The Urgency of Wonder

Re-enchanted Christianity as a Negative World Survival Skill

by Rod Dreher

The word “enchantment” is annoying and twee. It brings to mind a vision of Disney magic, of sparkles, glitter, sugarplum fairies, and the aroma of chocolate chip cookies baking in grandmother’s oven. Unfortunately, it is the word sociologist Max Weber used to identify the “disenchanted” way we all live in the post-Enlightenment world.

So when I argue that re-enchantment is a necessary survival skill for Christians in the “negative world,” as Aaron Renn calls contemporary culture, with its anti-Christian fundamentalism, it’s important to clarify that I’m not urging readers to bring smells, bells, and a faith-friendly version of New Age woo into their religious lives. No, what I mean by enchantment is something far more substantial. In fact, because it has to do with the metaphysical reality of how we live, and move, and have our being, it’s the most real thing there is.

What is Christian enchantment? In the disenchanted world, there is no transcendental or spiritual dimension to existence. Matter is dead. Science and other forms of empiricism are the only reliable ways to know truth. There is no fundamental and objective significance, no logos, embedded in anything. Meaning is what we impose on a meaningless world. Miracles don’t happen. Religion is at worst a harmful delusion, and at best a socially beneficial mythology, but it certainly has nothing to do with truth.

Most people don’t live that way, of course, but this is the framework we are given for understanding life in the modern West. A surprising number of Christians in the West have unthinkingly accepted many of its premises. How many Christians have come to believe that matter doesn’t really matter, that faith is about studying Scripture, affirming certain propositional truths, going to church on Sunday, and being a good neighbor? Yes, the Christian life does entail those things, but that’s not the whole of it.

An American exchange student approached me in Hungary last year and, referring to his Evangelical faith, said, “I believe it all, but I’m dying to experience transcendence. What should I do?”

He is a believer, so not entirely disenchanted. But he sensed that he was missing some fundamental dimension of the Christian experience. As he struggled to explain himself, I heard in his words a sense of longing and disappointment that he might have put in the form of a question: Is this all there is?

No, I told him; this is not all there is. In subsequent conversations (for we have become good friends), I told him about the Anglican theologian Hans Boersma’s concept of “sacramental ontology”—that is, the idea that the things we experience with our senses are connected in a mysterious but real sense to God. We live not in a meaningless universe, but in an ordered cosmos.

All of material creation is shot through with logos, or rational purpose. If we see the world as it truly is, we will understand it as a mystery through which God discloses himself—in other words, as a sacrament. This is not just a pleasant concept; it describes an actual, existing reality. To be fully human, as God has created us to be, is to participate in that reality, and to be changed by it, to become more holy and conformed to Christ. Our role is a priestly one: to be instruments of the Holy Spirit for the transformation and sanctification of the world.

All things, therefore, are sacred, and must be treated as such. Nothing is meaningless. Truth is objective, but the truth of the things that really matter can only be known subjectively—that is, through the individual person grasping it with passionate inwardness, and allowing it to make of him a new creature in Christ.

This, I explained, is what it means to be re-enchanted as a Christian. I told him about Hans Boersma’s concept of the Great Tradition—the Christianity of the first millennium, when all believers shared a sacramental ontology. The good news is that we Christians all shared that in the past and might recover it today. The even better news is that disenchantment is primarily a phenomenon of the contemporary West. This means that our disenchanted, or semi-disenchanted, worldview is only that: a temporally and culturally determined worldview, a take.

Though we today plainly see things far more clearly in terms of science, for example, what assurance do we have that we have not achieved that clarity by blinding ourselves in other ways? Yuval Noah Harari says that in the early modern period, we in the West made a fateful choice: to exchange meaning for power. That is, if we denied the sacramentalism and idealism that had been our cultural understanding and instead began to regard the natural world as mere matter, as nothing but stuff, then we could do whatever we liked with it.

The psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist describes this process as deliberately favoring the left-brain way of knowing—the logical, the mathematical, the abstract—over the right-brain way of knowing, which is intuitive, noetic, and subjective. The results have been spectacular in terms of advancing our power over the material world through science and technology, and in making us very rich. But we are spiritually atrophying and losing our will to live. McGilchrist says that a healthy human mind draws on both ways of knowing, but we in the West have stranded ourselves in the left brain—and if we stay there, we will cut off access to the way back.

I told this young man that his hunger for enchanted experience in Christianity was valid, and that older forms of the faith not only explain why but also offer practical spiritual disciplines for opening oneself up to it. Christian enchantment, though, must never serve as a goal in itself, or as any kind of substitute for the difficult and sometimes dull daily work of prayer, repentance, self-discipline, charity, and obedience. If we’re not careful, we will end up chasing experiences as an easy stand-in for the pursuit of the Holy Spirit.

Truths Lost Sight Of

All this was a lot for the young Evangelical student to take in. His particular form of Protestant theology had not given him this conceptual framework. But I don’t wish to be hard on him as an Evangelical. Most of the Catholic and Orthodox Christians I know don’t live by it either. They take in the disenchantment as given, simply because they have been raised in a culture that doesn’t believe what our sacramental traditions teach. If we really believed those traditions, we would be living very different lives.

We know from sociologist Christian Smith’s work on what he calls “moralistic therapeutic deism” that the Christianity of most young Americans amounts to thinking that God wants us to be happy and to be nice to others—and that’s about it. It’s not only young Americans either. I grew up with this kind of thing in the 1970s. It was always a bad idea, but now, in the negative world, it is going to get a lot of people spiritually killed. And many of us older Christians don’t even understand what’s happening right beneath our noses.

Again, let me clarify what I mean by re-enchanted Christianity. At a theological level, I mean we need to return to the sacramental ontology of the church of the Great Tradition. That is, we need to accept that matter matters, and live like it.

What does that signify? That in some mysterious way, the world of spirit and the world of matter interpenetrate. Therefore, the way we pray, worship, eat, make love, celebrate—it all has ultimate meaning. We need to take up spiritual disciplines that draw us closer to the experience of the Holy Spirit, ways of praying and worshiping that take our sacred story and, in Paul Connerton’s memorable phrase, “sediment it into our bones.”

We also need to get it straight in our heads that we are all engaged in unseen warfare with the demonic world; we are in a spiritual battle that is going to intensify as our culture de-Christianizes. You might not be interested in the demons, but they are very much interested in you.

All of this has always been true, though, again, in modern times we have lost sight of these truths, even within Christian traditions. Why is it so urgent that we rediscover them now? Opening oneself to Christian re-enchantment might make for a more interesting and satisfying way of journeying through life, but why is it a matter of survival?

It is to that question that we now turn.

We Are Losing the Young

If we don’t pass the fire of Christian faith down to our children, Christianity will cease to exist. Among younger Americans—the generation of my children—Christianity is in steep decline, not only in terms of raw numbers, but in the quality of the faith.

Sociologist Christian Smith, arguably the top expert on the religious practices of American youth, reported some years ago his finding that most American young adults who profess Christianity have no substantive idea of what Christianity teaches or requires of them. To call them nominal is generous. When I asked Smith how we can retain the young and draw back those who have fallen away, he said he did not know but that it won’t happen through moralism. By that I understood him to mean the standard apologetic approaches that worked on generations past.

The young are seeking re-enchantment—but they’re not looking for it in church, perhaps because they have the sense that they won’t find it there. That was me in 1984: I was an agnostic seventeen-year-old who had given up on Christianity because I thought it was about nothing more than middle-class morality, social conformity, and TV preachers. Then, as part of a tour group, I stumbled into the Chartres cathedral and was overwhelmed by the presence of God in all that medieval beauty. What kind of Christianity could raise up such a temple to God’s worship? I walked out of there touched by enchantment and taking my first steps toward surrender to Christ.

The apologetics came later. But first, the wonder.

Two years ago, a 27-year-old Evangelical Anglican seminarian approached me at an Oxford seminar about enchantment. He told me that my generation likes to think the contemporary church’s greatest challenge is the New Atheism. Not anymore, he said; New Atheism is dead in his generation. But so is Christianity.

What is taking its place? Various forms of the occult. He told me that before entering seminary, he worked in a London advertising firm where, apart from him, everyone was involved with the occult at some level—including two people who were open Satanists. They described Satanism to their co-workers as learning how to live your humanity to the fullest. The seminarian told me that he knows he will be dealing with this dark enchantment among his generation for the rest of his ministry. He offered me this warning as a wake-up call for us older members of the church, who aren’t in a position to see what’s happening now.

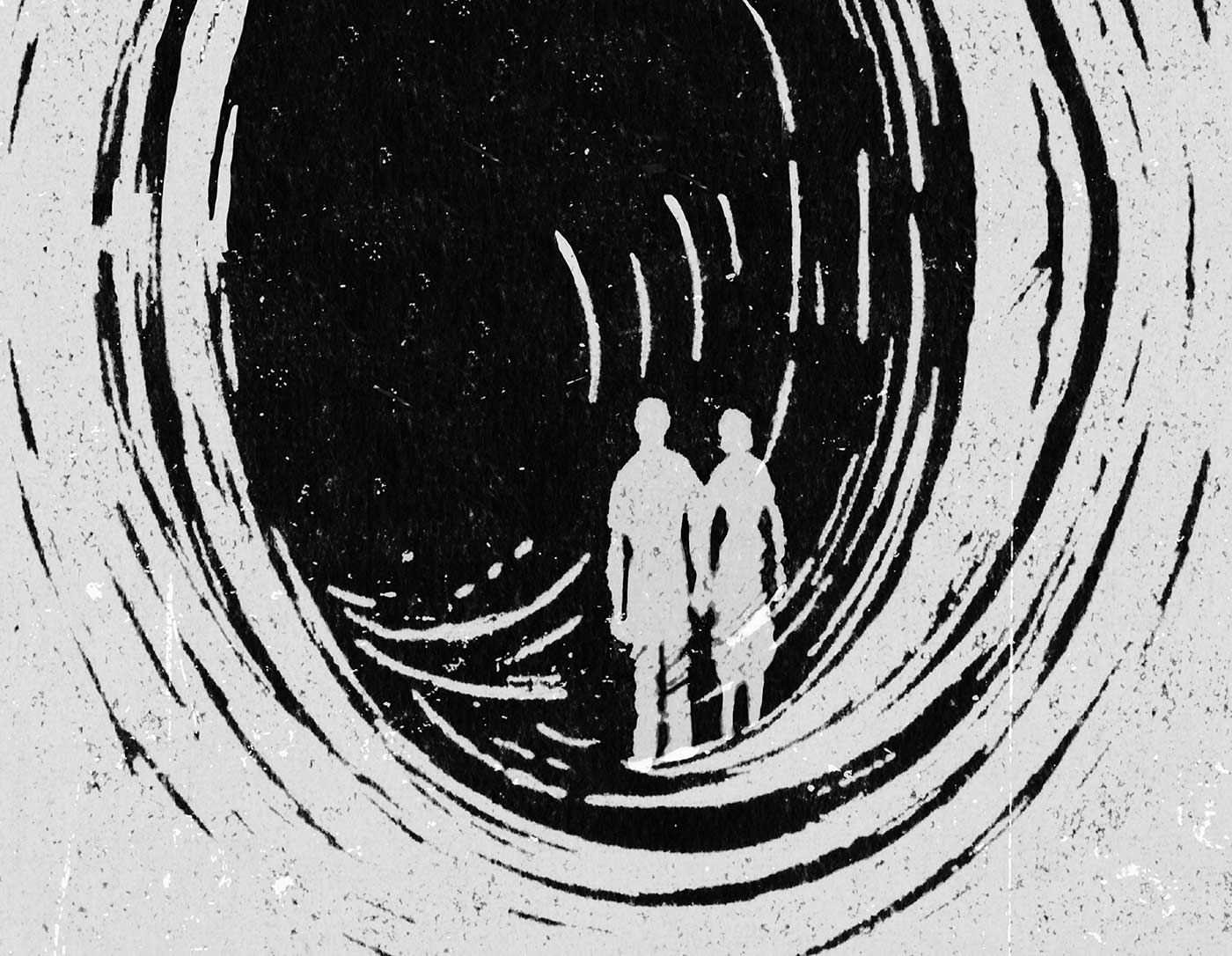

As I was working on my book Living in Wonder, an exorcist I know put me in touch with a young academic I call “Jonah.” Jonah had been deeply involved in demon--worship with a small cult, whose rituals also involved heavy use of psychedelic drugs. He left the cult and became a Christian. When I interviewed him, Jonah told me that what started him on a path to the occult was his teenage dissatisfaction with the bland suburban Evangelicalism in which he was raised. Neither the pastor nor anyone else in his congregation had answers for his questions. Once he arrived at college, he decided that Christianity had no answers. He began searching in alternative traditions. He told me, “I just kept following that deeper and deeper until I found demons at the center.”

Jonah told me that as an occultist, he often talked about enchantment as a way to draw in people who were exhausted by despair and meaninglessness. Christian enchantment, he now believes, is vital, because the currents of thought that have scoured and flushed away all sense of meaning from existence—“all the nihilism, the scientism, and relativism”—are not ends in themselves but the means by which demonic entities clear the ground to prepare people for what he calls “the religion of Antichrist.” “Once they feel that vacuum of meaninglessness,” he told me, “once they encounter that starvation for spiritual realities that truly exist, the enemy forces are ten miles ahead of us, in having this infrastructure prepared to pull people into things that seem benign but will eventually be revealed as gateways to hell itself.”

An exorcist in Rome told me that when people call on demons, even if they don’t fully realize what they are doing, the demons will come. But they come as slavers. That’s not how God works. But if we Christians don’t offer disenchanted and disoriented young people something more powerful than mere Bible study and moral living, we are going to keep losing them to the false enchantment of the dark side.

It’s Happening, Whether We Want It or Not

A friend in Texas recently sent me an image of an altar dedicated to Santa Muerte—Saint Death—a demonic counterfeit of the Virgin Mary that arose out of the ritual lives of Mexican drug cartels. The Santa Muerte cult is now widespread in Mexico. But my friend did not find this image in the barrios of Mexico City or rural Oaxaca but in a popular flea market in a small Texas city, where it is marketed as a “community altar.” He said his Mexican-American colleagues tell him this form of occultism is spreading like wildfire in their communities. You can even buy Santa Muerte effigies at Walmart. Already a decade ago, an American academic who studies religion said the Santa Muerte cult was the fastest-growing religion in the country.

NBC interviewed a gay Anglo man in New Orleans who identifies with Santa Muerte because he opposes the Christianity of his youth, which will not affirm his homosexuality. He built an altar to her in his front yard for the sake of spreading devotion. He said it attracts all kind of worshipers. It seems that the religious syncretism that has played a large part in Latin American life is now beginning to enter the American mainstream.

The New Orleans man said that he worships Santa Muerte because whenever you ask her for something, she delivers. As the Roman exorcist put it, when you call on the demons, they come. Christian Smith has told us that the moralistic therapeutic deists who think they are Christians believe that you really don’t have to talk to God unless you want something. It won’t take much to convince Americans who have developed an instrumentalist view of religion to turn to demonic gods who give them what they desire.

This is the difference between magic and true religion: magic is about the ritual manipulation of the spirit world to achieve certain results. True religion, at least for Christians, is instead about the worship of God to achieve harmony with him and his will, and to grow in love and virtue. The true God cannot be instrumentalized and bent to human will. Yet nominal Christians who think that he can be are especially vulnerable to rival forms of religion that foster this illusion. Many young people who grow up saturated in occult pop culture will understandably want the things they read about and see to come true in their own lives.

Religion scholar Tara Isabella Burton observes that paganism and its offshoots make sense for young adults because they appeal to their intuitional preferences (often called “lived experience”) and their rejection of institutions and established hierarchies as oppressive. Occultism promises an experience of the numinous, but unlike Christianity, in which believers surrender their wills to God, occultism tells practitioners that they can use higher powers to impose their own wills on the world.

What’s more, witchcraft and paganism typically track with progressive political commitments, especially feminism, environmentalism, and queer activism. That said, the growth of racism also sparks interest in forms of paganism that glorify racial consciousness and violence. How are we going to protect those we love from going down these paths if we don’t even know those paths are there, and why they appeal to the young while Christianity does not?

The False Enchantments of Technology

Elon Musk once tweeted: “Any sufficiently advanced magic is indistinguishable from technology.” He was making an inverted joke on a well-known aphorism from the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, who said that advanced technology looks for all the world like magic. Maybe Musk was just being cheeky, but his remark jolted me because the line between magic and technology is now starting to blur in bizarre ways not generally appreciated by the public.

Digital technology and the universality of online life in modern culture has created a new metaphysics among users. Because reality in the online world is highly elastic, those who are acculturated to that world are trained to think that their will should be unencumbered by limits—moral, material, or otherwise. It is no accident that the phenomenon of transgenderism emerged in the digital era and is so heavily focused on young people who grew up in the digital era and were formed by its standards. They expect material reality to conform to ideal digital reality and consider it an outrage if it does not.

Philosopher Antón Barba-Kay says that in the digital era, we face an enormous religious temptation. He says that “digital technology is a spiritual technology.” Why? Because “the digital era thus marks the point at which our concern will be mainly the control of human nature through our control of what we are aware of and how we attend to it.”

The temptation is to believe that we can exert control over human nature by merging ourselves with our own machines. This is what transhumanism is. The desire to merge human with machine is, says Barba-Kay, “most obviously a dream of total rational control, a desire to render ourselves and the world fully transparent to technical scrutiny. It is for this reason also, as I’ve said, a desire for a unified explanation of consciousness and matter.” He is saying here that the digital offers a counterfeit version of what Christianity calls the sacramental: the God-given metaphysical unity of spirit and matter. From a Christian point of view, this pseudo-sacramentality is a profound spiritual deception.

Digital life is the new Tower of Babel. Barba-Kay notes that digital technology is like a religion “in the sense that it now bears the full weight of our yearning for integration, participation, and incorporation in a larger purpose than our own.” The digital speaks to our desires and offers to fulfill them without any effort. The digital makes us into our own gods.

And the digital enchants. If one way to measure enchantment is by what commands a person’s attention, then smartphones are like having a crystal ball in one’s own pocket. Look at how closely children bond with smartphones if you doubt it (or, better, try taking one away from a child or teenager). Forget kids—think about adults. My smartphone is the last thing I look at before I go to bed and the first thing I see when I wake up. The embarrassing truth is that the “real world” for me, a writer and journalist, is as much the world that I enter through my smartphone and laptop as the one in which my body dwells.

One of the most shocking things I’ve learned is that some very senior people in Silicon Valley believe that artificial intelligence is a channel through which higher intelligences can communicate with us and guide our development. It sounds insane, but it’s happening. They think of this technology as a kind of advanced Ouija board.

Whether or not AI is a portal to the demonic, I have no idea. But even if not, that doesn’t mean it is without religious significance. In a pilot program in Florida, kids are being paired with AI entities that will theoretically be with them for their entire lives. The concept is that the AI will be a lifelong valet, learning about the child as he grows into adulthood and constantly hovering about him as a digital servant who knows its master better than the master knows himself. It’s hard to conceive of a more profound merging of man with machine than raising a child whose most intimate lifelong collaborator is an AI entity. The boundary between the self and the world would not only become porous; it would cease to exist. In what meaningful sense would that be different from spirit possession?

Along those lines, if AI becomes sentient, or so convincingly mimics sentience that it’s a distinction without a difference, then we will treat AI entities like gods. You think that’s silly? Human nature tells us otherwise.

In June 2024, Leopold Aschenbrenner, a top Silicon Valley AI scientist, published a long paper warning that AI is progressing toward “superintelligence” far faster than most people realize. By 2030, we will have built an AI network far more “intelligent” than humans. In the decade that follows, what Aschenbrenner calls a “new world order” will be born. He adds, chillingly, that “the alien species we’re summoning is one we cannot yet fully control.”

For all intents and purposes, these superintelligences will function like gods. The ground is being prepared now. We are all going to be living in that world, like the Hebrews during the Babylonian captivity. Only those with strong faith and strong metaphysical convictions will be able to detect the lie, and resist it.

The Strength to Suffer

Effective resistance by Christians to the coming deceptions and persecutions will require the ability to endure suffering. Indeed, Christians of the former Soviet bloc tell us that the most important skill in resisting totalitarianism was the ability to suffer for the truth. Strictly speaking, one doesn’t have to have a strong, active mystical sensitivity to be able to endure pain and deprivation for the sake of the faith—but it helps.

The Austrian Jewish psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl taught that a person who is convinced that life has deep meaning has the power to withstand great suffering. As an inmate digging a trench in a German concentration camp, Frankl tried to drive away the despair engulfing him by thinking of his faraway wife. He writes that in that moment, he suddenly

sensed my spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. I felt it transcend that hopeless, meaningless world, and from somewhere I heard a victorious “Yes” in answer to my question of the existence of an ultimate purpose. At that moment a light was lit in a distant farmhouse, which stood on the horizon as if painted there, in the midst of the miserable grey of a dawning morning in Bavaria. Et lux in tenebris lucet—and the light shineth in the darkness.

In that hierophany, that manifestation of the sacred, Dr. Frankl found the strength to go on that day. There are many other stories about angels, saints, even the Lord himself appearing to Christians in prison to encourage them. But we must not count on those things.

I once shared a meal in Budapest with Andrew and Norine Brunson. Andrew is an Evangelical missionary pastor who was imprisoned for many months by the Turks on trumped-up charges. In his memoir about his prison ordeal, Brunson writes of the excruciating dark night of the soul that overtook him. God had always seemed so near, but now, trapped in a Muslim prison, the Lord had withdrawn his presence, or so it seemed.

It broke Andrew Brunson, as he humbly confesses in the book. At our dinner, he told me he read the prison memoir of Dr. Silvester Krcmery, the Slovak underground church leader who endured a decade as a political prisoner of the Communists without breaking. Pastor Brunson was trying to figure out what he should have done prior to prison to make himself stronger. The answer, he found, was to have developed dedicated spiritual disciplines that would serve to keep the fact of God’s enchanting presence clear to him, even though he could not sense it noetically. As a minister, he had always sought these intense spiritual experiences of God’s nearness, but he hadn’t done anything with them.

I took him to mean that he hadn’t adopted spiritual disciplines and exercises to sediment into his bones what was revealed in those theophanies. This is what got

Dr. Krcmery through prison: doing the routine daily liturgies of prayer, worship, and introspection that kept his gaze fixed firmly on the Lord. Grounding ourselves in sacrificial commitment and exercising prayer and other spiritual disciplines are the main ways we keep the primal religious experience of awe in God’s presence fresh in our minds. In this way, we build bulwarks against the temptation to despair.

Recognizing the Comet

In sum, from a Christian point of view, enchantment is learning to perceive God’s world as it truly is. The material world is in a mysterious but real way interpenetrated by spirit. Everything has ultimate meaning. Miracles happen. Angels exist, and so do demons. There is far more going on in reality than we can perceive with our senses alone. Hence, Christian re-enchantment—learning to live in wonder—is a fundamental part of a negative world survival strategy.

Harvard professor Elaine Scarry has said that education is not really about transferring information from teacher to student. It’s truly about training students to be staring at the right corner of the sky when a comet blazes by. It’s the same with Christian enchantment. We can’t make it happen, but we can prepare ourselves to recognize the comet when it appears.

One night in Genoa, Italy, in 2018, an Italian artist named Luca Daum gave me an engraving called “The Temptation of St. Galgano” (see “Eyes Fixed” in

the September/October 2023 Touchstone for the full story). My book Living in Wonder is more or less 200 pages of footnotes to Daum’s image. It tells us that when we have the initial experience of God manifesting to us,

we must go on our knees and make a meaningful sacrifice to serve him. And we must stay in prayer to keep our attention fixed firmly on God. This gives us the strength to overcome the temptation to look away from heaven and down to the earth, where the Deceiver waits to ensnare us.

Rod Dreher is a contributing editor to Touchstone. He is a writer and blogger and the author of several books, including The Benedict Option (2017) and Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents (2020).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on conference talk from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor