Russian Orthodoxy

Encountering the Church Unknown

by Heinrich Stammler

It might strike you as odd, even paradoxical, when I designate the Russian Orthodox church as the Church Unknown at a moment in its history so fraught with significance and glory. The millennium of Christianity among the Eastern Slavs (the nations which we now call Great Russians, Byelorussians, and Ukrainians) has become a prominent topic in our press, not only in religious and scholarly books and periodicals, but also in the secular newspapers, journals, magazines and, of course, television. All these factors contribute to make this branch of Christendom better known in the minds of the people. Let us hope that these endeavors will prevent the Orthodox church from sinking again into oblivion.

Perhaps this danger can best be illustrated anecdotally. In 1925 the first ecumenical congress took place in Stockholm, inspired by the benevolent guidance of Sweden’s great churchman, Bishop Nathan Söderblom, whose mind and soul comprehended and embraced the entire Christendom in the spirit of charity, understanding, and forgiveness. Here, perhaps, for the first time in modern history since the Reformation, the Eastern Orthodox church became visible before the eyes of the world in the person of a number of hierarchs, bishops, and abbots, who took an active part in the deliberations. I still vividly remember the wonder with which the presence of these Eastern churchmen was noticed, surrounded as they then were by the halo of martyrdom, persecution, and enforced exile. It was as if one had encountered the body of one who had long lain in the grave and was now miraculously resurrected.

Another story, of a more humorous character, is lifted from the midst of everyday life. In the thirties there flourished in the city of Florence in Italy a small Orthodox parish mainly composed of Russian emigrés. They were spiritually nourished and guided by their pastor—let us call him Father Innocent—a typical old-style Russian batiushka (the classical Russian parish priest) of the best sort, good-natured, devout, kindly and outgoing, a thoroughly lovable man and priest. One day Fr. Innocent had to make a trip to Milan by rail. The train was crowded, and he found himself squeezed into a corner of the compartment with half a dozen or more Italian travellers. And since he was wearing his full clericals with pectoral cross, long hair and beard, he aroused much curiosity on the part of the other passengers. Amused, he observed how they were nearly bursting with desire to learn what sort of parroco (parish priest) this peculiar fellow might be. Finally, one of the fellow-travellers took his heart in both hands, daring to make the pertinent inquiries. Fr. Innocent, who spoke fluent Italian, tried to explain that he was a priest of the Eastern Orthodox church. And when his comments met with incomprehension, he added a few elucidating observations of a partly historical character, making mention of the Byzantine background of the Eastern Orthodox church and the ecumenical patriarchate in Constantinople. And here, all of a sudden, it was as if his inquirer saw daylight, and he jubiliantly exclaimed, “Ah, now I see: You are a servant of the Prophet!”1

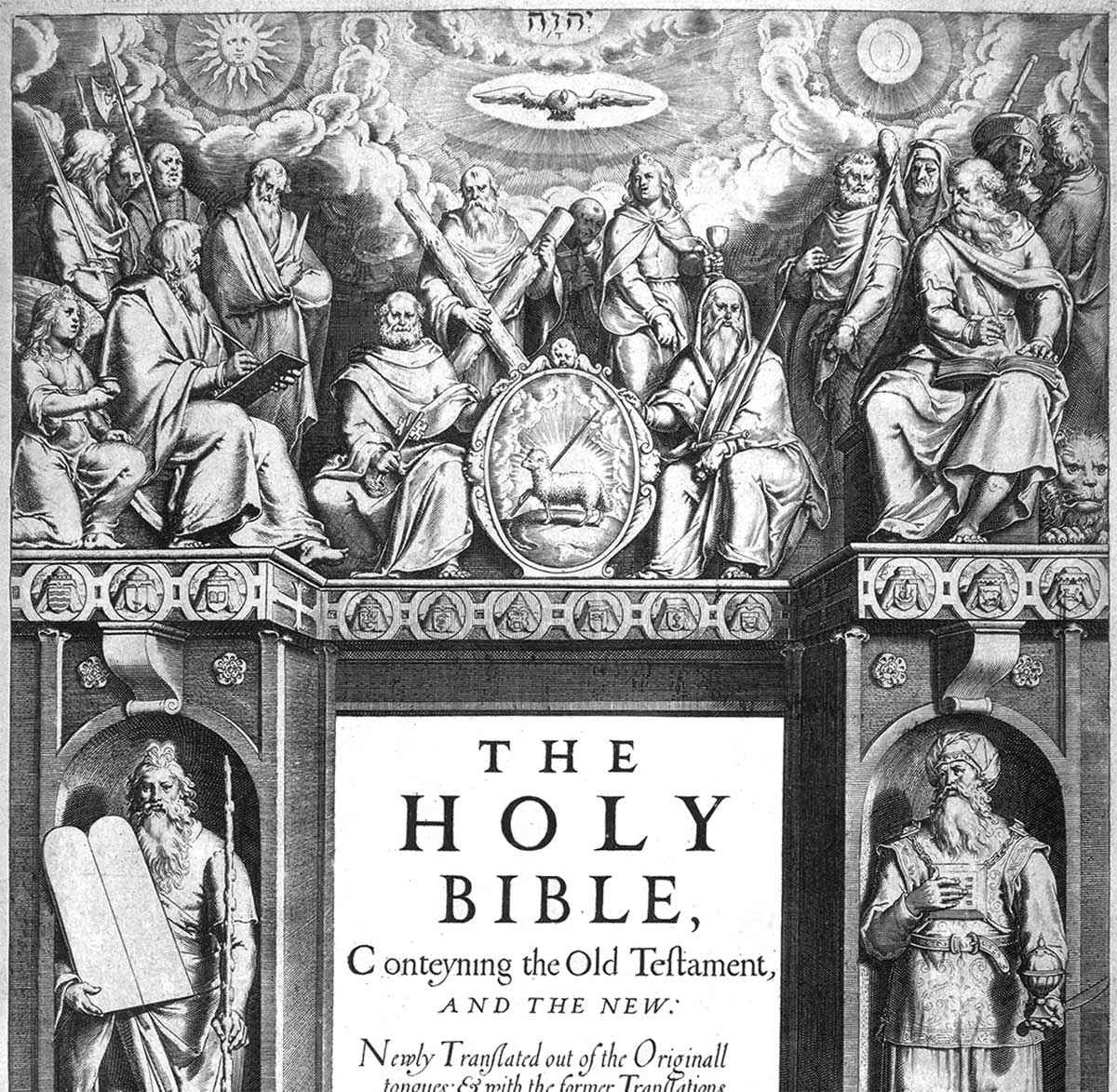

A third example comes from the area of Western theological studies. Some years ago I was a visiting professor at a private university of great distinction and an excellent reputation, not least because of its internationally known Protestant divinity school. One day I paid a visit to this renowned school’s no less renowned library. I found holdings and collections of truly staggering dimensions. It goes without saying that the wide field of Protestant theology was very well represented. But also Roman Catholicism was not neglected, and the same can be said about the many evangelical and other free churches and sects. Likewise, the sections devoted to Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism could be regarded as thoroughly respectable. Also a great number of works dealing with pagan cults in various parts of the world were made available. What was, however, virtually absent was a section reserved for Eastern Orthodoxy and other Eastern churches. The beholder could not but receive the impression that Islam and Hinduism are incomparably nearer to the religious and theological consciousness of Western Christianity. Hence the expression, “The Church Unknown.”

This abyss of oblivion is the product of an estrangement—deep and longstanding. Several factors coincided so as to produce this dividing line between the Christian East and the Christian West, a line which almost down to our own times has seemed ineradicable. These factors are of a most various nature: historical, moral, cultural, geopolitical, and geographical. But only a few of the most significant and consequential events and circumstances can be touched upon here.

First of all, I must mention the Crusades—a sequence of campaigns, missionary activities, new international and economic contacts, but also of brutal conquests, fratricidal warfare and intrigue—in short, an epic, a chanson de geste with all the heroic and brilliant, but also the somber and cruel aspects of such a saga.

Shortly before the First Crusade, the final rupture between Rome and Constantinople occurred. The fateful incident of the pope in Rome and the patriarch in Constantinople mutually excommunicating one another happened in the year 1054. But given the means of communication of those times, it took a long time before an awareness of the fact trickled down to the masses of believers. One hundred and fifty years had to elapse before a disaster happened which made it clear to those in the remotest corners of the Russian north—the sack of Constantinople by the crusaders and Venetians in the year 1204. What followed was the partition of the once powerful Byzantine Empire and the establishment of Latin rule, all of which was impregnated by an attitude of hostility, contempt, and, at best, condescension toward the Eastern Orthodox church and her communicants.

Even before 1204, however, many frictions had arisen between Western knights and Byzantine generals and courtiers. These were not only the result of considerable differences in political and religious objectives, but also acute cultural contrasts between the Latin West and the Greek East. Whoever wants to inform himself about these conflicts is advised to read the Alexiad, written by the remarkable Byzantine “great lady” and historian, Anna Komnena. It is devoted to the glorification of the great deeds performed by her father, the Emperor Alexis I. The deep distrust between the chivalrous, but also rough, uncouth, and rapacious Latin warriors and the highly polished, sophisticated Byzantines becomes more and more evident as the reader progresses from page to page. Then, in the year 1204, the powder keg exploded. The East Roman Empire was destroyed and was never fully to recover from this blow. And the entire Christian East felt that the Latins attacking Constantinople instead of fighting the infidels had committed the crime of stabbing their Christian brethren in the back—a crime which down to our own time still lingers in the historical memory of the Christian East.

Another cataclysmic event which contributed to remove the Russian lands from Western vision was the Mongol conquest about the middle of the thirteenth century. It destroyed the Kievan political system, decimated and impoverished the population, sowed the germs for the later split up of the Eastern Slavs into Great Russians, Little Russians or Ukrainians, and Byelorussians, and, finally, placed the remaining Russian principalities under Tartar or Mongol overlordship. This meant that the conquered land had simply become a province and administrative district or ulus, as the Tartar word goes, of the vast empire founded by Ghengis Khan. While the kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania carried forward their own expansion into the geopolitical vacuum left by the Tartar inroads, the Swedes and the Teutonic Knights in the North also tried to profit from the troubles and the turmoil of the Russian lands.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Orthodox from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor