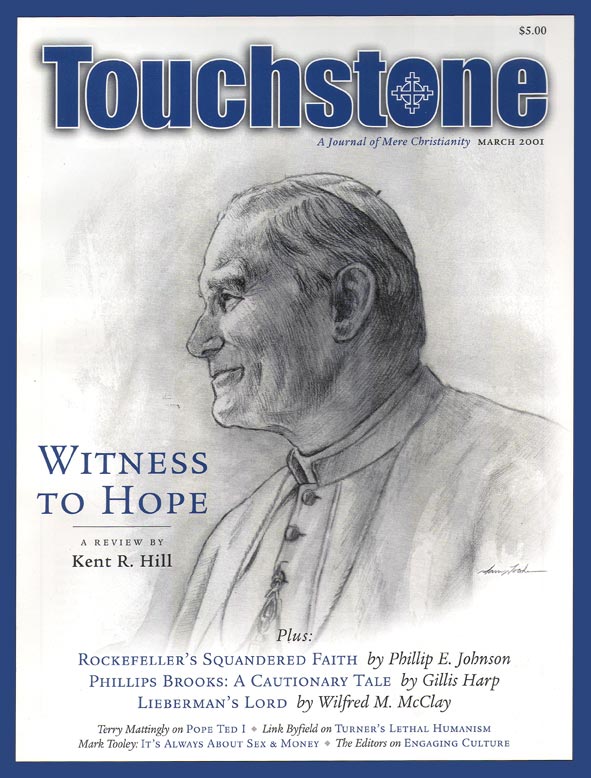

A Pope for Our Times

Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul II

by George Weigel

New York: HarperCollins, 1999

(992 pages; $35.00, cloth)

reviewed by Kent R. Hill

“It is when night envelops us that we must think of the breaking dawn, that we must believe that the Church is reborn each morning through her saints.”

—Pope John Paul II, Rheims, 1996 1

Who is John Paul II? The images are so starkly different.

The buoyant, open pope with his broad smile, at his prime, on the front of George Weigel’s Witness to Hope, and the painfully bent and shuffling papal image drifting across our TV screens in recent months. There is, after all, a presumption among many that wrinkles and a reactionary disposition go together.

How could the same pope in September 2000 canonize both the forward-looking Pope John XXIII, the architect of the “progressive” Vatican II, and the “anti-modernist” Pope Pius IX? How could a pope with lifelong Jewish friends and an impressive record of helping reconcile the church with the Jewish people canonize a pope about whom questions have been raised regarding his attitudes towards the Jewish people? How do we accurately understand the present pope? Never mind that both popes had a reputation for deep piety and that the process of canonization for Pius IX began over a century ago.

No pope has done so much to break down the walls that divide Christians or been so effective in engaging non-Christians in modern times, and yet in August 2000, so the national pundits tell us, a document was issued by the Vatican that allegedly moves the Catholic Church away from the openness of Vatican II and towards an intolerant and narrow view of all others.

A lengthy review of Dominus Iesus (Lord Jesus)2 in The Boston Globe charged that the John Paul II-approved Declaration shifts the Roman Catholic Church back in the direction of “pre-Vatican II triumphalism.”3 The reviewer pontificates that the new document reflects a “fortress mentality,” promotes “religious imperialism,” and devalues Judaism.

In fact, The Globe readers had been exposed to a gross caricature of the document in question. Similar misrepresentations of the document appeared in print and voice media throughout the country, and they reflect a profound ignorance or outright prejudice regarding the matters under discussion.

A Definitive Biography

In light of this, it is all the more important for us to discern clearly the man behind the headlines, and the importance of Pope John Paul II for our times. This requires careful scholarship, fairness and balance, and an open mind. Fortunately, that is precisely what the reader will find in George Weigel’s definitive biography of John Paul II, Witness to Hope—a nearly 1,000-page book that by the fall of 2000 had already sold in hardback more than 300,000 copies worldwide, including 120,000 in English.

Weigel’s biography is the product of an extraordinary labor of careful and meticulous research. The work is rich in detail, yet wonderfully succinct in its summaries and analyses of key events and ideas. Though the book reads well as a unit, its chapter organization and index allow it to serve as a superb reference work for looking up precise events and topics.

The author is himself an accomplished thinker, well versed in theology, philosophy, human rights advocacy, and foreign policy. He possesses the ideal background to place in context the life and achievements of Pope John Paul II. Indeed, that is why it was John Paul II himself who in late 1995 invited Weigel to write the biography, with two guarantees given up front. First, Weigel could count on generous access to the pope and the Vatican for his research and, second, this would not be an “authorized” biography. The pope would not review the final product. The work was to be entirely the author’s.

Weigel does not feel constrained to praise every position, appointment, or policy of the pope, but the book is all the better for this, and the central message of John Paul II and his ideas is in no way diminished by such honesty. Indeed, quite clearly, John Paul II would have been satisfied with no less on the part of his biographer.

The Young Priest & Bishop

Karol Wojtyla (pronounced Voy-TEE-wah) was profoundly shaped by his background. Born in Poland in 1920, at age nine he was compelled to deal with the death of his mother. His father was a military man and deeply religious. Late at night and early in the morning, the young boy often found his father on his knees in prayer.

The beneficiary of a fine classical education, Wojtyla was particularly fond of theater and literature. His intellectual prowess was evident at an early age, and he was valedictorian of his high-school class in 1938. His university years were interwoven with the tragedy of World War II—and the particular anguish for the Polish of first being invaded by the Nazis and then by the Soviets. The assault by the Nazis and Soviets on Polish culture and the Catholic Church was the cauldron in which Wojtyla’s faith was formed and tested. He learned to pray doing forced labor in limestone pits. Wojtyla’s particular sensitivity to the plight of the Jewish people can be dated to childhood friendships and his personal encounter with the horrors of the Nazi persecution of the Jewish people.

His courage was early demonstrated in his active participation in the underground efforts to sustain Polish culture and provide leadership in Catholic youth activities. Beyond accepting the danger connected with these commitments, Wojtyla eventually sensed a divine call to the priesthood, which among other things, provided a more tangible way “to live in resistance to the degradation of human dignity by brutal ideology” (69). By 1942, Wojtyla was immersed in an underground seminary in preparation for his vocation as a priest. The stakes were high. Some of his classmates were executed by the Gestapo for attending the illegal seminary.

The portrait of Wojtyla that emerges from the 1940s and 1950s reveals a young priest who was deeply pious, humane, and approachable, a wonderful listener, a lover of nature and sports, and genuinely interested in other people. He modeled for other priests the importance of interacting with lay people on their own turf, rather than just within the confines of the church walls. He loved to hike, kayak, and ski with his friends and youth groups. It was around the campfires at night that lay people, often struggling with the conflict between the historic beliefs of the Christian faith and the hostile and secular milieu of their educational or vocational environment, encountered the living, vibrant Christian faith of a friend, who also happened to be a priest.

At the age of 38, in 1958, Wojtyla became the youngest bishop in Poland. Five years later he became an archbishop. It was his active participation in Vatican II (1962–1965), however, that turned a little-known Polish bishop into one of the better-known leaders in the Catholic Church worldwide. Pope John XXIII, who convened Vatican II, intended for the council to begin the process of the church more effectively engaging the world in dialogue. Wojtyla fully supported the agenda, believing that the church needed clearly to distinguish Christian humanism from other kinds of humanism, and in so doing provide an antidote to the despair that was the natural byproduct of inadequate contemporary views of the human person.

Weigel asserts that Wojtyla’s most important contribution to Vatican II was in the debate and preparation of Gaudium et Spes (Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World). Indeed, the arguments Wojtyla made in discussions and preparation for this document foreshadow clearly the dominating themes of his own pontificate, which would begin a decade and a half later. Wojtyla warned that the council should avoid “lamentations on the . . . miserable state of the world” and instead reflect a commitment to dialogue with the world. The church should make its proposal to modernity through “the power of arguments,” not through “moralization and exhortation” (167). Weigel considers the “philosophical and moral linchpin” of the entire council to be Gaudium et Spes 24: “Man can fully discover his true self only in a sincere giving of himself” (169).

A Slavic Pope with a Message

In 1967, at the exceptionally young age of 47, Karol Wojtyla was named cardinal. Eleven years later, he would stun the world by becoming the first Slav ever elected pope, and the first non-Italian pope in 455 years.

In the prime of his life, vigorous, with a clear sense of mission and purpose, John Paul II left little doubt from the first moment of his pontificate what his message to the world would be. It was completely consistent with the message of his life and writings to date, and fully in harmony with the winsome, open spirit of Vatican II.

On October 22, 1978, at his installation, John Paul II quoted the most repeated command in all Scripture: “Be not afraid.”4 Like a Bach fugue, John Paul kept returning to the same refrain:

Be not afraid to welcome Christ and accept his power. Help the Pope and all those who wish to serve Christ and with Christ’s power to serve the human person and the whole of mankind.

Be not afraid. Open wide the doors for Christ. To his saving power open the boundaries of states, economic and political systems, the vast fields of culture, civilization, and development.

Be not afraid. Christ knows “what is in man.” He alone knows it (262).

Consistent with John 3:16–17, the theme would be hope, not condemnation. To be sure, there were consequences for not aligning oneself with transcendent realities, our true humanity, and the Creator of the universe, but those consequences were already manifest in the despair and lostness of the world. The point was to share the “good news” that there is a way out of the sad, desolate, and even cruel cul-de-sacs of modernity.

Everything that John Paul has done or said in his pontificate has been and is in some way a development or amplification of this theme of hope. After his election as pope, and just two days before his coronation, John Paul informed the diplomatic press corps that the Holy See had no desire for power as the world understands the term. Rather, the Holy See would seek to contribute “above all to the formation of consciences,” and he went on to remind the press corps of a conviction and assertion that would be central to his pontificate—religious freedom is the most important test of any truly just society (268).

John Paul II must be considered not just the primary Catholic leader of the era, but one of the preeminent moral voices of modern times as well. He has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to address in a compelling manner people of all nations and faiths. Consider his speech before the United Nations General Assembly on October 5, 1995—the speech in which he told the assembly that he came to them as a “witness to hope” (776), the origin of Weigel’s title for his biography. He forcefully stated:

We must learn not to be afraid, we must rediscover a spirit of hope and a spirit of trust. Hope is not empty optimism springing from a naïve confidence that the future will necessarily be better than the past. Hope and trust are the premise of responsible activity and are nurtured in the inner sanctuary of conscience where “man is alone with God” and thus perceives that he is not alone amid the enigmas of existence, for he is surrounded by the love of the Creator! (14)

It is such clearheaded, forthright analysis and unapologetic witness to a spiritual antidote for the poison that threatens to debilitate and destroy modern civilization that makes John Paul II the most persuasive moral voice of our time.

A Psychological Earthquake

John Paul has been uniquely positioned by experience and prudential conviction to walk the fine line between inappropriate mixing of church and politics and the appropriate use of the moral and religious authority of the church to speak on behalf of religious freedom, human rights, and justice. Nowhere in the twentieth century was the impact of one religious leader on the course of current events so profound as that of Pope John Paul II on the demise of communism in Eastern Europe.

To note the importance of the church and John Paul II in the unraveling of communism is not at all to say that Western military, economic, and technological might, and the bankruptcy (moral and economic) of Marxism were not pivotal factors; they were. But the way in which communism collapsed and the recovery of conscience and will that helped speed that process were clearly influenced by the moral authority and witness of the church under John Paul II.

The election in 1978 of John Paul II was the worst possible nightmare for the Kremlin and for the Communist leaders of Poland. Indeed, secret Polish Communist party memos of March 1979 identify their native son, now pope, as “our enemy” (304).

On June 2, 1979, the first day of his pilgrimage to Poland, Pope John Paul II was greeted by 3 million Poles in Warsaw—twice the normal size of the city’s population. In Victory Square, John Paul II gave what Weigel considers perhaps “the greatest sermon of his life.”

The pilgrimage ended in Krakow on June 10, 1979, with the largest crowd in Poland’s history hearing John Paul II proclaim:

You must be strong, dear brothers and sisters. . . . You must be strong with the strength of faith. . . . Today more than in any other age you need this strength. You must be strong with the strength of hope, hope that brings the perfect joy of life. . . . When we are strong with the Spirit of God, we are also strong with faith in man. . . . There is therefore no need to fear. . . . So . . . I beg you: never lose your trust, do not be defeated, do not be discouraged. . . . I beg you: have trust, and . . . always seek spiritual power from Him from whom countless generations of our fathers and mothers have found it. Never detach yourselves from Him (319).

Stalin reportedly jested in scorn years before: “How many divisions does the pope have?” Well, the truth is that there are forces more powerful than might of arms, and Poland had just experienced this reality. So what really happened?

One political scientist described what had occurred as a “psychological earthquake.” In Weigel’s words, “people felt and acted out the change before they could articulate what had happened to them. Without thinking much about it, they began behaving differently” (321). Adam Michnik noted that the pope seemed to have a remarkable ability to appeal to the consciences of all—believer and nonbeliever alike.

The rise of Solidarity is inconceivable, according to Weigel, apart from this first papal pilgrimage to Poland. “A new sense of self-worth, a new experience of personal dignity, and a determination not to be intimidated any longer by ‘the power’ were by-products of the papal pilgrimage, for nonbelievers as well as believers” (324). And what was unleashed was change unaccompanied by violence. Remarkable indeed.

In January 1990, John Paul II noted that often the “point of departure” for the peaceful revolution had been a church. Step by step, “candles were lit, forming . . . a pathway of light, as if to say to those who for many years claimed to limit human horizons to this earth that one cannot live in chains indefinitely. . . .” In the end, people had “overcome their fear” (610).

John Paul II went on to insist that the urgent task following the implosion of Marxist states was to enshrine human rights in the rule of law, and this requires “respect for transcendent and permanent values.” To make man “the measure of all things,” according to the pontiff, is to make him “a slave to his own finiteness.” The rule of law must be built with “reference to him from whom all things come and to whom this world returns” (610). This is vintage John Paul II, for what he proposes for post-Communist regimes is precisely what he insists is necessary to save Western societies from continuing to sink into the morass and quicksand of relativism and rootless, self-destructive individual autonomy.

A Bold Theologian

One of Weigel’s boldest assertions flies in the face of a fairly common dismissal by some within the church, and certainly in the secular intelligentsia, that John Paul II is really just a conservative throwback to an earlier age. On the contrary, the pope’s rich experience as a priest very familiar with the problems of contemporary, often quite secular, lay people, and his profound critical and creative theological thinking about how Christian truths interact with the challenges of human relationships, produced in him a commitment and capacity to help the church speak more effectively on these issues than it had often done before.

In September 1979, John Paul II began a series of 130 fifteen-minute addresses on the “theology of the body.” It took four years to complete and has been published in English in book form.5 Weigel considers this to be “one of the boldest reconfigurations of Catholic theology in centuries” (336) and “a kind of theological time bomb set to go off, with dramatic consequences, sometime in the third millennium of the Church” (343). He believes that The Theology of the Body “may prove to be the decisive moment in exorcising the Manichaean demon and its deprecation of human sexuality from Catholic moral theology” (342).

The basis for our humanity, according to John Paul II, is, in Weigel’s paraphrase, a “yearning for a radical giving of self and receiving of another”(337). Sin is a corruption of self-giving, and lust is the opposite of true attraction in that it centers on transitory pleasure gained through the use or abuse of another. Genuine attraction would seek the other’s good through the gift of self. In his 1960 book Love and Responsibility, the future pope asserted that sexual attraction was good because it brought men and women together in marriage—a difficult but helpful experience in which we learn “in patience, in dedication, and also in suffering what life is, and how the fundamental law of life, that is, self-giving, concretely shapes itself” (142).

One of the most important legacies John Paul II will leave when his life and pontificate come to an end will be a series of encyclicals that are deeply thoughtful and insightful, and often of great interest and importance for non-Catholics. An example of such an encyclical is his tenth—Veritatis Splendour (The Splendor of Truth), released in October 1995. Weigel considers this to be “one of the major intellectual and cultural events” of John Paul II’s pontificate (686). The American Lutheran scholar Gilbert Meilaender argues that he is “hard pressed to imagine an equally serious statement on the nature of theological ethics issuing at this time from any major Protestant body” (693). Indeed, most of Veritatis Splendour is completely consistent with the finest Protestant thought on ethics; the service rendered by John Paul II to the rest of the Church here is precisely in his ability to capture so well what C. S. Lewis called “mere Christianity,” and what G. K. Chesterton described as “orthodoxy.” This is Christian moral analysis at its best, and it was intended to deal with the shallow moral reasoning so dominant in our day.

Nowhere in Veritatis Splendour is John Paul II more incisive than in his discussion of what is wrong with modern notions of freedom. Weigel’s summary here is helpful.

The widespread notion that freedom can be lived without reference to binding moral truths is another unique characteristic of contemporary life. . . . [I]t had been widely understood that freedom and truth had a lot to do with each other. No more. And the uncoupling of freedom from truth, led in one, grim direction. Freedom, detached from truth, becomes license, and license becomes freedom’s undoing. . . . Freedom untethered from truth is its own mortal enemy (688).

Just as John Paul II powerfully defended the countless victims (both born and unborn) sacrificed or debased on the altar of parental (married or unmarried) self-love and misuse of sexuality, he eloquently defended the notion of fundamental human rights before the nations of the world. He connected the dignity of humanity with the recognition and cultivation of the dimension of the spirit. Pope John Paul II considers his speech in French to UNESCO on June 2, 1980, as one of his most important. In that speech, he asserted that a decline in confidence in humanity’s prospects was robbing life of the “affirmation and joy” essential to nurture human creativity. The solution, he insisted, could only be found in the realm of the spirit, the true core of culture (377).

Whether one agrees with John Paul II or not, one cannot deny that the most important religious tradition in the formation of the West is being articulated here with intelligence and passion. At the very least, the cultural and political debate has been enriched.

The Wings of Faith & Reason

Perhaps no word more aptly describes John Paul’s personality and religious convictions than “balanced.” Indeed, this, along with a sense of humor (a lifelong trait ever evident in his smile), is one of the surest signs of his spiritual health and “orthodoxy.” The difference between “orthodoxy” and “heresy,” as G. K. Chesterton has pointed out so well, is that the latter takes one part of the truth and makes it the whole truth. The orthodox position affirms both the humanity and divinity of Christ, both faith and reason, and both grace and an appropriate response in deeds.

This commitment to balance is complemented further by an “orthodox” and scripturally based prioritization of elements essential to the Christian faith. Jesus’ insistence on the importance of “love” and the appropriate inner dispositions towards each other, rather than simply “right” actions or “rational” affirmations, was early nurtured in Wojtyla by his experience with the Polish church during times of trial.

A quarter of a century before he became pope, as a professor of philosophical ethics, Wojtyla eloquently argued for what he called the “Law of the Gift.” In the words of George Weigel,

This “Law of the Gift” was built into the human condition. . . . Responsible self-giving, not self-assertion, was the road to human fulfillment. Wojtyla posed it not only as an ethic for Christians, but as a universal moral demand arising from the dynamics of the human person, who is truly a person only in relationship (136–137).

John Paul II has been an eloquent advocate in our times of the proposition that there must be a proper balance between reason, revelation, and mystery. He refuses to accept the proposition that one must choose between faith and reason.

In October 1998, John Paul II released his thirteenth encyclical, Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason). It had been almost a century and a quarter since the last papal statement on the topic. With his excellent educational background and knowledge of philosophy, the present pope was well suited for the task. The encyclical scolds contemporary philosophy for often refusing to deal with the big questions. By ruling out a consideration of transcendence, what John Paul II calls the “horizon of the ultimate,” philosophy will inevitably sink into the dark, windowless night of solipsism (841–842).

John Paul II powerfully criticizes any who would divorce thinking from believing, and he presses his point by quoting Augustine.

Believing is nothing other than to think with assent. . . . Believers are also thinkers: in believing, they think and in thinking, they believe. . . . If faith does not think it is nothing (841).

According to the pope, “Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth” (842). John Paul II is fully in the tradition of Aquinas with his encyclical and also in harmony with Newman when the latter exclaims:

It will not satisfy me, what satisfies so many, to have two independent systems, intellectual and religious, going at once side by side, by a sort of division of labour, and only accidentally brought together. It will not satisfy me, if religion is here, and science there, and young men converse with science all day, and lodge with religion in the evening. . . . I want the intellectual layman to be religious, and the devout ecclesiastic to be intellectual.6

Beyond the Borders

In his eighth encyclical, Redemptoris Mission (The Mission of the Redeemer), released in December 1990, John Paul II summarizes for the church the right attitude towards the world in bearing witness to Christian truth: “The Church proposes; she imposes nothing. She respects individuals and cultures, and she honors the sanctuary of conscience” (636).

Four years later, John Paul II surprised the world by communicating with it in an absolutely unprecedented way for a pope—through a very engaging, personal, and open response to written questions posed by an Italian journalist. Crossing the Threshold of Hope became an international bestseller. He shared his own personal journey of faith and his hopes for the world, and the book attracted far more than the Catholic faithful.

Massimo D’Alema, General Secretary of the Democratic Party of the Left in Italy (and formerly a bright star of Italian communism), was very impressed by the pope’s analysis of the collapse of communism and his assertion that the future society would have to be constructed on the basis of “a quest for values . . . a spirituality” (805). D’Alema asserted that John Paul II had “an influence greater than the Church” because he could advance universal values in a way that “moves beyond the borders of the Catholic Church” (805). In October 1998, D’Alema became Prime Minister of Italy.

In preparation for the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000, John Paul II convened the College of Cardinals on June 13, 1994. One of the initiatives he had proposed to the cardinals earlier in the year was that the church ought to examine its conscience in order “to acknowledge the errors committed by its members, and in a certain sense, in the name of the Church” (741).

In fact, John Paul II had already been engaged in this sort of confession and restitution in the name of the church for some time. Weigel notes:

On forty previous occasions, John Paul had directly or indirectly acknowledged the errors of Catholics throughout history: errors in interreligious relations, errors in the Church’s relationship to its own reformers, errors in the Church’s treatment of indigenous peoples, errors in its treatment of women, errors that had contributed to the East-West break of 1054 and to the intrawestern fracture of the sixteenth-century Reformation (741).

Some in the church were very nervous about John Paul II’s policies here, and yet, as Weigel summarizes the pope’s position, “cleansing the Church’s historical conscience was essential if the Gospel were to be preached credibly” (742).

John Paul II will not let the modern church get off the hook by claiming that the problems of today are simply caused by moral relativism and the secularized modern world. The church must, he insists, accept its share of responsibility for the late twentieth-century religious crisis “by not having shown the face of God” (745).

Reconciliation & Dialogue

This spirit of repentance and honesty helped set the stage for the progress John Paul II was deeply committed to advancing in three areas: Christian unity, reconciliation between Jews and Christians, and dialogue between religion and science.

No theme is more emphasized in John Paul II’s pontificate than the necessity of working towards reconciliation between Christians. In November 1980, in a visit to Cologne, he said he was coming as a pilgrim “to the spiritual heritage of Martin Luther,” and he confessed that “we have all sinned” in breaking the mutual bonds of Christian unity (364). Three years later, on the 500th anniversary of Luther’s birth, John Paul II wrote a letter on October 31 to Johannes Cardinal Willebrands, President of the Secretariat for Christian Unity, in which he called for scholarship, “without preconceived ideas,” to work towards healing the divisions between Roman Catholicism and Lutheranism. Fault, wherever it lies, must be acknowledged (472). In an ecumenical prayer service held in 1985, John Paul II declared that “divisions among Christians are contrary to the plan of God” (504).

By the end of the century, multiple years of work resulted in the Vatican and the Lutheran World Federation acknowledging that whatever the differences may have been in the sixteenth century, in our times there is basic agreement on the meaning of “justification by faith.”

There can be no question that the spirit of Vatican II in the 1960s and the pontificate of John Paul II have played major roles in the improved relations between the Catholic Church and other Christian churches, particularly Evangelical Protestants. In 1995, John Paul II released the encyclical Ut Unum Sint (That They May Be One), which Weigel calls “the boldest papal offer to Orthodoxy and Protestantism since the divisions of 1054 and the sixteenth century” (761). A major personal disappointment for John Paul II, however, has been the failure to make more progress in terms of reconciliation with the Orthodox Church.

In 1986, John Paul II became the first bishop of Rome to enter the synagogue of Rome in over 1900 years—a symbolic act of goodwill not missed by the Jewish community. In his address in the synagogue John Paul II noted that Vatican II had made it clear that the Jews as a people could not be collectively held responsible for what had happened to Jesus, that there was no theological justification for discrimination against Jews, and that anti-Semitism “by anyone” was condemned, and then he added, “I repeat, ‘by anyone.’” He noted that Jews were irrevocably called by God, and further stated: “With Judaism . . . we have a relationship which we do not have with any other religion. You are our dearly beloved brothers and, in a certain way, it could be said that you are our elder brothers” (484–485). Major progress was made in subsequent years towards normalizing relations between Israel and the Holy See.

Long before John Paul II became pope he had demonstrated through conviction and practice that science and Christianity ought not to be considered irreconcilable enemies. Both before and after he became pope he arranged for and participated in dialogues between Christian leaders and scientists. “All truth is God’s truth,” is fundamental to John Paul II’s theology and intellectual beliefs.

John Paul II commissioned and then accepted the final report of a major church commission to investigate the church’s seventeenth-century condemnation of the teachings of Galileo. The report asserted that it was a mistake for the church to have concluded that Catholic tradition was undermined by Galileo’s acceptance of the Copernican revolution. And so, 350 years after the death of Galileo, one graduate of Krakow’s Jagiellonian University helped exonerate an earlier graduate of the same university.

But John Paul II did not just accept the commission’s findings on the seventeenth-century error of the church, he reminded science that science often relied on far more than just empirical data, and thus scientists needed philosophers just as philosophers needed scientists. Once again, John Paul II’s fundamental commitment to “balance” was in clear view.

Gifted & Down to Earth

The accomplishments and spirit of the pontificate of Pope John Paul II are truly extraordinary. His erudition is remarkable, which makes his down-to-earth qualities and spirit even more praiseworthy. John Paul II is a gifted linguist who rarely needs an interpreter, a classically trained scholar and philosopher, and a playwright and poet, who yet is sympathetic with and accessible to the common person—to the lay person, the person struggling with the joys and trials of family life, the person who enjoys sports and delights in nature.

In the late 1960s or early 1970s, after he had become a cardinal, Wojtyla was skiing near the Czechoslovak border when he was stopped by a border patrol. His identification papers were demanded of him. When the militiaman read that the papers belonged to a cardinal, he immediately launched a verbal assault. “You moron, do you realize whose identity papers you’ve stolen? This is going to put you away for a long time.” When Wojtyla protested his innocence, the militiaman shot back, “A skiing cardinal? Do you think I’m crazy?”

In so many ways, the skiing cardinal is a metaphor for precisely how Wojtyla intended the church to challenge the world’s stereotypes of the church. “An intelligent Christian, a joyful Christian, a listening Christian, a winsome Christian? Do you think I’m crazy?” Indeed, and whoever heard of a bishop or cardinal who wrote poetry and plays? But Wojtyla did. They were just alternative ways of getting the message out.

As pope, his record is outstanding indeed. By October 1998, the twentieth anniversary of his pontificate, he had already produced thirteen significant encyclicals, two new codes of canon law, a new Catechism of the Catholic Church (the first in 400 years), and conducted thousands of audiences. He had appointed 159 new cardinals, and 101 of the 115 members of the College of Cardinals eligible to vote were appointed by him. Of 4,200 bishops, he had selected 2,650. The final tally will be even more dramatic. He has served longer and with more influence than any other pope in the twentieth century.

Pope John Paul II has turned the orientation of the papacy outward—from bureaucracy to evangelism. He has emphasized Christian discipleship and holiness. He has taken the Christian message, in a winsome and compelling way, to the most visible world stages. He has particularly captivated the youth throughout the world in his World Youth Days, surprising and chagrining the pundits who felt so sure that his “conservative” message would not gain a hearing there. (Evidently, the young respond to heartfelt convictions and calls for self-sacrifice and integrity.) And he has played a pivotal role in what Weigel has called the “revolution of conscience” in Eastern Europe and beyond (607). Weigel concludes that it is “plausible to argue that the pontificate of John Paul II has been the most consequential since the sixteenth-century Reformation” (849).

Everything about this pope has been and is turned outward—towards service, towards communication, towards persuasion, towards manifesting love. But it is an outward orientation nurtured by roots that reach deep into the heart of God—roots watered by a daily discipline of solitude (even in the midst of a crowd), and a daily self-dedication and conviction that in the end he is “playing to an audience of One.”

A Living Witness

The chief virtue of Witness to Hope is that Weigel gets out of the way and simply lets the essence and warmth of John Paul’s spirit shine forth. And what saves it from hagiography is that he does not let John Paul II the man overshadow his message to the Church and the world—a message of hope and salvation firmly and perfectly embodied in Jesus Christ.

It is the spirit of Christ and his message of salvation that breaks forth through the life and winsome smile of this gentle but powerful Christian leader. We are fascinated by someone who simultaneously affects the historical moment profoundly and does so primarily by pointing human beings to that which is beyond the historical moment, to the Creator and his eternal truths.

Indeed, to do this amid the confusion and descent into relativism so typical of modernity, it takes more than solid theology and brilliant apologetics, important and valuable as these gifts of the Spirit and human creativity might be. It certainly takes more than a restructuring of the church, better organizational techniques, and enhanced political acumen, useful as these surely can be.

It takes “embodiments” of the Truth in flesh and blood to point the way. It has ever been such with human beings. That is why the Incarnation was indispensable to our coming to understand divine truths. We needed to see God “in the flesh” to glimpse what love, sacrifice, and meaning are all about. It is still the same with us. When people come to faith, it is often connected with encountering the grace and forgiveness of God made manifest, even if ever so slightly, in the pale reflection of Christ in one of his servants.

But if one of his servants does not just dimly reflect the love and spirit of God, but does so with bright radiance, consistency, power, intellect, poetry, and passion, then a potent force is unleashed that God can powerfully use to bring hope and salvation to floundering humanity. Pope John Paul II has been and is such a man—a man of God and a man for our times.

Thus John Paul II by his life calmly and firmly advances the proposition that “this world” is not all there is, that death is not the end, and that transcendent truth and morality are real, however imperfectly they may be grasped by us. He serves the present moment, reflects it, but is ultimately not bound by it.

John Paul II is a living, breathing rebuke to the relativism and solipsism of our age, and he offers the keys of Scripture and the Church to help us escape the narrow, confining prison of modernity. It is this which draws us to him—the window in him to that which is beyond him, to that which is both inviting and eternal.

John Paul II is “the man for our times” precisely because he points so well to that One who is beyond time—the One who is the Alpha and Omega, the author and finisher of our Faith.

Notes:

1. Quoted in George Weigel, Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul II (New York: HarperCollins, 1999), p. 795.

2. The 36-page “Dominus Iesus”: On the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church, was authored by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

3. Paul Wilkes, “Only Catholics Need Apply,” The Boston Globe, September 10, 2000.

4. According to N. T. Wright in Following Jesus, this phrase appears 365 times in Scripture. Quoted in Philip Yancey, Reaching for the Invisible God (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2000), p. 81.

5. The Theology of the Body According to John Paul II: Human Love in the Divine Plan (Boston: Daughters of St. Paul, 1997).

6. Newman, The Idea of the University (South Bend, Indiana: Notre Dame University Press, 1982), p. xxxviii.

Kent R. Hill has been President of Eastern Nazarene College in Quincy, Massachusetts, since 1992. A scholar of Russian studies, he has lived for extended periods in Russia and is the author of The Soviet Union on the Brink: An Inside Look at Christianity and Glasnost.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor