Positively Christian

Principles for Living in the Negative World

by Aaron Renn

Unlike Europe, America never had a state church. But for most of its history it had a sort of softly institutionalized generic Protestantism as its default national religion. This was still true as recently as the 1950s, though it had shifted towards being more of a generic Judeo-Christianity by that point. During that decade, about half of all adults attended church each week. There were still prayers and Bible reading in public schools. The country added “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance, and “In God We Trust” to its money.

Then, in the 1960s, this began to unravel, and the status of Christianity began to go into decline in America. This showed up in declining church attendance as well as in an increased questioning of the Christian moral system, such as with the Sexual Revolution. This is a decline that continues to the present day.

This period of decline, from roughly 1964 to the present, can be divided into three phases or “worlds,” which I call “the positive world,” “the neutral world,” and “the negative world” (according to a model first published in my February 2022 First Things article, “The Three Worlds of Evangelicalism”), enumerated as follows:

• The positive world (1964–1994): Christianity is in decline. All is not well for the faith. Yet it is still basically viewed positively. To be known as a good churchgoing man makes someone seem like an upstanding member of society. Christian morality still forms the basic moral norms of society, and transgressions against it, such as a politician having an affair, can be costly.

• The neutral world (1994–2014): Christianity is no longer seen positively, but it is not yet seen negatively either. Being a Christian is just one lifestyle choice among many in a pluralistic public square. Christian morality has a certain residual hold on society.

• The negative world (2014–present): For the first time in the 400-year history of America, official, elite culture now views Christianity negatively, or at least skeptically. To be known as a Bible-believing Christian is a potential negative in elite domains of society. Christian morality is expressly repudiated and is even in some ways seen as the leading threat to the new public moral order.

The recent shift to the negative world has been very dislocating to serious American Christians, who have struggled to adapt to this new landscape because their strategies had largely been developed and tuned to the cultural conditions of the positive and neutral worlds. Until recently, ideas pitched towards the idea of the negative world, as in Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option, were greeted skeptically. This was also true of similar but more aggressive ideas that originated with Reformed pastor Andrew Isker and became known as the “Boniface Option,” named after the saint who converted a Germanic tribe after chopping down its sacred tree.

Thus far in the negative world, instead of new strategies, we have seen deconstruction, realignment, deformation, and conflict in American Christianity. Some people have abandoned their faith. Others have changed tribes or political alignments. Still others have doubled down on their existing approaches in ways that have become deformed under the pressures of the negative world. The net result has been intra-church conflict. Whereas previously the culture war was between secular society and the church, today it has moved internally to the church, often polarizing around positions on Donald Trump and race.

Principles for Navigating the Negative World

While most Christians today seem to accept the idea that we live in a negative world, there is significant disagreement over how to respond to it. It’s unlikely that there will be, or even should be, just one or two approaches to living in the negative world. So rather than put forward yet another strategy, I will instead lay out a series of guiding principles that any successful and healthy strategy should embody.

Principle #1

Do not fall prey to ressentiment.

In his works on the culture wars, most recently Democracy and Solidarity, sociologist James Davison Hunter notes how both sides of the culture wars have fallen prey to ressentiment, a Nietzschean concept that Hunter defines as “a narrative of injury that seeks revenge through a will to power.” Ressentiment is not a result of some particular, discrete harm that one has suffered, but rather a general sense of inferiority or woundedness. This sense may be rooted in a genuine injustice but has overflowed the bounds of simply being wronged. As a result of this pervasive sense of ressentiment, Hunter writes:

Outrage against a grievance caused by others, then, becomes the source of authentic identity and authentic action. In this strange calculus, the more rage the better. In turn, rage, hatred, and the desire for revenge that emanate from injury become the source of meaning and purpose for those who see themselves as victims.

He notes that both conservatives and liberals suffer from this mindset.

Christians in the negative world must avoid falling prey to the logic of ressentiment. Rather than repaying evil for evil, we must overcome evil with good, loving our enemies and being joyful in the face of unmerited suffering. We must have a positive identity rooted in who we are rather than a negative one rooted in whom we are against—or worse yet, whom we hate.

Principle #2

Do not try to turn back the clock.

In a world that seems to have gone mad or at least very poorly from the perspective of the contemporary American Christian, it can be tempting to retreat into the past. Indeed, in an era that’s been described as “liquid modernity,” we see many people looking backward in search of solid ground on which to stand. This manifests itself religiously in many ways, including increased interest in the Latin Mass in the Catholic Church, the turn to Eastern Orthodoxy, and the draw of more liturgical traditions like Anglicanism among Protestants. I personally am part of this: raised low-church Pentecostal, I have been drawn to more traditional Presbyterianism, preferring old churches, classic hymns, and formal liturgies. We see this trend also in the non-religious world, with the homesteading movement and the “trad wife” phenomenon, to name two examples. It’s self-consciously retro and escapist.

Rightly understood, this impulse is correct. This is a time to consider our ways and reflect on where we may have strayed from the right path. Anchoring ourselves in the historic faith and its practices is one way we can seek to correct our course in places where we might have gone astray. We can see that there are good things that have been lost with social changes, and seek to recover them.

But this can be taken too far. We cannot return to the Christianity of a previous era. Pre-Vatican II Catholicism cannot be restored. Mainline Protestantism of the 1950s is not coming back. Some conservatives today seem to be driven by a deep sense of alienation from the world in which they live. They want to reject the world, not in the sense in which the Apostle John speaks of it but in terms of the actual environment in which we live. Whatever the problems with modernity, the industrial age, technology, or liberalism—and there are many—we cannot escape them by returning to a previous age. They are the inescapable conditions of our present reality.

An example of an excessive retro turn can be seen in manifestations of the “courtship” movement that seek to bring back a historic form of matchmaking. There’s much to dislike about online dating and the whole of today’s dating environment. It is good for parents to play a more active role in helping their children find and marry a suitable person. But attempting to recreate a culturally bound courtship approach from the past is likely to create as many problems as it solves.

The past is not a fixed template that we should attempt to replicate. As Baptist political scientist Benjamin Mabry puts it in “Against the Antis” (Aaron Renn Newsletter, June 25, 2024), “The tradition gives us resources to apply to current situations, not precedent to blindly apply without consideration.”

Principle #3

Do not become a prisoner of the postwar consensus.

Many American Christians de facto believe that the American postwar, post-civil rights, liberal consensus is what Christianity mandates as a socio-political system. They are incapable of thinking outside this box. We see it in how they respond to people who critique it. If anyone dares question political liberalism, for example, he is likely to be denounced as a dreaded “Christian nationalist.”

I am personally not a Christian nationalist and support the American cultural and political tradition. In fact, I’ve written explicitly against Christian nationalism multiple times. It is also odd to be promoting something like Christian nationalism at the very time when American Christianity has lost the hold on the culture that would allow such a thing even to be viable. Nevertheless, the American system is not contained in the Bible and should not be treated as sacred, which many seem to do in their attacks on any proposed alternative system.

We also see belief in the liberal consensus in the modern Christian treatment of sin. In effect, sins that the secular world condemns are treated as sinful absolutely, whereas sins the secular world approves of are only sinful therapeutically. By therapeutically, I mean that they are viewed simply as suboptimal choices that are not the best path to personal happiness and human flourishing, as opposed to being evil or offensive to God.

Sexual sin tends today to be treated therapeutically, as being about “brokenness.” Some Christian leaders even “lament” that the Church has been an “unwelcoming” place for “sexual minorities.” Abortion is denounced as murder, yet the official position of leading pro-life organizations is that women who abort their babies are “victims.”

It goes without saying that racism and “Me Too” style sexual harassment are never treated this way. In fact, for the modern American Christian, racism is arguably the unpardonable sin, the only thing that justifies immediately casting someone into the outer darkness. In contrast, being in favor of abortion is merely regrettable, and some Christians will actively applaud, promote, and platform pro-abortion atheists.

I don’t exactly know the right approach to take here myself. Christians shouldn’t ignore racism or refuse to speak to people who support abortion. But there is clearly something very off in the current approach to these things.

One of the virtues of the work of people like Patrick Deneen is a willingness to take a step back and rethink our unreflective religious commitment to what are effectively secular principles of politics and culture. This is not to say, again, that we can turn back the clock to the polity of the Middle Ages. But as we attempt to adjust to life as a minority, we need to understand what our own religion teaches about matters like gender, race, and politics, and seek to apply those teachings to our lives and churches in today’s context.

Principle #4

Do not remain too wedded to the strategies of yesteryear.

I noted above that the ministry and engagement strategies of the American church were created in the positive and neutral worlds and were tuned to the cultural context of those eras. In the Evangelical world, I identify three principal strategies: culture war (or the religious right), seeker sensitivity (often seen in non-denominational megachurches), and cultural engagement (the urban church movement).

Each of these strategies got important things right. The culture warriors understood that sometimes you have to be unpopular with society’s elites. The seeker sensitives did not want to put man-made barriers between people and Christ. The cultural engagers understood the importance of the life of the mind and vocation.

Yet each has elements that no longer work in today’s negative world. For example, the culture war as traditionally understood is obsolete. American Christians are now a moral minority, and their preferences on social issues are unpopular and political losers. This reality has to be confronted and responded to. The cultural engagers lack cultural confidence and too often simply echo the fundamental values of secular society and too seldom challenge them in foundational or unpopular ways. And each of these strategies is starting to become deformed in some ways under the pressures of the negative world.

These strategies need not be seen as failures, or their practitioners as wrong. Rather, the cultural context has changed; thus the way ministry is done must also change. To give one small example: when visiting with the Chicago intentional community Jesus People USA, which grew out of the Jesus Movement, I was told that they used to do a lot of street evangelism but have stopped doing it because it is no longer effective. What are the best ways to do evangelism in today’s world? They might be very different from what worked in times past.

Principle #5

Do think eschatologically.

Eschatology is the theology of the end times. Evangelical churches are often heavily oriented around particular eschatological visions of the future, usually either post-millennialist (the view that the millennial age will be inaugurated on earth before Christ’s return) or dispensational pre-millennialist (associated with the idea of the “rapture”). That’s not what I’m talking about here. In fact, I think there is too much of that kind of eschatology.

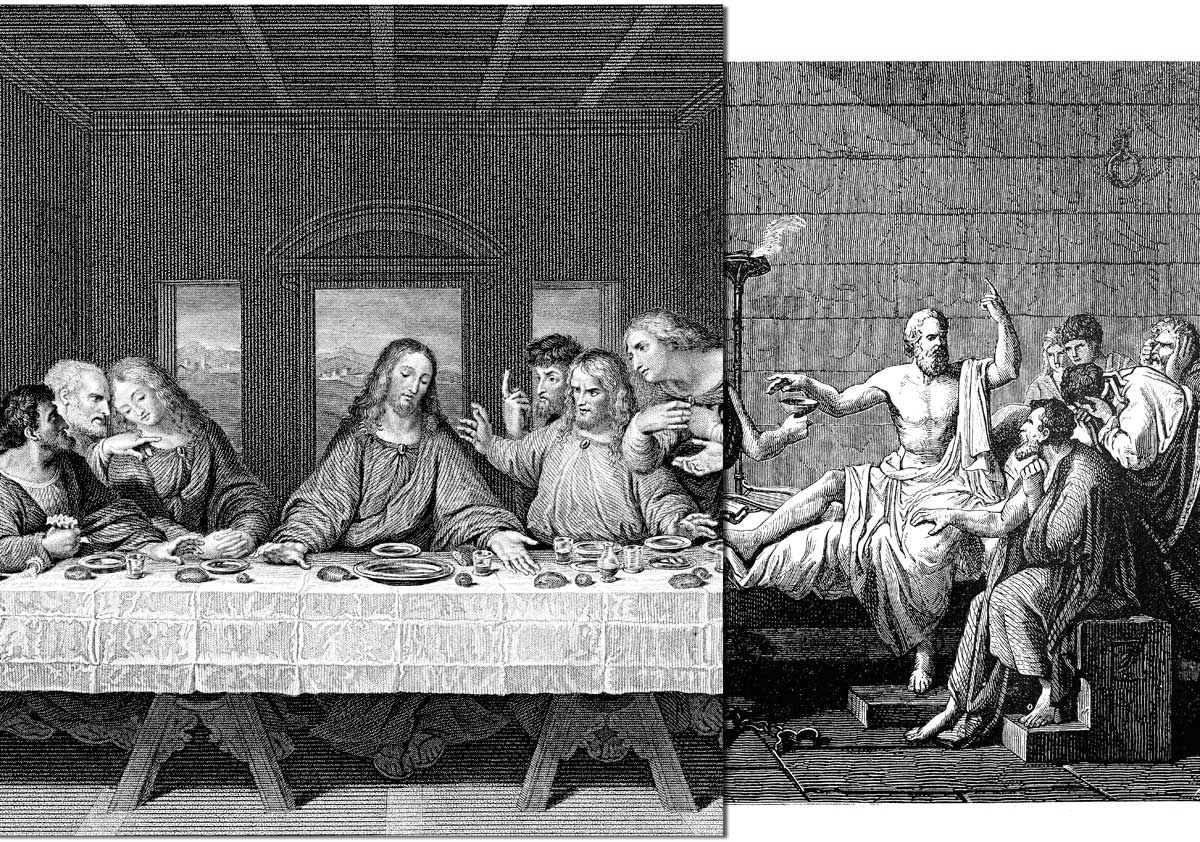

The philosopher Charles Taylor, in his book A Secular Age, describes a secular age as one in which “the eclipse of all goals beyond human flourishing becomes conceivable”—that is, an age in which we lose sight of transcendent value that exists beyond our material existence in this world. But we see in the New Testament that our promised inheritance is in the age to come. Ultimate value is beyond this world. Of course, that does not mean that this life is of no significance. We see how significant it is in many ways, such as in Christ’s healing of the sick and disabled. Still, we are told that our ultimate reward is yet to come.

An eschatological perspective reminds us that we should be storing up treasures for ourselves in heaven, that whatever troubles we experience now are not worthy to be compared with the glory that is to be revealed. It also reminds us that no man knows the day or the hour of Christ’s return, so we should be living our lives prepared at every moment to give an account to him who will judge the quick and the dead.

If this life is all there is for us, if it is all that consumes our minds, then we will never be able to respond faithfully to a negative world.

Principle #6

Do think about the new possibilities opened up by the negative world.

As Christianity slides to minority status and is viewed negatively or skeptically by secular society, we should be attuned to the new possibilities this opens up for the Church.

Back in the 1950s, when people were almost expected to go to church, it followed that there had to be a place for everybody in the church. That is, the church could not be too demanding of its members. When citizenship and church membership overlap in a normative sense, even when only a minority regularly attends church, a sort of least-common-denominator Christianity is almost mandated.

But when Christianity is a dissident choice, one that comes with social stigma and other penalties, a door is opened to the formation of a more robust church community with higher expectations of its members—indeed, such is almost required. We see this in the New Testament church, as illustrated by the numerous commands given by the Apostle Paul in his letters. Sin is treated as a big deal. Unity, forgiveness, and life shared together are imperatives. This is the type of community Rod Dreher calls for in The Benedict Option. Whether one agrees with Dreher’s specific vision or not, the formation of more robust church communities—as concerned with their internal life and health as with the outside world—will compose an important part of an effective negative-world strategy.

Being able to forgo least-common-denominator Christianity is just one of the possibilities that may be opened up by the decline of Christianity in America. We should be attuned to what others there might be.

Principle #7

Do become more culturally confident.

In a Christian society, the success of that society, or the relative status of Christianity within it, can become the measure of people’s identity, of how confident they feel in themselves. The advent of the negative world can easily produce feelings of pessimism, shame, and even despair. It can lead to a loss of cultural confidence in Christianity and even to embarrassment about the faith.

But if Christianity is true, which it is, then we should be supremely confident even in a negative world. Historian Tom Holland, though not a Christian himself, says he wishes modern Christians were more willing to embrace the “weird stuff” of Christianity, for embracing the “weird stuff” is part of what it means to be culturally confident.

We see cultural confidence in Hasidic Jews and among the Amish. They are not afraid to be seen living radically countercultural lives in our world. They also are not motivated by animosity towards other groups. Indeed, they are not especially concerned with what people outside of their communities are doing at all. But they are confident in who they are and aren’t afraid of other people knowing about it.

Few Christians will want to live that counterculturally. But we should be confident enough in Christ to live fully and authentically as Christians. Much of what the world says may hold high status, but just isn’t true. It’s the product of what writer Nassim Taleb calls the “intellectual yet idiot” class. We need not be intimidated into feeling shame over what we believe, so long as it doesn’t devolve into a sort of anti-intellectual fundamentalism.

Hope & Confidence

The switch to the negative world has presented profound challenges to American Christianity. Yet while this may be a new experience for us, it is not new for other Christians around the world, nor has it been for Christians throughout time, many of whom have suffered far more for their faith than any American is likely to. For the most part, American Christians are merely disfavored, not persecuted. Many have found ways to remain firm and thrive in their faith, and their example should give us confidence that with God’s help we can, too.

Christianity is not destined to have a slow-motion going-out-of-business sale in America. It can have a brighter future than many of us think possible, even if it takes beyond the span of our lifetimes to arrive. These guiding principles are not a detailed strategy for getting to that future, but they point us away from futile approaches and towards fertile ground for the exploration and experimentation in which we need to engage to find a path forward.

Aaron Renn is a writer and consultant in Indianapolis and a Senior Fellow at American Reformer and the author of Life in the Negative World: Confronting Challenges in an Anti-Christian Culture (Zondervan Reflective, 2024). This essay is based on his talk at the 2024 Touchstone conference, Life & Death in the Negative World.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on conference talk from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor