2017 Conference Talk

The Garland of Immortality

A Theology of Martyrdom in the Early Church

by Bryan A. Stewart

Around the year a.d. 155, the 86-year-old bishop of Smyrna, named Polycarp, was arrested by Roman authorities. The charge leveled against him was that he was a Christian. On his way to the arena, some individuals tried to persuade the aged Polycarp to save his life by recanting his faith and making sacrifice to the pagan gods. “What harm is there,” the police captain argued, “for you to say, ‘Caesar is Lord,’ to perform the sacrifices . . . and thus save your life?” Polycarp refused.

Later, having arrived in the arena, the proconsul took a different approach to persuade the bishop to recant. “Have respect for your age,” he argued; “swear by the genius [spirit] of Caesar and recant. . . . Swear [the oath of allegiance] and I will let you go. Curse Christ!” Again, Polycarp refused, this time with the famous words, “For eighty-six years I have been his servant, and he has done me no wrong. How can I blaspheme my King who saved me?” Polycarp would stand upon the simple, but clear, confession: “I am a Christian.”

That trial ended with Polycarp being first burned and then stabbed to death before a crowd of onlookers. The document that recounts his death, The Martyrdom of Polycarp (hereafter MP, contained in The Acts of the Christian Martyrs [hereafter ACM], ed. Herbert Musurillo [Clarendon Press, 1972]), is one of the earliest martyrdom accounts we have from the first three centuries of the Church. It would by no means be the last. Because of their consistent refusal to offer pagan sacrifice—an act Christians understood as idolatry—thousands of Christians in the Roman Empire would come to know the fate of Polycarp only too well. Until the peace of Constantine in the early fourth century, arrest, mistreatment, persecution, and execution for being a Christian was a true possibility, and many thousands would come to know it as a reality. This was, in the words of scholar William H. C. Frend, “the heroic age of the church” (Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church [New York Univ. Press, 1967], ix).

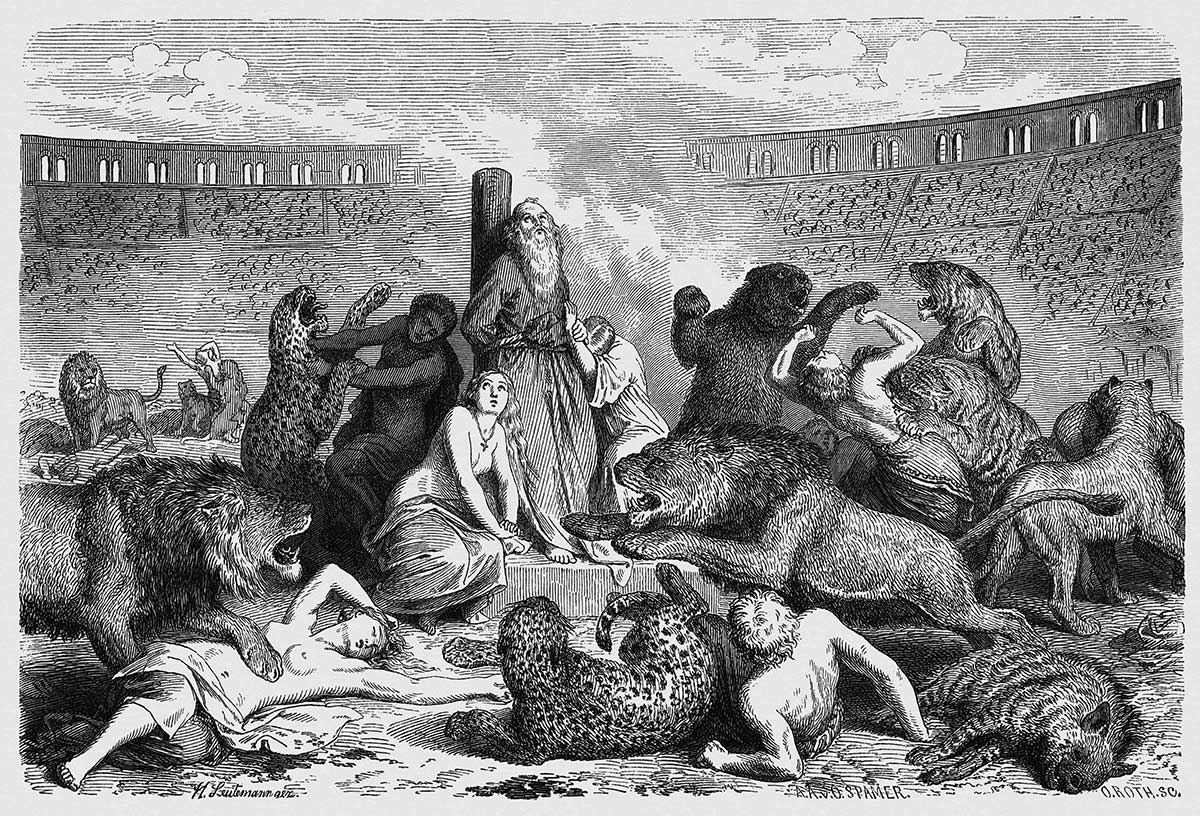

These persecutions gave rise to a new kind of Christian literature: trial records and passion narratives recounting the episodes of persecution. Such documents often contained graphic details of the cruelties and tortures Christians endured at the harsh hands of Roman soldiers and magistrates, which included being burned alive, stabbed, and thrown to wild beasts to be torn apart by tooth and claw. Eusebius of Caesarea, a fourth-century bishop and historian, describes Christians being subjected to hot iron placed on sensitive parts of their bodies, boiling water and molten lead being poured upon their naked flesh, their limbs being ripped apart, and their skin being flayed with sharp instruments of clay and metal (Eusebius, Church History VIII.9, 12).

The early Christian martyrdom accounts are no sweet bedtime stories. Yet for all their gruesome details, we know that they were intended to give encouragement and inspiration to living Christians; indeed, they were often circulated among churches and read aloud in public liturgies. Moreover, these Christian deaths were considered to be nothing short of—in the words of the account of Polycarp—“martyrdoms in accord with the pattern of the gospel of Christ” (MP 19.1).

What, we might ask, did it mean for Christians of the time to write and circulate records of the trials, persecution, and (often brutal) deaths of their fellow brothers and sisters, and in what way did they consider them to be “in accord with the pattern of the gospel”? Or, to put the question more simply: What was the theology of martyrdom in the early Church?

We might begin to answer that question by looking into what the word “martyr” means. Ask people today and most of them will say something like: “A martyr is someone who dies for his faith or who is killed for what he believes in.” While this is true, of course, of the early Christian martyrs, it does not capture the full meaning of the ancient texts, because it leaves out the original meaning of the Greek word martyr, which is “witness.”

When early Christians reflected on the deaths of their fellow believers at the hands of the Romans, and when they began to write about them, the word they intentionally (and consistently) chose for them was martyr, “witness.” In their deaths, these Christians became witnesses to other believers and to the world; in particular, they became “witnesses” of the pattern of the gospel itself. I would like to highlight four distinct yet related aspects of the theology of martyrdom as “witness” in the early Church.

A Spiritual Battle

First, martyrdom was understood as witnessing to the real spiritual and cosmic battle taking place in the hidden realms. Early Christian literature repeatedly refers to Christian martyrs as “noble athletes” who are fighting, not against Roman soldiers or wild beasts, but against the dark forces of Satan. This theme of spiritual battle is not subtle. One account describes a martyrdom in second-century Gaul as “the Adversary swooping down with full force” (The Martyrs of Lyons [hereafter ML] 1.5, in ACM). A third-century text from North Africa explains that “the onslaughts of persecution surged like the waves of this world, and the fury of the ravening Devil gaped with hungry jaws to weaken the faith of the just” (The Martyrdom of Saints Marian and James 2, in ACM).

Bryan A. Stewart is Professor of Religion at McMurry University in Abilene, Texas, where he teaches the history of Christianity. In addition to scholarly articles and essays, he has published a monograph entitled Priests of My People: Levitical Paradigms for Early Christian Ministers (Peter Lang, 2015), and has a volume coming out in March in The Church's Bible series: The Gospel of John: Interpreted by Early Christian and Medieval Commentators (Eerdmans). An ordained Anglican priest in the traditional Diocese of Fort Worth (ACNA), he serves as the vicar of Holy Cross Anglican in Abilene.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on martyrdom from the online archives

more from the online archives

28.3—May/June 2015

Of Bicycles, Sex, & Natural Law

Describing Human Ends & Our Limitations Is Neither Futile Nor Unloving by R. V. Young

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor