Albanian Resurrection

The Story of Archbishop Anastasios & the Rebirth of the Albanian Orthodox Church

by Jim Forest

Europe’s jagged east-west divide happens to run through Albania, with the Catholic Church mainly in the north and the Orthodox Church in the south. Islam arrived under force of arms in the early sixteenth century, gradually becoming the principal religion of Albania. During the Ottoman period, the penalties for failing to convert were substantial. Perhaps 10 percent of the population today is Catholic, 20 to 30 percent Orthodox, and the rest at least nominally Muslim. (There is no religious census data. Albania’s Communist dictator, Enver Hoxha, when he met Stalin in 1947, estimated that 35 percent of the Albanian population was Orthodox.) During the Communist era atheism was the religion the State insisted on, and it still has many adherents.

When at last its infrastructure is developed, Albania could well become a major tourist center. A country a little larger than Vermont, there are more than 200 miles of shoreline and beaches on its Adriatic coastline. The inland terrain is so crowded with mountains and valleys that a Tibetan would feel at home. But for now few tourists dream of visiting. Albania is better known for its mafia than its resorts. The cars you see on the country’s pitted roads are in many cases stolen from owners in Western Europe. Electricity is likely to stop flowing at least for several hours a day—you never know when—and when the current is flowing, the surges pose a danger to anything that happens to be plugged in. Most factories are rusting ghost towns. A third of Albania’s three million people have been driven out by the wrecked condition of Albania’s economy to make their living in other countries. But the country’s greatest area of damage is to the soul.

Bishop for a Battered Church

When Archbishop Anastasios flew to Tirana, the capital of Albania, from Athens on July 11, 1991, he was arriving in what had recently been the world’s most militant atheist state. While every Communist regime had persecuted religion, only in Albania had all places of worship been closed and every act of private religious devotion banned. (Persecution began with the victory of Hoxha’s guerrilla forces in 1944; complete religious prohibition was ordered in 1967, when Albania was allied with China but wanted to outdo its protector in Marxist purity.) Sixteen hundred churches, monasteries, and other church-related buildings had been destroyed. Those few that had not been demolished had been turned into armories, post offices, barns, and laundries or put to other secular purposes.

Many thousands of Christians had been jailed or sent to labor camps, often dying as a consequence. The 440 clergy who had served the Orthodox Church 60 years earlier had been reduced to 22, all old and frail, some close to death.

While Archbishop Anastasios could recall occasionally citing Albania as providing one of the most extreme examples of religious persecution since the age of Diocletian, it had never crossed his mind that Albania might one day become his home and that he would become responsible for leading a church that most of the world regarded as not only oppressed but extinct, its only survivor being Albania’s most famous expatriate, Mother Teresa of Calcutta.

Born November 4, 1929, it was by no means certain Anastasios would become more than a nominal Christian, having grown up in a period when life seemed mainly shaped by secular ideologies, wars, and politics. When he was six, an army-backed dictatorship led by General Ioannis Metaxas was established in Greece. Metaxas liked the titles “First Peasant,” “First Worker,” and “National Father.” He led a Fascist regime, though one independently minded and non-racist, resisting alliances with its counterparts in Germany and Italy. From bases in Albania, Italy invaded Greece in 1940—Anastasios was ten. While Italian forces were quickly pushed back into Albania, in the following year the German army arrived in force. Greeks found themselves subject to a harsh tripartite German, Italian, and Bulgarian occupation, with civil war breaking out between factions of the resistance—the royalist right versus the Marxist left—even before occupation troops began to withdraw late in 1944. Anastasios was nearly 20 when civil conflict in Greece finally ended, the United States having weighed in on the side of democratic forces.

“I have many memories of the Second World War and the civil war in Greece that followed,” he told me as we drove over roads so damaged that they often resembled small models of the Grand Canyon. “This made me ask: Where is freedom and love? Many found their direction in the Communist movement, but I could not imagine that freedom and love could result from the Communist party or any other party. Very early in my life there was a longing for something authentic. During the war we had no school—we were more free. I read a lot, so many books! Not all of them helped my faith—Marx, Freud, Feuerbach. But there was a turning point. I can remember as if it were yesterday kneeling on the roof of our home, saying, ‘Do you exist or not? Is it true there is a God of love? Show your love. Give me a sign.’

“When you say such a prayer, the answer comes. It does not come with angels singing, but you realize God is there, in front of you and what he says: ‘I ask for you—not something from you.’ You understand in such a moment that what is important is not to give but to be given. That prayer was when I was a teenager—you can see why I have such a respect for teenagers. It can be a time when you ask the most important questions and are willing to hear the answer that is without words. Love and respect is shown to young people not in words but in the way you approach them, how you see them. It is the same with very old people in difficult times, people who are suffering.”

In his teens Anastasios studied at a gymnasium in Athens. “My main strength, it was discovered, was in mathematics, my main weakness in writing essays. My grades were high—I was at the top of my class. A certain path in life seemed obvious to everyone, but within myself there was a sense of being called toward the Church, not something everyone I knew sympathized with! At a critical moment, wrestling with the question of what is essential, I turned toward freedom and love. It was a turn toward Christ, in whom I saw the only answer.”

Finally he applied for the Theological Faculty of Athens University. “It was, of course, the age of technology. My decision to become a theology student was a scandal. What a waste! This is what many of my friends and teachers thought at the time.”

While studying theology, he found himself drawn into Orthodox youth activities, through which opportunities arose to meet young Orthodox Christians from other countries, an experience that made him realize that Christianity was far larger than Greece. The seeds of missionary thinking were planted. He began to wonder why it was that the Orthodox Church did so little to reach out to those who have no faith. “How had it happened that a church called to baptize the nations was so indifferent to the nations? St. Paul brought the gospel to Greeks. Who were we bringing it to?” It was a pivotal question that would shape the rest of his life.

From Army to Missions

After being drafted into the Greek army for a term, where he served as a communications officer, he returned to academic life, now going further with developing communication skills—homiletics and journalism. At the same time youth work continued, activity that always included religious education. He began training other catechists, finally designing textbooks for a three-year program of religious education for youth. More than a quarter-century and eight editions later, the books are still standard in all Greek Sunday schools.

In 1959 he founded a quarterly magazine, Porefthendes (Go Ye), devoted to the study of the history and theology of Orthodox mission. “With all my talk about mission, I was regarded at first as slightly insane, but gradually people began to understand that a Church is not apostolic if it is not carrying out mission. Apostolic means to be like the apostles, every one of whom was a missionary.” The journal lasted only a decade, but its existence occasioned the resurrection of the mission tradition in the Greek Orthodox Church.

In 1961, thanks to decisions made at the fifth assembly of Syndesmos, the Orthodox youth movement, a center also named Porefthendes was established in Athens with Anastasios as director. This in turn involved him in international ecumenical meetings on mission, events often organized by the World Council of Churches (WCC). Anastasios became a member of the WCC’s Working Committee on Mission Studies. He has since held a number of WCC leadership positions.

It was the desire to serve the church as a missionary that finally brought him to ordination as a priest. “When I was 33, at Christmastime, I went to the monastery on the island of Patmos. This is a period of the year when there are no tourists. You experience absolute silence and isolation. During this time I again considered returning to missionary activity. Then the question formed in my mind: What about the dangers you will face? Then came the response: Is God enough for you? If God is not enough, then in what God do you believe? If God is enough for you, go!”

Following his ordination he went to Uganda. “I thought finally my life had really begun. Africa, which I had thought about so often and with such longing, would be my home for the remainder of my life. So I hoped. But malaria ended that dream. It was the malaria of the Great Lakes, which can attack the brain. The first symptom was loss of balance. Then I had a fever of 104 degrees. It was my first experience of being close to death. I remember the phrase that formed in my thoughts when I thought I would die: ‘My Lord, you know that I tried to love you.’ Then I slept—and the next day I felt well! But this was only a providential remission. There was a second attack when I went to Geneva to attend a mission conference. Fortunately doctors there were able to identify the illness and knew how to treat it. But I had a complete breakdown of my health. When I was well enough to leave the hospital, they said I must forget about returning to Africa. This was a second death for me. It was only to serve in Africa that I had become a priest. Otherwise I would have taken a scholarly path. Friends said to me, ‘You don’t have to be a missionary—you can inspire others to be missionaries through your teaching.’ But it had always been clear to me that what you say you must also do—how could I teach what I wasn’t living? Only I had no choice. I had to return to the university.”

By 1972 he had been elected by the Faculty of Theology of Athens University as assistant professor of the history of religion. The same year, in recognition of the importance of his academic work with its special emphasis on mission, he was ordained a bishop. Four years later he was full professor, teaching courses on African religion and other living faiths, being the first at the university to introduce Islam as an area of study.

The Albanian Call

His eventual recovery from malaria made it possible in 1981 to return to East Africa, arriving when the Orthodox Church in Kenya was in a state of division and severe crisis. His work extended to Uganda and Tanzania as well. After nearly a decade in Africa, he could begin to imagine eventually returning to the University of Athens and devoting himself to teaching and writing. Instead there was something altogether unimagined that intervened in his life: neither Africa nor Athens but Albania.

In January 1991, one month after the government in Tirana had allowed the formation of non-Communist political parties, Archbishop Anastasios received a telephone call from the ecumenical patriarch in Istanbul asking if he would be willing to go to Albania as exarch to see what, if anything, was left of the Orthodox Church. It was at the time intended not as a permanent assignment, only a reconnaissance effort to see if and how the local church could be revived. It would require, however, a substantial interruption of his work in Africa. After a night of prayer he said yes, though it would take six months before the reluctant authorities in Tirana finally issued a visa.

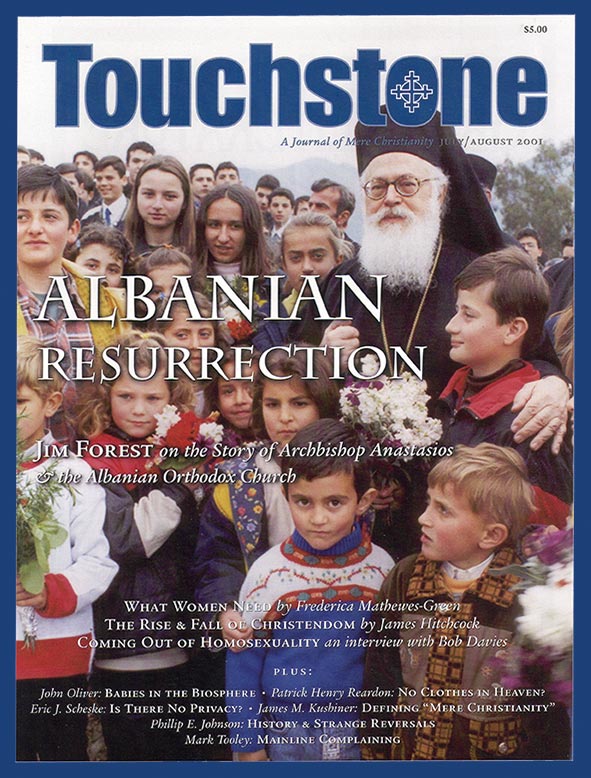

One of those at the airport to greet the archbishop was Tefta Kuge, a woman of thick graying hair, hands that mirror her every sentence, and a radiant smile. She recalls: “When the archbishop came, we went to meet him at the airport in a bus, 30 or 40 people. I was invited even though I had on only an old dress and slippers—I had been cleaning the church! I had never seen an airplane before, not close. An airplane! I kept saying to the others, ‘Look!’ I was amazed. Then he came out and I exclaimed, ‘He is like a butterfly!’ It was a very hot day but the wind was blowing his robes. Imagine, a bishop in our country! I felt as if Christ himself had come to Albania!” A reporter asked her if she were happy. “Yes,” she told him. “The church is alive again. It’s my church and it’s alive!” It struck her as a sign from God that the name Anastasios means Resurrection.

Archbishop Anastasios’s first action on arrival was to visit Tirana’s temporary cathedral, though still in a devastated condition with a large hole in the roof. The old cathedral on the city’s main square had been demolished years before to make way for a hotel. The one church in Tirana that was beginning to serve as a place of public worship had been a gymnasium since 1967. Though the Easter season was past, on his arrival Archbishop Anastasios gave everyone present the Paschal greeting, “Christ is risen!”, lit a candle, and embraced local believers. “Everyone was weeping,” he remembers, “and I was not an exception.”

One often hears people in Albania, even non-Christians, refer to Archbishop Anastasios as a saint. After traveling with him far and wide in Albania, I can only say “Amen” to that opinion. I have rarely in my life met anyone who possesses such a contagious faith.

Service of Love

He was 61 when he arrived in Albania. He has proved to be not only an inspiring man of faith but also a talented administrator who has been able effectively to direct a complex process of church renewal. In the past decade, 80 churches have been newly built, nearly 70 restored from a ruined condition, 5 monasteries brought back into existence, 135 other church buildings restored, and a number of schools founded. Since the seminary was opened in the port city of Durres in 1992 (now near Durres on its own rural hilltop), there have been 120 ordinations. There is a church radio station and newspaper, an icon painting and restoration studio, a candle factory, and a printing house. No one knows how many thousands of baptisms there have been since 1991, only that conversion is a frequent event.

Much of his work, however, is hard to quantify. He explained: “Here our Orthodox people have many ethnic backgrounds—Greek, Slav, Macedonian, Montenegran, Romanian. It used to be there was great division within the Orthodox Church. Our first goal was to create unity among Orthodox Christians. After so much persecution, we can no longer allow division. I recall in Korca saying, ‘Do you think the forest is more beautiful if there is only one kind of tree?’ The forest we are growing is made up of truth, beauty, and freedom.”

The church has set up clinics in major population centers, including one in Tirana that offers treatment of a Western European quality, with all medication provided gratis to anyone in need, no matter what his faith. Eleven kindergartens have been opened. There are summer camps and many youth programs.

While his official title is Archbishop of Tirana and All Albania, he has occasionally been called the Archbishop of Tirana and All Atheists. “For us each person is a brother or sister,” he explains. “We don’t have enemies. If others want to see us as enemies, it is their choice, but we have no enemies. We refuse to punish those who punished us. The oil of religion should be used to soothe and heal the wounds of others, not to ignite the fires of hatred.” He also has been determined that the church would help not only the baptized but anyone in need. “Always remember that at the Last Judgment,” he says time and again, “we are judged for loving him, or failing to love him, in the least person.”

In 1997, when Albania was plunged into civil anarchy, the church provided emergency aid to 25,000 families. In 1999, when half-a-million refugees fled to Albania from Kosovo, the church took care of 50,000 people and still runs the last refugee camp in the country.

There are programs to assist the disabled, a women’s rural health and development program, an agriculture and development program, work with prisoners and the homeless, free cafeterias, and emergency assistance to the destitute. (Most of this work is carried out through the Diaconia Agapes—Service of Love, a church department set up in 1992.)

Welcome Amid Threats

Without hesitation or a cooling of the heart, the archbishop welcomes each person who wants to speak to him. When we visited the Ardenica Monastery, one of the few religious centers to survive the Hoxha period with little damage (it had become a tourist hotel complete with prostitutes), Archbishop Anastasios was approached by a shy man who said, “I am not baptized—I am a Muslim—but will you bless me?” The man not only received an ardent blessing but also was reminded by the archbishop that he was a bearer of the image of God.

A few days before, he had met with national leaders of the Moslem community, which he called “part of the normal rhythm” of his life. “During my long journey I have learned one must always respect the other and regard no one as an enemy. At first it was a surprise to the Moslem leaders, but I always visit them on holidays and other occasions. We must help each other for the sake of our communities. Tolerance is not enough—there must be respect and cooperation. If we turn our backs on each other, only atheism benefits. We also have to meet with respect those who have no belief.”

There are similar visits with Catholic bishops, clergy, and lay people. He helped welcome Mother Teresa when, in her old age, she was able to visit post-Communist Albania, and is pleased that one of the main streets in Tirana has been renamed in her honor—and a postage stamp graced with her portrait. (I happened to meet one of the Missionary Sisters of Charity at the Orthodox Church’s Annunciation Clinic in Tirana. The city’s Orthodox and Catholic cathedrals are nearly side by side.)

Though a monk who has never known married life, Archbishop Anastasios has a remarkable ease with children. When we happened to pass a mobile dental clinic on the way to the Monastery of Ardenica, the archbishop decided not only to greet the local children waiting in line outside the van but also to test the dental chair himself, much to the delight of the children watching. He was immediately a beloved uncle.

The fact that Archbishop Anastasios is Greek has been a problem. Apart from the Greek-speaking minority, many Albanians regard Greeks with suspicion. “If you are a Greek,” he explained to me, “you must be a spy. How else could an Albanian whose mind was shaped in the Hoxha period think—a mind entirely formed by an atheistic culture? You learn to see each person entirely in socio-economic terms. You cannot imagine that a man in his sixties is coming here because of love! Therefore we cannot complain about such people. It is not their fault. We pray in the Liturgy both ‘for those who hate us and those who love us.’ It is an algebraic logic in which numbers exist below zero. But how to respond to hatred? Here you learn that often the best dialogue is in silence—it is love without arguments.”

He has often been the target of severe criticism and false reports in the Albanian press. Efforts have repeatedly been made to get rid of him. A law was almost passed that would have forced any non-Albanian bishop to leave the country. His life has been repeatedly threatened. It is one of many Albanian miracles that he is still alive and well. In his office, he showed me a bullet that had lodged itself in double-paned glass. But on the window ledge near the bullet, he pointed out a gray pigeon tending a single egg in a flowerpot. “A bullet and an egg!” he commented. “Perfect symbols of Albania at the crossroad.”

The bullet was one of several fired at his office in 1997. It was in this period that he issued an appeal that had as its theme, “No to arms, no to violence.” Against the advice of many friends, he refused to leave the country. “I am the captain of the ship,” he explained. “Others may leave but for me that is not an option.”

Unsleeping Christians

While inevitably the archbishop is Albania’s most prominent Christian, what he has helped achieve since his arrival would have been impossible had it not been for those people who, at huge personal risk, kept the church alive in secret during the time of persecution.

One such person is the secretary of the church’s Synod, Father Jani Trebicka. In the years when every religious symbol and gesture was prohibited and he had a factory job, he secretly made hundreds of small crosses that he would leave in the night at ruined churches as a gift for those who came to pray in secret. He was one of the first persons ordained a priest after Anastasios came to Albania. As a child growing up in what he called “the age of propaganda,” his family kept religious feasts in a hidden way. He told me the story of a woman whose hidden icons were discovered and confiscated. When the police were leaving, she said to them, “You forgot one icon.” They replied, “Give it to us.” She then made the sign of the cross on her body. “There it is and no one can take it away.”

Another of the country’s onetime secret Christians is today the bishop of Korca, Metropolitan Joani. His father had been jailed before he was born as an enemy of the State. “Many times they nearly arrested me,” he told me. “I know so many people who went to prison. Once the secret police were going to raid my office—someone told them I had a Bible—but the director of my clinic was able to stop them. He had sympathy for me, and because he was a cousin of the director of the secret police, he could protect me.” A theologian and scholar who was trained at Holy Cross School of Theology in Brookline, Massachusetts, he limits the time he spends writing and translating theological texts because he regards projects to serve the poor as more important. “At the Last Judgment I will not be congratulated for my theological writings. I will be asked why I didn’t help a certain old woman.” He took me to lunch at the “service of love” free restaurant his diocese had opened across the street from his office.

One of Albania’s bravest Christians during the Communist era was Marika Cico, also living in Korca. Now 95 and nearly blind, she is a fountain of joy, welcoming a stranger like myself as if he were her son. She and her sister Demetra (who died two years ago) arranged many baptisms, weddings, and Liturgies in their home. Services were in the dead of night behind blanket-draped windows in a back room of their house. Working with the Cico sisters was a community that included a secret priest, the late Father Kosmas Qirjo, and a number of friends, among them the young man who is today Metropolitan Joani. Members of the group repeatedly engaged in “unsleeping prayer”—40-day periods of continuous prayer, each person praying in one- or two-hour shifts, for the end of persecution.

“Our priest, Father Kosmas, was very poor. His black raisa [clerical robe] was so faded it was almost white. He had seven children and lived in a muddy hut with one window. When we talked with him, we realized he was an apostle. He had not been well educated, but he read the Bible by the light of the moon, and God enlightened him. Like other priests, he became a laborer but never gave up being a priest. ‘I am a priest,’ he said, ‘and I will serve the church even if the church has no buildings.’

“He lived far away. We would send him a message, ‘Please find wool so Frangji can make clothing for the children,’ our way of asking for Communion. On Thursday we would make candles and bread for the Eucharist. Then on Friday night Fr. Kosmas would arrive, and that night we could receive Communion! He came to Korca five or six times every year. For 23 years, from 1967 to 1990, this is how we lived. There was not one church open in all of Albania.”

Risen Indeed!

In 1990, when it was finally possible to engage in public worship without being arrested, the group organized a service for the feast of the Theophany, commemorating the baptism of Jesus. Marika showed me a brass mortar and pestle they used as a bell so that they could draw attention to their procession through the city. Thousands came out of their houses to take part.

I met a woman with a similar spirit in a village near the border with Greece. She told me about how her family had managed to live a hidden religious life at a time when even a red-dyed Easter egg could bring the police to the door. Had her mother not been regarded as crazy, she would have been arrested. “I am crazy like my mother,” the woman told me.

The word most often used to describe the church in Albania is resurrection—ngjallja in Albanian. The church’s seminary is dedicated to the Resurrection. The church newspaper is called Resurrection. Many churches have been given the same name. In my last visit with Archbishop Anastasios before flying back to Holland, he gave me a newly painted Resurrection icon, in which we see Christ standing on the destroyed gates of hell while pulling Adam and Eve from their tombs. Adam and Eve represent the entire human race, in which each woman is a daughter of Eve, each man a son of Adam, and all linked to each other in Christ. The icon also mirrors the experience of the church in Albania.

On the back of the archbishop’s pendant is the Cross, surrounded by two shafts of wheat. The symbol represents the Gospel text, “Unless the grain of wheat falls into the ground and dies, it cannot bring forth new life.” Archbishop Anastasios often remarks, “The Resurrection is not behind the Cross but in the Cross.”

Jim Forest is secretary of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship and author of Praying with Icons and The Ladder of the Beatitudes. He is writing a book about the resurrection of the Orthodox Church in Albania for the publications department of the World Council of Churches. Another work in progress is about confession. He lives in Alkmaar, Holland. More of his photos of Albania are posted at: www.incommunion.org/resources/albania.asp.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor