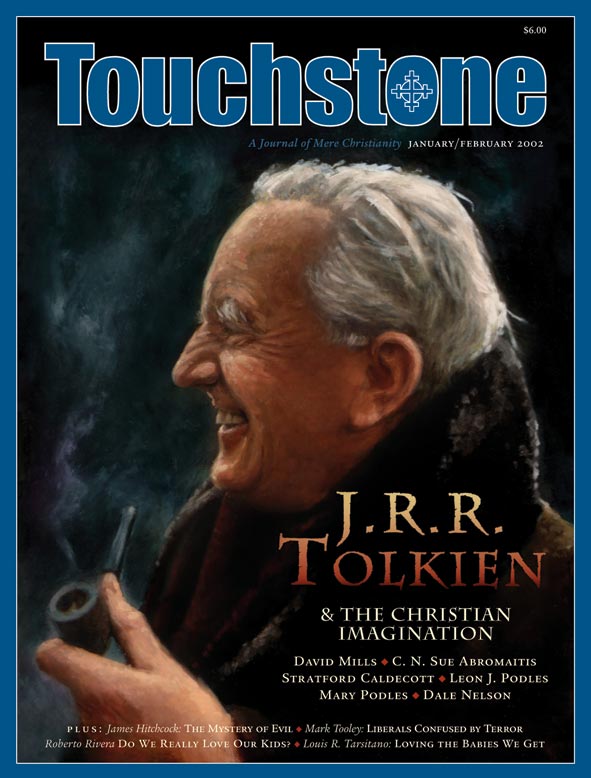

Feature

The Distant Mirror of Middle-Earth

The Sacramental Vision of J. R. R. Tolkien

by C. N. Sue Abromaitis

Most notable about J. R. R. Tolkien’s books is the imagination that created their world. Tolkien himself reflects upon the use of the creative imagination, believing that man, made in God’s image and likeness, shares in the work of God’s creation. At the same time Tolkien is quite aware of his being in a fallen world, one in which he is working against the zeitgeist.

This spirit of the age permeates the artistic depiction of man as the inevitably alienated stranger. The presumption of the age is, in a certain sense, a mixture of two apparently opposed concepts of the real: materialism, reducing all of reality to that which is sense perceptible, and gnosticism, positing a spiritualistic reality available only to the illuminati.

Both mainstream and avant-garde artists and critics adhere to a vision of the world that is materialistic and/or gnostic. Their work essentially denies meaning and harmony, assumes that nothing can be known with certitude, and apotheosizes the self-consciously absurd, nihilistic, hedonistic, anti-heroic, deterministic, and downright ugly.

Ranged against this horror is the sacramental vision that imbues Tolkien’s work, sacramental because Tolkien still sees reflected in the fallen world and its creatures the manifestation of God’s love for man. He believes that all who will open themselves to the epiphanies that surround them can experience this goodness.

Fairy Stories & Fantasy

Tolkien’s literary theory and practice affirm the glorious reality of the world created by God and sees in the beauty of creation proof of the hallowed nature of man. But fallen man needs imagination to perceive this hallowed nature. Tolkien creates his literature to aid that perception. He admits that “one object” of his literary creation is

the elucidation of truth, and the encouragement of good morals in this real world, by the ancient device of exemplifying them in unfamiliar embodiments, that may tend to ‘bring them home’.1

In one of Tolkien’s major theoretical works, the 1947 essay “On Fairy-stories,” he describes the four marks of the fairy story in which “unfamiliar embodiments” can help “bring home” such truth and good morals.

The first mark is fantasy. He uses the word to mean “both the Sub-creative Art in itself and a quality of strangeness and wonder in the Expression, derived from the image.”2 “Fantasy is a natural human activity,” Tolkien concludes.

It certainly does not destroy or even insult Reason; and it does not either blunt the appetite for, nor obscure the perception of, scientific verity. On the contrary. The keener and clearer is the reason, the better fantasy it will make. If men were ever in a state in which they did not want to know or could not perceive truth (facts or evidence), then Fantasy would languish until they were cured. . . . For creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact, but not a slavery to it. (Tree 54–55)

Even as Tolkien defends fantasy as a good thing, he does not ignore the evil uses to which it may be put or its ability to delude the writer or the reader. In another context he comments that

Great harm can be done, of course, by this potent mode of “myth”—especially wilfully. The right to “freedom” of the sub-creator is no guarantee among fallen men that it will not be used as wickedly as is Free Will. I am comforted by the fact that some, more pious and learned than I, have found nothing harmful in this Tale or its feigning as a “myth”. . . .3

His fantasy is neither ill nor evil nor delusive because he sees his art as an expression of man’s sacramental nature. He is using his God-given faculties by imitating God in making. He asserts that this secondary creation is a good act “because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker” (Tree 55). Thus, his aesthetic is informed with the universal moral law even as he praises the goodness of him who created nature.

Recovery & Escape

Similarly, in his explanation of recovery, the second mark of fairy stories, Tolkien’s belief in objective reality that means itself and at the same time is a sign of something else is apparent.

Recovery (which includes return and renewal of health) is a re-gaining—regaining of a clear view. I do not say “seeing things as they are” and involve myself with the philosophers, though I might venture to say “seeing things as we are (or were) meant to see them”—as things apart from ourselves. (Tree 57)

These same premises are apparent in his discussion of the third quality, escape. Tolkien defends it against the critics who disapprove of escape in literature by contending that he is speaking not of “the Flight of the Deserter” but of “the Escape of the Prisoner” (Tree 60). And the prison that he would have his readers escape is “the Robot Age, that combines elaboration and ingenuity of means with ugliness, and (often) with inferiority of result” (Tree 61).

Tolkien comments that there is an attempt to escape from this ugly world in the stories of “Scientificition”; however, what these “prophets” create are worlds of “improved means to deteriorated ends” (Tree 64). Without an authentic teleology, theirs is an escape without a destination.

Moreover, although modern man recognizes that “the ugliness of our works, and of their evil” is something to flee, this too often results in a serious misconception about beauty. We believe that evil and ugliness are “indissolubly allied. We find it difficult to conceive of evil and beauty together. The fear of the beautiful fay that ran through the elder ages almost eludes our grasp. Even more alarming: goodness is itself bereft of its proper beauty” (Tree 65).

Tolkien points out that the healthy perception that beauty can lead man to hell has been lost in the modern world. The dreadful result of that loss is apparent in the deformed morality that pervades the modern age: If something seems beautiful and, therefore, arouses my desire, it must be good for me to have it.

Joy & the Gospel

Tolkien’s analysis of the meaning and nature of the particular aesthetic embodiment of imagination in the fairy story is informed by a consistent rejection of the vulgarity of solipsism and relativism. These reflexes cause modern man to reject his sacramental nature. This rejection, in turn, accounts for the barrenness and joylessness so evident in modern art.

In contrast, as his discussion of the final mark of the fairy story makes clear, Tolkien emphasizes transcendent joy. He asserts that “the Consolation of the Happy Ending”—what he called eucatastrophe—“is the true form of fairy-tale, and its highest function” (Tree 68). He then explains:

The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous “turn” . . . one of the things which fairy-stories can produce supremely well, is notessentially “escapist,” nor “fugitive” . . . [I]t is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. (Tree 68)

This “sudden joyous ‘turn,’” he continues, “does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance.” Instead, “it denies (in the face of much evidence . . .) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”

In the Epilogue to the essay, Tolkien explicitly connects the Gospels with fairy stories. “The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories,” he writes.

They contain many marvels—peculiarly artistic, beautiful, and moving: . . . among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy. (Tree 71–72)

Just as Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Fides et Ratio4 insists that reason can only find its fulfillment in Revelation,5 so Tolkien insists that art can only find its fulfillment in Revelation: The gospel “is supreme; and it is true. Art has been verified” (Tree 72). Just as it is an inherent principle of creation that finite man use his reason, so also does man’s telling stories flow from the nature of creation:

But in God’s kingdom the presence of the greatest does not depress the small. Redeemed Man is still man. Story, fantasy, still go on, and should go on. The Evangelium has not abrogated legends; it has hallowed them, especially the “happy ending.” The Christian has still to work, with mind as well as body. . . . So great is the bounty with which he has been treated, that he may now, perhaps, fairly dare to guess that in Fantasy he may actually assist in the effoliation and multiple enrichment of creation. (Tree 73)

Such enrichment of the primary world is a great achievement. In reading Tolkien’s works, particularly The Lord of the Rings, one senses that his artistry and faith have succeeded in kindling and rekindling, resulting in his writing a story that enriches primary creation.

A Secondary Real World

One of the ways in which Tolkien achieves this effoliation of reality is by situating the events of the book within a secondary world that is true to its mythic self even as it conforms in all important ways with the primary creation that provides the trilogy with its rock and stone, water and air, earth and tree, men and other reasoning beings.

He begins the book with a prologue that explains the background for the story in The Red Book of Westmarch and, in so doing, adds to the consistency of the work by setting it within a history.6 Allusion to records and histories is not unique in this passage.7 His work is filled with poems that tell of events in a variety of pasts upon which characters reflect.

In one of the most moving passages in the book, Frodo, the hero, and his loyal companion, Sam, are sitting exhausted, outside the tunnel through which they must travel to continue their journey to the Crack of Doom, the only place in which the Ring may be destroyed. Their conversation reveals just what a tale means to them. Frodo says that the place seems accursed, then adds, “But so our path is laid.” Sam agrees and says:

“And we shouldn’t be here at all, if we’d known more about it before we started. But I suppose it’s often that way. The brave things in the old tales and songs, Mr. Frodo: adventures, as I used to call them. I used to think that they were things the wonderful folk of the stories went out and looked for. . . . But that’s not the way of it with the tales that really mattered, or the ones that stay in the mind. Folk seem to have been just landed in them, usually—their paths were laid that way. . . . But I expect they had lots of chances, like us, of turning back, only they didn’t. And if they had . . . they’d have been forgotten. We hear about those as just went on—and not all to a good end.” (TT IV:8, 320–321)

These comments occur, of course, in this imagined narrative; at the same time, they have significance that transcends the imagined world. These mythic characters are dealing with the most essential things that all men must confront: fate and free will, victory and defeat, virtue and vice. Moreover, their conversation reinforces a fundamental theme in Tolkien’s work: What is occurring is part of a story, and the story goes on after that part has ended.

After the destruction of the Ring, as Frodo and Sam await what seems to be sure death, Sam speaks:

What a tale we have been in. . . . I wish I could hear it told! Do you think they’ll say: Now comes the story of Nine-fingered Frodo and the Ring of Doom? And then everyone will hush, like we did, when in Rivendell they told us the tale of Beren One-hand and the Great Jewel. I wish I could hear it! And I wonder how it will go on after our part. (RK VI:4, 228–229)

Borne out here is Tolkien’s conviction that “there is no true end to any fairy-tale” (Tree 68).

The Real Hobbit

The stories in these passages are presented as if they were history, a record of human action, important because the actions of rational beings made in the image and likeness of God have eternal significance. This same sense of the high dignity of the person is behind Tolkien’s careful attention to psychological verisimilitude.

The devising of seeming truth is necessary because in a fantasy the writer must convince the reader that the secondary world with its characters is real. Tolkien adapts most of his characters from traditional lore, and he stays true to the mythic ethos that each has. Moreover, he creates his own mythic rational being: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.”8

In this description of Bilbo’s home, Tolkien makes sure that the reader recognizes the uniqueness of this being, this Halfling (The Hobbit 10). All who meet Hobbits, whether Wizards, Elves, Ents, Dwarves, Orcs, Men, Barrow-wights, Nazgul, even Sauron, are surprised by their valor. Gandalf says, “Hobbits really are amazing creatures, as I have said before. You can learn all that there is to know about their ways in a month, and yet after a hundred years they can still surprise you at a pinch” (FR I:2, 72).

That many underestimate them because of their love of comfort gives rise to one of the many themes of the novel: “It is shown that looks may belie the man—or the halfling” (RK V:1, 28).

The themes that arise from the events of the novel are recognizably human. For example, Tolkien depicts the allure of evil even for those who would be virtuous. When Gandalf the Wizard asks Bilbo if he intends to keep his promise to leave the Ring, the central symbol of evil, to Frodo, Bilbo answers in an uncharacteristic manner:

“Now it comes to it, I don’t like parting with it at all, I may say. And I don’t really see why I should. Why do you want me to?” he asked, and a curious change came over his voice. It was sharp with suspicion and annoyance. “You are always badgering me about my ring. . . .”

Bilbo flushed, and there was an angry look in his eyes. His kindly face grew hard. . . . “It is my own, I found it. It came to me.” “Yes, yes,” said Gandalf. “But there is no need to get angry.”

“If I am it is your fault,” said Bilbo. “It is mine, I tell you. My own. My precious. Yes, my precious.” (FR I:1, 42–43)

After further struggle with Gandalf, an externalization of his psychomachia, Bilbo surrenders the Ring: “A spasm of anger passed swiftly over the hobbit’s face again. Suddenly it gave way to a look of relief and a laugh” (43). Here Tolkien gives a foreshadowing of what occurs in the climax of the book when Frodo stands at the Crack of Doom: “‘I have come,’ he said. ‘But I do not choose now to do what I came to do. I will not do this deed. The Ring is mine!’” (RK VI:3, 223). And just as Bilbo, when he surrenders the Ring, is restored to himself, so too Frodo, once the Ring is lost, is restored: “In his eyes there was peace now, neither strain of will, nor madness, nor any fear. His burden was taken away” (224).

In a letter written in 1963, Tolkien comments on the significance of Frodo’s failure, saying that “it became quite clear that Frodo, after all that had happened, would be incapable of voluntarily destroying the Ring.”9 Tolkien says that “Frodo indeed ‘failed’ as a hero,” but insists that this was not “a moral failure” because “Frodo had done what he could and spent himself completely (as an instrument of Providence) and had produced a situation in which the object of his quest could be achieved.”10 Frodo had begun this negative quest humbly: “I do really wish to destroy it. . . . Or, well, to have it destroyed. I am not made for perilous quests. I wish I had never seen the Ring! Why did it come to me? Why was I chosen?” (FR I:2, 70). Because of this humility “and his sufferings . . . [Frodo was] justly rewarded by the highest honour; and his exercise of patience and mercy towards Gollum gained him Mercy.”11 Not only do his comments to Sam as their terrible journey proceeds foreshadow his failure, they also reveal this humility and suffering:

“To do the job as you put it—what hope is there that we ever shall? And if we do, who knows what will come of that? If the One goes into the Fire, and we are at hand? I ask you, Sam, are we ever likely to need bread again? I think not. If we can nurse our limbs to bring us to Mount Doom, that is all we can do. More than I can, I begin to feel.” (TT IV:2, 231)

The Maker’s Pattern & Merciful Wisdom

In the 1963 letter, cited above, Tolkien adverts to two other themes: first, that behind all events there is a pattern and a Maker of that pattern. Fourteen years after Bilbo’s party and disappearance and nine years after his last visit, Gandalf reappears and tells Frodo the significance and history of the Ring. After characterizing Bilbo’s finding the Ring as “the strangest event in the history of the Ring so far,” Gandalf continues:

“There was more than one power at work, Frodo. The Ring was trying to get back to its master. . . . Behind that there was something else at work, beyond any design of the Ring-maker. I can put it no plainer than by saying that Bilbo was meant to find the Ring, and not by its maker. In which case you also were meant to have it. And that may be an encouraging thought.” (FR I:2, 65)

The second theme is that men are to be merciful to each other. Frodo’s mercy enables the destruction of the Ring to occur even at the moment when it looks as if the negative quest has failed. But before he undertakes his quest, Frodo does not feel mercy toward Gollum. When he hears the tale of his contest with Bilbo under the earth (The Hobbit 79–100), Frodo says to Gandalf, “What a pity that Bilbo did not stab that vile creature, when he had a chance? . . . He is as bad as an Orc, and just an enemy. He deserves death.” Gandalf’s reply is one of the richest thematic passages in the trilogy:

“Deserves it! I daresay he does. Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgement. For even the very wise cannot see all ends. I have not much hope that Gollum can be cured before he dies, but there is a chance of it. And he is bound up with the fate of the Ring. My heart tells me that he has some part to play yet, for good or ill, before the end; and when that comes the pity of Bilbo may rule the fate of many—yours not least.” (FR I:2, 68–69)

Free will, consequences, sin, virtue, hope, and the wisdom of the heart are the threads that constitute the thematic fabric of this passage. That Frodo has embraced Gandalf’s wisdom because of his suffering is apparent in the scene in which he finally meets Gollum face to face. Frodo rescues Sam from Gollum’s grasp by threatening to cut his throat, and Gollum begs for his life. After Frodo recalls Gandalf’s earlier words, he says to Sam, “I am afraid [of Gollum’s villainy]. And yet, as you see, I will not touch the creature. For now that I see him, I do pity him” (TT IV:1, 221–222). Later, this pity and a sense of comitatus cause Frodo to save Gollum from a just death at the hands of Faramir and his men, warrior-hunters. Frodo goes to the forbidden pool to fetch Gollum, who thinks he is alone and does not know that his being in this place is punishable by death:

Frodo shivered, listening with pity and disgust. He wished it would stop, and that he never need hear that voice again. . . . He could creep back and ask . . . the huntsmen to shoot. They would probably get close enough, while Gollum was gorging. . . . Only one true shot, and Frodo would be rid of the miserable voice for ever. But no, Gollum had a claim on him now. The servant has a claim on the master for service, even service in fear. . . . Frodo knew, too, somehow, quite clearly that Gandalf would not have wished it. (TT IV:6, 296)

Moreover, after bringing Gollum to Faramir, Frodo saves his life by taking him under his protection (TT IV:6, 300).

Places of Evil

In all of these events Tolkien carefully constructs the various figures in the book so that their actions are consistent with their moral character. This psychological verisimilitude adds to the sense of significance of the thousand-plus pages of the book.

Verisimilitude is also present in the kinds of languages that characters speak, their names, the places in which they live. Tolkien’s appendices at the end of The Return of the King, which deal with many subjects—including genealogy, etymology, and chronology—also contribute to the sense of reality. They contribute to the reality of the secondary world of Middle-earth by their prosaic quality. For example, in his appendix, “On Translation,” Tolkien says,

It seemed to me that to present all the names in their original forms would obscure an essential feature of the times as perceived by the Hobbits (whose point of view I was mainly concerned to preserve): the contrast between a wide-spread language, to them as ordinary and habitual as English is to us, and the living remains of far older and more revered tongues. (RK Appendix F, 412)

This passage is typical of the appendices in its scholarly scope, its assumed factualness, and its focus on a linguistic issue that a reader interested in a period would want to have analyzed. It is a veritable tour de force in its assumption that in this book is a secondary world that the sub-creator, the author, allows the reader to enter.

Verisimilitude in describing places has profound thematic significance in the book. The readers accept the reality of the geography and see how the places in the book are emblems of the morality of the beings who live within them. The ultimate sign of evil is Sauron’s Mordor:

Upon its outer marges . . . Mordor was a dying land, but it was not yet dead. And here things still grew, harsh, twisted, bitter, struggling for life. In the glens of the Morgai on the other side of the valley low scrubby trees lurked and clung, coarse grey grass-tussocks fought with the stones, and withered mosses crawled on them; and everywhere great writhing, tangled brambles sprawled. Some had long thorns, some hooked barbs that rent like knives. The sullen shrivelled leaves of a past year hung on them, grating and rattling in the sad air, but their maggot-ridden buds were only just opening. Flies, dun or grey, or black, marked like orcs with a red eye-shaped blotch, buzzed and stung; and above the briar-thickets clouds of hungry midges danced and reeled. (RK VI:2, 198)

Anti-life and hate-filled, Mordor embodies the nature of the being who has shaped it, Sauron, the Shadow, the Dark Lord, who himself is bodiless except for his “piercing Eye” (e.g., RK VI:3, 220). Mordor is the outward sign of the inward gracelessness of its ruler and his subjects.

A Land Without Shadow

Two places that are clearly beautiful and express the goodness of those who live within them are the Hobbits’ Shire and the Elves’ Lorien. The Shire is a place with rows of pleasant hobbit-holes, gardens, inviting lakes, flowing rivers, avenues of trees, fertile farms, clean air, good rain, ample sun, cleansing snow. However, in The Hobbit, the reader is aware that it is not Eden. Thus, the dreadful reign of Sharkey—Saruman—is made possible by Hobbits who cooperate with evil, thinking that they can control it.12 When the four Hobbits return from their adventures, they find it fouled. Frodo arrives at his former home, Bag End, to gardens full of weeds and built over, blocked light, “piles of refuse,” a “scarred” door, and a “bell that would not ring. . . . The place stank and was full of filth and disorder: It did not appear to have been used for some time” (RK VI:8, 297). Frodo calls this pollution in the Shire, “Mordor . . . just one of its works” (297).

After the evil forces are routed from the Shire, the Hobbits rebuild and replant. Sam carefully puts “saplings in all the places where specially beautiful or beloved trees had been destroyed, and he put a grain of the precious dust [that Galadriel had given him so many months before in the land of the Elves] in the soil at the root of each” (RK VI:9, 303). “Altogether [the year following] . . . was a marvelous year” (303).

This marvel is clearly connected with the elvish gift that Sam uses to benefit all in the Shire. For everything that is connected with the Elves is beautiful, and perhaps in no other creation of Tolkien’s imagination is his sacramental vision more apparent. Lothlorien, the home of Queen Galadriel, is fair: “Evil had been seen and heard there, sorrow had been known; the Elves feared and distrusted the world outside: wolves were howling on the wood’s borders: but on the land of Lorien no shadow lay” (FR II:6, 364). It is a place of trees, flowers, green hillsides, blue sky, afternoon sun, stars, fragrance, a place in which

Frodo stood awhile still lost in wonder. It seemed to him that he had stepped through a high window that looked on a vanished world. A light was upon it for which his language had no name. All that he saw was shapely, but the shapes seemed at once clear cut, as if they had been first conceived and drawn at the uncovering of his eyes, and ancient as if they had endured for ever. He saw no colour but those he knew, gold and white and blue and green, but they were fresh and poignant, as if he had at that moment first perceived them and made for them names new and wonderful. In winter here no heart could murmur for summer or for spring. No blemish or sickness or deformity could be seen in anything that grew upon the earth. On the land of Lorien there was no stain. (FR II:6, 365)

Foretaste of Redemption

In this place the desires described by Tolkien in his discourse on fairy stories come true. And yet, an elegiac tone moves through all things elvish. When the Ring is destroyed, if it is destroyed, they must leave Middle-earth, a grievous leaving. Galadriel tells Frodo:

“The love of the Elves for their land and their works is deeper than the deeps of the Sea, and their regret is undying and cannot be wholly assuaged. Yet they will cast all away rather than submit to Sauron.” (FR II:7, 380)

Explicit here is the painful condition of fallen man: Even when he creates a goodly place in this world that he loves, it will pass away. That it does in no way diminishes its importance or significance. Rather, at the end, the lesser yields to the greater. And at the end of the book, Tolkien has Frodo tearfully leave the restored Shire: “I have been too deeply hurt, Sam. I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me” (RK VI:9, 309). He leaves with Elrond and Galadriel,

. . . for the Third Age was over, and the Days of the Rings were passed, and an end was come of the story and song of those times. With them went many Elves of the High Kindred who would no longer stay in Middle-earth; . . . filled with a sadness that was yet blessed and without bitterness. (RK VI:9, 309)

After farewells to Sam and Merry and Pippin,

the ship went out into the High Sea and passed on into the West, until at last on a night of rain Frodo smelled a sweet fragrance on the air and heard the sound of singing that came over the water. . . . The grey rain-curtain turned all to silver glass and was rolled back, and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise. (RK VI:9, 310)

The natural and the homely, high gifts that Frodo so loved that he gave himself to save them, recall to man his roots in Eden even as they prefigure the ultimate gifts that Frodo experiences in his destination beyond Middle-earth. Tolkien embodies in his story a message of joy, of evangelium: That which is beautiful here is a foretaste, a sign, a sacramental of the ineffable that awaits those who serve. He achieves through his narrative what he contends at the conclusion of his essay “On Fairy-stories”:

All tales may come true; and yet, at the last, redeemed, they may be as like and as unlike the forms that we give them as Man, finally redeemed, will be like and unlike the fallen that we know. (Leaf 73)

Notes:

1. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Letters of . . . , ed. Humphrey Carpenter (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1981), 194. This is an excerpt from a draft of a reply to criticism of his work by Peter Hastings, the manager of the Newman Bookshop in Oxford dated September 1954 (187–188). Tolkien marked at the top of the draft “Not sent” and commented that “It seemed to be taking myself too importantly” (196).

2. J. R. R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1965), 47. All citations to the work in the text are from this source and will be indicated by “Tree” and the page number. The essay was originally composed as an Andrew Lang Lecture and was in a shorter form delivered in the University of Saint Andrews in 1938. It was eventually published, with a little enlargement, as one of the items in Essays presented to Charles Williams, Oxford University Press, 1947, now out of print. It is here reproduced with only a few minor alterations (Leaf vii–viii).

4. I am indebted to Father Stephen M. Fields, S.J., for his paper “Nature and Grace After the Baroque,” in which is his clear elucidation of Pope John Paul II’s assessment of the relationship between reason and faith, the natural and the supernatural. Presented at the biennial Jesuit Conference on the thought of John Paul II, Xavier University, Cincinnati, August 2000, it will be published by Fordham University Press, in a volume edited by John J. Conley, S.J., and Joseph W. Koterski, S.J.

5. John Paul II, Encyclical Letter Fides et Ratio: On the Relationship between Faith and Reason (Boston: Pauline Books and Media, 1998), chap. II, section 17, p. 30.

6. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring in The Lord of the Rings, 2nd edition (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1965), 10. All citations to the book are taken from this edition: The Fellowship of the Ring—FR; The Two Towers—TT; The Return of the King—RK; with Book: chapter, page numbers.

7. See, for example, RK VI:7, 295.

8. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1966), 9. First published September 21, 1937.

12. Frodo’s comments about Lotho as the Hobbits “scour” the Shire reveal his understanding of how people (Hobbits, in this case) can be corrupted by thinking they cannot lose power as they do evil (RK VI:8, 297).

This article is adapted from a longer paper presented at the 2001 conference of the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars, held in Omaha, Nebraska, in September 2001.

C. N. Sue Abromaitis is Professor of English at Loyola College in Baltimore, Maryland.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on J. R. R. Tolkien from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor