The Domestic Workplace

Feminism, Careers & the Family: Who Has Gained? Who Has Lost?

by Allan Carlson

The modern history of “women’s liberation” can be read as a tale of increasing human bondage and female submission to the corporate state.

By “corporate state,” I mean the union of the giants—big business and big government—who, whatever their surface disagreements, share a deep and lasting interest in the weakening of family bonds and the disappearance of the autonomous home.

Before expanding on my argument, I want to add two caveats: First, I am not very concerned, here, with the attitudes and fate of the wealthiest 5 to 10 percent of the population, now or in the past. The rich and powerful—women as well as men—have always enjoyed special choices or dispensations that have set them apart. I want to focus instead on the attitudes and lives of the 90 to 95 percent: those fated by birth or circumstance to labor in order to survive. In other words, I am less concerned about people in careers such as physician or lawyer or stockbroker and more concerned about folk in “careers” such as cafeteria worker, janitor, or assembly line.

Also, I am not here to defend the so-called “traditional family” or “Ozzie and Harriet family” of the 1950s. There were architects of this family model, one that I have described elsewhere1 as “a household engineer bonded to an organization man in a companionate marriage focused on informed consumption in the suburbs.” While I am fascinated by the rise and fall of this historical episode, I would emphasize the inherent weaknesses of this family system, which left it as a “one-generation wonder” incapable of transmitting its set of values to subsequent generations.

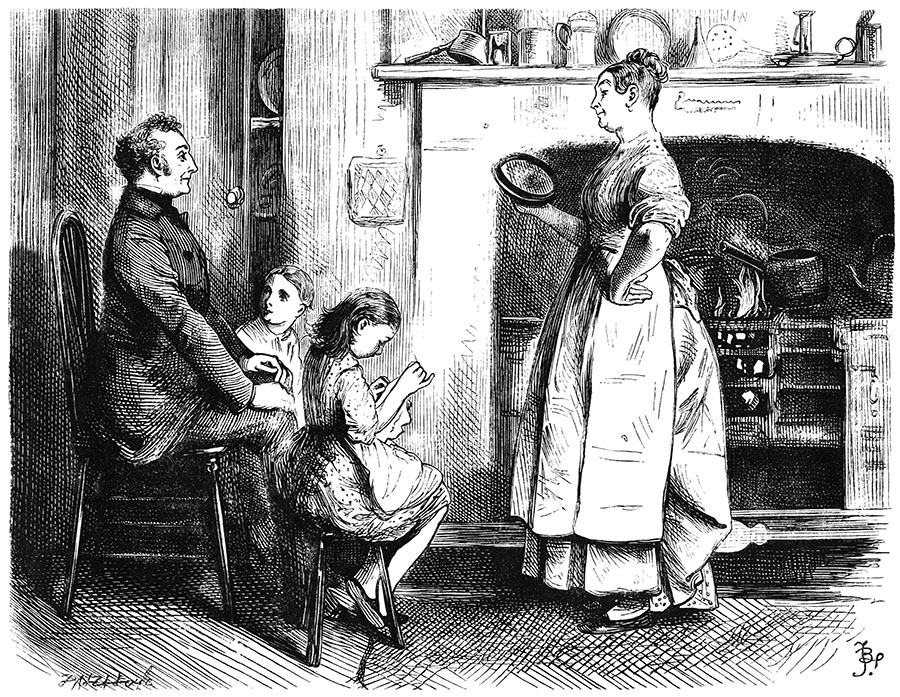

Work & Home Before Industrialization

Indeed, to understand our current situation we must search much deeper in the past. And there we find a basic revolution in human social affairs, one that started about two hundred years ago, as the process of industrialization began its work. This kind of organization rested on the use of power machinery, expanded markets, a highly refined division of labor, and strict worker discipline. Most important for our purposes, it also involved an altogether new and radical separation of “work” from “home.” Until about 1800, for all of human history, the vast majority of people had lived and worked in the same place; that is, their dwelling place was also their work place. The peasant or family farm or the craftsman’s shop or the fisher’s cottage was the normal pattern of human life for many thousands of years.

If we can shed our modern biases for a moment, we might even appreciate some aspects of the lives lived in these ways. Marriage brought a union of the sexual and the economic, in a manner that brought gain to both partners. Their homes were rich in daily event, places where husband, wife, and children all shared in the work of the family enterprise. Children were economic assets in these productive homes, each one welcomed warmly into the family circle. The household was the center of education in basic and advanced skills. Estimates suggest that, in this household-centered milieu, at least 60 percent of all goods were created and produced by the women. In such context, women found deep and real satisfaction: as the guardians of function-rich, economically productive homes, their fertility and their creativity combined in ego-fulfilling ways.

Even in our own century, we can see surviving pockets of this old order, focused on domestic production. In her brilliant study entitled The Transformation of Rural Life, Southern Illinois, 1890–1990, anthropologist Jane Adams describes life for the vast body of agrarian American women, circa 1900:

Work aimed at earning a cash income and work that provided daily needs were not sharply distinguished, just as child care was not a discrete body of activities. Similarly, work that was appropriate to men and to women was, in many cases, not strongly distinguished.

Professor Adams continues:

While urban middle-class women became consumers in the new industrial era, farm women [stayed as] petty commodity producers. By the turn of the century virtually all farm women who had land to do so raised poultry for meat and eggs and sold dairy products as whole cream, butter, and cottage cheese. They oversaw their children’s work caring for and milking the cows and churning the cream, and they controlled the income from these products. Farm women of all classes also produced a wide variety of other products: dried apples, cornshucks for tamales, flowers, and duck and goose down.2

These folks lived and worked in a rich network of relationships, of neighbor and kin. As Professor Adams explains: “These relationships, inscribed in the landscape . . . only as ephemeral footpaths linking home to home, also appear in recollections of daily life—relationships of reciprocity, of formal swap work, and charitable sharing.”

The Kentucky poet, essayist, and novelist Wendell Berry describes in literary fashion the same sense of completeness known to the people of that old order. As he writes in his short story, “A Jonquil for Mary Penn,” a tale set in the 1930s:

[O]n the rises of ground or tucked into folds were the gray, paintless buildings of the farmsteads, connected to one another by lanes and paths. Now she thought of herself as belonging there, not just because of her marriage to Elton, but also because of the economy that the two of them had made around themselves and with their neighbors. . . . She had learned to think of herself as living and working at the center of a wonderful provisioning: the kitchen and garden, hog pen and smokehouse, henhouse and cellar of her own household; the little commerce of giving and taking that spoked out along the paths connecting her household to the others.3

From Home to Factory

But the mode of life Berry describes came to an end wherever and whenever the industrial process spread. The new factories wrenched both women and men out of their homes for reorganization into centralized, more efficient productive units, where family relationships were, at best, an inconvenience. Wives now competed against husbands, and children against parents, in the sale of their labor, which tended to drive wages down. The goods produced by factories using a refined division of labor rapidly displaced household-produced commodities such as clothing, shoes, furniture, and eventually food. Meanwhile, government—or the state—industrialized other family functions, starting with primary education in 1840s, and extending later to child protection, old age security, primary health care, and eventually even early child care.

The emergence of the labor movement in the mid-nineteenth century, though, marked an effort by workers to restore some semblance of autonomy to their households, through pursuit of what came to be called a “family wage.” The goal was not creation of a “separate sphere” in the home so much as defense of a “private sphere,” where some measure of family self-sufficiency could undergird a sense of independence: where the household could survive as an autonomous force. As the Philadelphia Trade Union explained to its members in the mid-nineteenth century:

Oppose [employment of the womenfolk] with all your mind and with all your strength for it will prove our ruin. We must strive to obtain sufficient remuneration for our labor to keep the wives and daughters and sisters of our people at home. . . . that cormorant capital will have every man, woman and child to toil; but let us exert our families to oppose its designs.4

In the early twentieth century, the legendary labor leader Mother Jones continued the family wage campaign. Although a fairly leftish magazine bears her name, Mother Jones actually comes up short on what now passes for progressivism. As historian Bonnie Stepenoff shows in a recent issue of Labor History, Mother Jones “believed women had an important role to play as nurturers and motivators of unionmen, but not as workers.” The issue for Jones was “not the injustice of paying such low wages to silk workers, but the injustice of employing [wives and mothers] in the mills [at all]. The solution became, not a better deal for the female workers, but a better deal for the fathers, who, in Jones’s view, should support them.”5

But the “industrial principle”—which poet John Crowe Ransom once described as a force “of almost miraculous cunning but no intelligence”6—defied such labor goals. It subverted family wage arrangements and continued to spread, into process after process.

Feminism & the New Bondage

What has been the role of ideological feminism in this change? Simply this: while providing a rationale for liberation from productive homes and meaningful family bonds, it has also encouraged new forms of bondage and submission.

As two historians have put it: “The real historical role of feminism . . . was to deliver women by the millions as factory hands, subject to factory discipline and severe limitation of movement and action.”7 Indeed, early in the twentieth century, the feminist movement actually crafted an informal alliance with the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), America’s leading advocate for the full industrialization of human life. In 1903, the NAM passed a feminist-inspired resolution arguing that “no limitation should be placed upon the opportunities of any person to learn any trade to which he or she may be adapted.”8 The NAM fiercely opposed the family wage as a compensation principle, denouncing Mother Jones as a social radical for her defense of the autonomous home. The NAM and the feminist movement fought together against special work rules designed to protect women laborers. There is also some evidence that the National Association of Manufacturers covertly funded the National Women’s Party during the 1920s.9 This was the group that would draft the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution.

In all this, we might see modern feminism as the ideological architect of a conditional surrender by families to industrialism. Stripped of sentimentality and rhetoric, the terms of the surrender looked like this: family households agreed to give up their remaining spheres of independence; industrial organization via corporation or state would be allowed to absorb the last remaining family functions; and in exchange, women gained free access to abortion and subsidized child care.

If one accepts certain assumptions, there is a logic to this deal. And some of the more clear-headed feminist analysts are quite blunt about their embrace of dependence on the corporate state. Carole Pateman, for example, argues that women’s dependence on the corporate state is preferable to dependence on individual men, since women do not have to “live with the state” or sleep with the corporation as they must with the male creature.10 Frances Fox Piven is equally frank in her stated preference for what she calls public patriarchy over private patriarchy; the former, she argues, offers a better venue for the exercise of female power.11

So where does this leave us? It is true that one reasonable stance toward the future is simply to accept things as they are, and ready oneself for submission to the new order of the corporate state. Serfs in the medieval age knew some joy, and contemporary serfdom offers a considerably better standard of living, even an SUV for those who behave.

Is there even an alternative? Would I, for example, advocate a return to the regime of the family wage?

I would not, for even at its best, the family wage ideal succeeded only in keeping a weakened family system alive, with the father largely absent, with the mother under special stress, and with the home relatively fragile.

Another Way Home

But there is another choice. It recognizes that the essential modern problem remains the radical separation of “work” and “home.” Marriage and family life thrive when the two are unified; they suffer when “work” and “home” are apart. Any real basis for marriage and family autonomy must focus on healing this breach. Wendell Berry makes the point with characteristic bluntness in his essay, The Unsettling of America: “If we do not live where we work, and when we work, we are wasting our lives and our work too.”12

So this “Third Way” becomes a process of creative social engineering, but not to reconfigure the family to conform to the demands of the corporations, the new form of feudalism often promoted in contemporary “work-family” conferences. Rather, we need to manage and control social and economic changes to accommodate and protect the natural family. Borrowing words again from Mr. Berry, “we are going to have to gather up the fragments of knowledge and responsibilities” that have been turned over to governments, corporations, and specialists, “and put those fragments back together again in our own minds and in our families and households and neighborhoods.”13

In part, this means pulling certain functions back into the home: functions critical to the maintenance of marriage and the rearing of children. Some couples may start with home births, reconnecting this most important of actions to the family household. Others may start with breast feeding, understanding this means of infant feeding as a primal form of home production, one intended by nature to be human rather than corporate in nature. Some may start, and many will continue, with conscious home education. Now past its “pioneer phase,” home schooling involves nearly two million American children, and it is important not just for its educational effects on children, impressive as those are. The evidence also shows that the creation of a home school strengthens the family and strengthens the marriage by focusing the whole family circle on the children and on the task of learning.14 Home gardens and other forms of family-centered productive self-sufficiency may follow as well, as steps toward refunctionalizing the home.

Also in part, this task of reconnecting work and family will involve men and women deliberately reintegrating market labor into their homes. A family business may be the solution for some; a home office for others; telecommuting for another group; and the creative development of new kinds of jobs, using new communication and information technologies, involving work at home for still more. All such developments should tend to strengthen the economic foundations of family living, and the autonomy of households.

There may be less glamour, and probably less recorded income, under this “Third Way.” But I hope you can see that it also offers the possibility of strengthened family and community bonds, and renewed appreciation for the foundations of true liberty.

Notes:

1. Allan Carlson, From Cottage to Work Station: The Family’s Search for Social Harmony in the Industrial Age (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1993).

2. Jane Adams, The Transformation of Rural Life: Southern Illinois, 1890–1990 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994) pp. 88–89.

3. “A Jonquil for Mary Penn,” in Wendell Berry, Fidelity: Five Stories (New York: Pantheon Books, 1992), p. 74.

4. Quoted in R. Milkman, “Organizing the Sexual Division of Labor: Historical Perspectives on ‘Women’s Work’ and the American Labor Movement,” Socialist Review 49 (January/February 1980), p. 198.

5. Bonnie Stepenoff, “Keeping It in the Family: Mother Jones and the Pennsylvania Silk Strike of 1900–1901,” Labor History 38 (Fall 1997), pp. 432–449.

6. John Crowe Ransom, “Reconstructed But Unregenerate,” in I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition (Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1977 [1930]), pp. 15–16.

7. Ferdinand Lundberg and Marynia Farnham, Modern Woman: The Lost Sex (New York: Harper Brothers, 1948).

8. See A. G. Taylor, “Labor Policies of the National Association of Manufacturers,” University of Illinois Studies in the Social Sciences 15 (1927), pp. 35–37, 126–139.

9. See L. H. Mohr, Frances Perkins (Croton-on-Hudson, New York: North River Press, 1979), p. 192; and Mary Anderson and M. N. Winslow, Women at Work: The Autobiography of Mary Anderson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1951), p. 171.

10. Carol Pateman, “The Patriarchal Welfare State,” in A. Gutmann, editor, Democracy in the Welfare State (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1988), pp. 231–260.

11. Frances Fox Piven, “Ideology and the State: Women, Power and the Welfare State,” in L. Gordon, editor, Women, the State and Welfare (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), p. 255.

12. Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture (New York: Avon, 1977), p. 79.

13. Wendell Berry, A Continuous Harmony: Essays Cultural and Agricultural (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972; 1970), p. 79.

14. See Allan Carlson, “Will the Separation of School and State Strengthen Families? Some Evidence from Fertility Patterns,” Home School Researcher 12 (1996), p. 4.

This paper was originally presented as a lecture for the Joseph C. Woodford Forum on Critical Social and Political Issues at Colgate University, Hamilton, New York, on December 1, 1999.

Allan C. Carlson is the John Howard Distinguished Senior Fellow at the International Organization for the Family. His most recent book is Family Cycles: Strength, Decline & Renewal in American Domestic Life, 1630-2000 (Transaction, 2016). He and his wife have four grown children and nine grandchildren. A "cradle Lutheran," he worships in a congregation of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. He is a senior editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on family from the online archives

more from the online archives

24.6—Nov/Dec 2011

Liberty, Conscience & Autonomy

How the Culture War of the Roaring Twenties Set the Stage for Today’s Catholic & Evangelical Alliance by Barry Hankins

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor