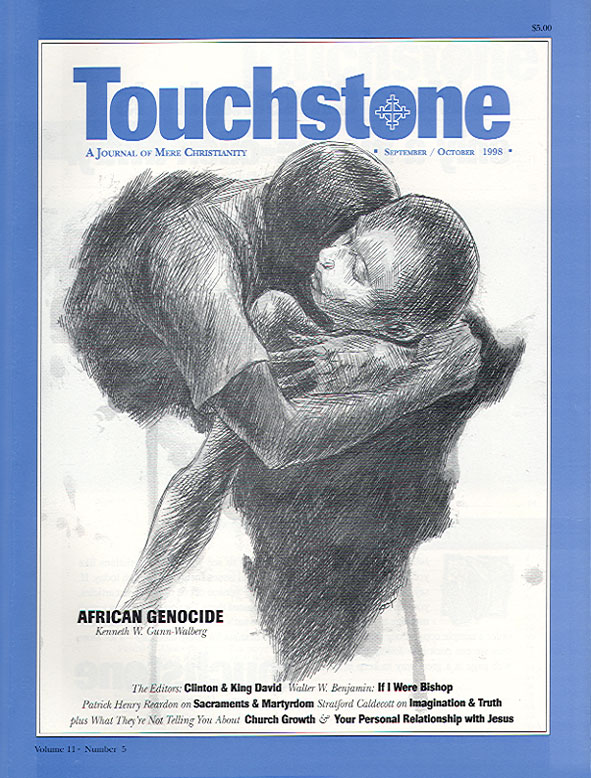

On Ecumenism

The Orthodox Churches & the World Council of Churchesby Peter Bouteneff with responses by S. M. Hutchens, David Mills, Gene Edward Veith, and Louis R. Tarsitano

The following is a shortened version of an article by Peter Bouteneff that was posted on the Internet by the WCC.

In 1920, long before the formation of the World Council of Churches (WCC), the ecumenical patriarchate addressed an encyclical “Unto the Churches of Christ Everywhere.” This was a call from the senior patriarchate of the Eastern Orthodox Church to all the Christian churches to overcome mistrust and bitterness, and to explore together the fellowship that exists between them even in spite of doctrinal differences. The encyclical called for several practical steps to be taken to bring churches into a closer relationship, including the inauguration of new relationships and exchanges across a broad spectrum of church life. Among these practical suggestions was that a “league” or “fellowship” be set up, following the example of the recently established League of Nations.

The Orthodox were thus a central part of the “ecumenical stirrings” at the beginning of the twentieth century, and helped to encourage the formation and continuation of the movements that would combine forces in 1948 to form the World Council of Churches.

Only seven years after the encyclical, the Orthodox delegation submitted an official statement to the First World Conference on Faith and Order at Lausanne in 1927. At this inaugural conference of the Faith and Order Commission, the “theological wing” of the ecumenical movement, the Orthodox said that while they came and participated “inspired by a sincere feeling of love and by a desire to achieve an understanding,” they regretfully found that the bases of the official reports were inconsistent with the self-understanding of the Orthodox Church. For this reason, they felt compelled to abstain from voting at the conference.

From the very beginning, then, the Orthodox have had a relationship with modern ecumenism that is characterized by enthusiasm and by discomfort, by encouragement and criticism, by joy and sorrow.

These are critical times in the encounter between the Orthodox churches and the WCC. A painful sign of the tensions that seem to be increasing in current years was the withdrawal from WCC membership of the Orthodox Church of Georgia in May 1997. Without exception, all Orthodox churches today are in the process of serious reflection among themselves concerning the nature and purpose of their participation in institutionalized ecumenism. What are some of the tensions being experienced?

The Orthodox Situation

Many difficulties arise out of recent dimensions on the political sphere. The fall of Communism has resulted not only in a sudden increase of religious liberty and opportunity that has led to a renaissance of spirituality and church life, but also a rise in nationalism and xenophobia that impedes receptivity to ecumenical endeavors. Among Orthodox in the West, other considerations can conspire to foment suspicion or hostility towards inter-Christian cooperation: emigrants from predominantly Orthodox countries, and also converts from non-Orthodox churches, sometimes define their Orthodox identity by emphasizing what they are not, as much as by stressing what they are. To all of this one can add the increase of fundamentalism, which is felt worldwide and across confessional lines.

The WCC Climate

Many Orthodox have increasing difficulty aligning themselves with what they perceive as the character and agenda of the WCC. When theological, sociopolitical or moral-ethical themes are discussed, some feel that there appear to be virtually no limits to the diversity that is tolerated. To many, although the WCC does not draw up or dictate policies of its own, there is a de facto tendency to place more conservative moral or theological positions on the defensive. Worship services in ecumenical settings can tend strongly towards a character that is quite foreign to Orthodox sensibilities. In all, Orthodox participants in the WCC feel that, thanks to a number of factors, they are a minority, sometimes even a special interest group, among a large Protestant majority.

None of the tensions or discomforts I have described is experienced uniquely by the Orthodox. But the Orthodox are the most clearly definable body of member churches that to some extent are experiencing them all, and furthermore, experiencing them to the degree that, as in the case of many churches, their very membership is under threat.

A Critical Assembly

If these are indeed critical times in the Orthodox encounter with the WCC, then the upcoming Eighth Assembly of the WCC, to be held later this year in Harare, will be a critical event. Together with the opportunities for fellowship and discovery presented by a happening such as this, all of the concerns set out above will have an opportunity to be aggravated. As at past assemblies, the worship events will alternately invite and alienate. There will again be no joint celebration of the Eucharist, for the Orthodox understanding of the Sacrament of Communion (as the highest expression of unity in faith) forbids the sharing of that Sacrament with non-Orthodox. This will again be a focus of pain for all sides.

The Harare Assembly will feature an open forum called the Padare (the Shona word for “meeting place”), and many of the concerns on display are liable to be difficult for many Orthodox to comprehend or appreciate. While the WCC officially is not aligning itself with the Padare offerings, the distinction between assembly visibility and WCC policy will not readily be grasped. The difficulties in this area have begun already: certain churches, for example, have reacted strongly against the WCC’s sanction of Padare offerings presented by openly gay groups.

On the hopeful side, the WCC’s most recent policy statement, “Towards a Common Understanding and Vision of the WCC,” is a careful and thoughtful piece that reflects also a process of restructuring affecting all levels of WCC activity. This process of taking stock and taking action, which will be discussed and adopted at the assembly, could bear the fruit of a more mutually fulfilling relationship between the Orthodox churches and the rest of the WCC.

The upcoming assembly in Harare will be attended and observed by the Orthodox with a blend of hope and apprehension, acceptance and criticism—that paradoxical blend of enthusiasm and consternation that we now know is nothing new. But we also now know that the tensions are running at an all-time high.

Why Remain?

From the somewhat bleak picture I have painted, one could reasonably ask whether I think that the Orthodox should remain members of the council. The answer is yes. The work for the full visible unity of Christians is holy work. Even as we Orthodox locate the Universal Church within the communion of our Church, it would be impious not to look outside our church boundaries to see, to affirm, and to engage with all that is real and true and beautiful there—all that is of Christ. We all share a responsibility before God to seek to discern what in our Christian disunity is due merely to misunderstandings and historical-cultural factors, and what needs addressing on the level of theology and life. All of this can be done to some extent without the World Council of Churches. But the WCC is a unique instrument, the most comprehensive global fellowship we have.

The Orthodox who are ambivalent to the ecumenical endeavor often forget how much their churches benefit materially from assistance rendered by or through the WCC. Aside from this prosaic but significant fact, our encounter with other Christians assists us in the much-needed renewal of our church life today. When we come before inter-Christian forums preaching our glorious theology, we know that our failures to live up to it are in full view. And much as we hate to admit it, many items that are squarely on the sociopolitical and moral-ethical agenda of WCC activity need to be placed more centrally on our agenda as well.

The relationship between the Orthodox and the World Council of Churches has its hopes and problems stemming from all sides. But may this relationship continue, boldly, courageously, with all honesty and goodwill!

Response from S. M. Hutchens:

Orthodox participation in the WCC has given the organization a dignity that Protestants who hold to traditional standards of doctrine and morality have in general been unwilling to grant it. The Orthodox, while treated with a modicum of respect in the WCC, are fundamentalists, along with us, by the common standards of its constituents. Orthodoxy’s patience and goodwill as part of the ecumenical project are admirable; some of the WCC’s work has been useful and enlightening. But if the Orthodox would find vital and meaningful Christianity among Protestants, it must descend to those who cannot or will not have a part in the WCC.

This is why statements such as this from Orthodox representatives are ambiguous to people like me—who may on this point represent conservative Protestants pretty well. When Orthodoxy addresses the WCC, it is addressing another party—liberal Protestantism—which has been persecuting us and stealing our lands for many years now. The tone and contents of Peter Bouteneff’s article are truly gracious, but at the base of it all there appears to be a lack of understanding of how things stand in these environs.

I am not blaming anyone for this, for it is easy to see how it could happen. I am just remarking on what appears to be the case.

Response from David Mills:

I would add to Steve’s comments that in my observation the Orthodox can get away with being so conservative in the WCC because modern Protestant liberals treat them as primitives or exotics. They tend to assume the Orthodox commitment to the Tradition is ethnic and cultural, a product of their historical development—e.g., in places like Greece as opposed to Germany—not a doctrinal conviction that spans ethnic groups and cultures.

I’ve heard this line taken especially on the Orthodox opposition to women’s ordination. Which means, among other things, that while the Orthodox may think they are having an influence, any stand they make for orthodoxy that offends the liberal consensus is dismissed as just “their thing,” as an Orthodox peculiarity that they will someday get over. If they have an influence for good on doctrinal matters, I suspect the liberals are open to their influence because liberals don’t care as much about doctrine as about ordaining women, and they further believe that all doctrines are just metaphors anyway, so why not let the Orthodox have their way?

Response from Gene Edward Veith:

Though the World Council of Churches may have been a good idea at one time, it has become, in effect, the World Council of Unorthodox Churches. The Orthodox Communion is the only conservative church body that still belongs—there are no Catholics, no evangelicals, no confessional Lutherans or Reformed, only denominations that allow heterodox interpretations of Scripture, the Trinity, the Deity of Christ, Christian morality, and the like. While there are undoubtedly believing Christians in the organization and in the churches represented, the body as a whole can hardly be said to be giving a specifically Christian witness at all. In fact, the sort of ecumenism that is based on reducing the doctrinal content of the faith into a vague lowest common denominator that everyone—even non-Christians—can believe is surely harmful. The Orthodox churches have been brave witnesses in this climate, but the basis of their fellowship with the modernist and postmodernist liberal theologians represented on the council is surely puzzling. The former Soviet Union, of course, had an interest in the Russian church’s involvement, which was reportedly manipulated for its own ends, though the WCC joyfully cooperated by issuing position statements that supported Soviet propaganda. But those times are over, and it is time that the Orthodox Church divorce itself from the anti-orthodox World Council of Churches.

Response from Louis R. Tarsitano:

The WCC’s euphemistically titled “Fund to Combat Racism” has often been used in Africa as a “fund to combat Christianity.” As an old-style Anglican missionary friend complained to me some years ago, his parishioners were being machine-gunned on the way to church, in the name of “raising their consciousness,” by groups supported in part by the fund.

In the bizarre world of such ecumenism, it is my “fundamentalist” Orthodox friends who most strenuously oppose the participation of Orthodoxy in the WCC, even as they are the most likely among the Orthodox to have a kind word, or even to deign to speak, to other sorts of Christian traditionalists in their local communities. The depth of their charity corresponds to the depth of their faith, in a wonderful testimony to the reality of their Christianity.

Since I am a “fundamentalist” Anglican, we disagree, obviously enough, about certain details of how the Universal Church of Christ is to be manifested to the world, but we find a commonality in our belief that the Universal Church is Christ’s Body, and in our sense that many of our bishops and bureaucrats have interests that lie elsewhere. Much the same is true, as well, of our overlapping relations with Roman Catholic “fundamentalists.”

My hunch is that the irritant of institutional ecumenism has planted the seed of an ecclesiastical ecumenism among those who are least likely to compromise their faith or their tradition. Whether or not this develops into a “pearl” of visible unity will be a matter of Providence, grace, and patience. In any case, institutional Christianity, as represented by the WCC, and ecclesiastical Christianity, as represented by the “fundamentalists,” continue to diverge.

Dr. Peter Bouteneff is a member of the Orthodox Church in America and Executive Secretary within the Faith and Order division of the WCC.

Gene Edward Veith is Professor of Humanities and Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Concordia University-Wisconsin and Cultural Editor of World magazine. He is a member of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, and lives in Cedarburg, Wisconsin.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Orthodox from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor