On Our Faces

A Faithful Church Is a Trembling Church

Scripture speaks plainly: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” (Prov. 9:10). What happens, then, when this fear is lost?

The modern Church—especially in the West—has become strikingly casual about holy things. Preaching is often an exercise in motivational speaking. Prayer is flippant, the Name of God taken lightly, and the moral authority of Scripture often subject to the approval of the zeitgeist. The Church still speaks of grace but forgets that grace comes to the humble—and humility, true humility, begins with fear. Not the fear of punishment, but the trembling awe of standing before the Holy One of Israel.

This is not a call for emotionalism or reactionary aestheticism. It is a call to remember what the Church is and whom she serves. It is a call to let the Church tremble again.

Fear as Foundation

At the heart of biblical religion lies a trembling awe before the presence of the Almighty. From Genesis to Revelation, the testimony is consistent: the fear of the Lord is not an archaic relic of an earlier, more superstitious time; it is the foundational posture of the faithful.

Proverbs declares it plainly: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge” (1:7). In this short axiom, wisdom is not first intellectual, nor is it moral in the purely humanistic sense. It is theological. Wisdom begins when man stands rightly before God—humbled, aware of his own sin, and conscious of God’s majesty and holiness. To fear God is to see things as they truly are.

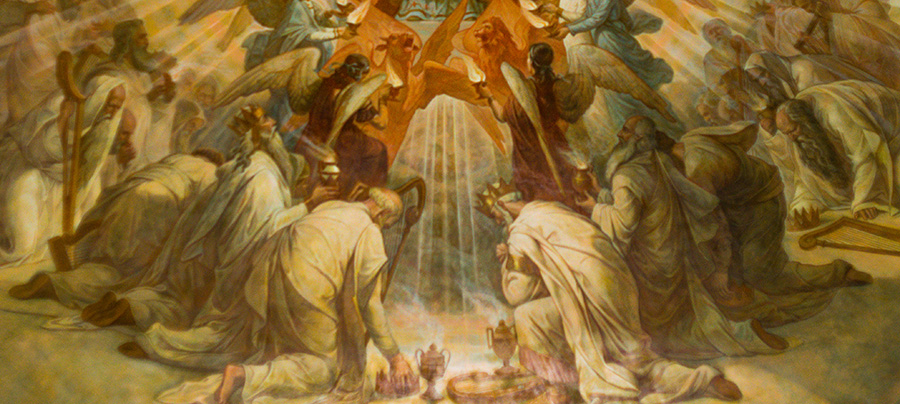

Consider Isaiah. When he beholds the Lord “high and lifted up,” his response is not applause or affirmation—it is dread: “Woe is me! For I am undone . . . for mine eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts” (Is. 6:5). The prophet’s lips are purified only after his trembling confession of unworthiness. This sequence is not incidental but paradigmatic. Revelation follows reverence. Forgiveness follows fear.

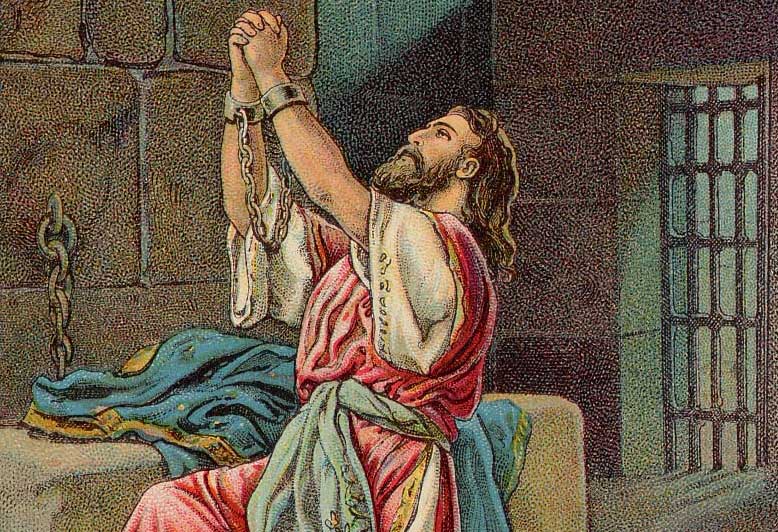

Likewise, the New Testament does not set aside the fear of the Lord as something obsolete. After the terrifying judgment of Ananias and Sapphira in Acts 5, we are told, “So great fear came upon all the church and upon all who heard these things” (5:11). This is not pre-Pentecostal fear; it is fear within the born-again, Spirit-filled Church. And the result? “And through the hands of the apostles many signs and wonders were done” (5:12). Fear did not quench the Spirit—it made room for him.

The epistle to the Hebrews reminds its readers that even under the New Covenant, “our God is a consuming fire” (12:29). Far from relaxing the standards of holiness, the new and living way opened by Christ demands a deeper awe. We are not invited to come with informality, but “with reverence and godly fear” (Heb. 12:28). This fear is not servile dread, like a slave before a cruel master, but filial awe—a child before a father whose glory burns brighter than the sun.

This distinction is vital. Christian fear is not the paralyzing terror that flees from God but the purifying awe that draws near on holy ground. The great Reformed theologian John Murray put it succinctly: “The fear of God is the soul of godliness.” The Church must recover this soul or risk losing her very life.

Even Jesus, in his humanity, “offered up prayers and supplications, with vehement cries and tears . . . and was heard because of his godly fear” (Heb. 5:7). If the Son of God feared rightly, how much more must we?

But today, we are taught to cast out fear entirely. Preachers, eager to comfort, quote 1 John 4:18: “Perfect love casts out fear.” But they forget the context: the fear cast out is the fear of judgment for those perfected in love—not the reverent fear that leads to holiness. Love does not eliminate awe; it completes it. The redeemed still fall on their faces in the presence of the Lamb (Rev. 5:14).

In Scripture, to fear God is not to flee from him, but to flee from everything that would dishonor him. It is to live under his gaze, conscious of his holiness, mindful of his justice, grateful for his mercy. The fear of the Lord is not the enemy of love; it is its beginning.

A Historical Witness

The Church was not born in comfort. It emerged in an upper room, behind closed doors, in prayerful waiting and trembling expectation. When Ananias and Sapphira lied to the Holy Spirit and fell dead, the text does not record outrage or confusion. It records awe: “Great fear came upon all the church.”

Where the Spirit moved, so did holy fear. Scripture reports that the early Christians “continued steadfastly in the apostles’ doctrine and fellowship, in the breaking of bread, and in prayers. . . . Then fear came upon every soul” (Acts 2:42–43).

As the Church spread, the fathers of the Church, whether Latin or Greek, testified to a Christianity steeped in reverence. St. John Chrysostom, preaching in Constantinople in the fourth century, lamented the casual attitude of some communicants. “When you see the Lord sacrificed and laid upon the altar,” he thundered, “do you then dare to send forth your unclean soul?” He called the faithful to weep, to tremble, to recognize the awesome mystery before them.

Likewise, Cyril of Jerusalem, in his Mystagogical Catecheses, instructed the newly baptized to approach the mysteries “not with your wrists extended, nor with your fingers spread, but making your left hand a throne for your right, which is to receive so great a King.” This was not ceremony for ceremony’s sake. It was the embodied language of fear and love, an expression of the trembling reverence appropriate to divine encounter.

The Reformation, though often caricatured as stripping away mystery, was rooted in fear—a holy fear of divine justice and the terror of sin. Martin Luther, tormented by the wrath of God and the weight of his own unworthiness, rediscovered the righteousness of Christ not through lightheartedness but through dread and trembling. He did not flee fear; he sought a refuge that could withstand it.

The Puritans, often maligned for their sternness, nevertheless understood that to enter into covenant with God is no casual matter. Jonathan Edwards’s famous sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” may offend modern ears, but it moved men to repentance.

Even the Evangelical revivals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—Wesleyan, Whitefieldian, Finneyite—testify to this sacred fear. Men cried out under the weight of conviction. Camp meetings were not platforms for lighthearted banter but places where sinners collapsed in the dirt, crying for mercy. Hymns spoke of awe: “Let all mortal flesh keep silence,” “Were you there when they crucified my Lord?”, “Amazing grace, that saved a wretch like me.”

The fear of the Lord, properly preached, did not drive men away; it drove them to their knees—and then lifted them in joy. Revival was not excitement without fear, but fear transformed into obedience, gratitude, and holy living.

This legacy of reverence formed the Christian imagination for centuries. It shaped prayer, worship, preaching, and art. And where it was present, the Church was strong—not necessarily socially powerful, but spiritually potent. She stood before the world not as a mirror of it but as a sign that Another had drawn near.

How Reverence Was Lost

The decline of reverence in the modern Church did not occur overnight. It has been a slow erosion, subtle at first, then obvious—like a cathedral gutted from within while its facade remains intact. What we are witnessing now is not merely the absence of solemnity but the triumph of a different spirit: one of casualness, comfort, and entertainment.

The first tremors came in the Enlightenment, when man began to enthrone reason over revelation. The God of fire and glory became the god of the philosophers—distant, abstract, deistic. The fear of the Lord was now seen as primitive, even unbecoming for enlightened people. Faith was domesticated. Churches began to reflect the lecture hall more than the temple. God was no longer the consuming fire of Sinai, but a one-time creator on whose work men could make progress.

Reverence took a far more severe blow in the twentieth century, with the triumph of psychology and the culture of self-esteem. Church became a place not to tremble, but to “feel good.” Preachers were no longer prophets or theologians but therapists, coaches, or motivational speakers. The cross was still present, but its message was re-branded—not as the place where divine justice and mercy met in terrifying splendor, but a symbol to which men might turn to fill a missing void in their lives.

Secular culture taught people to seek comfort, not truth; affirmation, not transformation. Tragically, much of the Church followed suit. We traded confessionals for counseling centers, altars for stages, and prophets for performers. The gospel became a product marketed to religious consumers, and reverence was recast as rigidity.

Perhaps no movement better illustrates this shift than the seeker-sensitive trend of the late twentieth century. Born of good intentions—to reach the unchurched and make Christianity “relevant”—it nevertheless led to the remodeling of churches into auditoriums, pulpits into plexiglass stands, and hymns into pop songs.

Liturgy, if it existed, was truncated. Silence was eliminated. The sacred was redefined as “authentic,” which often meant spontaneous, casual, and unscripted. Clergy exchanged vestments for jeans, and branding teams replaced altar guilds. A God who inspires trembling was no longer marketable.

This was not merely a change in aesthetic. It was a change in anthropology and theology. The unspoken message became clear: God is our friend, not our judge; worship is for us, not for him; and nothing about his presence should make us uncomfortable. But Scripture testifies to the opposite. In God’s presence, men fall down. Priests are struck dead for strange fire. Isaiah is undone. John, the beloved disciple, falls as though dead before the risen Christ.

Contributing to the hollowing has been the collapse of catechesis. Where the fear of the Lord is not taught, it cannot be retained. Generations have now come of age in the Church without any deep exposure to doctrine, biblical history, or liturgical meaning. The average churchgoer in the West is more likely to know the lyrics to a praise song than the Ten Commandments. Reverence cannot flourish in a vacuum of knowledge.

The sacred becomes profane when it is no longer understood. Without teaching on holiness, sin, sacrifice, judgment, and the awe-inspiring nature of God, reverence is unintelligible. It becomes a quirk of older generations or a “high church thing,” rather than the lifeblood of worship.

The Path of Recovery

If the Church is to rise again in power, she must first kneel in fear. Reverence must be rebuilt in doctrine, worship, and discipleship. Each requires careful attention—and the courage to repent.

Recovery of Doctrine: The holiness of God is not one attribute among many—it is the radiance of all his perfections. To say God is holy is to say he is utterly set apart: in power, in purity, in majesty. “Who among the gods is like you, O Lord? Who is like you—majestic in holiness, awesome in glory, working wonders?” (Ex. 15:11). That holiness is not diminished in Christ; it is revealed more clearly.

In many churches today, God is spoken of casually. But casual speech leads to careless thought, and careless thought to corrupted worship. Theology that lacks the fear of the Lord becomes human-centered, therapeutic, and ultimately impotent. If God is not feared, he will not be obeyed, and if he is not obeyed, he will not be known.

Let the Church return to her creeds, her catechisms, her Scriptures. Let her teach again the terrible mercy of the cross—the wrath of God borne by the Son of God, that sinners might be reconciled. Until the congregation hears that God is not safe, they will never know that he is good.

Recovery of Worship: Worship is the soul’s answer to the reality of God. When the Lord is trivialized, worship becomes entertainment. When he is rightly known, worship becomes reverent joy.

The Church must restore worship that reflects the weight of divine presence. This does not mean every church must adopt a high liturgy, but it does mean that worship must be ordered, intentional, and God-directed. The aim is not aesthetic taste, but theological integrity. Liturgical form is not merely tradition—it is catechesis in action. Reverent prayer, sacred music, Scripture reading, confession, silence, and sacramental attention all teach the heart to bow.

The loss of sacred space must be addressed as well. We do not worship architecture, but our bodies and minds are shaped by place. A sanctuary should look and feel different from a shopping mall or a theater. It should whisper, even before a word is spoken: “Take off your shoes. This is holy ground.”

And the sacraments must again be treated as holy mysteries, not religious props. Baptism must be taught as death and resurrection, not as ritual decor. The Eucharist must be revered as communion with the crucified and risen Lord—not taken lightly, and never without discernment. “He who eats and drinks in an unworthy manner,” warns Paul, “eats and drinks judgment to himself” (1 Cor. 11:29).

Recovery of Discipleship: The fear of the Lord begins in worship but is sustained in life. A Church that trembles on Sunday must walk humbly on Monday. Discipleship, rightly understood, is the cultivation of holy fear in every area of life.

It demands discipline. The fear of the Lord is not a passing feeling but a formed habit. Prayer, fasting, Scripture reading, confession, and Christian fellowship are not spiritual accessories; they are the ordinary means by which the soul is trained to live under God’s gaze. Without them, reverence fades.

It begins with repentance. The Church cannot tremble before God if she is winking at sin. We must recover the language and practice of repentance, both individually and corporately. Our worship will regain weight when our hearts regain contrition.

The path of recovery is not quick and will not win the applause of the world. But it is the only path to renewal. A Church that fears the Lord will be hated by some, but she will be filled with glory. Better a trembling Church than a dead one.

The Fruits of Holy Fear

The fear of the Lord is not a spiritual detour but the straight path to life. The wisdom literature of Scripture makes this plain: “The fear of the Lord is a fountain of life, to turn one away from the snares of death” (Prov. 14:27). It is not repression but release, not bondage but blessing. To fear God rightly is to be made whole.

Modern ears recoil at the word “fear” because we associate it with trauma, abuse, or control. But Scripture speaks of a different kind of fear, one that produces joy, obedience, and renewal. A trembling Church is not a weak Church; it is a holy Church. And from holiness comes strength.

Let us consider some of the fruits of holy fear.

Fear Protects Against Apostasy. Where there is no fear of God, there is no seriousness about sin. And where sin is taken lightly, heresy and apostasy are never far behind.

Many denominations have capitulated to the spirit of the age, not because they were intellectually convinced but because they no longer feared disobedience and so lost discernment. Once the idea of divine judgment is domesticated, the Church becomes its own authority. Scripture is reinterpreted to fit the times, and doctrine becomes elastic.

In an age of moral ambiguity, when even many churches cannot define marriage, sex, or sin, the loss of wisdom in the absence of fear is evident. A Church that does not fear the Lord cannot think clearly. She is tossed by every cultural wind, driven by sentiment rather than Scripture.

Holy fear guards the deposit of faith. It says with Paul, “I charge you before God and the Lord Jesus Christ . . . preach the word!” (2 Tim. 4:1–2). It sees false teaching not as a curiosity to be tolerated, but as a cancer to be cut out. Without fear, correction is offensive. With fear, correction is love.

Fear Cultivates Holiness. Holiness does not come naturally to fallen men. It must be pursued.

Paul says, “Let us cleanse ourselves from all filthiness of the flesh and spirit, perfecting holiness in the fear of God” (2 Cor. 7:1). Holiness is not moralism; rather, it is the fruit of a life lived under the weight of divine glory. It is born not of pride but of trembling love.

When the Church fears the Lord, she repents quickly, forgives deeply, and resists the world’s charms. She disciplines her members not out of cruelty but care. And she teaches her children not merely to believe but also to obey.

A generation raised in holy fear will not be swayed by TikTok theologians or celebrity apostates. They will stand, because they have knelt.

Fear Produces Joy and Assurance. Paradoxically, the fear of the Lord leads to joy. Psalm 112 says, “Blessed is the man who fears the Lord, who delights greatly in his commandments.” In God’s economy, reverence and rejoicing are not opposites; they are companions.

This is because fear drives out presumption and breeds humility. And where humility reigns, grace abounds. The fearful heart is tender to the Spirit, eager for Christ, and ready for glory. It is not afraid of God’s wrath, because it rests in his mercy. But it never treats that mercy lightly.

True assurance is not bravado; it is reverent trust. The soul that trembles before God’s holiness clings more tightly to the cross. It rejoices in justification, not because it denies judgment, but because it sees what judgment cost.

Fear Strengthens Witness. In an age of glib certainties and manufactured spirituality, the Church that trembles stands out. Her worship is weighty. Her preaching is bold. Her members are set apart.

Peter exhorts the faithful, “Sanctify the Lord God in your hearts, and always be ready to give a defense . . . with meekness and fear” (1 Pet. 3:15). Evangelism rooted in fear is not anxious, but it is serious. It knows what is at stake. It does not shrink from the cost of discipleship, because it has already counted the cost of sin.

The Church that fears the Lord is not silent in the public square, nor is she shrill. She is solemn. She speaks not with arrogance, but with gravity. She calls men not to a lifestyle, but to their Lord.

The fruit of fear is sweet, though it grows from bitter soil. It begins with awe, moves through repentance, and blossoms into joy. Without fear, the Church is noisy but ineffective. With fear, she is quiet, but her words carry weight. “Blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord. . . . Behold, the eye of the Lord is on those who fear him, on those who hope in his mercy” (Ps. 33:12,18).

A Call to Kneel

In the Book of Revelation, the Apostle John is caught up into heaven. There, before the throne of God, he sees what so few see on earth: a Church that trembles rightly. The twenty-four elders fall down. The living creatures cry “Holy, holy, holy.” The redeemed cast their crowns at the feet of the Lamb. There is no chatter, no casualness, no distraction—only awe. And from that awe flows unceasing praise.

This is not a vision for another time. It is the pattern for ours.

We must recover the fear of the Lord—not as a passing mood or emotional moment, but as a way of life. Pastors must preach with weight. Worship leaders must remember the presence they lead others into. Parents must teach their children not just to believe in God, but to stand in awe of him. Churches must shape their spaces, their liturgies, their calendars, and their habits around the unshakable holiness of God.

Let the Church tremble again—and she will stand again. Not because she has regained cultural power but because she has remembered her purpose: to glorify the God who dwells in unapproachable light, and yet draws near in grace.

A trembling Church is not a fearful Church. It is a faithful one. And in the days to come, it may be the only Church left standing.

Ronald Moore is the pastor of St. Luke’s Church in Corinth, Mississippi. He writes on Christian doctrine, church history, and the renewal of reverent worship in the modern Church.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor