Astonishing Teacher

Kevin Raedy on Why a Christ Without Miracles Is Safely Ignored

Several years ago, I found myself at a small social gathering of little consequence, one that I likely would not remember at all but for a single line uttered in conversation. The discussion had somehow turned to the subject of Christianity, and someone pronounced—with a subtle hint of deprecation in her voice—that the important thing is to focus on the teachings of Jesus, rather than concern oneself with the person of Jesus. Before anyone who found himself suitably provoked by that proclamation could formulate a reply, the conversation veered off in another direction, and so ended the evening's discourse on theology.

I have to confess that I'm never quite sure what one intends with that canard, as if the teachings of Jesus would retain any coherence should the person of Jesus be neatly parsed out and discarded. But more immediately, when people make this sort of claim, I tend to wonder how long it has been since they last cracked open a Bible. Do they know what Jesus says about marriage and divorce? Fornication and adultery? Lying, greed, lust, and envy? Judgment? Have they actually read the Sermon on the Mount—and if so, are they meeting their enemies for coffee and picking up the check?

Infused with Power

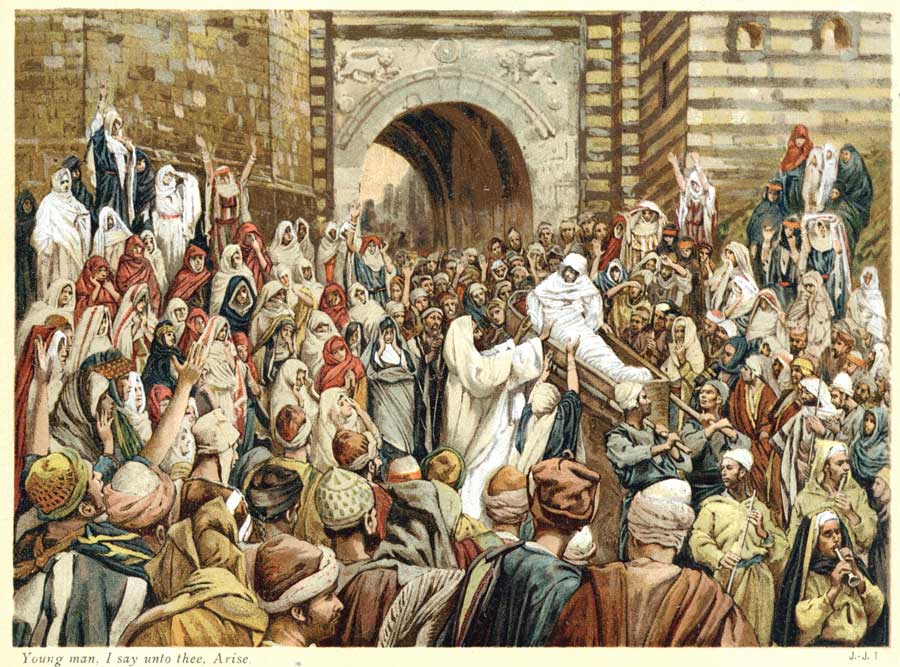

One obvious implication of this stance—that Jesus was a fine teacher, but it all ends there—is that the miracles attributed to him in the Bible never really happened. The feeding of the five thousand was not a literal multiplication of loaves and fishes; rather, it was the "miracle" of caring and sharing. The water turned to wine, the calming of the storm, the casting out of demons, the raising of Lazarus—let alone Jesus' virginal conception and Resurrection—these were all, at best, metaphors intended to lead us to a "spiritual truth," at worst, hagiographical myths concocted by admiring followers. When Thomas Jefferson took a razor to Scripture, excising all of the miracle stories from his Bible, it was this watered-down, demythologized, philosopher Jesus that he thought worth preserving.

But this sort of contrivance won't square with the biblical record itself, with the very texts that contain those teachings that the "great teacher" cohort claims to find so compelling. When the Bible tells us, in other words, that "the crowds were astonished at [Jesus'] teaching, for he taught them as one who had authority" (Matt. 7:28–29), it is a failure of interpretation to suppose that he spoke with excellent diction and a strong voice (although he may well have), strategically punctuating his key points with a fist to the lectern.

Rather, it means that against the backdrop of the Law and the prophets and the teaching of the scribes—all that was understood as the ancient and insuperable authority by which they lived their lives and worshiped God—Jesus was proclaiming something that was fundamentally new. His audience, those who actually heard his teaching firsthand, sensed the very presence and manifestation of authority on an order they had never encountered before; his words were infused with a power that could emanate only from the divine. From someone, in other words, with the capacity to perform miracles.

Willful Disbelief

Why does this matter?

In the sixteenth chapter of Luke's Gospel, Jesus tells the parable about an unnamed rich man and a poor man named Lazarus. The story is narrated as a back-and-forth between the rich man, who, having lived a life of luxury and extravagance, is now suffering the torments of hell, and Abraham, who is comforting Lazarus in heaven. The rich man asks Abraham to send Lazarus back to his surviving brothers with a message of warning, so that they might repent and avoid his own fate. "But Abraham said, 'They have Moses and the prophets; let them hear them.'" The rich man persists, and Abraham replies with finality, "If they do not hear Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead" (Luke 16:29,31).

Jesus was no doubt targeting the Pharisees here; he had been wrangling with them—over the love of wealth, no less—just before he told this parable. But I also take that final rejoinder to indicate that persistence in willful disbelief can cross a line such that even miracles lose their potency to convince, to bolster one's faith.

We see this elsewhere in the Bible. In the book of Exodus, an unrelenting procession of one calamitous plague after another isn't enough to sway a hardened Pharaoh. In Matthew's Gospel, Jesus casts out a demon, and some of the Pharisees attribute his power to Satan. In John's Gospel, the Pharisees refuse to accept that it was Jesus who gave sight to the man born blind. And the raising of Lazarus is, incredibly, not the eye-opener that prompts them to start rethinking their views on Jesus, but the breaking point that leads them to start plotting his death.

The Whole Fabric

Not a great deal has changed over two millennia when it comes to difficulties with the miracles of Christ; C. S. Lewis devoted an entire treatise to this subject. In Miracles, Lewis, apologist that he is, takes as truth the biblical account of Jesus' miracles and, brick by brick, lays the philosophical groundwork necessary for one to, at the very least, accept their plausibility. The narrow purpose he achieves functions as a cog within the larger Christian apologetic project. But along the way, Lewis occasionally reminds us of the overarching significance of miracles to the Christian narrative.

There are some, he says, who have no quarrel with the existence of a supernatural realm but cannot countenance the possibility of any sort of supernatural meddling in the affairs of the created order.

They therefore reject all forms of Supernaturalism which assert such interference and invasions: and specially the form called Christianity, for in it the Miracles, or at least some Miracles, are more closely bound up with the fabric of the whole belief than in any other. . . . you cannot [omit the miraculous] with Christianity. It is precisely the story of a great Miracle. A naturalistic Christianity leaves out all that is specifically Christian.

In a similar manner, he states that "we seldom find the Christian miracles denied except by those who have abandoned some part of the Christian doctrine. The mind which asks for a non-miraculous Christianity is a mind in process of relapsing from Christianity into mere 'religion.'"

Although it is not close enough to qualify as a paraphrase, I think it does no violence to Lewis's assertions to state that a Jesus who managed to attract large crowds with his teaching some 2,000 years ago in Palestine but who performed no miracles is not the Jesus of the Bible. (Or, to broaden the scope a bit, the god who cannot or does not bring about miracles today is not the Triune God of Christianity.) To deny the miracles of Jesus is to deny the person of Jesus. And a rejection of Jesus is a dismissal of Christianity.

The irony, of course, is that from such a vantage point, the idea of Jesus as merely a great teacher bears all the fruit of a cursed and withered fig tree. One can readily package the teaching of an ineffectual Jesus, who performed no miracles because he lacked the power to do so, as a stand-alone residual, as something left behind by a Jewish carpenter who got a little too big for his tunic. Left to our own devices, we will inevitably water down such teaching and contort it into whatever we, in our fallen state, want it to be. Which means that we'll render it—and by implication its source—inconsequential. In the end, a Jesus without miracles is a Jesus who can safely be ignored.

Divine Teacher

Since I began writing this piece, I have come across the results of two recently administered but entirely independent surveys, both of which indicate that a robust percentage of self-identifying Christians do not believe that Jesus is God. I know that isn't necessarily breaking news, but still—Christians. Where does one go from here?

Perhaps the wedding feast at Cana is a good place to begin, the site of Jesus' first miracle. The passage in John's Gospel that describes that occasion ends with this magnificent line: "This, the first of his signs, Jesus did at Cana in Galilee, and he manifested his glory; and his disciples believed in him" (John 2:11).

His disciples believed in him. Which is to say they believed in the person of Jesus, in the one who was filled with divine power, the power that could not be contained by death or sealed tomb. The very power that enabled him both to perform miracles and to astonish with words.

The Jesus who performs miracles cannot be ignored. And his teaching matters precisely and only because it comes from him.

Kevin Raedy holds MTS and ThM degrees and writes from Hillsborough, North Carolina, where he lives with his wife and two children. He has published in the journal Nova et Vetera and at Aleteia.org.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor