The Fixed Pains of Hell

C. S. Lewis’s Defense of the Doctrine of Eternal Punishment

The Dominical utterances about Hell, like all Dominical utterances, are addressed to the conscience and the will, not to intellectual curiosity. . . . I could not pay one ten-thousandth of the price that God has already paid to remove the fact. And here is the real problem: so much mercy, yet still there is Hell. —C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain

C. S. Lewis was perhaps the most influential lay theologian of the twentieth century. His work in apologetics famously helped lead to the conversion of Chuck Colson and has been an influence in the preservation of the faith of countless others in times of doubt. His Chronicles of Narnia have made Christian doctrine come alive for untold thousands. He mounted a brilliant and often insightful defense of traditional, supernatural Christianity that fully justifies his continuing popularity among the faithful.

Because Lewis was a popular and influential defender of classical orthodoxy, it is worthwhile taking a fresh look at his defense of the classical doctrine of eternal punishment. Lewis did not deal directly with annihilationism or conditional immortality because in his lifetime those doctrines were mainly confined to cults, and Lewis concentrated on what he called “mere Christianity.” Nevertheless, he does speak of hell and of the nature of the soul in ways that lend themselves to a defense of eternal conscious punishment. He addresses universalism only indirectly, but clearly denies it, defending the idea that there is a hell and there will be people in it, and in it finally. We will start, then, with a treatment of Lewis’s general eschatology and then move on to focus on its implications for those two currently trending denials of the traditional view.

The Necessity of Choice

In Lewis’s view of personal eschatology, the overriding emphasis is one we could express with one of his book titles: The Great Divorce. As he explains in the preface, that title is a response to Blake’s “Marriage of Heaven and Hell” and the general tendency it represents to deny that reality ever “presents us with an absolutely unavoidable ‘either-or.’” Today the same impulse manifests itself in the fad of pretending to be “non-binary.” By contrast, Lewis’s “great divorce” is that between Christ and Satan, which is a choice between good and evil, leading to a choice between heaven and hell. The two sides of those pairs are not the same, and every human being is unavoidably faced with an irrevocable choice, an “absolutely unavoidable ‘either-or,’” between them.

Lewis thus echoes the biblical motif that “it is appointed unto men once to die, and after that the judgment” (Heb. 9:27). The Great Divorce is ambiguous about whether the choice between heaven and hell can be made after death; George MacDonald’s spirit replies to the voicing of that question, “Ye were not brought here to study such curiosities.” But Lewis is always clear that the great business of life is to choose between God and anything else, with eternal consequences (heaven or hell) depending on that choice. MacDonald continues, “What concerns you is the nature of the choice itself: and that ye can watch them making.” Lewis’s mind is never far from two ideas: first, the inescapability of the choice, and second, how much it matters.

Ultimately, what we are choosing is either God or an idol. But while that choice may be made in a moment of spiritual crisis, it may also be made slowly and unaware throughout our lives, and we may not even realize what we have chosen until the end. Here is how the Narnians face their Day of Judgment in The Last Battle:

As they came right up to Aslan, one or other of two things happened to each of them. They all looked straight in his face. . . . And when some looked, the expression of their faces changed terribly—it was fear and hatred. . . . All the creatures who looked at Aslan in that way swerved to their right, his left, and disappeared into his huge black shadow. . . . The children never saw them again. . . . But the others looked in the face of Aslan and loved him. . . . And all these came in at the Door, on Aslan’s right.

One is reminded of Jesus’ language about the sheep and the goats (Matt. 25:31–46). There are but two paths, two destinations, and there is a final and irrevocable separation between them. How a person relates to Jesus (or Aslan) is the final determination of which path he is on, sometimes not finally revealed until the end.

One either ends up in Aslan’s country or in the shadow.

Evangelicals tend to be conversionists; that is, they expect conversion to be a very conscious decision, to involve a crisis experience when the sinner turns overtly and consciously from sin to Christ as the outcome of the process of conviction and calling. While Evangelicals would not insist that a stereotyped conversion experience is necessary to salvation, the expectation of something very like it tends to be their default setting. Lewis did not deny the role of such a conversion. Indeed, he seems to have had at least two such moments in his own journey to faith, one very definite one when he “gave in,” laid down his arms and surrendered, “admitted that God was God” and became a theist, and another, more subtle, one when he realized after a trip to the zoo that he now believed that Jesus was the Son of God (Surprised by Joy). But he put more emphasis on the smaller, cumulative decisions that may add up to those larger changes that define a life trajectory.

Every time you make a choice you are turning the central part of you, the part of you that chooses, into something a little different from what it was before. . . . All your life long you are slowly turning this central thing into a heavenly creature or into a hellish creature. . . . Each of us, at each moment, is progressing to the one state or the other. (Mere Christianity)

There are problems with this passage. One does not, indeed, cannot, turn oneself into a heavenly creature; only the grace of God can do that. And one does not need to change oneself into a hellish creature; we are already on that trajectory at birth unless the grace of God intervenes. But Lewis is right about two things: that “each of us, at each moment, is progressing to the one state or the other,” and that the choices we make flow from and confirm us in one trajectory or the other. He is therefore right to notice how significant those choices are, even the small ones. The fruit of them will indeed be the experience either of heaven or hell.

Perhaps someone’s sins—a hot temper or jealousy or lust—are getting only very gradually worse, so gradually that the change even in seventy years would not be very noticeable. “But it might be absolute hell in a million years: in fact, if Christianity is true, Hell is the precisely correct technical term for what it would be” (Mere Christianity). Hell, in other words, is not just an arbitrary judgment on our sins; it is the revelation of what they are in their essence, what they will become and make of us if unchecked by grace. One need not deny that hell involves retributive judgment to appreciate this insight. But it is a recognition that the choice of sin and rejection of Christ would become hell to us by the very nature of those choices even if we were not being judged.

Lewis labors long and hard to make sure his readers understand that there is an unavoidable fork in the road of life, that we have to choose one path or the other, that we do so choose whether we realize it or not, and, finally, that the stakes of those choices are nothing less than cosmic. He wants us to realize that the destiny of individual human beings is terribly important, much more so than the fate of even a nation or a civilization:

If individuals live only seventy years, then a state or a nation or a civilization, which may last for a thousand years, is more important than an individual. But if Christianity is true, then the individual is not only more important but incomparably more important, for he is everlasting, and the life of a state or a civilization, compared with his, is only a moment. (Mere Christianity)

Our very humanity is one of the things at stake: in heaven you will be more truly human than you ever were on earth, and in hell you will be essentially excluded from true—that is, redeemed—humanity (The Problem of Pain). But even greater than that, looming over all other concerns, is the relationship we human beings will have—or not have—with God. In The Weight of Glory, Lewis explains what he had portrayed in The Last Battle, when the Narnians meet Aslan: “In the end that Face which is the delight or the terror of the universe must be turned upon each of us either with one expression or the other, either conferring glory inexpressible or inflicting shame that can never be cured.” The beatific or the “miserific” vision: the difference is too great to put into words, but Lewis perhaps comes as close as one can:

In some sense as dark to the intellect as it is unendurable to the feelings, we can be both banished from the presence of Him who is present everywhere and erased from the knowledge of Him who knows all. We can be left utterly and absolutely outside—repelled, exiled, estranged, finally and unspeakably ignored. (The Weight of Glory)

Or we can be finally and forever welcomed home. Heaven or hell is ultimately the choice or rejection of God himself. “Union with that Nature [of God] is bliss and separation from it is horror. Thus Heaven and Hell come in” (Surprised by Joy). This is a “great divorce,” a great separation or distinction, indeed!

Lewis wants us to understand the great parting of the ways that lies ahead in eternity, but he also wants us to grasp the way in which this vision reaches back to illuminate our life in time. Not only is earthly life the arena in which such great matters will be decided, but our daily lives are also filled with meaning by that vision here and now. Lewis thought that earth, if preferred to heaven, would eventually be discovered to have been part of hell all along; while if it were put second to heaven, it would eventually be discovered to have always been the vestibule of heaven itself. (The Great Divorce). Heaven—or hell—does not have to wait for eternity. Foretastes of each begin already in this world. Like Jewel the Unicorn, when we reach Aslan’s country (or the other place), we will realize that the reason we loved—or hated—the old Narnia is that sometimes it reminded us of this (The Last Battle).

If, then, the great business of this life is to choose between the paths leading to heaven and to hell, it remains to discover what we can know about these destinations. We will here consider Lewis’s perspectives on hell.

The Fruition of a Choice

What is the nature of hell according to Lewis? It is the natural fruition of the choice of self over God as it has become fixed for eternity.

Consistent with Lewis’s emphasis on the Great Divorce is his view that people are in hell because that is what they have chosen. They might not have realized they were choosing it; they might have thought they were choosing something else; but hell is precisely the grand summation of all they have chosen. As the George MacDonald character in The Great Divorce explains, there are finally only two kinds of people in the world: “those who say to God ‘Thy will be done,’ and those to whom God says, in the end, ‘Thy will be done.’ All that are in Hell choose it.”

The latter probably did not say to themselves, “By Jove, I think I shall opt for eternal punishment.” They are more like Claudius in Hamlet, who wants to repent of murder and receive God’s forgiveness but cannot bring himself to give up the effects for which he did the murder: the crown, his own ambition, and the queen. They choose other things which they will not un-choose and which do, in fact, entail damnation. But to choose self over God is to choose hell, as Lewis explains:

Be sure there is something inside you which, unless it is altered, will put it out of God’s power to prevent you from being eternally miserable. While that something remains there can be no Heaven for you, just as there can be no sweet smells for a man with a cold in the nose, and no music for a man who is deaf. It’s not a question of God “sending” us to Hell. In each of us there is something growing up which will of itself be Hell unless it is nipped in the bud. (God in the Dock)

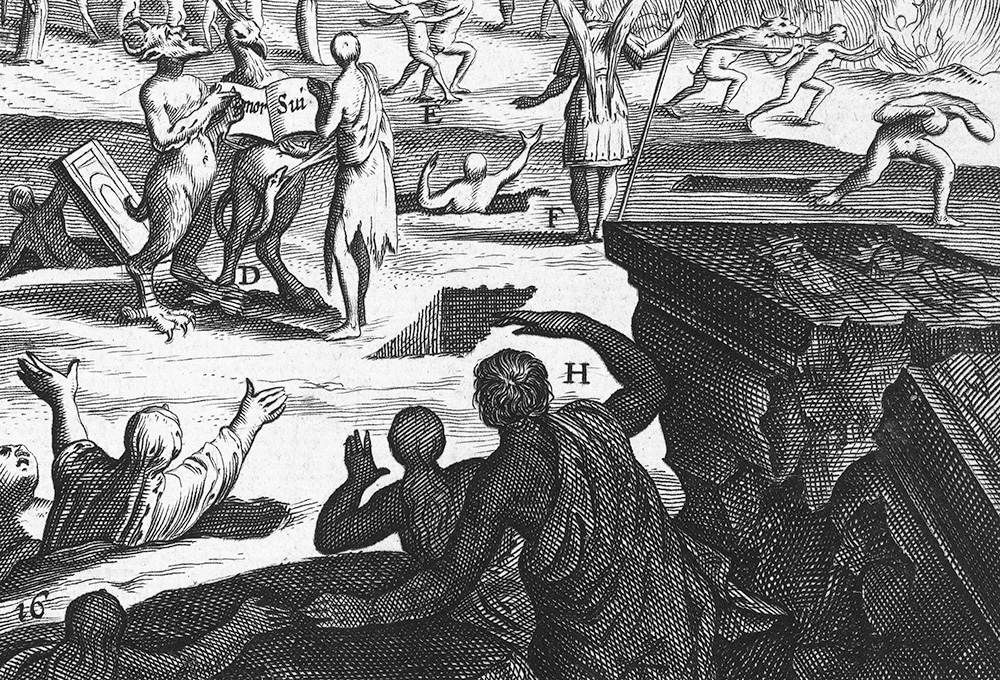

What is this hellish thing growing up inside us? The biblical designation for it is sin, the essence of which is rebellion against God. If heaven is the enjoyment of God’s presence and favor, then the rejection of God’s will and preference for our own—rebellion, sin—clearly excludes us from that enjoyment by its own nature. Hell, then, really is God saying, after all his offers to reclaim us have been refused, “All right, fine, thy will be done.” He will not redeem us by simply overriding our wills. That is why Lewis says, “I willingly believe that the damned are, in one sense, successful rebels to the end; that the doors of hell are locked on the inside” (The Problem of Pain). There comes a point when the will’s choice of itself over God is fixed and irrevocable, and that state is hell. That is why the faces in hell are “all fixed faces, full not of possibilities but of impossibilities” (The Great Divorce).

The spirit of George MacDonald notes that “the whole difficulty of understanding Hell is that the thing to be understood is so nearly nothing.” This does not mean that choosing hell is inconsequential or anything less than a colossal tragedy. Behind MacDonald’s statement lies Augustine’s doctrine of evil as a privation of the good: hell is the good of existence trying to return to nothingness and nearly succeeding. Also lurking in the background is Augustine’s definition of sin as being incurvatus in se, “turned in upon oneself” rather than being oriented outward to God. God is the Creator and Source of good, that is, of reality. To reject him and turn inside oneself in a search for the good is to turn toward nothingness, to turn away from a larger world. That is what the MacDonald character means when he later says,

A damned soul is nearly nothing: it is shrunk, shut up in itself. Good beats upon the damned incessantly as sound waves beat on the ears of the deaf, but they cannot receive it. Their fists are clenched, their teeth are clenched, their eyes fast shut. First they will not, in the end they cannot, open their hands for gifts, or their mouths for food, or their eyes to see. (The Great Divorce)

Surrounded by God’s loving presence (for none can escape it), such people are able to experience it only as judgment. The most chilling picture of hell may then be the state of the Narnian dwarfs in The Last Battle, who are in Aslan’s country but are cut off from the enlarging vistas of “further up and further in” because they are convinced that they are still in the dirty stable. Offered violets, they reject them as filth and straw. “You see,” said Aslan. “They will not let us help them. They have chosen cunning instead of belief. Their prison is only in their own minds, yet they are in that prison; and are so afraid of being taken in that they cannot be taken out.” A more profound picture of Augustine’s phrase could hardly be imagined. These dwarfs are incurvatus in se indeed.

The notion of hell as self-inflicted and the idea of earthly life as a preparation for either hell or heaven are combined in Till We Have Faces in the character of Orual as she hardens herself against her brief vision of Psyche’s palace, choosing ironically to walk by unbelief rather than by sight. Fortunately, she realizes her mistake at the end, but until then her life is a systematic attempt to turn herself into one of those lost dwarfs. “The nearest thing we have to a defence against [the gods],” she says, “is to be very wide awake and sober and hard at work, to hear no music, never to look at earth or sky, and (above all) to love no one.”

Looking back on her life, she explains, “I locked Orual up or laid her asleep as best I could somewhere deep down inside me; she lay curled there. It was like being with child, but reversed; the thing I carried in me grew slowly smaller and less alive.” It is as if she had been reading the analysis in The Four Loves: “The only place outside of Heaven where you can be perfectly safe from all the dangers and perturbations of love is Hell.” Augustine’s doctrines of evil as privation and of sin as being incurvatus in se could not be pictured more brilliantly, not just as abstract ideas but as life processes leading to a damnation which is their natural fruition.

The Question of Justice

The hardest thing to grasp about the traditional Christian doctrine of eternal punishment is perhaps its justice. How, skeptics ask, can unending punishment be just, no matter what the crime? Lewis takes this problem seriously and attacks it from multiple directions. First, as we have seen, he presents hell as self-inflicted, not as the arbitrary imposition of punishment by a vengeful deity so much as the natural fruition of clinging to the choice of allegiance to self. Then he also tries to spin hell as actually merciful. From Uncle Andrew to the dwarfs to Orual, he consistently pictures God as giving people all the mercy they are able to receive. God wants to prevent us from experiencing the kind of damnation Milton’s Satan undergoes:

Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell;

And in the lowest deep a lower deep

Still threat’ning to devour me opens wide

To which the Hell I suffer seems a Heav’n. (Paradise Lost IV.75–78)

To protect us from such a fate, Lewis thinks God has created hell as a limit below which we cannot sink. “The walls of the black hole are the tourniquet on the wound through which the lost soul would bleed to a death she never reached. It is the Landlord’s last service to those who will let him do nothing better for them” (The Pilgrim’s Regress). Or, as Lewis describes it poetically,

God in His mercy made

The fixed pains of Hell.

That misery might be stayed.

God in His mercy made

Eternal bounds and bade

Its waves no longer swell.

God in His mercy made

The fixed pains of Hell. (Poems)

There comes a point, we said above, at which the soul’s rejection of God for self becomes fixed. Actually, according to the Bible, that point has already been reached by all of us apart from God’s grace. “A natural man does not accept the things of the Spirit of God” (1 Cor. 2:14); we are not mortally ill but already spiritually “dead in our trespasses and sins” (Eph. 2:1) until we are made alive by Christ (2:5). Does God simply override our wills in changing this situation? No; he enables them to choose what otherwise they could not; in removing our stony hearts, he gives us a new nature, which now naturally desires what before it would have rejected, a choice in favor of God.

Lewis did not always make this point as carefully as he might have. In my view, it would have been more accurate to say that there comes a point at which the natural fixedness of our wills in sin is confirmed and the possibility of rescue from ourselves by grace is withdrawn. However we define it, though, he was right to think that such a moment can come, that hell is its result, and that understanding this is helpful in seeing the rightness of the classical doctrine. He expresses it with one of his helpful analogies:

I believe that if a million chances were likely to do good, they would be given. But a master knows, when boys and parents do not, that it is really useless to send a boy in for a certain examination again. Finality must come sometime, and it does not require a very robust faith to believe that omniscience knows when. (The Problem of Pain)

People who object to the doctrine of eternal punishment are understandably horrified by it. But in their objection, they often do not realize what they are asking. What would they have God do with those who persist in their rebellion?

The answer to all those who object to the doctrine of Hell is a question: “What are you asking God to do?” To wipe out their past sins and, at all costs, to give them a fresh start? . . . But He has done so, on Calvary. To forgive them? But they will not be forgiven. To leave them alone? Alas, I am afraid that is what He does. (The Problem of Pain)

Lewis asks, pertinently, “Can you really desire that such a man, remaining what he is . . . should be confirmed forever in his present happiness—should continue, for all eternity, to be perfectly convinced that the laugh is on his side?” The MacDonald character in The Great Divorce explains that what “lurks behind” the feeling that the damnation of one soul would render heaven imperfect is “the demand of the loveless and the self-imprisoned that they should be allowed to blackmail the universe.” For Lewis, the meaning of human choice is the bottom line. If choice is to be significant, it must be allowed to be significant. Lewis was always very clear about that. Those who choose against submission to God must be allowed to have what they have chosen, and to discover that “length of days with an evil heart is only length of misery” (The Magician’s Nephew).

Lewis Vis-à-vis Annihilationism

What do Lewis’s perspectives have to say about annihilationism? He does not address it directly. But it is clear that he conceived of hell as conscious and unending. He defines it as “eternal loneliness” (Mere Christianity). One must be conscious to be lonely. Screwtape advises his understudy demon Wormwood that if he is successful in his temptations of his “patient,” he “will have all eternity wherein to amuse yourself by producing in him the peculiar kind of clarity which Hell affords.” Wormwood’s anticipated “reward” clearly entails the continued existence and consciousness of his “patient.”

This view is not just an arbitrary opinion or a passive acceptance of traditional belief. It is consistent with Lewis’s emphasis on heaven and hell as the fruition of the soul’s choice. It is the nature and the destiny of the human soul as designed by God that it should experience in its fullness what it has chosen. The justice of hell for Lewis is seen, not in some judicial calculus of fitting some specific measure of intensity and duration of pain to specific offenses, but in the fact that each soul is given what it has chosen.

How does this relate to annihilationism? Well, has the unbelieving soul chosen non-existence? No. It wants to exist on its own, autonomously from God. Remember Lewis’s definition of the sin that constituted the Fall:

They wanted, as we say, to “call their souls their own.” But that means to live a lie, for our souls are not, in fact, our own. They wanted some corner of the universe of which they could say to God, “This is our business, not yours.” But there is no such corner. . . . This act of self-will on the part of the creature, which constitutes an utter falseness to its true creaturely position, is the only sin that can be considered as the Fall. (The Problem of Pain)

Had Lewis been confronted with annihilationism, he might then have argued that the appropriate response to sin as so defined is not annihilation at all, but rather the experience of what continued existence without God really is: continued existence separated from the Source of all that is good, true, and beautiful. The reprobate sinner cannot complain of injustice because he has been given what he chose to have. It is just and right because he chose it, and it is just and right because he is not allowed to avoid confronting, as a lie, the lie that he has preferred to believe. Here the words just and appropriate coalesce. It is ironic, then, that to affirm annihilationism, a position often held to try to avoid the perceived cruelty and injustice of eternal conscious punishment, one must give up what would appear to be one of the more powerful arguments in favor of God’s justice in his treatment of the reprobate.

The cogency of this argument against annihilationism depends on the accuracy of Lewis’s definition of sin. I would submit that it does an excellent job of encapsulating both the story of Eden and the definitions in the New Testament. We read that sin is lawlessness (1 John 3:4), that is, a refusal of God’s law, the choice to be a law unto oneself. We read that whatever is not of faith is sin (Rom. 14:23). Faith is an obedient trust in God’s goodness and faithfulness that causes us to cling to his promises, particularly his promise of forgiveness and salvation. Its opposite would be trust in oneself and consequent obedience to one’s own impulses. Lewis then can help us see one way in which the traditional doctrine of hell is not only biblical and just but also profoundly appropriate to the unrepented sinfulness of fallen men.

Lewis Vis-à-vis Universalism

Lewis might have been expected to have sympathy with the version of universalism taught by his spiritual mentor George MacDonald, in which there is a hell for the unrepentant, but it is not eternal; God’s love will eventually win over all its inmates and empty it into heaven. MacDonald thought God’s love must ultimately triumph, that the flames of hell were simply God’s love felt as fire from a distance until that distance is overcome:

Such is the mercy of God that He will hold His children in the consuming fire of His distance until they pay the uttermost farthing, until they drop the purse of selfishness with all the dross that is in it, and rush home to the Father and the Son and the many brethren—rush inside the center of the life-giving fire whose outer circles burn. (George MacDonald: An Anthology)

Consistent with this expectation is the ending of MacDonald’s novel Lilith, where the sleep of “good death” represents submission to God’s love, leading to the awakening which is true life. At the climax of the story, even Lilith goes to sleep. When she asks about the Shadow (Satan), she is told, “You and he will be the last to wake in the morning of the universe” (Phantastes and Lilith). This is surely the most “evangelical” version of universalism on offer. But is it what Scripture teaches?

Lewis thought not. He seems to have accepted the authority of Scripture and Christian tradition on that point. He reckons, as we have seen, not only with the eternity but also with the finality of hell. Its door is locked on the inside. The Master knows that at a certain point it is useless to send the pupil in for the examination again. When Lewis’s persona in The Great Divorce asks MacDonald’s spirit about the universalism he had held in life, it equivocates and digresses into a discussion of time and eternity which it says makes a straight answer impossible. Lewis seems to have realized that the Bible never clearly promises such an outcome but does warn us of the cosmic importance of the decision required of us in this life: “It is appointed unto man once to die, and after that, the judgment” (Heb. 9:27).

Lewis does not make an exegetical argument for this conclusion. It is rather a manifestation of the importance of choice in Lewis’s anthropology. The choices we make in this life matter, and they matter for eternity. They are that serious. Those who do not choose God choose eternal death, “and they must be allowed to have it” (The Great Divorce). Careless critics often label Lewis as a universalist, but he clearly was not. He was an inclusivist—but that is a different doctrinal issue for a different essay.

Insights for Contemplation

Lewis, then, was not a universalist. He believed that there is a hell and that some human beings will spend eternity in it. He wisely upholds biblical teaching on hell’s existence, but he does not speculate too much about what it is actually like (beyond the “suppositions” about the misanthropic ghost town in The Great Divorce). Lewis not only defends the justice of hell, but he argues that hell is ironically an expression of God’s mercy. In many contexts he presents it as the only form of mercy that stubborn sinners are able to accept. By and large, Lewis sticks to what Scripture demands and refrains from going beyond it. He leaves the mystery of the eternal fate of the wicked intact while portraying it convincingly as the natural fruition of their rejection of God as the supreme Good.

Lewis does not deny the judicial and penal aspects of hell, but he focuses on it as God’s merciful tourniquet on the universe’s wound of sin and as the fruition of the soul’s ultimate choice. These ideas are not mutually exclusive. God could use the fruition of the choice to reject him as the appropriate punishment for sin. This is perhaps one of Lewis’s most useful insights in that it gives us an original and interesting rationale for the justice and appropriateness of the traditional doctrine of eternal conscious punishment as a feature of Christian eschatology. These are insights worthy of our consideration as we contemplate the current controversies over the doctrine of the Last Things.

Donald T. Williams is Professor Emeritus of Toccoa Falls College. He stays permanently camped out on the borders between serious scholarship and pastoral ministry, between theology and literature, and between Narnia and Middle-Earth. He is the author of fourteen books, including Answers from Aslan: The Enduring Apologetics of C. S. Lewis (DeWard, 2023). He is a contributing editor of Touchstone.

Share this article with non-subscribers:

https://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=38-06-026-f&readcode=11303

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor