The Sacred Cosmos

The World of Matter & Spirit United in Praise of Its Creator

Ever since the landmark 1966 publication of Ian Barbour's Issues in Science and Religion, the modern science-faith dialogue has flourished. The widening range and depth of relevant scholarship, interdisciplinary work, centers for study, and full academic chairs in the field, are evidence of the health and vigor of the program. Nonetheless, the dialogue has remained very much one-sided in the sense that science continues to enjoy the advantage of priority. Science has "slain" its theologians (T. H. Huxley) and issued its challenges. Faith invariably reacts in rearguard defensive maneuvers, trying to explain how we can still think religiously in a scientific world. Theologians and believing scientists first submit to the primacy of science, then labor to escape the implications of its strict materialist presuppositions, which in fact prohibit any meaningful ontological status to religious categories. Religion must always answer to science, but the converse is almost never the case.

Arguably the most fundamental and enduring problem at all levels in the dialogue is the conceptual difficulty in satisfactorily reconciling matter and spirit. Sarah Lane Ritchie has defined this point of contact, the so-called causal joint, as "that theoretical nexus at which a nonphysical God could affect physical processes." It is the problem of divine action in the material creation, and the dualistic context in which it is usually framed makes the resolution of the problem nearly impossible.

Several models have been proposed, historically and recently. Some are analogical (God as artist; or the world as God's body, with divine action comparable to mental activity). Others are more conceptual (dual agency/primary vs. secondary causality; top-down causality; or God as a transmitter of pure information). Some are more explicitly theological (varieties of panentheism, pneumatological animism, God's will as agency, and the role of divine kenosis—self-emptying—allowing an endowed creation to make itself).

And there are new varieties of what amount to God-of-the-gaps arguments, based on "real" uncertainty in nature (God is the manipulator of quantum indeterminacies or chaotic systems). The promise of true quantum uncertainty as the focus of divine action is that God can now at last work providentially without scientific contradiction or miracle. God is effectively relegated to a basement workshop to tinker with a cosmos otherwise fully governed by the laws of physics. There is little discussion of divine sovereignty and omnipotence in the treatises on divine action.

Divine action is scientifically unknowable because science as currently practiced is applied materialism. No transcendent (or immanent) categories are permissible. This was shrewdly, but diplomatically, summarized by biologist Robert Dorit—"The hand of God may indeed be all around us. But it is not the task of science to dust for fingerprints." As long as naturalism is the only accepted causal currency, it is of little use to appeal to initial conditions, endowed potential, fine-tuning, irreducible complexity, and so on as evidence of divine influence. As far as science is concerned, all phenomena (including whatever we might mean by "spirit") and all emergent complexity collapse into particles and energy/quanta (whatever these prove to be), with no metaphysical remainder. Game over.

The functional, ontological gap between matter and spirit cannot mean they are unrelated, but ignoring any possible bonding is the whole point of so-called methodological/causal naturalism—the philosophical foundation of science. Like an experiment in which variables are isolated or eliminated (to simplify a system and render it explicable), real teleological categories were progressively excised from the project of science as material causes were accepted as more intellectually satisfying (see Collingwood's The Idea of Nature). But the motive for attempting some integration of matter and spirit is our present dissatisfaction with the meta-narrative of science—a disenchanted, desacralized, and utterly pointless universe comprised of only brute material phenomena and their interactive contingencies.

It has been said that the success of science is in part a function of its limited scope. Science is incapable of satisfactorily reducing transcendent and immaterial qualities such as beauty, value, and teleological behavior; nor can it account for the necessary exemption of rational thought from its reductionist program. Scientific explanations are therefore too simple, and are also contingent on the non-material values, motives, and agendas of scientists.

This epistemological handicap of science must be articulated and emphasized in the science-faith dialogue. A richer account of the world is clearly necessary. Matter must be understood as more than mere matter, and its qualities and effects as more than accidental, emergent, self-assembled, or epiphenomenal. What is needed in the science-faith dialogue is a recovery of the ancient concept of the sacred. If the cosmos is a creation, it simply must have a sacral aspect at all conceivable levels.

The Logic of the Sacred

The "idea of the holy" was classically illustrated by Rudolf Otto and Mircea Eliade. Sacrality is a universal and foundational concept in all religious belief and practice. A sacramental understanding is one in which otherwise natural phenomena (objects, places, actions, words) "participate in a reality that transcends them." They are endowed with additional meaning and dimension that is inseparable from them. The sacral dimension is a powerful conceptual tool with the potential to integrate material creation and its dynamic processes with divine presence, creative action, and providence. It must be further explored.

The sacred (as with sacrament) is mysterious, but not in the sense of mere ignorance on our part. It is ontological—it cannot be fully comprehended (and must not be rejected on those grounds). When something is sacred, we may say it is holy, sanctified, consecrated, hallowed, set apart, dedicated, etc. Why? Because the sacred thing somehow contains, reveals, or makes present to us some real but non-material (i.e., non-scientific) aspect in such a way as to be at least partly apprehended by our ordinary senses. Sacred things show us spiritual things by means of otherwise natural things. Without ceasing to be "natural" phenomena, sacred objects, places, actions, or words become more than natural. With the sacred, the duality of matter and spirit no longer exists. A sacramental metaphysic is the only conceivable approach to the radical project of integrating scientific knowledge of the world and our experience of it.

Augustine said that when something is sacred, it carries a hidden meaning. And according to Eliade, "A thing becomes sacred in so far as it embodies (that is, reveals) something other than itself." Thus, the sacred is an immaterial aspect or quality, but it must have a material expression—the sacred must be incarnated. The mysterious or hidden aspect of the sacred is the reality that is behind what is immediately perceived by the senses. Sacramentals must not be confused with symbols. Symbols are representative and communicative only, whereas sacramentals participate in that which they signify. In fact, the natural and the spiritual aspects cannot be separated, and (unlike a symbol) the sacred aspect evokes a reverential response from us. Nor is the sacred merely a projection onto phenomena. The sacred aspect is there, and it is experienced or received by the percipient (the numinous experience of Otto).

The Familiar Sacramental Principle

The sacramental principle is enormously helpful because this otherwise religious concept is tacitly presupposed and understood in nearly all human intercourse and can therefore be employed to clarify our understanding of the integration of matter and spirit. Consider these many examples of "sacred" objects, places, actions, and words.

Sacred Objects.Imagine a personal memento, a family heirloom, or a rare family photograph. The object itself may be deteriorating and materially worthless, but to the owner it is a relic of deep personal sentiment and meaning—no mere symbol. An American flag is materially only red, white, and blue fabric, but it is the material focal point of deep patriotic feeling (with reverent customs for its proper handling). Consider the power embodied in a crucifix and the feelings of awe or even dread it may evoke.

The Scriptures are likewise sacramental—materially only a book but containing the very Word of God. The sacramental principle permeates the text. It is explicit in Numbers 16:35–40 (concerning the bronze censers used in Korah's rebellion): "pick up the censers out of the blaze, for they are holy . . . let them be made into hammered plates as a covering for the altar. Because they presented them before the Lord, therefore they are holy." And consider Jesus' words in Matthew 23:17b, 19b: "Which is greater, the gold or the temple that has made the gold sacred? . . . The gift, or the altar that makes the gift sacred?"

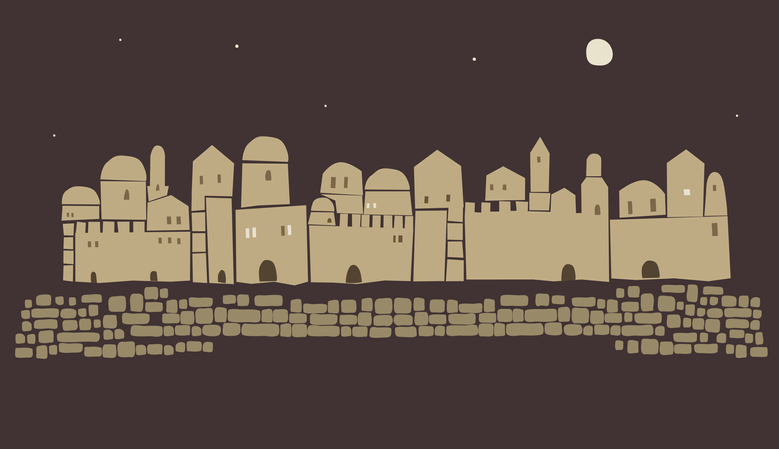

Sacred Places. One's birthplace or hometown carries obvious, personal sacral value. National monuments, cemeteries, and battlefields are similar. Who can stand within the Lincoln Memorial, read his Second Inaugural Address, and not be deeply moved? And special reverence and honor has always been given to holy sites and cities, church sanctuaries, and countless other places of religious significance. Why are places endowed with sacrality? Because events of the greatest and most enduring significance, not to be forgotten, occurred (or are commemorated) there. They occupy "holy ground."

Sacred Actions. The common social convention of shaking hands is a sacramental-like action because it communicates greeting, farewell, promise, congratulations, or other goodwill. Such invisible meanings require a physical action for their expression. A military salute communicates strong, even sacrificial, commitment. The changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (expressly to guard the nation's honor) is entirely a sacramental ritual. And consider baptism—materially just water on the body, but the ancient ritual of initiation is necessary for spiritual commitment, transformation, and growth.

Sacred Words. How absurd the "scientific" proposition that a mother's "I love you" to her child is only the expression of selfish genes. It is, rather, the verbalization of the deepest and most unselfish of sentiments. What about, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal. . . ."Just ink on parchment? No, the Declaration of Independence is a most sacred American document.

Finally, the words of consecration from Jesus: "This is my body. . . . This is my blood. . . ." Is the Eucharist to be regarded as merely bread and inexpensive wine? Or in it, are we not fully united with the body, life, and sacrifice of the Son of God—our "bread of life" and "cup of salvation"? The Eucharist and other sacramentals are vectors of divine grace. They are not magical. They are spiritual transactions.

These examples, secular and religious, are understood as sacred because they are accepted as carriers of real and irreducible truth, meaning, value, beauty, and power. They are manifestations of transcendent realities. Their sacramental hidden meaning cannot be isolated from them—their sacred aspect is a "real presence." The higher truths each embodies and communicates have ontological mass.

It could be said that the sacramental principle is generic and rather easily understood in relational, anthropological contexts (personal, patriotic, religious), as summarized above. Sacrality is acquiredorconferred in most cases and understood in measure or proportion appropriate to each circumstance. But can we probe deeper into the inherent and indelible sacrality of creatures (created things), which variously reveal the invisible attributes of their Creator (Rom. 1:20)?

The Logoi of Beings

The Eastern Church fathers long ago developed a compelling insight into the sacrality of created things. It is the concept of logoi of beings. Logoi are uncreated, divine ideas, reasons, intentions, purposes, qualities, and energies that eternally reside in the transcendent Logos but are variously incarnated in the multiplicity of created things. Often translated "inner essences" (as in The Philokalia), logoi are the archetypes of order and purpose in all creatures, seen and unseen. Rooted in Platonism to be sure, the concept of logoi in creation has obvious biblical valence, and its development was a powerful theological accomplishment in the hands of Origen, Dionysius, Maximus, and others.

The rationale of uncreated logoi forever residing in, but also emanating from, the eternal Logos, dynamically and clearly manifested in innumerable created forms (John 1:3; Rom. 1:20) yet perpetually "held together" (Heb. 1:3; Col. 1:17; Acts 17:28) and ultimately "gathered together" (Eph. 1:10) by the same Divine Logos, is a compelling vision of the nature of created things. The logoi of beings seem to imply far more than mere architectural- or engineering-like ideas and designs. Logoi have sacramental grist—creatures are composed of eternal and uncreated qualities. Their "inner essences" are vital and dynamic, ever moving with teleological inertia, and manifesting their borrowed glory.

This resonates with common language in the Psalms, in which created things (the heavens, fields, flocks, trees, mountains, sea animals, storms, and so on) naturally "praise" their Creator (Ps. 19:1-4; 65:9-13; 96:11-12; 97:1-6; 145:10-11; 148). Without a deep sacramental understanding, the language of mountains singing and trees clapping their hands (Is. 55:12) ceases to be even metaphorical.

Can we speculate as to what this might look like in practice? What if we began the project of some exploratory work in recognizing, naming, and contemplating possible logoi of beings? What properties, qualities, energies, relations, and interactions in created things might conceivably constitute logoi?

We would presumably want to start with fundamental particles, the creation of which we suspect occurred by condensation from the energy of an unimaginable (and inexplicable) primordial event. Material existence itself must be understood as a logos, a good derived from the eternally existent Logos, and so declared in Genesis 1. But existence is not passive. The creation of heavy elements within stars (especially the effectively miraculous requirements for the nucleosynthesis of carbon), along with the seeming unlimited creative potential and internal energy with which they are endowed, is a profound density of creative power concentrated in the very least of creatures perceptible to us.

The precision and sensitivity ("fine-tuning") of fundamental physical parameters in the universe (e.g., the expansion rate, gravitational force, strong nuclear force) testify of an astounding and unlikely order. That such a stable universe would emerge out of an event like the Big Bang is nearly unbelievable. Suspicion is warranted. The universe seems "balanced on a knife edge" (Barbour), is understandably suspected as being "monkeyed with" (Hoyle), and its origin admittedly has "religious implications" (Hawking).

It is intellectually dishonest to dismiss these conditions as mere artifacts. In fact, this so-called anthropic structure of the universe is a primary motivation for the proposal of a multiverse. So we are expected to believe that our universe simply must hold the winning ticket in a multi-cosmic lottery with regard to initial conditions (the Big Bang had to be a very precise event), physical constants, raw materials, and other truly countless "lucky" circumstances, allowing it to evolve into a stable, fertile, multipotent cosmos, ecologically habitable by intelligent observers. While a multiverse is conceivable on other grounds, it would not change the obvious—the contingent glory of God declared by the heavens (Ps. 19:1–4; 97:6).

Similarly, the numerous, "Goldilocks-like" circumstances of the Earth in the Solar System (e.g., planetary size, distance from the Sun), and the Gaia-like (i.e., self-regulating) dynamics of the Earth, all make Earth a supreme and exclusive planetary habitat for life. How lucky are we? Very! Just look at Mercury, Venus, Mars (and the Moon)—all "fossil" planets, preserved in various dead-end states of planetary evolution. The more obvious question is, "Are we more than lucky?" Even with the discovery of many other potentially habitable, Earth-like exoplanets, the "just right" circumstances necessary for our existence on Earth require thoughtful consideration not constrained by materialist presuppositions.

Surely the actualized mathematical relations and symmetry in nature, which underlie all quantification in science, reflect a divine aesthetic and order. Crystallographic systems, body plans (phyla), protistan and molluscan shells, and galaxies are obvious examples. The teleological implications of coded genetic information, reproduction, adaptability, evolution, co-evolution, convergence, and the ecological interdependence of species should be freely discussed. The biosphere is far more complex than any non-living system, and natural selection acting on random mutations alone is starting to look impossibly simplistic (see work in the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis).

Further, life is not merely going along for the ride on spaceship Earth, but continuously contributes to the construction, maintenance, and functional unity of all the interacting systems of the geosphere (viz., lithosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, biosphere). Teleological qualities and behaviors need to regain ontological traction.

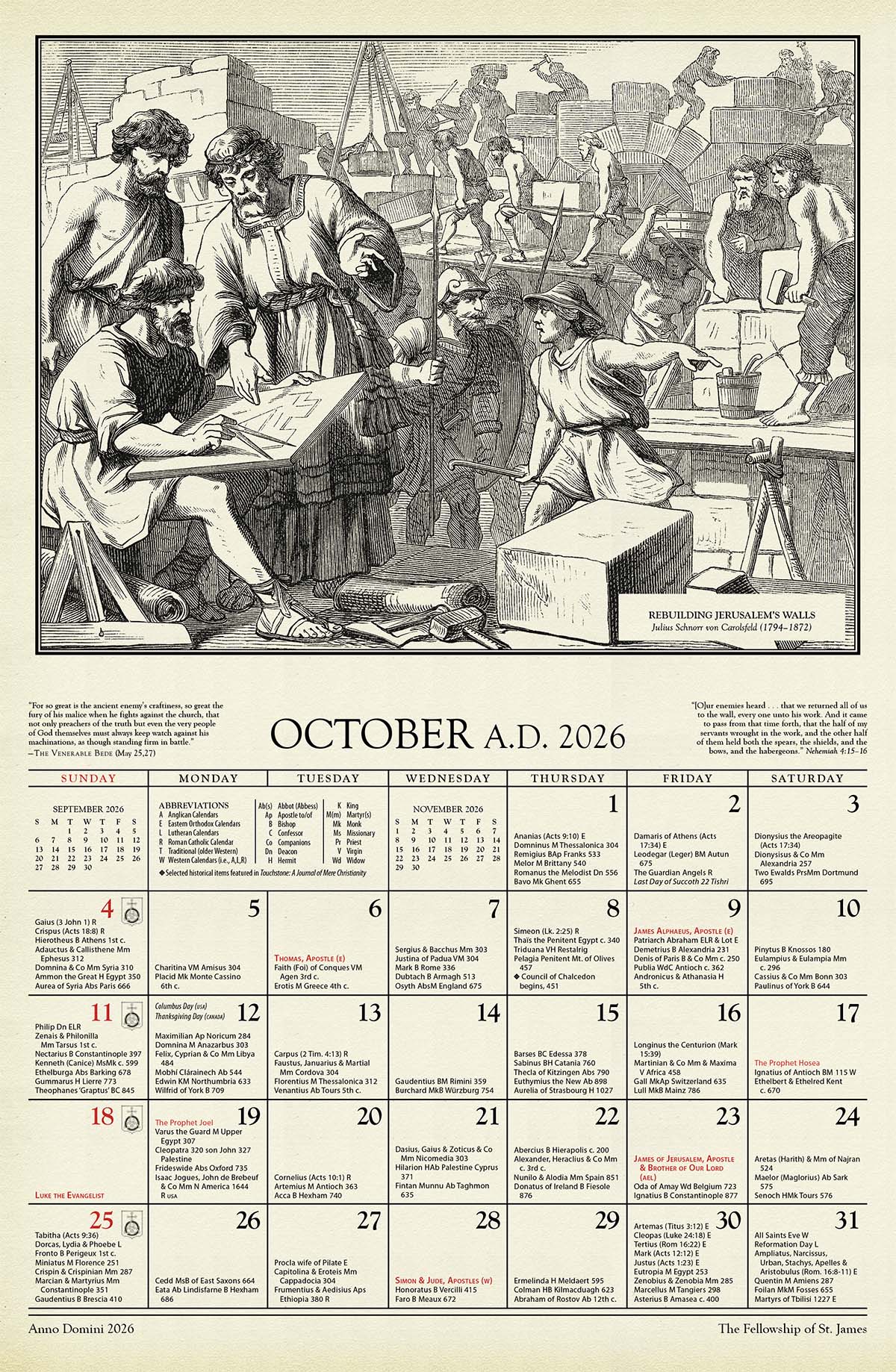

There are many explicit biblical sacral associations that should be explored in the context of the Logos-logoi

relation, including the imago Dei in humans and the relation of the Spirit (Heb. Ruach) with wind, breath, word, and life (Gen. 1:2; 2:7; Ps. 33:6; Job 33:4; 34:14–15; cf. 12:10; 27:3; 32:8; Is. 42:5). As the Psalmist beautifully declares, "The voice of the Lord maketh the hinds to calve" (Ps. 29:9a). And there is the deep redemptive significance of the fact that "the life is in the blood" (Gen. 9:4; Lev. 17:11–14; Heb. 9:12).

The Cruciform Fabric of Creation

A sacramental understanding of creation may also be of special assistance in the "problem of pain," at least with regard to suffering, death, and extinction in the non-human biosphere. It has been suggested by many that nature exhibits a "cruciform pattern." Holmes Rolston discusses the cruciform character of nature within the "whole of earthen metabolism." Life is a "passion play"—a tragic, sacrificial struggle for life. But it is a redemptive suffering—life is worth it. The cruciform struggle has its archetype in the suffering God: "seen in the paradigm of the cross, God too suffers, not less than his creatures, in order to gain for his creatures a more abundant life." Rolston concludes, "The way of nature is the way of the cross; via naturae est via crucis."

The cruciform concept is clearly a sacramental theological proposition and an explicit teaching of Christ (John 12:24–25, Mark 8:34b–35, etc.), but it is equally an ecological principle and could even be stated as a scientific law. Life comes at an almost prohibitively high cost. The Cruciform Fabric of Creation is the biological and spiritual necessity of sacrificial death for the sustenance of all life. This is evident at every level of the ecosphere and may even be extended to the larger cosmos with the requisite "death" of stars for the creation of the elements of life.

Darwin might have us believe that the drive for survival lies behind the cruciform pattern in nature, and so it is, at least in part. But this does not subtract from the sacral meaning of sacrificial death. Likewise, altruism in insect colonies, birds, and mammals may (or may not) be explained in terms of reproductive fitness, but it does not cease to have sacral significance.

A "New Natural Philosophy"

The sacramental principle weds matter and meaning, natural process and divine action, and adorns the cosmos with authentic beauty, value, and destiny. The logoi of beings provide further insight into this fundamentally mysterious bond. According to Eastern Orthodox divines, however, the perception, understanding, and contemplation of the "inner essences" (logoi) of creatures are not simply matters of scientific observation. They require rigorous spiritual discipline, devotion, and the practice of Christian virtues, with even monastic fortitude. If this is so, perhaps our proposed project will have minimal success. One can only hope that some progress is possible by devout divine-image bearers. We may have a very long way to go. But the possibility of a glimpse of the "cosmic liturgy" of the Creator is an exhilarating prospect.

Throughout his career, C. S. Lewis sustained an unrelenting critique of materialism/ scientism. In The Discarded Image, he lamented the need for a new model of the world. The science behind the medieval cosmos certainly proved wrong, but the sacral, poetic beauty and wonder of the previous worldview were discarded with the science. So far, nothing has replaced them. Writes Lewis:

As long as this deliberate refusal to understand things from above, even where such understanding is possible, continues, it is idle to talk of any final victory over materialism. The critique of every experience from below, the voluntary ignoring of meaning and concentration on fact, will always have the same plausibility. There will always be evidence, and every month fresh evidence, to show that religion is only psychological, justice only self-protection, politics only economics, love only lust, and thought itself only cerebral biochemistry.

In The Abolition of Man, Lewis hints at what a revised science, a "new Natural Philosophy" might look

like:

When it explained it would not explain away. When it spoke of the parts it would remember the whole. While studying the It it would not lose . . . the Thou-situation. . . . Its followers would not be free with the words only and merely. . . . The whole point of seeing through something is to see something through it.

This would be very close to a science that was conditioned to consider the sacrality of its subject, but it would certainly not be science as presently understood and practiced. It would also not, technically, be a form of natural theology, seeking proofs of God in nature. It would most likely be an entirely new undertaking, contemplating perceived logoi in creation with humility and reverence, ultimately in support of worship. Two collects from the Book of Common Prayer seem to perfectly express the scope and motive for this proposed work:

For Knowledge of God's Creation

Almighty and everlasting God, who made the universe with all its marvelous order, its atoms, worlds, and galaxies, and the infinite complexity of living creatures: Grant that, as we probe the mysteries of your creation, we may come to know you more truly, and more surely fulfill our role in your eternal purpose; in the name of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

For Joy in God's Creation

O heavenly Father, who has filled the world with beauty: Open our eyes to behold your gracious hand in all your works; that, rejoicing in your whole creation, we may learn to serve you with gladness; for the sake of him through whom all things were made, your Son Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The first man named God's creatures (Gen. 2:19–20), and Solomon "spoke of trees, from the cedar tree of Lebanon even to the hyssop that springs out of the wall; he spoke also of animals, of birds, of creeping things, and of fish" (1 Kgs. 4:33). Many early scientists saw the design and sacrality of the cosmos. Some responded in outbursts of praise (e.g., Kepler). But there has long been a disconnect, leaving us with, at best, an incomprehensible, dualistic universe. We need to give it another try. If an inconspicuous wildflower is more endowed than all the glory of Solomon's kingdom (Matt. 6:28–29), then we have much to contemplate indeed (Ps. 139:17–18).

Jonathan R. Bryan , Ph.D., is a Professor of Geology and Oceanography at Northwest Florida State College, and a vocational deacon at Immanuel Anglican Church, Destin, Florida. An early award winner in the Templeton Foundation Science & Religion Course Program, he developed and taught Issues in Science & Religion at NWFSC for 15 years. He is the senior author of Roadside Geology of Florida and a licensed professional geologist in Florida.

Share this article with non-subscribers:

https://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=35-04-030-f&readcode=10806

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on science from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor