, either of correction or encouragement. Recognizing our diversity and working to maintain community did not help him say anything actually useful to the problems his people faced.

Challenging Secular Moralities

And further, without doctrine the Church cannot challenge secular moralities even when it is unified in condemning them. The world has its own doctrines, which only another doctrine can challenge. And the world is usually very clear about what it believes, and what it believes is usually quite attractive, and it will capture the unsuspecting and the naive and the gullible if the Church is not equally clear.

Take the example of the evil of pornography, about which nearly every Christian, whatever his theological commitments, will agree. Speaking to the New York Times a few years ago, Christie Hefner defended the way her father, the pornographer Hugh Hefner, treated women in the pages of Playboy. (Hefner had left her and her mother when she was three, and rarely saw her afterwards.) “In a world in which infidelity, coercive sex in and out of marriage and dishonesty between the sexes are problems that men and women are concerned about,” she said, “this is a man who has been open in his relations and lived a highly moral life” (emphasis hers).

This is not simply an opinion; this is a doctrine of human nature, well and clearly put. It holds that any human relation is justified if it is open and honest. If young women want to sell pictures of their naked bodies and Mr. Hefner wants to buy them and sell them to others, their arrangement is “highly moral.”

This is a clear, coherent, and consistent doctrine of human nature, and only an equally clear, coherent, and consistent doctrine can stand against it. Only another doctrine can demonstrate to the curious young man why he should leave Playboy on the newsstand and forgo the pleasures of staring at the naked bodies of beautiful young women, and thereby protect him from the magazine’s training in evil. He must have a reason not to do what his culture and his hormones urge him to do.

A church without doctrine, however much it instinctively understands the evil of pornography, cannot condemn the pornographer’s “morality” of openness and honesty. It cannot propose an alternative morality or show why the pornographers’ doctrine of human nature is actually destructive of human nature.

To Stop the Pornographer

Instinct and prejudice are not adequate responses to evil, especially as evil can present itself so winsomely. It is not enough to say that such things are bad. You must be able to show why they are bad, and why they must be opposed. “That’s going too far” will not stop the pornographer, the racist, the abortionist, or those who would clone a human being, or rally others to resist them.

To the claim that pornography exploits women, the pornographer responds that the women freely choose to show their bodies and are well paid for it, and a church without doctrine—a church that offers only more dialogue—can offer no convincing rebuttal. With no settled view of men and women, it cannot say with conviction that such a trade in pictures, no matter how “free” or consensual, exploits women, endangers women and children, and defiles men.

A world without doctrine, in other words, is a world that easily justifies the most brutal exploitation. A church without doctrine cannot denounce that exploitation, and can battle evil only with pious hopes for dialogue and high-minded appeals to openness and commitment. Or, as often happens, with condemnation it has no right to give, because it has no reason to give it, and which the world therefore treats with indifference, if not contempt.

Without doctrine, the Church can only appeal to a vague and undefined divinity supposedly underlying all our competing doctrines—a god to which Mr. Hefner can appeal for justification as confidently as Cardinal Ratzinger.

All Is As It Should Be

I have been speaking of the need to have doctrine and be dogmatic, but of course we need not any doctrine at all but the Christian doctrine, by which I mean the Christian doctrine as given and illustrated in Scripture and articulated by the undivided Church and those since who follow in their tradition. Every Christian has a doctrine, and unless it is the Christian doctrine, it will almost certainly be a bad and destructive one.

My former parish had a second interim rector, a process theologian for whom the traditional doctrines prevented Christians from recognizing new truths (his in particular). “All is as it should be,” he began one notable sermon. God willed the Fall, he went on, “in order that man should live in a world of risk.” It was only in a world of risk that man would grow to maturity.

I’m afraid he, a comfortable and somewhat insensitive member of the educated upper-middle-class, thought the idea profound. Apply his idea to a mother whose child lies dying of leukemia. Tell her in her agony that all is as it should be. Tell her that God willed a world in which the fruit of her womb would die, that she should be grateful that she is thus growing into maturity, that as they lower her boy’s casket into the ground she should rejoice that she lives in a world of risk.

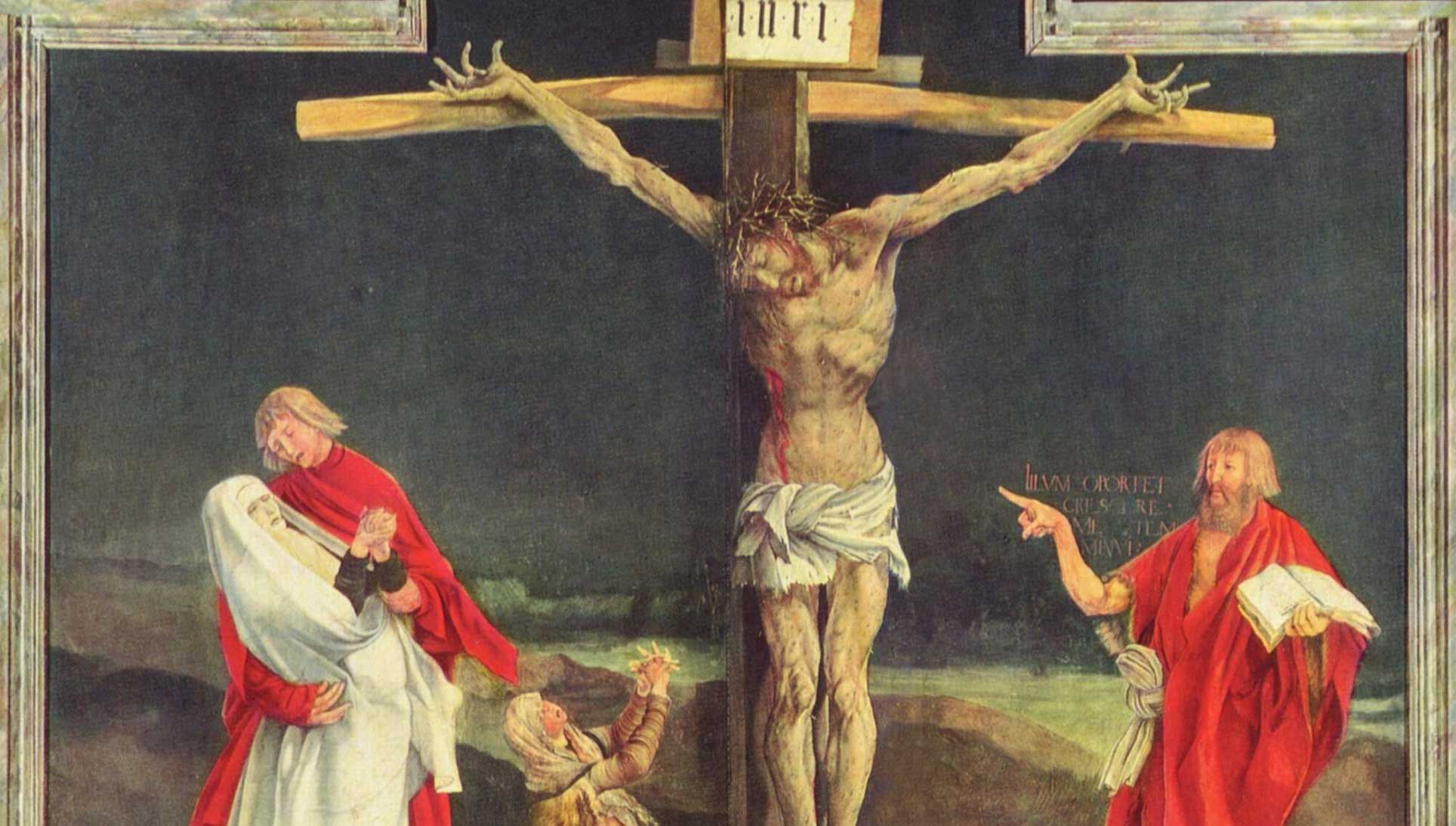

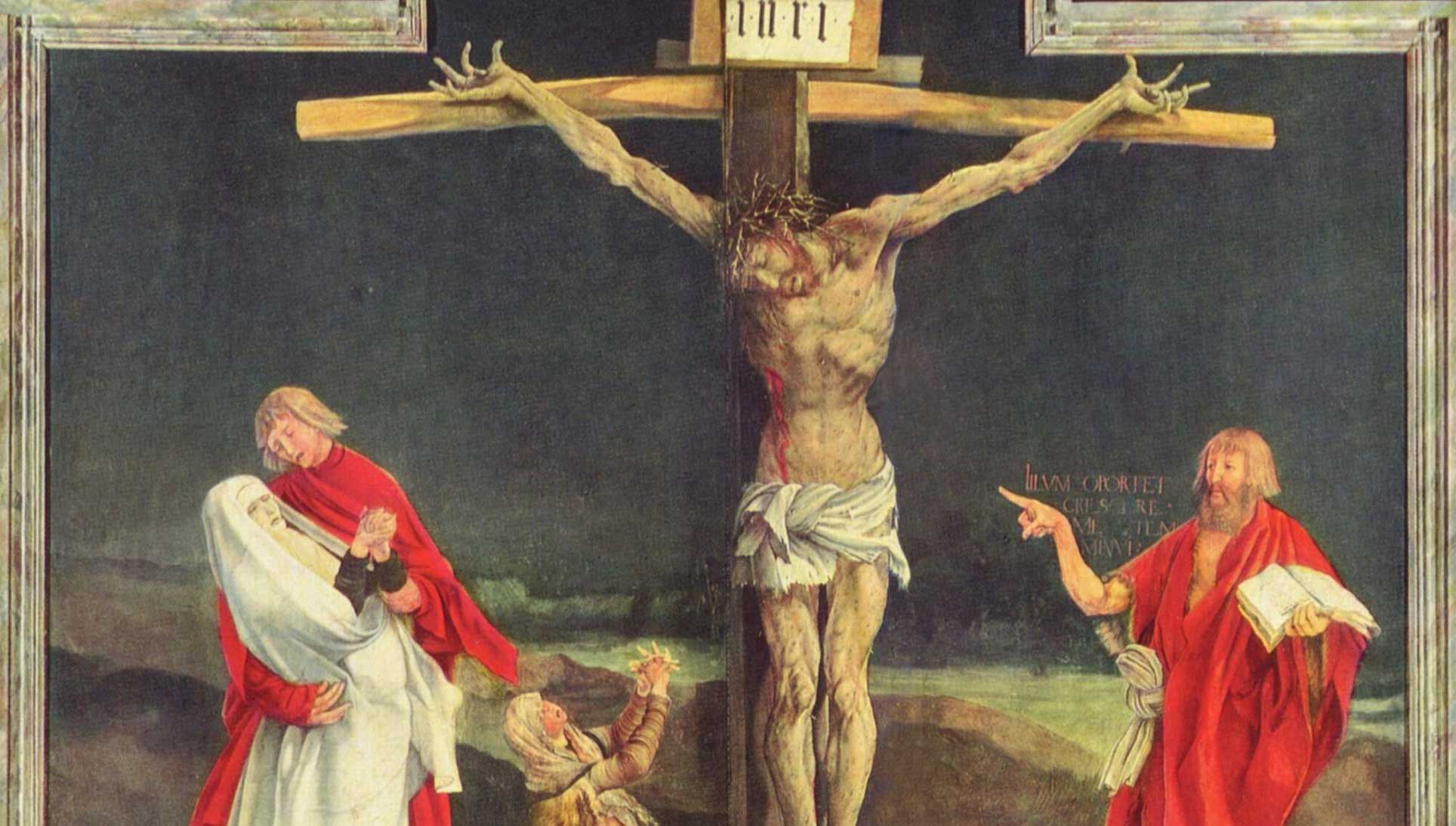

This is not the religion of the Cross and the Resurrection. Its god watches passively while people suffer, offering them nothing but meaningless suffering and then personal extinction. Our God came down from heaven to be tortured to death for the salvation of each one of us. There’s rather a difference.

Hindu or Christian

Without doctrine, in other words, the Church cannot explain pain and suffering, or offer any hope for redemption and release. It can respond only with prejudice or with theories that, however high-minded and rhetorically intoxicating, cannot heal or reconcile or renew. Healing, reconciliation, and renewal require truth, and truth is another word for doctrine.

The religion closest to the contemporary rejection of dogma—the religion that believes, in Bishop Spong’s words, in “a divine power that unites us as holy people”—is Hinduism. It was the British Empire, acting on Christian beliefs about the worth of each individual, that stopped Hindus from burning widows to death upon their husbands’ funeral pyres.

Burning widows was a doctrinally coherent practice, to which neither interim rector could legitimately have objected. If a doctrinally agnostic Christianity guided society, being burned on your husband’s funeral pyre might well be the price you paid for continuing the dialogue, or for growing to maturity in a world of risk.

There, as you roast to death, you might take comfort in the fact that all

is as it should be, while your friends are prevented from saving you by stern

commands to set aside their personal agenda and listen respectfully to those

who think you make a very nice candle.

David Mills has been editor of Touchstone and executive editor of First Things.

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS

full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone

online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

30.6—Nov/Dec 2017

The Messiah's Beauty

on Benedict XVI on the Fairest of the Sons of Men by Michael Martin De Sapio

more from the online archives

30.6—Nov/Dec 2017

The Messiah's Beauty

on Benedict XVI on the Fairest of the Sons of Men by Michael Martin De Sapio

33.2—March/April 2020

The Fairy Tale Wars

Lewis, Chesterton, et al. Against the Frauds, Experts & Revisionists by Vigen Guroian

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor

Support Touchstone

00