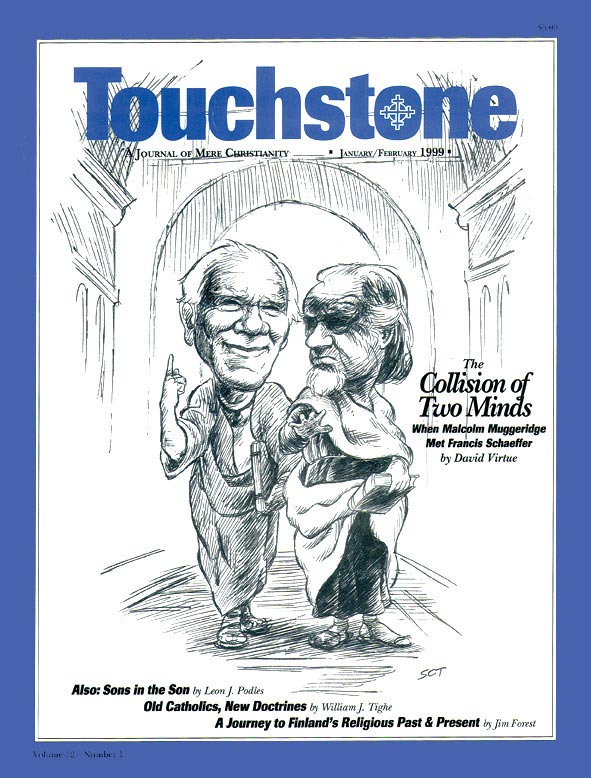

The Collision of Two Minds

Malcolm Muggeridge Meets Francis Schaeffer

by David Virtue

While I was studying in London in the sixties, the name of Francis Schaeffer, an American Christian apologist and evangelist living in Switzerland, lit up the evangelical sky. He had written a book with the seemingly self-evident title, The God Who Is There. The book, however, directly exposed and challenged the intellectual presuppositions and cultural climate of the second half of the twentieth century.

In it Schaeffer articulated what he devised and called the “line of despair” (Europe about 1890 and the United States about 1935) in philosophy, art, music, and the general culture, as well as the New Theology. He attempted to show that for modern man, absolutes had died, modernity reigned, and the floodwaters of secular thought had overwhelmed the Church because its leaders did not understand the importance of combating a false set of presuppositions. Young people were being raised on the old sense of what was right and wrong based on absolutes the West had established from a biblical worldview, but on leaving home they were being exposed to “rationalism” and “humanism” that saw man as the center of all things and pushed God to the sidelines or out of the picture altogether.

Schaeffer feared that the generation following his might not understand what was consciously or unconsciously shaping their thinking, that their faith would suffer as a result, and that they would fall if they were not made aware of the changes in the culture and the intellectual climate that was pushing for change.

To many of us, as students of theology and philosophy who were being affected by the cultural changes, Schaeffer was a breath of fresh air in the otherwise stagnant currents of contemporary evangelicalism.

While the list of evangelists emerging on the American and British scene steadily grew (Billy Graham had by now established himself as the evangelist primus inter pares), there was no one like Schaeffer, who insisted that presuppositions must first be examined by those creating the culture, then addressed and hopefully demolished before the gospel could be articulated, taken seriously, and believed. Schaeffer was afraid that too many evangelists were simply beating the air with their words, failing to make intellectual contact with those they talked with, especially those growing up after World War II and who were encountering major cultural shifts in the early sixties. One could not simply appeal to the emotions and the heart when preaching. One had to consider the head as well, and what was going into it. To simply preach “Jesus saves” without first giving content as to who Jesus was and then addressing the cultural context into which the good news of the gospel was being preached was not to do justice to the gospel. Christian proclamation must have content; it must also appeal to the mind. History ultimately proved him right.

Schaeffer set out not only to preach the gospel but also to give good and sound reasons why the Christian faith was true against all intellectual comers and cultured despisers. Even his evangelical detractors, who thought he was attempting to analyze and answer too much in fields he had only marginal knowledge about, grudgingly admired Schaeffer for speaking out at a time when so many were either silent or merely reacting to the culture with more and stricter prohibitions on what they thought evangelical Christians ought or ought not to do. Furthermore, Schaeffer was not primarily concerned with getting people “saved” but in establishing sound reasons as to why Christianity was true and should be believed. He had been deeply influenced by the Dutch presuppositionalist philosophers Herman Dooyeweerd and Cornelius Van Til, as well as the Princeton theologian J. Gresham Machen and Fuller Theological Seminary apologist E. J. Carnell.

Schaeffer was a beacon of Reformed Christian light in a Europe moving rapidly towards postmodernism. He was asking and attempting to answer the big questions, and he refused to be locked into North American fundamentalist disputes. He had little time for small talk. I rarely saw him laugh. He took life very seriously and saw little value in humor for its own sake.

During the Christmas break in the winter of 1965, I decided to go to L’Abri Fellowship to see and hear Schaeffer for myself. I was curious, fascinated, and not a little in awe of this Christian “guru” tucked away in the Swiss Alps.

I flew to Geneva and made my way through the mountains by train to the French-speaking canton and the small village of Huemoz-Sur-Ollon. A group of wooden chalets huddled precariously against the rocky face of awesomely beautiful Swiss mountains. The name L’Abri meant “Shelter,” and the chalets were home to a number of families and American students. The chalets were “parented” by the married children of the Schaeffers themselves.

A church had been built on an even more precarious rock face, and it was here that Schaeffer preached some of the most powerful sermons I have ever heard. It would be true to say that this articulate and impassioned American Presbyterian was one of the best preachers of our time, uncompromising in his stand for historic Christianity.

Among the disciples of Schaeffer was the brilliant and articulate British sociologist and philosopher Os Guinness, who would later go to the United States to advise an American president and become himself a serious critic of Western culture through numerous books and publications and his own organization, the Trinity Forum.

My time at L’Abri was memorable though brief. Not only was Reformation theology being espoused and defended against existential despair, but I also received my first introduction to a Christian community. On reflection, I think that L’Abri, as a Christian community, was in some ways a more powerful apologetic statement than all the theology and philosophy that flowed from Schaeffer’s tapes and lectures.

Another dimension that was new to me and many others, both scholars and students, many of whom came from the United States, was the whole idea of Christian community and the common life that all those at L’Abri were attempting to live out and for which there were few if any models in contemporary Protestantism. Furthermore, Christian counseling, a relatively new idea, was in place, with private sessions being offered by a fellow New Zealander, Sheila Bird, nicknamed “Birdie” by her friends. Not only were the legalisms of kids from North American fundamentalist homes explored, documented, and addressed, but the demonic was also challenged and brought under the authority of Jesus Christ. Hundreds of students were helped and freed from a variety of bondages through her able counseling. Birdie made a difference not only to my own life but also to many who sought her wise counsel.

My time at L’Abri was all too short. I heard Schaeffer speak, listened to a number of his tapes, and was permitted an opportunity, just once, to speak with him privately. During our brief time together I asked him if he would be interested in meeting with Malcolm Muggeridge. He said he was, and would readily accept an invitation for himself and his wife the following summer if I would set it up. I agreed to do so.

I journeyed back to England and went straight to Robertsbridge, Sussex, for a weekend with Malcolm and Kitty. Over dinner I broached the subject, and both said they would like to meet the Schaeffers, having heard about them, and so a meeting was arranged for the following summer at Ashburnham Place.

At the end of my term in London and with exams completed, I took the train to Battle, Sussex, and made my way over to Ashburnham. I told the Reverend Bickersteth of my plans, and he and his staff were more than happy to oblige in making the necessary arrangements to have the Muggeridges and Schaeffers meet and talk.

On the arranged day the Muggeridges motored over from Robertsbridge, and the Schaeffers, who had flown in from Geneva, came down from London by car. It was an auspicious meeting. Despite the significance of the occasion I felt a little uneasy, as I was unsure how things would go and whether or not I had done the right thing in bringing together two men from such enormously different backgrounds. Both men’s wives, Edith and Kitty, were present.

The Rev. John Bickersteth arranged for us to sit on lawn chairs in the hedged garden for privacy, and his staff brought us tea and scones. I preferred myself to sit on the edge of the lawn, apart from both couples, to watch the interplay between the two men and listen to them talk.

I had high hopes for this meeting. I did not know exactly what to expect, but somewhere in the back of my mind was the hope that perhaps Malcolm would grasp the essential historic nature of Christianity. I looked forward, in any event, to a vigorous dialogue.

After brief introductions, Schaeffer immediately launched into a strident defense of historic Christianity, starting with the Reformation. It was Schaeffer at his best and most erudite. He hammered home the fact that Christianity was a closed-end system and could not be understood apart from history. He used the Bible and history to drive home his points. The only reason, he argued, to be a Christian was because it was verifiably true.

By way of response, Muggeridge made it clear that the facts of Christianity were only of marginal interest to him and did not touch the core of what it meant, for him, to be a Christian. Its truth, he said, did not rest on historical facts as such but in the drama of the Incarnation, God becoming man, a drama that each one of us played out in our own lives, much like a Shakespeare play in which all of us have our staged entrances and exits.

Muggeridge simply could not conceive of facts being either necessarily relevant or always truthful. He had learned, over the course of half a century of knockabout journalism, that the facts of a case did not always tally with the truth. Facts and truth were not necessarily the same. Truth, he said, transcended facts. It was simply not important to him that the Jesus of history was the Christ of faith. Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection transcended all such categories. He did not deny the facts, but saw them as largely irrelevant to the truth of what Christianity was about. The great truths the Church had enshrined through many centuries were artistic truths, which he considered much more truthful than any other kind of truth. Muggeridge said that for him, embracing Christianity was a question of faith, not rational proof, but it was, at the same time, a reasonable faith. If one accepted the initial hurdle of the Incarnation, everything else followed.

As far as the Incarnation is concerned, I believe in it, said Muggeridge. “I believe that God did lean down to become Man in order that we could reach up to him, and that the drama of the Incarnation described in the Creed did take place. And I accept the drama as the key factor in the whole story. If you say to me, ‘Do you believe that Jesus’ birth was by a virgin?’ I would say, yes, I do, because I think the whole drama requires that. But that’s entirely different from saying that I believe that a particular female, without anything else happening, conceived and bore a child and that that child was Jesus. In other words, I see it as an artistic truth rather than an historical truth. I think the Church began to destroy itself when it sought its evidence in historicity or in the process of science. The great truths the Church has enshrined through many centuries are artistic truths, which are much more truthful than any other kind of truth. The worst that could happen to the Christian religion would be for it to be provable in humanistic terms. It would be disastrous. For me, embracing Christianity is a question of faith, not of rational proof, but at the same time a reasonable faith; provided one accepts the initial jump of the Incarnation, everything else follows.”

This was like a red rag to a bull, to Schaeffer. He in turn stoutly defended the absolute necessity for Christianity to be understood, accepted, and grounded in history and its creedal formulations as a religion without equal, distinct and separate from all other religions by history.

Schaeffer was deeply concerned and not a little frightened by the implication of Muggeridge’s thinking. He saw Muggeridge’s position as reflecting the perspective in Salvador Dali’s surrealist painting, Christ of Saint John of the Cross, with the cross of Christ detached from the world and floating freely in the universe without reference to time or space.

This was, to Schaeffer’s mind, a form of nonrational mysticism that was enormously dangerous in both art and theology. Schaeffer saw in Muggeridge’s understanding of the Christian faith a form of free-floating mysticism that, if not moored to biblical truth, would not be open to verification. Muggeridge’s thinking was, to Schaeffer’s mind, a leap of faith without content, an easy step into impersonal mysticism and ultimately a contentless Christianity leading to despair.

As I watched and listened, I saw the two men sailing right by each other, neither really hearing the other or making contact with the other’s position. Each man’s understanding of the Christian faith was so vastly different from the other’s. On one side, Schaeffer, the American apologist and defender of historic Christianity, rooted in Calvin and the Reformation. On the other, Muggeridge, the convert from Socialism, worldliness, cynicism, and personal despair, coming to faith by experiencing and observing the world’s blueprints for peace and love producing just the opposite—war and hate. For him, the kingdom of heaven would never be found on earth; all such utopias and attempted utopias had failure built into them, their leaders bent on the acquisition of power rather than the desire to serve.

As the afternoon wore on, with each man struggling to claim the high ground for his position, I began slowly to sink into despair. One ray of hope entered the conversation when both men absolutely and totally agreed that abortion was morally wrong, indefensible, and would eventually lead to euthanasia. Muggeridge admired the Catholic Church’s staunch support of human life beginning at conception. Schaeffer pegged his belief in the right to life from God’s revelation as the author and giver of life. Later, Schaeffer would write A Christian Manifesto (1981), which defined abortion as the central issue for American society and called Christians to civil disobedience in the struggle against secular humanism that led to the degradation of human life. Both men deplored infanticide. It was the high point of the discussion, the only matter on which they both agreed.

Apart from this one area of agreement there was little the two men had in common. The dialogue soon became a monologue, a lecture by Schaeffer on the necessity for understanding “space and time history,” beginning in Genesis, moving rapidly from the Old Testament into the New, and taking quick historical leaps to the Reformation and to post-Reformation Europe, which was now, he said, devoid of biblical roots. He articulated his “line of despair” and what he saw as the failure of modernity to provide adequate answers for contemporary man’s spiritual predicament.

The history lesson soon had Malcolm slumbering. Kitty remained silent throughout. Occasionally Edith interjected her own thoughts on Christianity, which essentially parroted her husband’s but with a shrill edge. The truth is, I had never really taken to Edith, finding her rather self-possessed and little more than an echo of her husband. However, she did appeal to a lot of people and was regularly found on the evangelical speaking circuit in the United States.

As the afternoon wore on, I became increasingly aware of the growing distance between the two men. My tea grew cold, as did my heart. I felt helpless to do or say anything. I listened with growing anxiety at the yawning and increasingly unbridgeable gulf between the two men.

Part of me wanted Schaeffer to shut up and listen more, something I thought he was never very good at doing. My other instinct was to try to shake Muggeridge into the realization that a faith not grounded in history had dangerous implications both for himself and for millions of his radio listeners and television audiences.

On the one or two occasions Muggeridge managed to interject anything, it was to defend Christianity as true from a highly personalist point of view. He had found Christianity to be true not only by a process of elimination but also because everything he had tried or observed had quite simply failed. Socialism, Marxism, Nazism, Fascism, and various forms of nationalism, as well as materialism and promiscuity, had all been tried and found wanting. The dust of death was in all of them. And all of them had occurred in his lifetime, and he had to some degree or other personally experienced them all. By simple deduction, all that was left for him was the faith he had summarily rejected as a youth, influenced largely by his Socialist MP father and the later Fabians.

Muggeridge also spelled out his profound disappointment with the Anglican Church because it, too, he said, had capitulated to modernity in such areas as birth control and abortion and was no longer a fit place to hang one’s spiritual hat. He greatly admired the Roman Catholic Church and the current occupant of the see of Rome, and it was clear that he yearned for a spiritual place to call “home.” Later, he would meet with John Paul II at the invitation of the distinguished conservative American commentator William Buckley. But, like so many aesthetes, he found Catholicism untenable because of the Church’s numerous doctrinal positions, among them papal infallibility, which failed to make any sense to him and which ran counter to his own very modern mind. He saw the Church as another institution bedeviled by power, led invariably by the wrong people. Ironically, both he and Kitty did an about-face and were baptized into the Roman Catholic Church toward the end of their lives, deeply influenced in that decision by the faith and testimony of the Catholic Church’s second-greatest mother, Mother Teresa.

As I listened that warm, sunny afternoon, I recalled an earlier occasion, when an audience participant on a radio show called “Any Questions,” on which Muggeridge was a frequent guest, asked: If Muggeridge had been born in India and raised as a Hindu, would Hinduism be his religion of choice? Muggeridge replied that had he been born in that country, he would undoubtedly have been a devout Hindu. However, because he had been born into Western Christendom, it was in Christianity and Jesus Christ that he found meaning and faith.

I wished I could have, at some level, dismissed the differences between the two men as those of two radically different personalities based on some Myers-Briggs personality ratings. But it was much more than that.

For Muggeridge, the story of Christianity, with its implicit rejection of worldliness, materialism, and concupiscence, and its truth realized in the otherworldly figure of Mother Teresa of Calcutta, summarized for him what Christianity was all about—a rejection of all that this world had to offer in money, sex, or power, the raised fist or the raised phallus.

For Francis Schaeffer, the system of Christianity, with its doctrinal formulations rooted in Scripture, had to be defended at all costs. To relinquish truth at any level was to descend down the slippery slope to liberalism and modernity into a world without the safety net of God’s clear propositional word to man found solely in Holy Scripture.

At about four in the afternoon, the party broke up. Each couple made the appropriate-sounding noises about how wonderful their time together had been. But I knew in my heart that it was not true. The meeting had been an unmitigated disaster. I had bungled badly in bringing the two men together.

The sun still shone that early summer day over the quiet Sussex countryside as I accompanied them back to their cars, but I felt dark and bleak within.

I promised to see Malcolm and Kitty as soon as I could get away from my studies. I never saw Francis Schaeffer again. Years later, following his death, his wife Edith appeared in Vancouver, British Columbia, to give her “Walk Through the Bible” talks at a number of churches. I was religion editor of a daily newspaper at the time, but I didn’t have the stomach to hear her. I heard later that she appealed strongly to her audiences, even though her lectures ran for at least two hours at a time.

Later, when I dropped by the Muggeridges’ cottage for dinner, I broached the subject of the Schaeffers’ visit. When I asked them what they thought of their time with them, Malcolm and Kitty were gracious in their response, saying very little, possibly not wanting to hurt my feelings. But it was not a meeting that would ever be repeated. In my heart I knew that was true.

How we do evaluate the debate between Muggeridge and Schaeffer in the light of a fast-moving postmodernity? Schaeffer was clearly right in his observation that with the departure from “absolute truth,” theological and spiritual chaos would follow. Postmodernity, with its loss of the transcendent and its divination of the human, its replacement of the worship of God in concrete creed based on revealed truth for religious emotion in heightened personalist forms, is now almost completely realized. Schaeffer must be given credit for his insight into the loss of absolutes and a culture gone awry. He was and remains a prophet.

Muggeridge too, must be given credit for his prophetic stance that communism would fail and that the mass media and entertainment industry would be largely responsible for the moral breakdown of Western Christendom. Both men judged the culture accurately, each from his own perspective.

Muggeridge’s understanding that life is a dramatic performance is also true. We each enter the stage to play out our all-too-brief roles, then exit. Facts are not enough. They can mislead or be manipulated. Cameras blink. But Muggeridge’s theological rootlessness and his cavalier attitude toward Christian doctrine provided little of lasting value to prevent the wholesale explosion of postmodernity in England today. The country reflects only a shadow of its former spiritual glory, and the Anglican Church is dying, made largely irrelevant by theological compromise and increasing heterodoxy. His legacy as a writer, seer, and critic of culture will be his lasting legacy.

Schaeffer’s insights and his drive for a firm foundation for Christian belief will endure even in the face of watered down theology and clerics who compromise in the face of withering cultural scorn. The biblical worldview that Francis Schaeffer fought so valiantly for will have to be recaptured if it is to reshape the postmodernist landscape into which we have all now plunged. Only time will tell. The immediate forecast is not at all promising, though many, like myself, see movement toward a realignment of the theological plates as we approach the next millennium. n David Virtue (“The Collision of Two Minds”) grew up in New Zealand and has studied at Victoria University, the University of London, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Illinois, and Regent College, Vancouver, B.C. He has served as a staff writer for a number of Christian organizations and publications and is the author of two books on Christian faith and justice. He lives with his wife Mary in West Chester, Pennsylvania. They are practicing Episcopalians.

This article originally appeared in the New Zealand Christian journal Stimulus and also forms a chapter of the author’s forthcoming book Dear Boy: A Memoir of Malcolm Muggeridge.

David Virtue grew up in New Zealand and has studied at Victoria University, the University of London, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Illinois, and Regent College, Vancouver, B.C. He has served as a staff writer for a number of Christian organizations and publications and is the author of two books on Christian faith and justice. He lives with his wife Mary in West Chester, Pennsylvania. They are practicing Episcopalians.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor