A Pilgrim’s View

James M. Kushiner on September 11 from Another Country

It was a strange experience to be away from America during the September 11 attacks. My wife told me several days later that I would be returning to a country different from the one that I had left for a pilgrimage of Orthodox Christians to the island of Iona in Scotland, on September 6.

When the news spread among us that America had been attacked, someone had to find a radio (we had no television). Slowly people returning from walking and praying around the island gathered in the common room to listen to BBC radio on the afternoon of September 11 (we were five hours ahead of New York). We listened in shocked silence. I could only think of the poor victims.

The only other American in our group of 30 was a Greek-American woman from New York City, whose family was spared. Among us there were Orthodox Christians from various ethnic backgrounds: Greek, Tibetan, Bulgarian, Flemish, Georgian, Cypriot, Irish, English, Welsh, and Scottish.

That evening, after a somber supper, we went to the chapel to pray the Orthodox service in remembrance of the dead, including all departed members of our families we wished to remember. Some wept.

The next day we ended our six-hour pilgrimage walk to various places on the island in St. Oran’s Chapel, the oldest intact building on the island (built about 1150). It stands in the middle of Reilig Oran—the graveyard of Oran, the sacred burial ground of the early kings of Scotland. There are also many recent graves around the chapel.

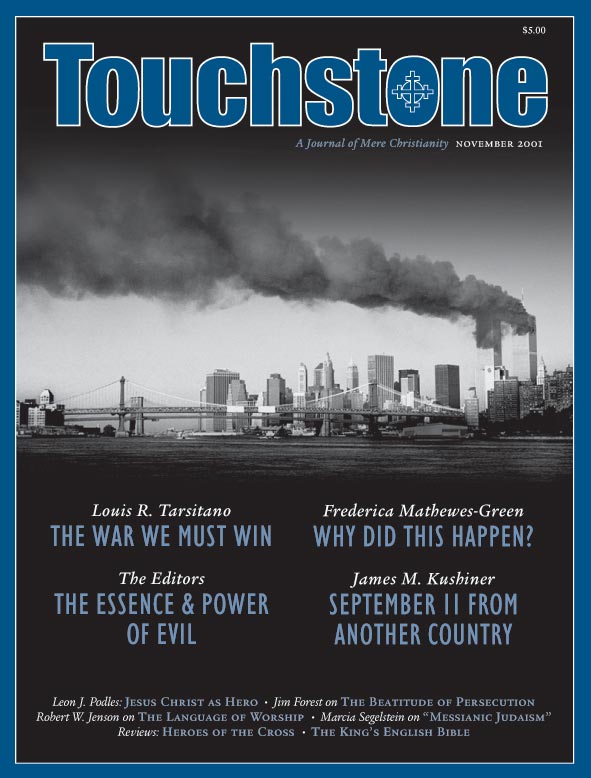

Afterwards I found several members of our group in the common room, soberly reading newspapers spread out on the floor and tables. The Times had many full-page color photos of the attack on America, which brought home to me the violence and scale of the attack. That evening we held another service of remembrance for the dead.

On Friday, after celebrating the Divine Liturgy for the Feast of the Holy Cross, we walked along the narrow road fronting most of the village’s houses down to the quay to catch the 9:00 a.m. ferry for the Island of Mull. Then, after an hour’s bus ride through some of the most stunning scenery imaginable, we caught another ferry to the mainland. At 11:00 a.m., the several hundred ferry passengers fell silent for three minutes in respect for the victims of September 11, silence that ended with the BBC broadcast of a tolling bell.

When we landed in Oban on the mainland, I lunched with a cousin and then took a train to Dumbarton, my mother’s birthplace. It’s a town originally founded on twin volcanic plugs that rise fortress-like at the confluence of the Clyde and the Leven. The next morning, I visited Dumbarton Castle, which is situated on both peaks. Indeed, they look impregnable.

Halfway up one of the walks, I stopped and stared for a long time at an artist’s rendering of these twin fortresses in 870, set ablaze and sacked after succumbing to a vicious siege by Vikings from Dublin. This fortress near the river and the sea was then known as Dun Breatann, “Fortress of the Britons.” I couldn’t help but think of the strong twin towers of the World Trade Center standing above the Hudson and the sea, symbols of economic power.

Warfare’s Place

Indeed, during the pilgrimage I was struck by how great a part warfare played in the lives of the saints in that part of the world—not unlike other places. There always have been those who seek to plunder and those who seek to terrorize. Sanctity did not save the monks from suffering and dying.

On Iona there is a beach, the White Strand of the Monks, on which 16 monks were slain by Vikings in 986. Farther south is the Martyrs Bay, near which Vikings put 68 monks to the sword in 806. And the people there had suffered much warfare and bloodshed in the centuries before the Vikings came, even during the period of St. Columba, who founded the first monastery on Iona in 563.

After walking in the cemetery, Reilig Oran, the day after the terrorist attacks, I came to have the feeling that death hangs heavy about the world, a feeling that stayed with me. After visiting the fortress of the Britons, I walked less than a mile to visit my 86-year-old great-aunt Helen. After greeting me, she handed me a parcel, saying, “We’ll be needing to go to the post office to mail this to Madame. This is heather for Donald’s grave.” Donald, her husband, had been killed in battle on June 26, 1944, in Caen, Normandy, just 20 days after D-Day.

After the war, many French volunteered to look after the graves of the slain from other countries. Since 1947, a French woman has been tending the grave in Normandy, and Helen has been sending her Scottish heather for the grave whenever it comes into bloom, usually in September. Holding the box in my hand, I felt I had been given a parcel of something more precious than gold to her. Donald had been a policeman in town when he was called up for service. Helen had a baby girl shortly after Donald was killed, the cousin that I visited in Oban, a girl who grew up without a father.

Helen had visited the grave many times as well, and was also able to find the grave of her father, Douglas, in Loos, France, just an hour’s drive northwest from Caen, near the border of Belgium. He had been killed there in 1915 during the First World War. Helen also never knew her father.

Later that afternoon I walked from Helen’s flat to Dumbarton Cemetery, to look for the graves of my great-grandparents, but to no avail. After more than an hour and a half of walking among the rows of high, upright monuments, many over six feet tall, I despaired of finding them. In the lengthening shadows of early evening, I studied the long, crowded rows of silent cut-rock pillars and slabs, some leaning precipitously. They looked like silent casualties of some plague, a war, or some evil spell, frozen like Lot’s wife in time and space—yes, the great enemy of man is death, and these are its victims, the “slain that lie in the grave” (Ps. 88:5). Like most of our ancestors, their names are eventually forgotten and the graves left untended. But they all are remembered by God, I thought.

The next day, Sunday, I took a morning train to Glasgow to meet Alan, a friend I had made in Iona, and we attended Divine Liturgy in a Greek Orthodox Church. After lunch we walked to Glasgow Cathedral, now a part of the Church of Scotland, but at one time the Catholic cathedral. Below the choir is the tomb of St. Kentigern (Mungo), who died some 250 years (612) before the Vikings sacked Dumbarton.

We were able to pray at his tomb, which somehow miraculously escaped the Reformers’ designs. While most graves are eventually forgotten, the tombs of many saints have been long remembered, perhaps as a testimony to the particularly strong evidence of that grace in their lives upon which the sure hope of our resurrection rests.

Our Enemy

I came away from Scotland with a heightened sense that our enemy is sin and death, and that those, like St. Columba and St. Mungo, who undertake the struggle against them engage a real enemy. The heroic struggles of the monks eventually brought Christianity to pagan lands, even though at times it looked as if their work and the work of previous generations would be undone by barbarian invasion and destruction.

I also came away with an extremely lively sense of the communion of the saints as we do battle with sin. Through the regular prayers of the hours, I was reminded of the deep mystery of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection on behalf of the fallen sinners that we are. The theme of struggle and willingness to die in the battle against enemies, seen and unseen, looms large, especially in this time of national crisis.

I was struck by a story Helen told me. Donald’s first and only son Douglas visited Normandy in 1994 for the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day. He was invited to speak as the son of one who had lost his life in Normandy in the battle to liberate Europe from the evil hand of Hitler. He spoke to several hundred people that day, many of them French locals, and afterwards received thunderous applause that went on and on.

Then, he said, every man, woman, and child waited to shake his hand. They wanted to touch the son of a hero who had laid down his life for their freedom. It was spontaneous, human, and natural. I suppose, in a sense, a similar desire led me to undertake this pilgrimage: to walk and see and touch the places where heroes of the faith labored on our behalf.

Of course, as one of the speakers on Iona said, going on pilgrimage doesn’t increase one’s chance of going to heaven. But it does provide one way to express the faith and grace within us that is trying to manifest itself in the world. And in expressing one’s faith in this way, in keeping “good company” with the saints, one may indeed strengthen it.

In going to a far country, I rediscovered the spiritual one that is my true home. In returning to a very changed country, I remembered that we all travel on to the same country. I saw more clearly that along the way to our true country and our true home, we must always be fighting against the sin and death we find at work in our own hearts.

Without this fight, our struggles against sin and death in the world will end like Dumbarton Castle, or the World Trade Center, and not like the monastery on Iona, whose faithful monks changed Britain even though so many died at the hands of sinners.

James M. Kushiner is the Director of Publications for The Fellowship of St. James and the former Executive Editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

11.5—September/October 1998

Speaking the Truths Only the Imagination May Grasp

An Essay on Myth & 'Real Life' by Stratford Caldecott

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor