Open Our Eyes

on a Vaccine for the Pandemic of Lunacy

The craziness of the culture has become so obvious that, finally, everyone gets it. We don’t need to go into the details of tampon dispensers in boys’ bathrooms.

And yet I don’t think most of us realize just how far the lunacy has gone. Consider the social media remark, “Math is actually not universal. Treating it as such upholds white supremacy.” It’s easy to laugh, but the author of the tweet is a math teacher, and this sort of thing is actually taught in some public schools. Or consider the tweet: “2+2 in #Theology can make 5. Because it has to do with #God and real #life of #people.” This was posted by theologian and Pope Francis confidant Antonio Spadaro, who was defending certain statements against critics who had pointed out that they contradicted the moral doctrine of the Catholic Church.

We are told that basic right and wrong are vague, equivocal, and different for everyone. That sometimes we just have to do the wrong thing. That good character is unnecessary for well-being—or even that there is no such thing as good character, that everyone merely responds to the incentives presented to him.

And on and on and on.

The difficulty of doing something about such exotic ideas is that they aren’t just the fancies of our managerial and opinion-forming classes. Ordinary people who decry the lunacy of our times often accept humdrum versions of the same delusions, even while denying their implications. We want lunatic premises without lunatic conclusions. We want the poison apple without the worm. I notice, for example, that moderates and conservatives who protest lunatic versions of “marriage” such as polyamory quite often believe that cohabitation without vows and with freedom to change partners is equivalent to marriage. Again, moderates and conservatives who would consider it totalitarian to forbid women to stay at home to raise their children commonly view women who do choose that way of life as dim bulbs.

In a word, the reason insanity makes way so rapidly is that the knife of the premises has already been slipped quietly between our ribs—and we have slipped it there ourselves. And this is why, even though many of the outré symptoms that ordinary people find so ridiculous, offensive, or baffling will eventually fade, the underlying fallacies are likely to outlive them and produce new symptoms, perhaps equally outré. All too often what we mean in calling ourselves “conservative” is that although we complain about new craziness, we want to conserve the craziness we have swallowed already.

Defensive Postures

Like most of us, I would prefer to see our culture not destroyed, but renewed and revitalized. If we are serious about this hope, we must be brutally honest, because rejuvenation requires so much intellectual revision, so many changes in our lives, and so much contrition, that, over time, our resistance to doing what has to be done becomes greater and greater.

To justify doing nothing, we adopt various defensive postures. Postures like what? One is simple incredulity: This can’t be happening. Things look okay in my little niche. Another is shooting the messenger: If you think things are as crazy as all that, you must be very disturbed. Perhaps we are amused: All this is just a silly season.

Aversion is one: All the stuff going on is too creepy to pay attention to. Boredom is another: Who cares—it’s not a real issue like war or the economy. There is also obliviousness: Whatever is happening, it couldn’t affect me or my kids.

Then comes cynicism, the view that it’s only politics as usual, followed by mockery: That’s just a conspiracy theory;bylegalism: All we need to do is pass a few more laws;by fear: I can’t speak up because I don’t want to lose my friends or my job;and by conformity: I can’t bear to think differently from the people in my milieu. These postures are followed by complacency: After all, people always say the old days were better;and distraction: I have plenty of other more important things to worry about.

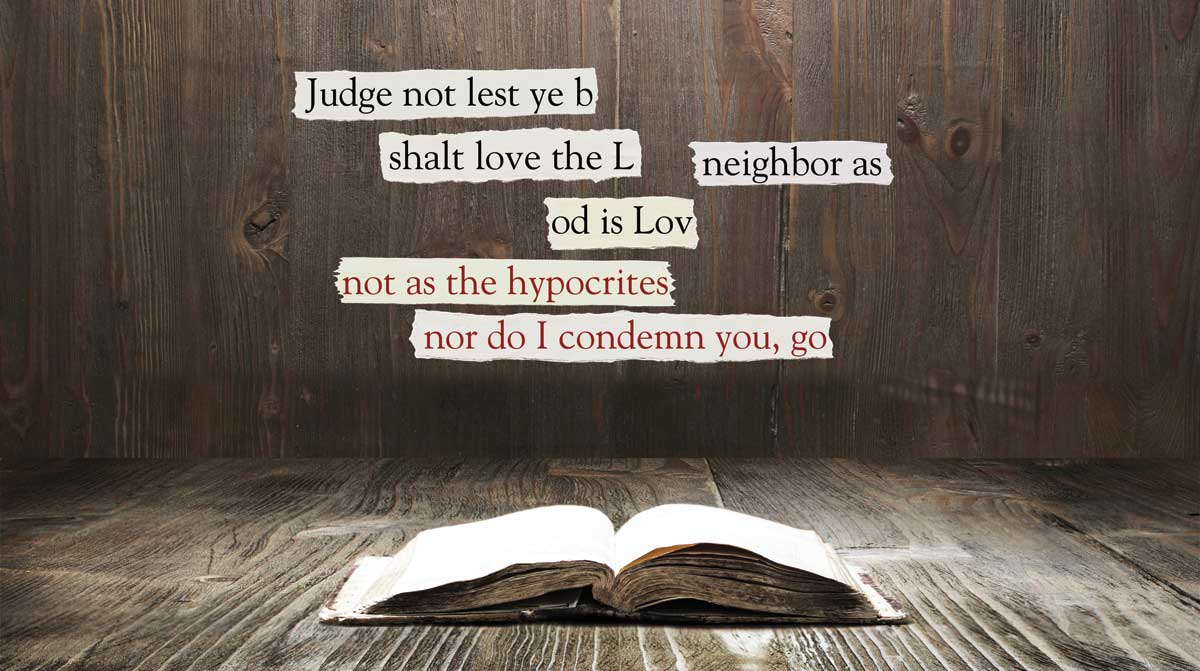

Some people, stupefied, say, I can’t take in the enormity of what is happening. Others, despairing, mourn that everything is inevitable, and I’m on the wrong side of history. Still others, perhaps ashamed of themselves, ask, Who am I to judge anyone or anything? Hypocrites reassure themselves: The crazy people are bad, I’m good, and nothing else matters. People who just want to be left alone dismissively say, I don’t care what happens as long as it isn’t shoved in my face.

And finally, some just capitulate: As Alexander Pope wrote, “Vice is a monster of so frightful mien, / As, to be hated, needs but to be seen; / Yet seen too oft, familiar with her face, / We first endure, then pity, then embrace.”

And there is a lot of embracing going on.

Three Phases of Thinking

When I wrote my new book Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy, a sane friend wondered whether perhaps the only ones who would consider the case against lunacy might be those who don’t need to hear it. I am a little more upbeat. True, our arguments on behalf of sanity may not be very helpful to those who are most deeply ensnared. But I would like to think they may be helpful to those of us who are merely troubled and confused; to those who are in twilight, wondering whether the world is going crazy or they are; to those who have touched the snare but are not yet ensnared; and to those who are beginning to consider getting loose. There are a lot more of those than you might think.

In fact, there is a lot that we can do—although my thinking about what we can do has changed quite a bit over the years. In fact, it has gone through three phases.

In the first phase, I thought, as most academics do, that all mental confusion is innocent error, so that all we need to do is make better arguments than deceived people do. If someone said to me, “Isn’t morality relative?”, I thought I had to convince him that murder is really wrong. If I pointed out an incoherency in his argument and he replied, “That’s okay, the universe is incoherent anyway, and I don’t need meaning and truth,” I thought I had to convince him that the universe isn’t incoherent, and that he did need meaning and truth.

The problem with that approach is that you can’t convince people of what they already know but deny. So in the second phase, I confronted them directly. If someone said, “How do we even know that murder is wrong?” I now asked, “At this moment, are you in any real doubt about that?” If he replied, “Some people might say it’s okay,” I now pointed out, “I’m not asking some people. I’m asking you. Are you in any real doubt about murder being wrong?” The fellow would usually admit that he wasn’t.

Similarly, if someone said, “The universe is incoherent, and I don’t need meaning and truth,” I now said, “I don’t believe you. You know as well as I do that the longing for meaning and truth is deep-set in every mind. So the real question is this: What is it that is so important to you that you are willing to give up even meaning and truth to have it?” And for a little while, the fellow would be baffled and have nothing to say.

But this approach had a problem, too. As I said, the fellow would have nothing to say for a little while. After a minute or two he would get back in the groove of clever chattering.

It seemed to me, and it still seems to me, that we have the stronger position. The longing for truth, for purity, for lightness is indestructible. But I didn’t take sufficient account of the fact that the fear of truth, of purity, and of lightness is also very strong. In the first place, these three things make demands on us: they call on us to change. In the second place, they lead to God, and we are terrified of him, because he desires our good so much more than we do. O God, give me those goods you desire for me, even those I am not yet able to desire, and that I would tremble to conceive!

So in the third phase I have changed my thinking yet again. I used to repeat St. Thomas Aquinas’s formula that our nature is a praeambula fidei, a preamble to faith—and I still do. But now I realize that this proverb tells only half the story. In an odd sort of way, faith may sometimes be a praeambula amicitiae cum natura, a preamble to friendship with our own nature. By grace, our hearts are no longer riddled with desires that oppose their deepest longings, and we no longer demand to have happiness on terms that make happiness impossible. We no longer suffer the urge to resist good arguments.

What We Can Do

And yet moral and cultural apologetics, as I attempt in my new book, are not the same as evangelization. At best, they can whet the desire for that which the gospel shows us how to reach. So again—short of saving grace, but perhaps anticipating it—what can we do?

We can open our own eyes. I think that’s a lot. So many of us have been frightened into thinking that “history,” meaning the last fifteen minutes, “is against us.” But God is for us, his providence is for us, his image in us is for us, and the last fifteen minutes don’t matter.

We can counteract the appeal to inappropriate feelings by appealing to appropriate feelings. So often we say “No” to such things as sexual disorder by pointing out the misery they cause, yet we say far less than we might about the goodness of family and the exuberant joy of happy marriage.

We can meet lunacies not just with counterarguments, but with sounder, more beautiful visions of how things really are. Just having the courage to describe these beauties can be transformative. It can even happen that, at last, at very last, the longing for beauty overcomes the fear of it.

We can cooperate with the restorative tendencies of our nature, including our longing for the truth of things, and with the grace that supports these restorative tendencies, even short of redemption. Consider friendship. Often jealous, even cruel, yet friendship as such is good and to be affirmed. Even in a social media world, people still long for it, though they know less and less about how to have it.

Here is a hard one: we can repent. Those three words are enough to move some people to throw away this essay. I hope they won’t.

But isn’t it good to know that we can turn away from lunacy? Nothing requires deluded thinking. We are not in chains. And if there is such a thing as God, there is such a thing as grace.

J. Budziszewski is Professor of Government, Philosophy, and Civic Leadership at the University of Texas at Austin, and the author of several books, including Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy (Creed & Culture, 2026).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor