Mormon Vampires in the Garden of Eden

What the Bestselling Twilight Series Has in Store for Young Readers

by John Granger

If you have visited a bookstore, scanned the tabloids at a grocery store check-out, or watched Entertainment Tonight at the airport (no one I know admits to watching the show at home) any time in the last four years, you know something about Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight books. They continue to dominate best-seller lists more than a year after the finale was published, and the movies based on the stories, like the novels, are second only to J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series in popularity.

Having been dragged into the Twilight books much against my will, I was delighted to find that Mrs. Meyer is a wonderful storyteller, if no champion stylist, and that her popularity isn’t due to Harry Potter withdrawal so much as to the artistry and meaning of her own work. Though they feature vampires, the novels are not vampire genre pieces; they are a brilliant mélange of Young Adult romance, alchemical drama, superhero comic book, and international thriller. This kind of seamless double and triple coding is no small feat, but Mrs. Meyer pulls it off.

A Spiritual Need

I suggest that the Twilight series is something for thoughtful people to be aware of and to think seriously about, first, because of its remarkable hold on the imagination of American readers and movie-goers, but second, and more important, because of the reason these books are so popular: They meet a spiritual need. Mircea Eliade, in his book The Sacred and the Profane, suggests that popular entertainment, especially imaginative literature and film, serves a religious or mythic function in a secular culture. When God is driven to the periphery of the public square, the human spiritual capacity longs for exercise, and it often finds it in the “suspension of disbelief” and activity of the imagination that are available in novels and movies.

The books and films that satisfy this spiritual longing most profoundly are the ones that have religious content of some kind, sometimes any kind. Not just The Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia but also Harry Potter and The Matrix contain symbolism and religious notes that resonate with readers and moviegoers.

Which brings us to Twilight. These Gothic romances featuring atypical vampires and werewolf champions are allegories about the love relationship between God and Man. They are, in fact, a re-telling of the Garden of Eden drama—with a Mormon twist. Here, the Fall is a good thing, even the key to salvation and divinization, just as Joseph Smith, Jr., the Latter-day Saint prophet, said it was. Twilight conveys the appealing message that the surest means to God are sex and marriage.

The Twilight Story

For those who haven’t read the series, here are basic plot summaries to help you follow the discussion:

Twilight: The heroine, Bella Swan, moves from sunny Phoenix, Arizona, to live with her dad in perpetually overcast Forks, Washington, out on the Olympic Peninsula. At Forks High School she meets and falls in love with Edward Cullen, a pale, handsome stranger with a secret. It turns out that he’s a vampire (if nothing like Count Dracula), and it’s all he can do to keep from eating her alive despite his family’s determination to live on animal blood rather than by killing and draining human beings. James, a Tracker vampire with no such scruples, decides he wants to hunt Bella down for lunch. Edward and family save the day after Bella serves herself up to James sacrificially to save mom.

New Moon: Bella cuts her finger at her birthday party and Edward’s brother attacks. Gallant young man that Edward is, at well over 100 years old if forever a teenaged boy, he decides, after saving Bella from brother, that he and his family must leave for Bella’s own good. She is only rescued from her grief by a Native American friend, Jacob Black, who has a secret of his own: He and his Quileute tribe are werewolves (shape-shifters) who transform themselves to protect their reservation from vampires. Meanwhile, James’s mate, Victoria, is after Bella to avenge James’s death. Edward is told that Bella has committed suicide and on that false report tries to get the lead vampires in Italy, the Volturi, to kill him to end his grief. Bella gets to Italy in time to save him, and they survive a harrowing interview with the Volturi, who let them go on the condition that Bella become a vampire soon. Edward agrees to change Bella, but only on the condition that she marry him first.

Eclipse: Edward or Jacob? How is a girl to decide? But Bella’s bigger problem is just staying alive; Victoria won’t give up on her plan to revenge James’s death, and she creates wild, “newborn” vampires as an assault team to get past Bella’s protectors out in Forks. In the thriller finish, Edward saves the girl and kills Victoria, and Bella decides to marry him, though she loves Jacob, too. Jacob goes lupine and runs for the North Woods.

Breaking Dawn: A beautiful wedding, a honeymoon on a private island—and the conception of a vampire-human baby, whose delivery almost results in Bella’s death. Edward saves her by bringing her into vampiredom, but the Volturi, who have doubts about Baby Nessie’s true nature, turn out in force to destroy Edward, Bella, baby, and anyone else who gets in their way. After the Cullens assemble a host of international witnesses to testify that Nessie is harmless, the Volturi balk in the final Mountain Meadow showdown when they learn that there is a South American aborigine who shares Nessie’s genetic make-up. The end.

An Inspiring Dream

The novels were inspired by a dream Meyer had in 2003, which she describes as follows:

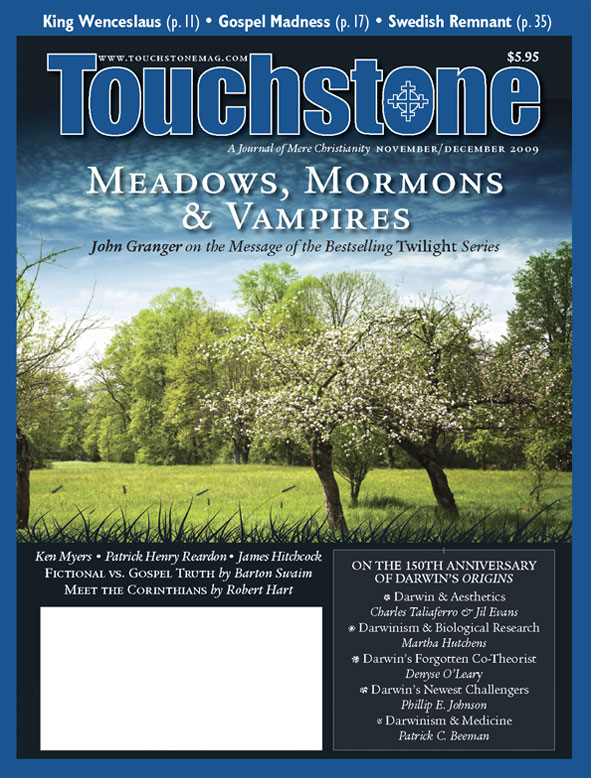

In my dream, two people were having an intense conversation in a meadow in the woods. One of these people was just your average girl. The other person was fantastically beautiful, sparkly, and a vampire. They were discussing the difficulties inherent in the facts that A) they were falling in love with each other while B) the vampire was particularly attracted to the scent of her blood, and was having a difficult time restraining himself from killing her immediately.

The key word in Mrs. Meyer’s dream is not “vampire” or “girlfriend” but “meadow.” The key confrontations in all four published Twilight books take place in meadows, usually a meadow in the Olympic Mountains. James the Tracker stumbles upon Bella there in Twilight, Victoria’s Newbie Vampires fight the Cullens there in Eclipse, and the epic final showdown with the Volturi in Breaking Dawn takes place there as well. Edward reveals himself to Bella in the “perfectly circular” meadow of Mrs. Meyer’s inspiring dream, and she sees Jacob Black, her Quileute buddy, as a werewolf for the first time in the same meadow in New Moon.

“Mountain Meadows,” however, means something much less pastoral and positive and much more visceral and painful to American Latter-day Saints (LDS). The summer of 2003 saw the publication of three books that focused on the 1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre, in which tragedy Mormon faithful in Southern Utah executed more than 120 men, women, and children on their way to California from Arkansas.

All three books paint the Mormon faith as inherently bloodthirsty, violent, secretive, and abusive to women and non-believers. The Twilight novels, especially Breaking Dawn, can be understood as a response to the challenge they posed to Mormon believers like Mrs. Meyer. In brief, Meyer was inspired to write works in which she addresses and resolves in archetypal story the criticisms being made of Mormonism by atheists and non-believing gentiles.

Heroic Cullens

For example, while most of Meyer’s vampires are dangerous—heartless, blood-atonement-driven religious believers who prey on non-believers—this is not true of the Cullen family, who are the Celestial-life Mormons of the story. (The Volturi, on the other hand, the ancient vampires in Italy who lead and police vampires everywhere, are a thinly disguised Roman Catholic Church, the “Whore of Babylon” to Joseph Smith, Jr., and his nineteenth-century followers.)

The Cullen family, unlike the other vampires, struggle to retain and perfect the humanity they lost in becoming immortals. In obedience to the “vision” of their Father, Carlisle Cullen, and the shared “conscience” of their family, they eat animal blood rather than human blood.

Carlisle Cullen was born in the mid-1660s, the same period when historic Mormonism was born in Europe. He became a vampire when he was bitten but not slain by a weakened vampire. His heroic choice to turn away from vampirism and to eat animal rather than human food turns his eyes golden rather than blood red. Over the next two centuries, he learns all he can about medicine and in the mid-1800s becomes a doctor, saving rather than taking human lives.

By placing the birth of the Cullen “vision” in the same time and place as the birth of Mormon beliefs (see Refiner’s Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1640–1844, by John L. Brooke) and by having Carlisle take up medical practice in the 1840s, the same time as Joseph Smith’s “restoration” of the gospel in America, Meyer indicates the allegorical—and apologetic—meaning of her story.

Inversions & Reversals

Indeed, I think that resolving her misgivings and interior conflicts as a Mormon woman in a land of non-Mormons was a major impetus of Mrs. Meyer’s writing. In her books, she lays out defenses, often as inversions or compensating reversals (such as one would find in dreams), for at least ten specific Mormon beliefs, practices, and historic events that most outsiders would see as evidence that Mormonism is a fraud and a cult. One example from each category will illustrate this point.

Belief: A core genealogical belief of Mormons is that Native Americans are the descendants of Abraham through the children of Lehi. But in several articles written in 2002 and 2003, LDS anthropologist Thomas W. Murphy has argued that DNA studies show “no intimate genetic link . . . between ancient Israelites and the indigenous peoples of the Americas—much less within the time frame suggested by the BoMor [Book of Mormon].”

Mrs. Meyer’s answer to this scientific challenge to her faith comes in the climax of Breaking Dawn. The Volturi have come to the Cullens’ Mountain Meadow for a showdown with the “vegetarians” and their allies, and it looks very bad for the latter. What saves them from the vampire-papists is an inversion of the genetics argument against the Book of Mormon revelation: The Cullens are saved by the ex machina appearance of a South American aborigine whose DNA proves that the Mormon vampires are telling the truth. Genetics isn’t the enemy; it’s the savior.

Practice: In his 2003 book, Under the Banner of Heaven, Jon Krakauer presents many damning anecdotes about the suffering of child-brides in communities of polygamous LDS fundamentalists who live, for the most part, above and outside the law in the Mormon belt. These girls are wed in their early teens to much older men practicing what they call “celestial marriage.”

When Bella meets Edward in January 2005, he is well over 100 years old, though he seems to be 17. Their relationship is hurried along because of Bella’s fear that, if she isn’t transformed into a vampire soon, she will become an unattractive old woman while he remains forever youthful. Edward, of course, says his love has nothing to do with age, but he also asserts that their marriage is a necessary condition for his making her a vampire. Since Bella’s whole life and her apotheosis depend on her fixed relationship with Edward, the real-life nightmare and crime of man-child marriage that Krakauer lays at the feet of Mormonism is re-packaged by Meyer as a child saving spiritual practice that the good guy insists upon.

Historic Event: The Mountain Meadows Massacre of 1857, cited above, is an atrocity with few equivalents in American history. The only Mormon defenses for it have been the pathetic insistence that the migrating families somehow provoked the attack and that all Utah was in a panic that they were about to be killed by the US Army and California militias gathering at their borders. Mrs. Meyer reflects this claim of religious persecution as justification for murderous “self-defense” in each of the Meadows confrontations in her books. Tellingly, the Meadows are the places where the Mormon-vampires are attacked, twice by invaders in great numbers, whom they only repel by heroic effort aided by something like miraculous intervention.

Some Critical Notes

Yet, for all the apologetic recasting of arguments non-Mormons make against her faith, Mrs. Meyer also incorporates substantial criticism of her church in her story. Most obviously, in depicting the Celestial Holy Family, i.e., the Cullens, as vampires, whatever their principles about killing humans, she seems to accept a large part of Krakauer’s assertion that Mormons are, by definition, violent, dangerous, and disrespectful of those different from the Saints.

Twilight is essentially an allegory of one gentile seeker’s coming to the fullness of Latter-day Saint faith and life. Bella, though, as Mrs. Meyer’s stand-in, is also a modern American woman who struggles with Edward’s patronizing misogyny and over-protectiveness. Her mind is the only one in the book not open to him, which serves both as an indication of her reverential reserve towards him as God or prophet and her resistance to being totally subject to him. Though devoted to and in love with him, she sounds notes throughout the series that reflect something like feminism.

Bella’s life works out happily ever after, but that of another character, Leah Clearwater, the lone female werewolf in the story, stands as a reminder of the isolation and emptiness experienced by an intelligent, gifted woman not tied to a man in this community of believers.

Mrs. Meyer also takes a poke or two at Joseph Smith, Jr., himself. Particularly telling here is the story of Rosalie Hale, a beautiful woman whom Carlisle Cullen turned into a vampire on her deathbed in 1933, half-hoping she would be a match for his “son,” Edward. In real life, “Hale” was the maiden name of Smith’s first wife, Emma, who did not accept the prophet’s “principle” of plural marriage.

Rosalie is the very beautiful daughter of an ambitious family in Rochester, New York, who becomes engaged to the most eligible bachelor in the city, the rich and flamboyant Royce King II. The city and name both translate to the Mormon prophet because American Mormonism was born just outside Rochester, the “2nd” is a transparency for “Jr.,” and, since roi is the French word for “king,” “Royce King” points to a man twice crowned. Smith was twice ordained king, first in 1843 and then as “King of the World” in 1844.

Rosalie never marries Royce because she is gang-raped and left for dead by drunken Royce and his friends (as a vampire, she has her revenge on them all). I think Mrs. Meyer’s opinion about the prophet’s “principle,” his treatment of his first wife, and that he deserved the death he received, in history and in her fiction, are well laid out in Rosalie’s story—an opinion well outside LDS orthodoxy, I don’t need to add.

Postmodern Pitch

But if most of Meyer’s readers are not Mormons and don’t share her concerns, why are millions of them so engaged with the Twilight books?

One reason can be summed up by the term “genre genius.” I have written that much of J. K. Rowling’s success in her Harry Potter series lay in her skillful blending of two literary types that, standing alone, were rather tired or played out: school-boy fiction a la Tom Brown’s Schooldays and gothic fiction of the Bram Stoker and Mary Shelley variety. Twilight displays a similar genre genius. The story types Meyer blends are Young Adult boy-meets-girl romance like The Fantastiks, Gothic romance grafted from the Brönte sisters, and the international-thriller blockbuster formula.

A second reason stems from Meyer’s blending of Mormon and post-modern morality. Not surprisingly, the sexual morality of the Twilight saga largely reflects LDS teaching about chastity and modesty. Edward and Bella are famous for sleeping together every night without “sleeping together” in the sexual sense of the expression.

But in other respects, Mrs. Meyer delivers the same postmodern mantras as just about every other author, screenwriter, and pundit of our times: Diversity is the core good, prejudice is the greatest evil, and the meta-narrative or core cultural myth on which you’ve been raised is what keeps you from seeing things as they are (“Don’t believe what you think!”). Free, informed Choice is the only means to escape these myths and “self-actualize.”

For example, vampires and werewolves aren’t at all what you’ve been told; the myths about them are all lies and distortions. Get past the fairy tales you’ve been taught and understand that the beings you’ve been taught to fear and hate (or just not believe in) are the only real people there are—and you’ll want to join them.

For a book with Mormon apologetic material and spiritual allegory, the postmodern pitch has a relatively pointed feel compared to, say, Harry Potter.

Allegories & Symbols

But perhaps the primary source of the appeal of the Twilight saga stems from the numerous allegorical and hermetic meanings that can be drawn from the narrative. Among the allegorical figures are those representing American patriots, Amazon feminists, Middle-Eastern Muslims, Celtic pagans, and even Orthodox Christians, who are represented by Romanian vampires who centuries ago were displaced by the Volturi.

The most powerful allegory, though, is Twilight’s re-telling of the Garden of Eden Genesis tale, a spiritual allegory of the God-and-man love story in a teen romance wrapper, about which I’ll explain more below.

The Twilight novels also contain numerous symbols and archetypal metaphors, among which the circle, alchemy, and logos epistemology are prominent.

Circles, for example, are a symbol of the transcendent being’s relationship with the visible. The center of the circle is invisible and unknowable but, mysteriously, it is only through the center, the defining point equidistant from all points of the circumference, that we know the shape is a circle. The first and most important of Mrs. Meyer’s circles is the perfectly circular meadow in which Edward reveals his true self to Bella, but circles are the repeated, almost default shape of key events in Twilight.

Allusions to alchemy, the traditional science featuring the three-stage transformation of lead to gold, represent human transformation from spiritual darkness (lead) to enlightenment (gold)—hence, the luminous golden eyes of the Cullen family.

A God & Man Love Story

But the predominant hermetic theme in Mrs. Meyer’s work is her understanding of “mind” as the fabric of reality and synonymous with the “knowledge of the heart” as opposed to the brain and cranial thought. Almost every page in New Moon, for example, mentions Bella’s chest pains, the emptiness of her heart, and her hollowness in Edward’s absence.

Edward himself is the story-cipher for the Christ or incarnate Logos who lives in the human “inner heart.” Though described many times as an “angel” and though he has many of the characteristics of Joseph Smith, Jr., he is also, as the First Son of the Cullen Father and Bella’s means to joining this Holy Family, the Christ figure of the story. His signature ability to enter into all minds (even Bella’s in the end) indicates his identity as the Logos that is the pre-existent “cohesion of all things” (Col. 1:17).

Bella, as an allegorical Everyman and earnest, self-sacrificing spiritual seeker, is defined by her relationship with this Word, whom she knows in her heart. She has left the city of the Sun (Phoenix) to walk into the Forest of Forks in Dante’s footsteps. What she finds in the dream meadow is a “sparkly” vampire, i.e., the Light of the World who sits motionless at the center of the meadow’s perfect circle. In that circle, Edward and Bella describe their love for each other.

Their romance, cosmically disproportionate, is a parable or transparency of the inequalities and responsibilities of the divine-human synergy. God, like Edward his Bella, cannot love man fully or he would destroy man’s free capacity to love and the virtue in his choice of obedience to God. Man, like Bella and her Edward, must die to his “flesh” identity of body and soul and risk all to love God truly. Edward’s “divine” love is constant, unchanging, and respectful. Bella’s human love is selfless and sacrificial. The saga is the story of her transformation in “Christ” consequent to her choosing the apple from his tray in the high-school cafeteria.

Twilight mania is largely a function of the reader’s identification with Bella, whose love and longing for union with Edward as Word or Christ enables the reader to transcend his individual concerns for an imaginative experience of something more real and lasting.

Thus we find, in this Harlequin edition of the Song of Songs, the God-Man love story that is the key to unlocking Twilight’s appeal. Eliade is right; in a secular culture, entertainments serve a religious function—and this most fundamental spiritual drama is as popular as it is because it smuggles in the core religious message of the Fall of man and his return to union with God through his Word.

A Good Fall

This brings us back to the Garden of Eden. As mentioned above, Twilight is a romantic retelling of the story of Man’s Fall presented in the engaging and exciting wrappers of a romance and an international thriller. This may sound like a stretch, but consider the first book’s cover—a woman’s arms holding out an apple—and its opening epigraph—“But the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not taste of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die” (Gen. 2:17).

This isn’t, however, the story as Moses told it or as Christian saints and sages have understood it. As a Mormon, Mrs. Meyer departs from the traditional Christian understanding of that event, and the nature of her departure appeals to rather than repels her readers.

Christians understand Adam and Eve’s disobedience to God, their “original sin,” or Fall, as the beginning of man’s distance from God, a distance that man could not restore on his own, but that required the incarnation and sacrifice of a divine, sinless Savior to accomplish.

Mormons reject this interpretation. Not only do they hold the Pelagian view that human conscience and free will are sufficient for salvation, but they go a step further, asserting that, not only was the Fall not a bad thing, it was actually a good, even necessary thing for human salvation.

In some streams of Mormon tradition, Adam is, in fact, the finite God of earth (or the Archangel Michael), and Eve is his celestial wife from another planet. The Fall and expulsion from Paradise, according to this view, were necessary in order for Adam and Eve to marry and reproduce. “Celestial marriage” is a core ordinance for Mormon exaltation (salvation), and without the “Fall,” man could not take this important step in his progression from mortality to post-mortal life as a god in the Celestial Kingdom.

This is a remarkable departure from orthodox, creedal Christianity with respect to sexuality and understanding how human beings relate to God. In traditional Christianity, sexual continence is adopted by those who aspire to devote themselves more deeply to the things of God, while in Mormonism, sex within marriage is itself an edifying, even salvific, spiritual exercise. A “single Mormon” is something like a “square circle,” and monastic vocation a sacrilege.

Joseph Smith, Jr.’s doctrines of Eternal Progression and the sufficiency of human will and conscience also break with Christian tradition. Instead of man working in synergy with God to receive and be transformed by his grace, Mormonism advocates a can-do spirit of works, which, if performed in conformity with God’s teachings in the LDS church, will result in one’s drawing ever nearer to God in this life and in the next.

Spiritual Entertainment

What does this have to do with why readers love Twilight?

In a nutshell, Bella is Eve and Edward is the Adam-God of Mormon theology. Their “Fall”—when Bella/Eve/Man chooses the apple from the tray of Edward/Adam/God, although rife with dangers and difficulties, is the beginning of a spiritual transformation culminated by an alchemical wedding with the God-Man. The story is a romantic allegory depicting the roles and responsibilities of the divine and human lovers, but it has the specifically Mormon hermetic twist that sex within marriage is the endgame and the only means to personal salvation and immortal life.

Mrs. Meyer’s books are as popular as they are because, like the LDS beliefs that are the substance of her meaning, they reflect and reinforce conventional thinking regarding sexuality more than they challenge it (even if Edward’s self-control and his insistence on chastity before marriage are very hard for many readers to understand). Furthermore, the anagogical meaning and spirituality of Twilight betoken that union with God, aptly enough in a romance, is largely about physical congress.

Eliade was right in saying that we are consumed by our entertainments because they satisfy our longing for some kind of spiritual experience, even if only imaginative, in a world that denies there is a God and elides the psychic and noumenal realms into the single category of “delusion.” People are drawn to, and many are consumed by, those books and movies that most engagingly and convincingly deliver or smuggle in this religious content and mythic meaning. Not surprisingly, though, this meaning cannot tear down or even challenge the golden calves of our modern moral landscape.

Twilight fits this bill superbly. It is much better writing and a much more profound reading experience than its critics allow. It is also a confirmation in story of the conventional but anti-traditional American beliefs that inform Latter-day Saint teaching. Mothers not wanting their daughters to grow up to be Mormons (or, worse, licentious individualists) might need to be concerned more for the weight and content of Mrs. Meyer’s Pelagian symbolism and meaning than about the bad example of Edward chastely watching over Bella every night.

John Granger is an Orthodox Reader and the author of several books about Harry Potter, including How Harry Cast His Spell (SaltRiver, 2008) and The Deathly Hallows Lectures (Zossima Press, 2008). His website is HogwartsProfessor.com.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor