Iron Curtain Called

One Day in a Life Made All the Difference

March 23, 2018

Just 11, but always curious about people and places, I had the previous semester finished publication of my first magazine, a semester-long assignment to not only write about a foreign country but make it a project, a 3-pronged folder thick with pages of text, pictures cut from magazines, maps, and captions. On the outside of the folder I wrote the name of my chosen country in four large letters: "CCCP" (i.e., the USSR).

So, on November 8, 1963, I was watching a TV show set in the USSR. It was unlike anything I had come upon for my report. I was riveted to the Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre production of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. It was based on the sensational novel of a 44-year-old mathematics teacher and new writer, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. My wide eyes were peeking under the Iron Curtain, along with millions of others.

The program notes:

Under Stalin, it was inconceivable that anyone could publish a book attacking Soviet injustice. But under Khrushchev, a limited but distinct thaw has taken place. Prime evidence of this change was open publication of One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich, an exposé of Stalin's labor camps where the author, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, himself did time. Tonight's adaptation of the novel is set in 1951 in Siberia. A group of prisoners persuade the authorities to transfer them to warmer work by promising to top the previous work record on the first day. But if they fail, it's back to laying barbed wire in the snow.

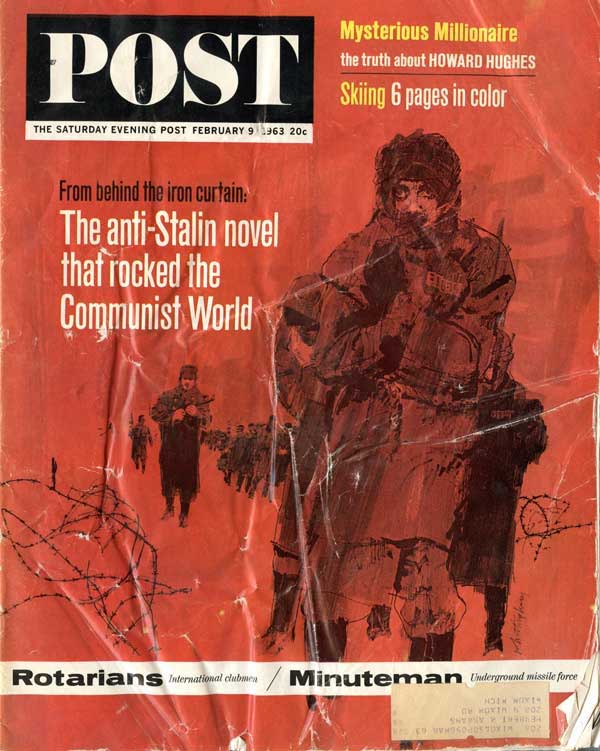

The book, published in November, 1962, made headlines and was featured on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, which published an excerpt. It had been rushed into English translation; in January 22, 1963 Harrison E. Salisbury reviewed it in the New York Times:

Suddenly, in Moscow, it would appear, everyone wants to write about life in the Stalin concentration camps. The reason for this is a rather short, sparsely told, eloquent, explosive, work by Alexander Solzhenitsyn which today reaches the American public in English translation.

Salisbury wrote, "This quiet tale has struck a powerful blow against the return of the horrors of the Stalin system. For Solzhenitsyn's words burn like acid."

The novel, understated as you might imagine it needed to be, was still "explosive," but truly so only in the long run. The fuse it lit burned slowly. Solzhenitsyn's writing career had been launched, but he would not bend to the Party; by 1969 he had been expelled from the Soviet Writer's Union and in 1974 from the Soviet Union itself.

In 1978 Solzhenitsyn gave the commencement address for Harvard, speaking for one hour through a translator. He thought he may have lit a fuse in the West, too, with his assessment of the spiritual state of both East and West and the needed remedies. But his unwelcome words burned some here like acid. (For a fascinating look at his address and its impact, stay tuned: the May-June issue of Touchstone includes "Schism in Harvard Yard" by L. Joseph Letendre. Hint: Subscribe today.)

There may be no iron curtains today, but there are veils and no-go zones when it comes to speaking the Truth. Solzhenityn saw them here in the West. There may be retaliation in various forms for transgressors of the secular regime.

How free do you feel to speak the name of the Lord, for example, in a faculty lounge, a board room, a medical treatment room, or at the news desk? If you feel free to do so, then you have leaped over a wall, broken through a fence, even if it will cost you at some point. But you are unafraid, set free by the Truth, and will not bend to the Party.

That wall, secularism's iron curtain, has been drawn in many minds, and is deeply set in the public square, which is a secularized no-go zone for references to Christ. Should you mention Jesus to a reporter, you will be ignored as if he were deaf; the next secular question will follow as predetermined as any computer program could make it.

But Jesus lives, and speaks, despite the fool-proof plans of the rulers of his day to silence him. On Palm Sunday be began to light a fuse—he was the fuse, the bomb, the explosion of Resurrection life that penetrates the dark world today lying under the curtain of the prince of this world, planting hope that will not disappoint. One day, Solzhenitsyn saw the light of Christ in prison, and it set him free. Many have had such eye-opening days.

Some of us may have Russian friends who knew Soviet times as children, but were able to peek wide-eyed under the iron curtain when candles were lit at church, at Pascha when "Christ is risen!" resounded in the hearts of believers. Christ is our bond. Our love. Our glory. One day in his life saved the whole world, Russians and Americans included.

Wishing you a Blessed Lent, and Holy Week.

Yours for Christ, Creed & Culture,

James M. Kushiner

Executive Director, The Fellowship of St. James

—James M. Kushiner is Executive Editor of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, and Executive Director of The Fellowship of St. James.