Rings of Love

J. R. R. Tolkien & the Four Loves

by Dale Nelson

A tombstone in Oxford’s Wolvercote Cemetery is inscribed “John Ronald Reuel Tolkien / Beren” and “Edith Mary Tolkien / Lúthien.” Because Beren and Lúthien are the names of husband and wife, lovers, in Tolkien’s writings, and because their equation here with Tolkien himself and his wife is firmly founded on his own conception of the man who married the daughter of an Elf-King and a goddess, as a parallel to his own romance, his inscription hints at an answer, differing from the usual ones, to the question of why The Lord of the Rings has been such a meaningful novel for innumerable readers for nearly half a century: It and the invented mythology from which it was developed are permeated by love.

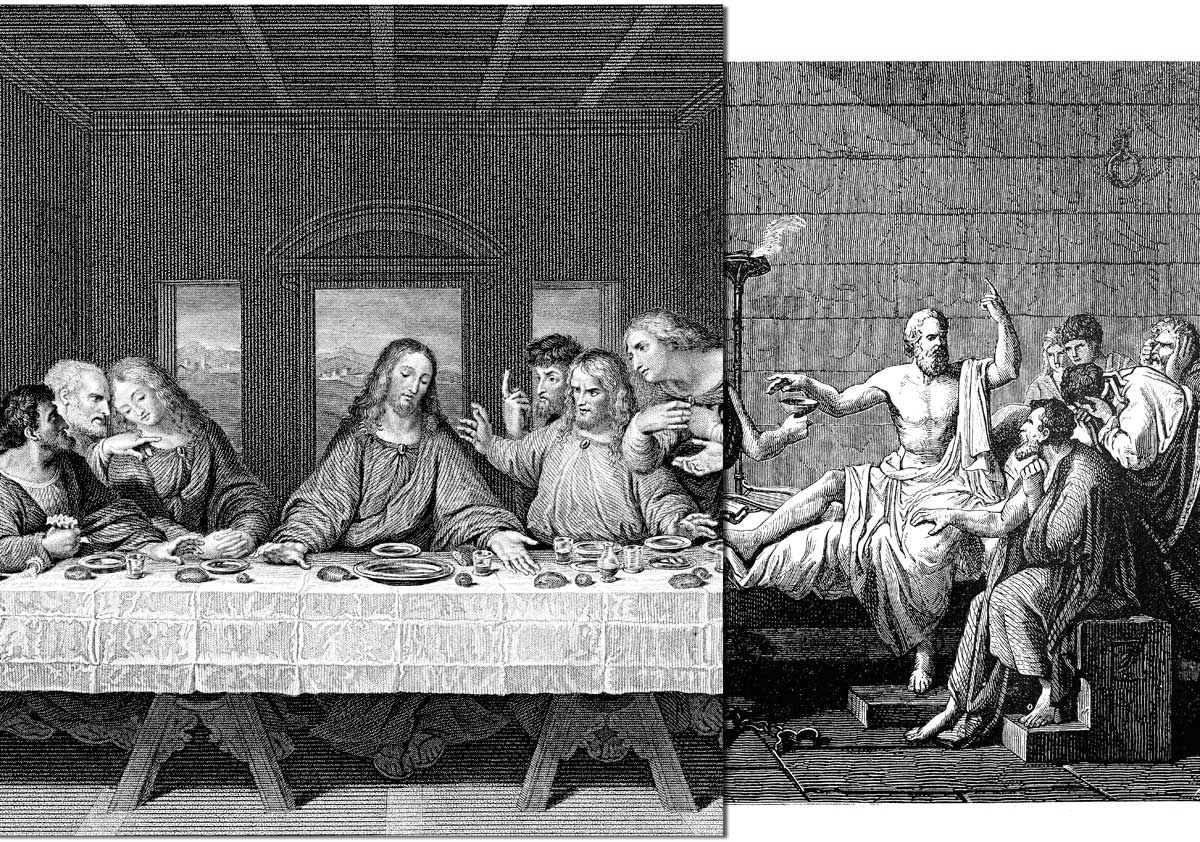

Readers of a 1960 book by Tolkien’s friend C. S. Lewis will remember that the Greeks discerned four loves: storge, philia, eros, and agape. Tolkien has ensured that it’s not just “given” that the conflict in The Lord of the Rings is between good and evil. He has carefully depicted each of these loves, which provide a constant and persuasive contrast to the Dark Lord’s political and spiritual totalitarianism.

An Origin in Love

To the authors of a newspaper profile on him, Tolkien maintained that Middle-earth originated in his love of language. He said that he liked to invent new languages—but they required people to speak them—indeed, required a world; so he would make that world. But attributing the origin of Middle-earth to the love of languages linked it to his public, scholarly life. The Wolvercote monument, and remarks in Tolkien’s letters, show that Middle-earth drew also upon his most private life—specifically upon his experience of eros, the passionate love of man for woman or woman for man.

Tolkien told one of his sons about his young love for Edith in a letter, written after her death. “I met the Lúthien Tinúviel of my own personal ‘romance’ with her long dark hair, fair face and starry eyes, and beautiful voice” in 1908, when he was 16 and she was 19. Very soon after they married, he was captivated by his wife’s dancing, for him alone, when he was an army officer on leave from the Great War, in 1917, and they slipped away to “a woodland glade filled with hemlocks” in Yorkshire. And that moment was the origin of the myth of Beren and Lúthien, Tolkien wrote to another of their sons.

He refused to give the world an autobiography. His nature expressed itself “about things deepest felt in tales and myths.” He went so far as to identify an enchanted moment in a wood as “the kernel of the mythology” of his imaginary world, in a 1955 letter to his American publishers, but he didn’t tell them about his romance. When we put the evidence of these three letters together, we can see that Tolkien believed that his imaginative world owed its existence not only to his love of languages, but also to his love for one woman, Edith Tolkien.

Furthermore, Tolkien’s world of Middle-earth might never have been realized if not for his affection (storge) for his and Edith’s children. The first-published story of Middle-earth was, of course, The Hobbit (1937). It grew out of stories that Tolkien told at home—young Christopher Tolkien called them “Winter ‘Reads’” that they enjoyed “after tea in the evening.” Eventually Tolkien prepared a typescript, but, according to his biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, Tolkien had not finished it before his sons had “outgrown” it and no longer were asking for winter-evening stories—and “so there was no reason why The Hobbit should ever be finished.”

Tolkien dropped it. If not for the intervention of a family friend who knew someone who worked for the publishing firm of Allen and Unwin, Tolkien might have left the book at the point at which he had arrived, the death of the dragon (with no second climax—no Battle of the Five Armies, in which Bilbo Baggins plays such an important role).

As it was, enough had been written that Tolkien was able to finish the book without requiring very much time. The history of Tolkien’s composition of The Hobbit shows that it was grounded in a father’s love for his children; without them, it would not have been. Without The Hobbit, there would have been no call for a sequel—that is, no call for The Lord of the Rings.

The great novel was indebted not only to the eros of Ronald and Edith Tolkien, and to the storge felt by Tolkien for his sons, but also to philia—to friendship, the companionship, esteem, and loyalty of two persons united by a shared enthusiasm (and by opposition to certain foes). The writing of its three volumes, which commenced in December 1937, took 12 years. If not for the friendship of C. S. “Jack” Lewis, Tolkien said ten years after the Rings’ final volume was published, “I do not think that I should ever have completed [it] or offered [it] for publication.”

The interest of Tolkien’s son Christopher and of other members of the Inklings circle, and the patience of publishers, was also of immense importance, but, Tolkien confessed, Lewis “was for long my only audience. Only from him did I ever get the idea that my ‘stuff’ could be more than a private hobby.” Tolkien felt uneasy about the time he took from scholarship and gave to The Lord of the Rings. Jack Lewis, Oxford don like Tolkien, tacitly, perhaps explicitly, assured him that he was right to devote so much energy and care to the fantasy.

Love, then, brought The Lord of the Rings into being. The great narrative itself memorably depicts the Four Loves by means of a number of its chief characters.

Affection & Friendship

Storge is the first of the four loves discussed in Lewis’s book—“the humblest and most widely diffused of loves,” the love of familiar faces because they are familiar, for this is “the least discriminating of loves.” It’s the fondness of parents for children, the fondness of pet owners for their pets.

Samwise, gardener and valet to Frodo, exhibits storge. When the Fellowship of the Ring arrives at the portal of the subterranean realm of Moria, Sam is bitterly sorrowful about abandoning Bill, a pony abused by his former owner but much invigorated by Sam’s attention and a stay in the Elves’ hidden refuge of Rivendell. The narrative’s very last image is of Sam with his infant daughter, Elanor, upon his lap. That is where the whole heroic tale ends, rather than with the fulfillment of Frodo’s vision as he arrives on the splendid, deathless shores of the elven paradise.

Philia is everywhere in The Lord of the Rings. The preservation of the world depends upon the fellowship of the Ring—the fellowship of nine companions who represent the free peoples of Middle-earth: Hobbits, Men, Elves, Dwarves, and a Wizard. The four Hobbits are already friends, and ready to trust the others, but it takes time for Gimli the Dwarf and Legolas the Elf to outgrow their antipathy towards one another.

“Friendship arises out of mere Companionship,” Lewis wrote, “when two or more of the companions discover that they have in common some insight or interest or taste which the others do not share and which, till that moment, each believed to be his own unique treasure.” Gimli beholds the radiant Lady of the elvish realm of Lorien and is overcome.

Say, rather, he is lifted above the ordinary trammels of dwarf-nature by the vision of such surpassing loveliness, not of stone and gem, but in flesh and blood. Thus surprised by Beauty, he becomes open also to the Elves as a people, and, so, to Legolas. Legolas, in turn, begins to learn from Gimli, to see, that subterranean places—Aglarond, Helm’s Deep—may be, or become, realms where beauty dwells.

Eros & Charity

Eros, the third of the four loves described by Lewis, is not absent from The Lord of the Rings. There is, first, the almost entirely offstage romance of Aragorn and Arwen, as one subplot. My guess is that the films will bring forward this love story, as well as a subplot that is developed with much care by Tolkien, the unrequited love of the shield-maiden Éowyn of Rohan for Aragorn. The understated quality of Tolkien’s account of this love story, and the turmoil of the war of the Ring, sometimes cause the Éowyn-Aragorn story to be almost forgotten by readers.

In fact, though, Tolkien wrote with much sensitivity of the sorrowful passion of a young woman who, despairing first of her homeland and her father, and then of the man she longs for, desperately longs to die in battle; of her near approach to death; and of her gradual opening to a new and deeper love.

Elements of this plot are strangely akin to the experiences of some women who, when young, went through a “phase” of bitter dissatisfaction with American society as well as anguished disappointment with their fathers and/or men for whom they felt sexual passion, and who then threw themselves into nihilistic political radicalism or feminism. Tolkien gives us just enough of the further story of Éowyn and Faramir for us to see eros arising in her chastened soul.

Another instance of eros in The Lord must be mentioned: Tom Bombadil and Goldberry. Some readers have objected to the nonsensical endearments—“Hey come derry dol! merry dol! my darling!”—that pour from Tom’s lips as he bustles about, bringing flowers to lay before his “pretty lady.” Why, isn’t it obvious that Tom and Goldberry are perpetual newlyweds? Tom has the giddy happiness of a young man who’s just married his sweetheart. That’s why they don’t have any children! They’ve been together from time immemorial—yet they live as if he’s just brought her home.

The title poem in the collection The Adventures of Tom Bombadil confirms this, telling of Tom catching the River-woman’s daughter and taking her home with him. “Lamps gleamed within his house, and white was the bedding; / in the bright honey-moon badger-folk came treading,” these last being members of Tom’s little kingdom. The poem ends with the image of “fair Goldberry comb[ing] her tresses yellow”—and perhaps one has seen a sheet of sketches drawn by Tolkien with colored pencils, printed in J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator, that includes the slender young Edith, seen from behind, wearing just a petticoat and arranging her hair as she looks in a mirror.

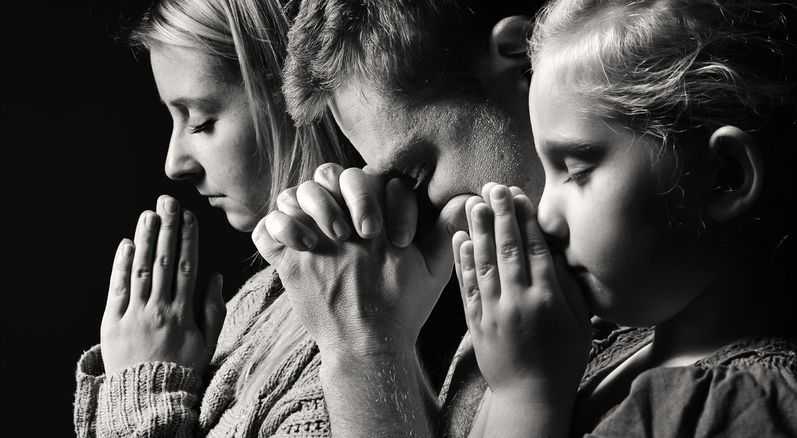

Frodo Baggins, hobbit of the Shire, is the great novel’s chief image of agape or charity, fourth and final of the loves discussed by Lewis. “Frodo undertook his quest” to destroy Sauron’s perilous Ring “out of love—to save the world he knew from disaster at his own expense, if he could; and also in complete humility, acknowledging that he was wholly inadequate to the task,” Tolkien wrote in a letter of 1963.

In the book itself, Frodo has faced the stark fact: “‘It must often be so . . . when things are in danger: someone has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them.’” This self-surrender costs Frodo dearly, although Tolkien, in the same letter, states explicitly what is implicit in the novel, that “Frodo was given ‘grace’: first to answer the call (at the end of the council) after long resisting a complete surrender; and later in his resistance to the temptation of the Ring . . . and in his endurance of fear and suffering.” (The “council” is the Council of Elrond in The Fellowship of the Ring.)

Frodo crawling up Mount Doom inevitably recalls the ascent of Jesus, carpenter of Nazareth, bearing the burden laid on him. Frodo bears an evil load not of his own making to the place where it was forged and can be destroyed. Christ bore the burden of mankind’s sin to the place of the Cross, which was, many Christians have believed, the same place where grew that Tree whose fruit was sinfully plucked, long before. The scene of primordial evil becomes the place of the great sacrifice for the deliverance of others. Only love—only charity—would suffer so much for others.

A Sort of Ritual

Because of its abundant images of storge, philia, eros, and agape, the reading of The Lord of the Rings can become a sort of ritual of the “Stations,” not of the Cross, but of the Four Loves, which refreshes readers again and again. Many people probably think they are simply reading a great tale of adventure, the most captivating fantasy of them all.

It isn’t the adventures and the fantasy that keeps them coming back—so that it’s nothing unusual for people to have read this huge book five or more times. Fantasy, Tolkien said in “On Fairy-stories,” can “recover” for us the reality of “common” things such as fire, bread, tree, iron—freeing them from the “drab blur of triteness or familiarity—from possessiveness.” Such stories take “simplicities,” “fundamental things,” and make them luminous for us.

He does this for no lesser matters than the Four Loves themselves, in The Lord of the Rings. Surely that draws readers back to the book—all their lives. It was written out of love, it was written about love, it will be one of its century’s most enduring literary testaments of love.

Dale Nelson is Associate Professor of Liberal Arts, Mayville State University, Mayville, North Dakota.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on J. R. R. Tolkien from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor